Polyethylene

Polyethylene or polythene (IUPAC name poly(ethene)) is a thermoplastic commodity heavily used in consumer products (notably the plastic shopping bag). Over 60 million tons of the material are produced worldwide every year.

Contents |

Description

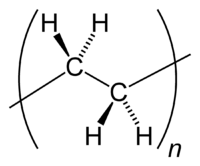

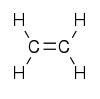

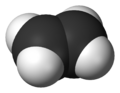

Polyethylene is a polymer consisting of long chains of the monomer ethylene (IUPAC name ethene). The recommended scientific name polyethene is systematically derived from the scientific name of the monomer.[1][2] In certain circumstances it is useful to use a structure–based nomenclature. In such cases IUPAC recommends poly(methylene).[2] The difference is due to the opening up of the monomer's double bond upon polymerisation.

In the polymer industry the name is sometimes shortened to PE in a manner similar to that by which other polymers like polypropylene and polystyrene are shortened to PP and PS respectively. In the United Kingdom the polymer is commonly called polythene, although this is not recognized scientifically.

The ethene molecule (known almost universally by its common name ethylene) C2H4 is CH2=CH2, Two CH2 groups connected by a double bond, thus:

Polyethylene contains the chemical elements carbon and hydrogen.

Polyethylene is created through polymerization of ethene. It can be produced through radical polymerization, anionic addition polymerization, ion coordination polymerization or cationic addition polymerization. This is because ethene does not have any substituent groups that influence the stability of the propagation head of the polymer. Each of these methods results in a different type of polyethylene.

Classification

Polyethylene is classified into several different categories based mostly on its density and branching. The mechanical properties of PE depend significantly on variables such as the extent and type of branching, the crystal structure and the molecular weight.

- Ultra high molecular weight polyethylene (UHMWPE)

- Ultra low molecular weight polyethylene (ULMWPE or PE-WAX)

- High molecular weight polyethylene (HMWPE)

- High density polyethylene (HDPE)

- High density cross-linked polyethylene (HDXLPE)

- Cross-linked polyethylene (PEX or XLPE)

- Medium density polyethylene (MDPE)

- Low density polyethylene (LDPE)

- Linear low density polyethylene (LLDPE)

- Very low density polyethylene (VLDPE)

UHMWPE is polyethylene with a molecular weight numbering in the millions, usually between 3.1 and 5.67 million. The high molecular weight results in less efficient packing of the chains into the crystal structure as evidenced by densities of less than high density polyethylene (for example, 0.930–0.935 g/cm3). The high molecular weight results in a very tough material. UHMWPE can be made through any catalyst technology, although Ziegler catalysts are most common. Because of its outstanding toughness and its cut, wear and excellent chemical resistance, UHMWPE is used in a wide diversity of applications. These include can and bottle handling machine parts, moving parts on weaving machines, bearings, gears, artificial joints, edge protection on ice rinks and butchers' chopping boards. It competes with Aramid in bulletproof vests, under the tradenames Spectra and Dyneema, and is commonly used for the construction of articular portions of implants used for hip and knee replacements.

HDPE is defined by a density of greater or equal to 0.941 g/cm3. HDPE has a low degree of branching and thus stronger intermolecular forces and tensile strength. HDPE can be produced by chromium/silica catalysts, Ziegler-Natta catalysts or metallocene catalysts. The lack of branching is ensured by an appropriate choice of catalyst (for example, chromium catalysts or Ziegler-Natta catalysts) and reaction conditions. HDPE is used in products and packaging such as milk jugs, detergent bottles, margarine tubs, garbage containers and water pipes.

PEX is a medium- to high-density polyethylene containing cross-link bonds introduced into the polymer structure, changing the thermoplast into an elastomer. The high-temperature properties of the polymer are improved, its flow is reduced and its chemical resistance is enhanced. PEX is used in some potable-water plumbing systems because tubes made of the material can be expanded to fit over a metal nipple and it will slowly return to its original shape, forming a permanent, water-tight, connection.

MDPE is defined by a density range of 0.926–0.940 g/cm3. MDPE can be produced by chromium/silica catalysts, Ziegler-Natta catalysts or metallocene catalysts. MDPE has good shock and drop resistance properties. It also is less notch sensitive than HDPE, stress cracking resistance is better than HDPE. MDPE is typically used in gas pipes and fittings, sacks, shrink film, packaging film, carrier bags and screw closures.

LLDPE is defined by a density range of 0.915–0.925 g/cm3. LLDPE is a substantially linear polymer with significant numbers of short branches, commonly made by copolymerization of ethylene with short-chain alpha-olefins (for example, 1-butene, 1-hexene and 1-octene). LLDPE has higher tensile strength than LDPE, it exhibits higher impact and puncture resistance than LDPE. Lower thickness (gauge) films can be blown, compared with LDPE, with better environmental stress cracking resistance but is not as easy to process. LLDPE is used in packaging, particularly film for bags and sheets. Lower thickness may be used compared to LDPE. Cable covering, toys, lids, buckets, containers and pipe. While other applications are available, LLDPE is used predominantly in film applications due to its toughness, flexibility and relative transparency.

LDPE is defined by a density range of 0.910–0.940 g/cm3. LDPE has a high degree of short and long chain branching, which means that the chains do not pack into the crystal structure as well. It has, therefore, less strong intermolecular forces as the instantaneous-dipole induced-dipole attraction is less. This results in a lower tensile strength and increased ductility. LDPE is created by free radical polymerization. The high degree of branching with long chains gives molten LDPE unique and desirable flow properties. LDPE is used for both rigid containers and plastic film applications such as plastic bags and film wrap.

