Orangutan

| Orangutans[1] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Type species | ||||||||||||||

| Pongo borneo Lacépède, 1799 (= Simia pygmaeus Linnaeus, 1760) |

||||||||||||||

Orangutan distribution

|

||||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||||

|

Pongo pygmaeus |

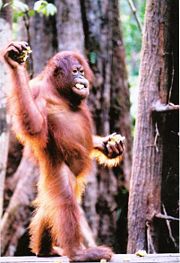

The orangutans are two species of great apes. Known for their intelligence, they live in trees and they are the largest living arboreal animal. They have longer arms than other great apes, and their hair is reddish-brown, instead of the brown or black hair typical of other great apes. Native to Indonesia and Malaysia, they are currently found only in rainforests on the islands of Borneo and Sumatra, though fossils have been found in Java, Vietnam and China. They are the only surviving species in the genus Pongo and the subfamily Ponginae (which also includes the extinct genera Gigantopithecus and Sivapithecus). Their name derives from the Malay and Indonesian phrase orang hutan, meaning "man of the forest".[2][3] The orangutan is an official state animal of Sabah in Malaysia.

Contents |

Etymology

The word orangutan (also written orang-utan, orang utan and orangutang) is derived from the Malay and Indonesian words orang meaning "person" and hutan meaning "forest",[4] thus "person of the forest". Orang Hutan is the common term in these two national languages, although local peoples may also refer to them by local languages. Maias and mawas are also used in Malay, but it is unclear if those words refer only to orangutans, or to all apes in general.

The word was first attested in English in 1691 in the form orang-outang, and variants with -ng instead of -n as in the Malay original are found in many languages. This spelling (and pronunciation) has remained in use in English up to the present, but has come to be regarded as incorrect by some.[5]

The name of the genus, Pongo, comes from a 16th century account by Andrew Battell, an English sailor held prisoner by the Portuguese in Angola, which describes two anthropoid "monsters" named Pongo and Engeco. It is now believed that he was describing gorillas, but in the late 18th century it was believed that all great apes were orangutans; hence Lacépède's use of Pongo for the genus.[6]

Ecology and appearance

Orangutans are the most arboreal of the great apes, spending nearly all of their time in the trees. Every night they fashion nests, in which they sleep, from branches and foliage. They are more solitary than the other apes, with males and females generally coming together only to mate. Mothers stay with their babies until the offspring reach an age of six or seven years. There is significant sexual dimorphism between females and males: females can grow to around 4 ft 2 in or 127 centimetres and weigh around 100 lbs or 45 kg, while flanged adult males can reach 5 ft 9 in or 175 centimetres in height and weigh over 260 lbs or 118 kg.[7]

The arms of an orangutan are twice as long as their legs. Much of the arm's length has to do with the length of the radius and the ulna rather than the humerus. Their fingers and toes are curved, allowing them to better grip onto branches. Orangutans have less restriction in the movements of their legs unlike humans and other primates, due to the lack of a hip joint ligament which keeps the femur held into the pelvis. Unlike gorillas and chimpanzees, orangutans are not true knuckle-walkers, and walk on the ground by shuffling on their palms with their fingers curved inwards.[8]

Bimodal male development

Adult male orangutans exhibit two modes of physical development, flanged and unflanged. Flanged adult males have a variety of secondary sexual characteristics, including cheek pads (called "flanges"), throat pouch, and long fur, that are absent from both adult females and from unflanged males. Flanged males establish and protect territories that do not overlap with other flanged males' territories. Adult females, juveniles, and unflanged males do not have established territories. A flanged male's mating strategy involves establishing and protecting a territory, advertising his presence, and waiting for receptive females to find him. Unflanged males are also able to reproduce; their mating strategy involving finding females in estrus and forcing copulation. Males appear to remain in the unflanged state until they are able to establish and defend a territory, at which point they can make the transition from unflanged to flanged within a few months.[9] The two reproductive strategies, referred to as "call-and-wait" for flanged male and "sneak-and-rape" for the unflanged male, were found to be approximately equally effective in one study group in Sumatra,[10] though this observation did occur during a period of instability in flanged male rank and unflanged male mating success may be lower in Borneo.[11]

Diet

Fruit makes up 65% of the orangutan diet. Fruits with sugary or fatty pulp are favored. Lowland Dipterocarp forests are preferred by orangutans because of their high fruit abundance, the same forests that provide excellent timber for the logging industry and good soil conditions for palm oil plantations. The fruit of fig trees are also commonly eaten since it is easy to both harvest and digest. Bornean orangutans are recorded to consume at least 317 different food items and include: young leaves, shoots, seeds and bark. Insects, honey and bird eggs are also included.[12] [13]

Orangutans are highly opportunistic foragers with the composition of their diet varying markedly from month to month.[14] Bark as a source of nourishment is only consumed as a last resort in times of food scarcity, fruits always being the preferred choice.

