Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate (pronounced /ˈpɔnʧəs ˈpaɪlət/; Latin: Pontius Pilatus, Greek: Πόντιος Πιλᾶτος) was the Prefect of the Roman Judaea province from the year AD 26 until AD 36. He is typically known as the sixth Procurator of Judea, but some sources cite him as the fifth. He is best known as the man who was the judge at the trial of Jesus and ordered his crucifixion.

Pilate appears in all four canonical Christian Gospels. Mark, demonstrating Jesus to be innocent of plotting against Rome, portrays Pilate as extremely reluctant to execute Jesus, blaming the Jewish hierarchy for his death, even though he was the sole authority for this action.[1] In Matthew, Pilate washes his hands of Jesus and reluctantly sends him to his death.[1] In Luke, Pilate not only agrees that Jesus did not conspire against Rome, but Herod, the tetrarch, also finds nothing treasonous in Jesus' actions.[1] In John, Jesus makes no claim to be the Son of Man or the Messiah to Pilate or to the Sanhedrin.[1]

Pilate's biographical details before and after his appointment to Judaea are unknown, but have been supplied by tradition, which include the detail that his wife's name was Claudia (she is canonized as a saint in the Greek Orthodox Church) and competing legends of his birthplace.

Contents[hide] |

Etymology of the name Pilatus

There are several possible origins for the cognomen Pilatus

A commonly accepted one is that it means "skilled with the javelin". The pilum (= javelin) was five feet of wooden shaft and two feet of tapered iron. When the point penetrated a shield, the shaft would bend and hang down, thus rendering it impossible to throw back. [2]

Another possible origin of the cognomen Pilatus was the name given to a hat worn by the devotees of the Dioskouroi. The Castorian cult was well established throughout the empire and persisted will into the 5th Century AD particularly among the Dacian and Sarmatian soldiers throughout the frontiers of the empire. The name Pileatus was used as a cognomen by the descendants of Burebista of Dacia whose decendants are known to have been soldiers who were stationed in Judea, Britain, Spain, Gaul, and Germany.

Birthplace

Pilate's date and place of birth are unknown. Fortingall in Perthshire, Scotland[3]; Tarraco (now Tarragona) in Spain, and Forchheim and its suburb Hausen in Germany have all developed local legends. The author of the Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911 article noted that Pontius suggested a Samnite origin—among the Pontii—and his cognomen Pileatus, if it derived from the pileus or cap of liberty, descent from a freedman. He is commonly believed to be descended from Gaius Pontius, a Samnite General. [4] The theory of Pilate having his origins in Scotland is not so unlikely. There is a family legend/story among the ancient MacLabhrain Clan of Balquidder (the modern MacLarens) which states that Pilate's father did indeed live in Perthshire and did have a union with a woman of the clan. The product of this 'marriage' was a child who came to be known as Pontius Pilate. Thus many contemporary MacLarens do claim a blood relationship with Pilate.

Titles and duties

Pontius Pilate's title was traditionally thought to have been procurator, since Tacitus speaks of him as such. However, an inscription on a limestone block known as the Pilate Stone — apparently a dedication to Tiberius Caesar Augustus — that was discovered in 1961 in the ruins of an amphitheater at Caesarea Maritima refers to Pilate as "Prefect of Judaea".

The title used by the governors of the region varied over the period of the New Testament. When Samaria, Judea proper and Idumea were first amalgamated into the Roman Judaea Province,[5] from 6 to the outbreak of the First Jewish Revolt in 66, officials of the Equestrian order (the lower rank of governors) governed. They held the Roman title of prefect until Herod Agrippa I was named King of the Jews by Claudius. After Herod Agrippa's death in 44, when Iudaea reverted to direct Roman rule, the governor held the title procurator. When applied to governors, this term procurator, otherwise used for financial officers, connotes no difference in rank or function from the title known as prefect. Contemporary archaeological finds and documents such as the Pilate Inscription from Caesarea attest to the governor's more accurate official title only for the period 6 through 44: prefect. The logical conclusion is that texts that identify Pilate as procurator are more likely following Tacitus or are unaware of the pre-44 practice.