Orangutans are thought to be the sole fruit disperser for some plant species including the climber species Strychnos ignatii which contains the toxic alkaloid strychnine.[15] It does not appear to have any effect on orangutans except for excessive saliva production.

Geophagy, the practice of eating soil or rock, has been observed in orangutans. There are three main reasons for this dietary behavior; for the addition of minerals nutrients to their diet; for the ingestion of clay minerals that can absorb toxic substances; or to treat a disorder such as diarrhea. [16]

Orangutans use plants of the genus Commelina as an anti-inflammatory balm.[17]

Behaviour and language

Like the other great apes, orangutans are remarkably intelligent. Although tool use among chimpanzees was documented by Jane Goodall in the 1960s, it was not until the mid-1990s that one population of orangutans was found to use feeding tools regularly. A 2003 paper in the journal Science described the evidence for distinct orangutan cultures.[18]

According to recent research by the psychologist Robert Deaner and his colleagues, orangutans are the world's most intelligent animal other than humans, with higher learning and problem solving ability than chimpanzees, which were previously considered to have greater abilities. A study of orangutans by Carel van Schaik, a Dutch primatologist at Duke University, found them capable of tasks well beyond chimpanzees’ abilities — such as using leaves to make rain hats and leakproof roofs over their sleeping nests. He also found that, in some food-rich areas, the creatures had developed a complex culture in which adults would teach youngsters how to make tools and find food.[19]

A two year study of orangutan symbolic capability was conducted from 1973-1975 by Gary L. Shapiro with Aazk, a juvenile female orangutan at the Fresno City Zoo (now Chaffee Zoo) in Fresno, California. The study employed the techniques of David Premack who used plastic tokens to teach the chimpanzee, Sarah, linguistic skills. Shapiro continued to examine the linguistic and learning abilities of ex-captive orangutans in Tanjung Puting National Park, in Indonesian Borneo, between 1978 and 1980. During that time, Shapiro instructed ex-captive orangutans in the acquisition and use of signs following the techniques of R. Allen and Beatrix Gardner who taught the chimpanzee, Washoe, in the late-1960s. In the only signing study ever conducted in a great ape's natural environment, Shapiro home-reared Princess, a juvenile female who learned nearly 40 signs (according to the criteria of sign acquisition used by Francine Patterson with Koko, the gorilla) and trained Rinnie, a free-ranging adult female orangutan who learned nearly 30 signs over a two year period. For his dissertation study, Shapiro examined the factors influencing sign learning by four juvenile orangutans over a 15-month period.[20]

The first orangutan language study program, directed by Dr. Francine Neago, was listed by Encyclopedia Britannica in 1988. The Orangutan language project at the Smithsonian National Zoo in Washington, D.C., uses a computer system originally developed at UCLA by Neago in conjunction with IBM.[21] .

Zoo Atlanta has a touch screen computer where their two Sumatran Orangutans play games. Scientists hope that the data they collect from this will help researchers learn about socializing patterns, such as whether they mimic others or learn behavior from trial and error, and hope the data can point to new conservation strategies. [22]

Although orangutans are generally passive, aggression toward other orangutans is very common; they are solitary animals and can be fiercely territorial. Immature males will try to mate with any female, and may succeed in forcibly copulating with her if she is also immature and not strong enough to fend him off. Mature females easily fend off their immature suitors, preferring to mate with a mature male.

Orangutans have even shown laughter-like vocalizations in response to physical contact, such as wrestling, play chasing, or tickling.