The procurators' and prefects' primary functions were military, but as representatives of the empire they were responsible for the collection of imperial taxes,[6] and also had limited judicial functions. Other civil administration lay in the hands of local government: the municipal councils or ethnic governments such as — in the district of Judea and Jerusalem — the Sanhedrin and its president the High Priest. But the power of appointment of the High Priest resided in the Roman legate of Syria or the prefect of Iudaea in Pilate's day and until 41. For example, Caiaphas was appointed High Priest of Herod's Temple by Prefect Valerius Gratus and deposed by Syrian Legate Lucius Vitellius. After that time and until 66, the Jewish client kings exercised this privilege. Normally, Pilate resided in Caesarea but traveled throughout the province, especially to Jerusalem, in the course of performing his duties. During the Passover, a festival of deep national as well as religious significance for the Jews, Pilate, as governor or prefect, would have been expected to be in Jerusalem to keep order. He would not ordinarily be visible to the throngs of worshippers because of the Jewish people's deep sensitivity to their status as a Roman province.

Equestrians such as Pilate could not command legionary forces, and so in military situations, he would have to yield to his superior, the legate of Syria, who would descend into Palestine with his legions as necessary. As governor of Iudaea, Pilate would have small auxiliary forces of locally recruited soldiers stationed regularly in Caesarea and Jerusalem, such as the Antonia Fortress, and temporarily anywhere else that might require a military presence. The total number of soldiers at his disposal numbered in the range of 3000.[7]

The "Pilate Inscription" or "Pilate Stone" from Caesarea

The first physical evidence relating to Pilate was discovered in 1961, when a block of limestone was found in the Roman theatre at Caesarea Maritima, the capital of the province of Iudaea, bearing a damaged dedication by Pilate of a Tiberieum.[8] This dedication states that he was [...]ECTVS IUDA[...] (usually read as praefectus iudaeae), that is, prefect/governor of Iudaea. The early governors of Iudaea were of prefect rank, the later were of procurator rank, beginning with Cuspius Fadus in 44.

The inscription is currently housed in the Israel Museum in Jerusalem, where its Inventory number is AE 1963 no. 104. Dated to 26–37, it was discovered in Caesarea (Israel) by a group led by Antonio Frova.

Pilate in the canonical Gospel accounts

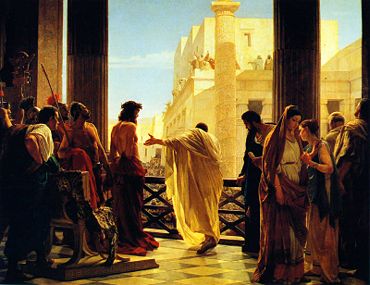

According to the canonical Christian Gospels, Pilate presided at the trial of Jesus and, despite stating that he personally found him not guilty of a crime meriting death, handed him over to crucifixion. Pilate is thus a pivotal character in the New Testament accounts of Jesus.

According to the New Testament, Jesus was brought to Pilate by the Sanhedrin, who had arrested Jesus and questioned him themselves. The Sanhedrin had, according to the Gospels, only been given answers by Jesus that they considered blasphemous pursuant to Mosaic law, which was unlikely to be deemed a capital offense by Pilate interpreting Roman law. [1] The Gospel of Luke records that members of the Sanhedrin then took Jesus before Pilate where they accused him of sedition against Rome by opposing the payment of taxes to Caesar and calling himself a king. Fomenting tax resistance was a capital offense [2]. Pilate was responsible for imperial tax collections in Judea. Jesus had asked the tax collector Levi, at work in his tax booth in Capernaum, to quit his post. Jesus also appears to have influenced Zacchaeus, "a chief tax collector" in Jericho, which is in Pilate's tax jurisdiction, to resign. [3]. Pilate's main question to Jesus was whether he considered himself to be the King of the Jews, and thus a political threat. Mark in the NIV translation states: "Are you the king of the Jews?" asked Pilate. "It is as you say," Jesus replied.

Following the Roman custom, Pilate ordered a sign posted above Jesus on the cross stating "Jesus of Nazareth, The King of the Jews" to give public notice of the legal charge against him for his crucifixion. The chief priests protested that the public charge on the sign should read that Jesus claimed to be King of the Jews. Pilate refused to change the posted charge. This may have been to emphasize Rome's supremacy in crucifying a Jewish king but may also be because he crucified Jesus out of pressure from the Sanhedrin and wanted to show that his sympathies were with Jesus. [4]

The Gospel of Luke also reports that such questions were asked of Jesus, in Luke's case it being the priests that repeatedly accused him, though Luke states that Jesus remained silent to such inquisition, causing Pilate to hand Jesus over to the jurisdiction (Galilee) of Herod Antipas. Although initially excited with curiosity at meeting Jesus, about whom he had heard, Luke states that Herod ended up mocking Jesus and so sent him back to Pilate. This intermediate episode with Herod is not reported by the other Gospels, which appear to present a continuous and singular trial in front of Pilate.

Unlike the synoptic gospels, the Gospel of John states that Jesus said to Pilate that he is a king and "came into the world ... to bear witness to the truth; and all who are on the side of truth listen to my voice", to which Pilate famously replied, "What is truth?" (John )

The Synoptic Gospels and John then state that it had been a tradition of the Jews to release a prisoner at the time of the Passover. Pilate offers them the choice of an insurrectionist named Barabbas or Jesus, somewhat confusing because Barabbas had the full name Jesus Barabbas, and bar-Abbas means son of the father. The crowd may not have understood whose release they were asking for, and were particularly susceptible to suggestions from the Jewish leaders. The crowd states that they wish to save Barabbas.

Pilate agrees to condemn Jesus to crucifixion, after the charge is brought that Jesus is a threat to Roman occupation through his claim to the throne of King David as King of Israel in the royal line of David. The small crowd in Pilate's courtyard, according to the Synoptics, had been coached to shout against Jesus by the Pharisees and Sadducees. The Gospel of Matthew adds that before condemning Jesus to death, Pilate washes his hands with water in front of the crowd, saying, "I am innocent of this man's blood; you will see."

Responsibility for Jesus' death

In all New Testament accounts, Pilate hesitates to condemn Jesus, but changes his mind when the crowd insists and the Jewish leaders remind him that Jesus's claim to be king is a challenge to Roman authority. Roman magistrates had wide discretion in executing their tasks, and some readers question whether Pilate would have been so captive to the demands of the crowd.[9]

With the Edict of Milan in AD 313, the state-sponsored persecution of Christians came to an end, and Christianity became officially tolerated as one of the religions of the Roman Empire. Afterward, in AD 325 the First Ecumenical Council at Nicaea promulgated a creed which was amended at the subsequent First Council of Constantinople in 381. The Nicene Creed incorporated for the first time the clause was crucified under Pontius Pilate (which had already been long established in the Old Roman Symbol, an ancient form of the Apostles' Creed dating as far back as the 2nd century AD) in a creed that was intended to be authoritative for all Christians in the Roman Empire.

Pilate in the Apocrypha

Little enough is known about Pilate, but mythology has filled the gap. A body of fiction built up around the dramatic figure of Pontius Pilate, about whom the Christian faithful hungered to learn more than the canonical Gospels revealed. Eusebius (Historia Ecclesiae ii: 7) quotes some early apocryphal accounts that he does not name, which already relate that Pilate fell under misfortunes in the reign of Caligula (AD 37–41), was exiled to Gaul and eventually committed suicide there in Vienne.

Other details come from less respectable sources. His body, says the Mors Pilati ("Death of Pilate"), was thrown first into the Tiber, but the waters were so disturbed by evil spirits that the body was taken to Vienne and sunk in the Rhône: a monument at Vienne, called Pilate's tomb, is still to be seen. As the waters of the Rhone likewise rejected Pilate's corpse, it was again removed and sunk in the lake at Lausanne. The sequence was a simple way to harmonise conflicting local traditions.

The corpse's final disposition was in a deep and lonely mountain tarn, which, according to later tradition, was on a mountain, still called Pilatus (actually pileatus or "cloud capped"), overlooking Lucerne. Every Good Friday, the body is said to reemerge from the waters and wash its hands.

There are many other legends about Pilate in the folklore of Germany, particularly about his birth, according to which Pilate was born in the Franconian city of Forchheim or the small village of Hausen only 5 km away from it. His death was (unusually) dramatised in a medieval mystery play cycle from Cornwall, the Cornish Ordinalia.

Pilate's role in the events leading to the crucifixion lent themselves to melodrama, even tragedy, and Pilate often has a role in medieval mystery plays.