Species

- Genus Pongo [1]

- Bornean Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus)

- Pongo pygmaeus pygmaeus - northwest populations

- Pongo pygmaeus morio - east populations

- Pongo pygmaeus wurmbii - southwest populations

- Sumatran Orangutan (P. abelii)

- Bornean Orangutan (Pongo pygmaeus)

The populations on the two islands were classified as subspecies until recently, when they were elevated to full specific level, and the three distinct populations on Borneo were elevated to subspecies. The population currently listed as P. p. wurmbii may be closer to the Sumatran Orangutan than the Bornean Orangutan. If confirmed, abelii would be a subspecies of P. wurmbii (Tiedeman, 1808).[23] Regardless, the type locality of pygmaeus has not been established beyond doubts, and may be from the population currently listed as wurmbii (in which case wurmbii would be a junior synonym of pygmaeus, while one of the names currently considered a junior synonym of pygmaeus would take precedence for the northwest Bornean taxon).[23] To further confuse, the name morio, as well as various junior synonyms that have been suggested,[1] have been considered likely to all be junior synonyms of the population listed as pygmaeus in the above, thus leaving the east Bornean populations unnamed.[23]

In addition, a fossil species, P. hooijeri, is known from Vietnam, and multiple fossil subspecies have been described from several parts of southeastern Asia. It is unclear if these belong to P. pygmaeus or P. abeli or, in fact, represent distinct species.

Conservation status

The Sumatran species is critically endangered[24] and the Bornean species of orangutans is endangered[25] according to the IUCN Red List of mammals, and both are listed on Appendix I of CITES. The total number of Bornean orangutans is estimated to be less than 14% of what it was in the recent past (from around 10,000 years ago until the middle of the twentieth century) and this sharp decline has occurred mostly over the past few decades due to human activities and development.[25] Species distribution is now highly patchy throughout Borneo: it is apparently absent or uncommon in the south-east of the island, as well as in the forests between the Rejang River in central Sarawak and the Padas River in western Sabah (including the Sultanate of Brunei).[25] The largest remaining population is found in the forest around the Sabangau River, but this environment is at risk[26]. A similar development have been observed for the Sumatran orangutans.[24]

The most recent estimate for the Sumatran Orangutan is around 7,300 individuals in the wild[24] while the Bornean Orangutan population is estimated at between 45,000 and 69,000.[25] These estimates were obtained between 2000 and 2003. Since recent trends are steeply down in most places due to logging and burning, it is forecast that the current numbers are below these figures.[25]

Orangutan habitat destruction due to logging, mining and forest fires, as well as fragmentation by roads, has been increasing rapidly in the last decade.[27][25][24] A major factor in that period of time has been the conversion of vast areas of tropical forest to oil palm plantations in response to international demand (the palm oil is used for cooking, cosmetics, mechanics, and more recently as source of biodiesel).[28][25][24] Some UN scientists believe that these plantations could lead to the extinction of the species by the year 2012. [29][30] Some of this activity is illegal, occurring in national parks that are officially off limits to loggers, miners and plantation development.[25][24] There is also a major problem with hunting[25][24] and illegal pet trade.[25][24] In early 2004 about 100 individuals of Bornean origin were confiscated in Thailand and 50 of them were returned to Kalimantan in 2006. Several hundred Bornean orangutan orphans who were confiscated by local authorities have been entrusted to different orphanages in both Malaysia and Indonesia. They are in the process of being rehabilitated into the wild.[25]

Major conservation centres in Indonesia include those at Tanjung Puting National Park and Sebangau National Park in Central Kalimantan, Kutai in East Kalimantan, Gunung Palung National Park in West Kalimantan, and Bukit Lawang in the Gunung Leuser National Park on the border of Aceh and North Sumatra. In Malaysia, conservation areas include Semenggoh Wildlife Centre in Sarawak and Matang Wildlife Centre also in Sarawak, and the Sepilok Orang Utan Sanctuary near Sandakan in Sabah.

See also

- Ah Meng – celebrity orangutan of the Singapore Zoo

- Ken Allen – famous escape artist at the San Diego Zoo

- Birutė Galdikas

- Chantek

- Human evolutionary genetics – more information on the speciation of humans and great apes

- Jeffrey H. Schwartz

- List of apes

- List of fictional apes

- Orangutans in popular culture

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Groves, C. (2005-11-16). Wilson, D. E., and Reeder, D. M. (eds). ed.. Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 183-184. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=12100803.

- ↑ "Orangutan Foundation International: All About Orangutans". Retrieved on 2006-08-01.

- ↑ "Tracking Orangutans from the Sky". PLoS Biol 3 (1): e22. 2004. doi:. http://biology.plosjournals.org/perlserv/?request=get-document&doi=10.1371/journal.pbio.0030022.

- ↑ "The Nation's Coolest Creatures". MSN. Retrieved on 2007-11-06.

- ↑ "Orangutan". alphadictionary.com. Retrieved on 2006-12-20.