In the Eastern Orthodox Church, Claudia Procula is commemorated as a saint, but not Pilate, because in the Gospel accounts Claudia urged Pilate to have nothing to do with Jesus. In some Eastern Orthodox traditions, Pilate committed suicide out of remorse for having sentenced Jesus to death.

Gospel of Peter

The fragmentary apocryphal Gospel of Peter exonerates Pilate of responsibility for the crucifixion of Jesus, placing it instead on Herod and the Jews, who unlike Pilate refuse to "wash their hands". After the soldiers see three men and a cross miraculously walking out of the tomb they report to Pilate who reiterates his innocence: "I am pure from the blood of the Son of God". He then commands the soldiers not to tell anyone what they have seen so that they would not "fall into the hands of the people of the Jews and be stoned".

Acts of Pilate

The 4th century apocryphal text that is called the Acts of Pilate presents itself in a preface (missing in some MSS) as derived from the official acts preserved in the praetorium at Jerusalem. Though the alleged Hebrew original of the document is attributed to Nicodemus, the title Gospel of Nicodemus for this fictional account only appeared in mediaeval times, after the document had been substantially elaborated. Nothing in the text suggests that it is in fact a translation from Hebrew or Aramaic.

This text gained wide credit in the Middle Ages, and has considerably affected the legends surrounding the events of the crucifixion, which, taken together, are called the Passion. Its popularity is attested by the number of languages in which it exists, each of these being represented by two or more variant "editions": Greek (the original), Coptic, Armenian and Latin versions. The Latin versions were printed several times in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

One class of the Latin manuscripts contain as an appendix or continuation, the Cura Sanitatis Tiberii, the oldest form of the Veronica legend.

The Acts of Pilate consist of three sections, whose styles reveal three authors, writing at three different times.

- The first section (1–11) contains a fanciful and dramatic circumstantial account of the trial of Jesus, based upon Luke 23.

- The second part (12–16) regards the Resurrection.

- An appendix, detailing the Descensus ad Infernos was added to the Greek text. This legend of a Harrowing of Hell has chiefly flourished in Latin, and was translated into many European versions. It doesn't exist in the eastern versions, Syriac and Armenian, that derive directly from Greek versions. In it, Leucius and Charinus, the two souls raised from the dead after the Crucifixion, relate to the Sanhedrin the circumstances of Christ's descent to Limbo. (Leucius Charinus is the traditional name to which many late apocryphal Acta of Apostles is attached.)

Eusebius (325), although he mentions an Acta Pilati that had been referred to by Justin and Tertullian and other pseudo-Acts of this kind, shows no acquaintance with this work. Almost surely it is of later origin, and scholars agree in assigning it to the middle of the 4th century. Epiphanius refers to an Acta Pilati similar to this, as early as 376, but there are indications that the current Greek text, the earliest extant form, is a revision of an earlier one.

Justin the Martyr - The First and Second Apology of Justin Chapter 35-"And that these things did happen, you can ascertain from the Acts of Pontius Pilate."

The Apology letters were written and addressed by name to the Roman Emperor Pius and the Roman Governor Urbicus. All three of these men lived between AD 138-161.

Minor Pilate literature

There is a pseudepigrapha letter reporting on the crucifixion, purporting to have been sent by Pontius Pilate to the Emperor Claudius, embodied in the pseudepigrapha known as the Acts of Peter and Paul, of which the Catholic Encyclopedia states, "This composition is clearly apocryphal though unexpectedly brief and restrained." There is no internal relation between this feigned letter and the 4th-century Acts of Pilate (Acta Pilati).

This Epistle or Report of Pilate is also inserted into the Pseudo-Marcellus Passio sanctorum Petri et Pauli ("Passion of Saints Peter and Paul"). We thus have it in both Greek and Latin versions.

The Mors Pilati ("Death of Pilate") legend is a Latin tradition, thus treating Pilate as a monster, not a saint; it is attached usually to the more sympathetic Gospel of Nicodemus of Greek origin. The narrative of the Mors Pilati set of manuscripts is set in motion by an illness of Tiberius, who sends Volusanius to Judea to fetch the Christ for a cure. In Judea Pilate covers for the fact that Christ has been crucified, and asks for a delay. But Volusanius encounters Veronica who informs him of the truth but sends him back to Rome with her Veronica of Christ's face on her kerchief, which heals Tiberius. Tiberius then calls for Pontius Pilate, but when Pilate appears, he is wearing the seamless robe of the Christ and Tiberius' heart is softened, but only until Pilate is induced to doff the garment, whereupon he is treated to a ghastly execution. His body, when thrown into the Tiber, however, raises such storm demons that it is sent to Vienne (via gehennae) in France and thrown to the Rhone. That river's spirits reject it too, and the body is driven east into "Losania", where it is plunged in the bay of the lake near Lucerne, near Mont Pilatus — originally Mons Pileatus or "cloud-capped", as John Ruskin pointed out in Modern Painters — whence the uncorrupting corpse rises every Good Friday to sit on the bank and wash unavailing hands.

This version combined with anecdotes of Pilate's wicked early life were incorporated in Jacobus de Voragine's Golden Legend, which ensured a wide circulation for it in the later Middle Ages. Other legendary versions of Pilate death exist: Antoine de la Sale reported from a travel in central Italy on some local traditions asserting that after the death the body of Pontius Pilate was driven until a little lake near Vettore Peak (2478 m in Sibillini Mounts ) and plunged in. The lake, today, is still named Lago di Pilato.

In the Cornish cycle of mystery plays, the "death of Pilate" forms a dramatic scene in the Resurrexio Domini cycle. More of Pilate's fictional correspondence is found in the minor Pilate apocrypha, the Anaphora Pilati (Relation of Pilate), an Epistle of Herod to Pilate, and an Epistle of Pilate to Herod, spurious texts that are no older than the 5th centurey

Veneration

The Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo Church recognized Pilate as a saint in the sixth century, based on the account in the Acts of Pilate.[10]

When Pilate arrived back in Rome his wife had become an early Chistian. There was a Church at Pilate residence. There is no way that a Roman wife would be allowed to have a Church in his house without tacit approval of Pilate himself.

Pilate in later fiction

Plays and films dealing with life of Jesus Christ often include the character of Pontius Pilate due to the central role he played in the final days of Christ's life. Writers have found various reasons to make Pilate a main character and to fill in any unknown details of his life. Pilate has been portrayed in a number of different ways by various writers:

- A weak and harried bureaucrat

- A hard governor who ruled with an iron fist

- A man who clearly sees how the story of Jesus will affect human history

- A man who regrets his role in Jesus' death (to greater or lesser extents, depending on the work)

- A man who is oblivious to the significance of the Galilean he condemns to death

- Pilate appears in the Mystery Plays and Passion Plays, the most notable being in the Cornish cycle in which he is summoned to Rome by Tiberius and sentenced to death for killing Jesus, but owing to this crime cannot be contained by earth, sea or water and so immediately proceeds (body and soul, rather than just soul) to hell.

- In the Vestibule of Hell in Dante's Divine Comedy, a figure is seen "who made the great refusal". This is interpreted to be either Pontius Pilate or Pope Celestine V.

- Pontius Pilate is portrayed in the classic work of Mikhail Bulgakov, The Master and Margarita, as being ruthless, complex, and yet human. In this novel, he exemplifies the statement "Cowardice is the worst of vices", and thus serves as a model, in an allegorical interpretation of the work, of all the people who have "washed their hands" by silently or actively taking part in the crimes committed by Joseph Stalin.

- This novel inspired the song Sympathy for the Devil by The Rolling Stones'. The title of this song, and its lyrics, seem to be derived from Bulgakov's portrayal of the Devil. Pilate is referenced in the verse: "And I was around when Jesus Christ / had his moment of doubt and pain / made damn sure that Pilate / washed his hands, and sealed his fate".[5][6]

- The Master and Margarita and Pilate are also referred to in the Pearl Jam song Pilate, on the album Yield.

- Pilate appears in three stories in Karel Čapek's collection Apocryphal Tales. In "Pilate's Evening", the weary governor wonders why Jesus' friends and relatives did not come to try and save him, and wishes that they had. "Pilate's Creed" features a dialogue between Pilate and Joseph of Arimathea. Their argument reflects the conflict between sceptical humanism (Pilate's famous "What is truth?") and religious certainty (Joseph's reply, "The truth in which I believe"). "The Crucifixion" features a world-weary Pilate disgusted with the political machinations that led to Jesus' condemnation.