- ↑ Groves, Colin (2002). "A history of gorilla taxonomy". Gorilla Biology: A Multidisciplinary Perspective, Andrea B. Taylor & Michele L. Goldsmith (editors) (Cambridge University Press) 3: 15–34. doi:. http://arts.anu.edu.au/grovco/Gorilla%20Biology.pdf.

- ↑ "Sumatran Orangutan Society". Retrieved on 2007-04-01.

- ↑ Schwartz, Jeffrey (1987). The Red Ape: Orangutans and Human Origins. pp. pp.286. ISBN 0813340640.

- ↑ "Orangutan". Primate Info Net. Retrieved on 2008-08-08.

- ↑ Harrison, Mark E. (2007). "The orang-utan mating system and the unflanged male: A product of increased food stress during the late Miocene and Pliocene?". Journal of Human Evolution 52 (3): 275. doi:.

- ↑ Goossens, B. (2006). "Philopatry and reproductive success in Bornean orang-utans (Pongo pygmaeus)". Molecular Ecology 15: 2577. doi:.

- ↑ Cawthon Lang KA (2005-06-13). "Primate Factsheets: Orangutan (Pongo) Taxonomy, Morphology, & Ecology". Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ↑ Galdikas, Birute M.F. (1988). "Orangutan Diet, Range, and Activity at Tanjung Puting, Central Borneo". International Journal of Primatology 9 (1).

- ↑ Galdikas, Birute M.F. (1988). "Orangutan Diet, Range, and Activity at Tanjung Puting, Central Borneo". International Journal of Primatology 9 (1).

- ↑ Rijksen, H. D. (December 1978). "A Field Study on Sumatran Orang Utans (Pongo pygmaeus abelii, Lesson 1827): Ecology, Behaviour and Conservation". The Quarterly Review of Biology 53 (4): 493. doi:. http://links.jstor.org/sici?sici=0033-5770(197812)53%3A4%3C493%3AAFSOSO%3E2.0.CO%3B2-4.

- ↑ "Science: Monkeys were the first doctors (Telegraph.co.uk)" (1 April 2008).

- ↑ Matt Walker Wild orangutans treat pain with natural anti-inflammatory New Scientist 28 July 2008

- ↑ "Roads through rainforest threaten our cultured cousins" (2003).

- ↑ Mongobay.com

- ↑ Dissertation

- ↑ "Orangutan Language Project". Think Tank Research Projects. Smithsonian National Zoological Park. Retrieved on 2006-12-20.

- ↑ Turner, Dorie (2007-04-12). "Orangutans play video games at GA. zoo". Retrieved on 2007-04-12.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 23.2 Bradon-Jones, D., A. A. Eudey, T. Geissmann, C. P. Groves, D. J. Melnick, J. C. Morales, M. Shekelle, and C. B. Stewart. 2004. Asian primate classification. International Journal of Primatology. 23: 97-164.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 Singleton, I.; Wich, S.A.; Griffiths, M. (2007), Pongo abelii. In: IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>, http://www.iucnredlist.org/search/details.php/39780/all, retrieved on 2008-04-02

- ↑ 25.00 25.01 25.02 25.03 25.04 25.05 25.06 25.07 25.08 25.09 25.10 Ancrenaz, M.; Marshall, A.; Goossens, B.; van Schaik, C.; Sugardjito, J.; Gumal, M.; Wich, S. (2007), Pongo pygmaeus. In: IUCN 2007. 2007 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. <www.iucnredlist.org>, http://www.iucnredlist.org/search/details.php/17975/all, retrieved on 2008-04-02

- ↑ Density and population estimate of gibbons (Hylobates albibarbis) in the Sabangau catchment, Central Kalimantan, Indonesia

- ↑ Rijksen, H.D. and Meijaard, E. (1999). Our Vanishing Relative: The Status of Wild Orang-utans at the Close of the Twentieth Century. Boston: Kluwer Academic Publishers.

- ↑ The oil for ape scandal

- ↑ Five years to save the orang utan | World | The Observer

- ↑ "The Last Stand of the Orangutan". United Nations Environment Programme (February, 2007). Retrieved on 2007-12-03.

External links

- Borneo Orangutan Survival International

- Information from Grungy Ape on the difference between the two Orangutan species

- Love for Orangutans

- Orangutan Appeal UK

- Orangutan Foundation International

- Orangutan Language Project

- Orangutan Outreach

- The Great Orangutan Project

- World's first eye cataract operation on an great male orangutan named Aman

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||