- In Roger Caillois' short novel Pontius Pilate (1961), Pilate is portrayed as a vacillating colonial administrator who, during the day after Jesus' arrest, receives advice from his wife, from Judas Iscariot and from a Chaldaean friend who has amassed an immense knowledge of the world's various religions. In the end, he is shown as "a man who despite every hindrance succeeded in being brave".

- In The Flame and the Wind, a novel by John Blackburn, the aged Pilate is wracked by guilt over Jesus' death and directs his heir to find out if Jesus was really the son of God.

- In the Anatole France short story The Procurator of Judea, Pilate has retired to Sicily to become a gentleman farmer. This story is an example of the "oblivious" interpretation of Pilate.

- The Dutch writer Simon Vestdijk's 1938 novel De nadagen van Pilatus (The Last Days of Pilate) presents an account of Pilate's life after the crucifixion.

- Ann Wroe's Pontius Pilate: The Biography of an Invented Man is an attempt to provide the obscure official with a biography suitable to the man who is so influential to the Christian story. **The Royal Shakespeare Company debuted a performance piece called The Pilate Workshop in the summer of 2004, which attempted to cast Wroe's research in the form of a mystery play.

- In Monty Python's Life of Brian, Pilate is shown as a foolish leader who has trouble pronouncing the letter "r". He is also unable to remember who is in his prisons, and seems to be easily offended, as in the scene where he feels his guards are "insulting" his friend Biggus Dickus.

- Pilate is mentioned in the theme song for Marvel Comics' Nextwave series in a list of enemies, along with a monster, a pirate, an electric emu, a giant sky-rat, and a midget Hitler.

- Retired California politician James R. Mills wrote a novel titled Gospel According to Pontius Pilate in 1978. Pilate is described as a routine, cynical politician whose primary concern is to keep the local population content and maintain social order, rather than particular sense of rightness.

- In the rock opera Jesus Christ Superstar, in the song "Trial Before Pilate", a sympathetic Pilate pleads with Jesus to speak to him, saying that he believes the accused has "done no wrong" but "ought to be locked up" for insanity. Receiving no answer from the silent Jesus, Pilate eventually grows exasperated and tells him, "Die if you want to, you misguided martyr."

- The Collection of Short Stories 'The Night Chicago Died' by Tom Wessex contains a Pilate story, entitled 'An Afternoon on Skull Hill', in which the author supposes that Gestas, one of the thieves crucified with Christ was in fact Pilate's illegitimate son.

References

The references to Pilate, outside the New Testament:

- Josephus, Antiquities of the Jews 18.35, 55-64, 85-89, 177; The Wars of the Jews 2.169-177;

- Philo, Legatio ad Gaium (Embassy to Gaius) 38;

- Tacitus, Annals 15.44.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Harris, Stephen L., Understanding the Bible. Palo Alto: Mayfield. 1985.

- ↑ Ann Wroe: Pilate

- ↑ Did You Know? - Fortingall Yew

- ↑ Ann Wroe: Pilate

- ↑ H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0674397312, page 246: "When Archelaus was deposed from the ethnarchy in 6 CE, Judea proper, Samaria and Idumea were converted into a Roman province under the name Iudaea."

- ↑ law.umkc.edu

- ↑ "Administrative and military organization of Roman Palestine". Retrieved on 2006-05-08.

- ↑ The word Tiberieum is otherwise unknown: some scholars speculate that it was some kind of structure, perhaps a temple, built to honor the emperor Tiberius.

- ↑ Miller, 49–50.

- ↑ Pontius Pilate from the Catholic Encyclopedia

External links

- Pilate in history; the Tiberieum dedication block

- The Administrative and Military Organization of Roman-occupied Palestine

- Pontius Pilate Texts and Jona Lendering's discussion of all sources

- fresh translation of texts and analysis of evidence by Mahlon H. Smith

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Pilate, Pontius

- Catholic Encyclopedia (1911): Pontius Pilate

- Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911: "Pontius pilate"

- The Hausen Legend of Pontius Pilate

- Brian Murdoch, "The Mors Pilati in the Cornish Resurrexio Domini

- Fictional Memoires of Pontius Pilate - at BBC Radio 4 by Douglas Hurd

- Pronunciation of Ecclesiastical Latin

|

Pontius Pilate

Roman Rulers of Judea

|

||

| Preceded by Valerius Gratus |

Prefect of Iudaea 26–36 |

Succeeded by Marcellus |

|

||