VLDPE is defined by a density range of 0.880–0.915 g/cm3. VLDPE is a substantially linear polymer with high levels of short-chain branches, commonly made by copolymerization of ethylene with short-chain alpha-olefins (for example, 1-butene, 1-hexene and 1-octene). VLDPE is most commonly produced using metallocene catalysts due to the greater co-monomer incorporation exhibited by these catalysts. VLDPEs are used for hose and tubing, ice and frozen food bags, food packaging and stretch wrap as well as impact modifiers when blended with other polymers.

Recently much research activity has focused on the nature and distribution of long chain branches in polyethylene. In HDPE a relatively small number of these branches, perhaps 1 in 100 or 1,000 branches per backbone carbon, can significantly affect the rheological properties of the polymer.

Ethylene copolymers

In addition to copolymerization with alpha-olefins, ethylene can also be copolymerized with a wide range of other monomers and ionic composition that creates ionized free radicals. Common examples include vinyl acetate (the resulting product is ethylene-vinyl acetate copolymer, or EVA, widely used in athletic-shoe sole foams) and a variety of acrylates (applications include packaging and sporting goods).

History

Polyethylene was first synthesized by the German chemist Hans von Pechmann who prepared it by accident in 1898 while heating diazomethane. When his colleagues Eugen Bamberger and Friedrich Tschirner characterized the white, waxy, substance that he had created they recognized that it contained long -CH2- chains and termed it polymethylene.

The first industrially practical polyethylene synthesis was discovered (again by accident) in 1933 by Eric Fawcett and Reginald Gibson at the ICI works in Northwich, England.[3] Upon applying extremely high pressure (several hundred atmospheres) to a mixture of ethylene and benzaldehyde they again produced a white, waxy, material. Because the reaction had been initiated by trace oxygen contamination in their apparatus the experiment was, at first, difficult to reproduce. It was not until 1935 that another ICI chemist, Michael Perrin, developed this accident into a reproducible high-pressure synthesis for polyethylene that became the basis for industrial LDPE production beginning in 1939.

Subsequent landmarks in polyethylene synthesis have revolved around the development of several types of catalyst that promote ethylene polymerization at more mild temperatures and pressures. The first of these was a chromium trioxide-based catalyst discovered in 1951 by Robert Banks and J. Paul Hogan at Phillips Petroleum. In 1953 the German chemist Karl Ziegler developed a catalytic system based on titanium halides and organoaluminium compounds that worked at even milder conditions than the Phillips catalyst. The Phillips catalyst is less expensive and easier to work with, however, and both methods are used in industrial practice.

By the end of the 1950s both the Phillips- and Ziegler-type catalysts were being used for HDPE production. Phillips initially had difficulties producing a HDPE product of uniform quality and filled warehouses with off-specification plastic. However, financial ruin was unexpectedly averted in 1957 when the hula hoop, a toy consisting of a circular polyethylene tube, became a fad among youth in the United States.

A third type of catalytic system, one based on metallocenes, was discovered in 1976 in Germany by Walter Kaminsky and Hansjörg Sinn. The Ziegler and metallocene catalyst families have since proven to be very flexible at copolymerizing ethylene with other olefins and have become the basis for the wide range of polyethylene resins available today, including very low-density polyethylene and linear low-density polyethylene. Such resins, in the form of fibers like Dyneema, have (as of 2005) begun to replace aramids in many high-strength applications.

Until recently the metallocenes were the most active single-site catalysts for ethylene polymerisation known—new catalysts are typically compared to zirconocene dichloride. Much effort is currently being exerted on developing new, single-site (so-called post-metallocene) catalysts that may allow greater tuning of the polymer structure than is possible with metallocenes. Recently work by Fujita at the Mitsui corporation (amongst others) has demonstrated that certain salicylaldimine complexes of Group 4 metals show substantially higher activity than the metallocenes.

Physical properties

Depending on the crystallinity and molecular weight, a melting point and glass transition may or may not be observable. The temperature at which these occur varies strongly with the type of polyethylene. For common commercial grades of medium- and high-density polyethylene the melting point is typically in the range 120 to 130 °C ((250 to 265 °F). The melting point for average, commercial, low-density polyethylene is typically 105 to 115 °C (220 to 240 °F).

Most LDPE, MDPE and HDPE grades have excellent chemical resistance and do not dissolve at room temperature because of their crystallinity. Polyethylene (other than cross-linked polyethylene) usually can be dissolved at elevated temperatures in aromatic hydrocarbons such as toluene or xylene, or in chlorinated solvents such as trichloroethane or trichlorobenzene.

Environmental issues

The wide use of polyethylene makes it an important environmental issue. Though it can be recycled, most of the commercial polyethylene ends up in landfills and in the oceans (notably the Great Pacific Garbage Patch). Polyethylene is not considered biodegradable, as it takes several centuries until it is efficiently degraded. Recently (May 2008) Daniel Burd, a 16 year old Canadian, won the Canada-Wide Science Fair in Ottawa after discovering that Sphingomonas, a type of bacteria, can degrade over 40% of the weight of plastic bags in less than three months. The applicability of this finding is still a matter for the future.

Biopolyethylene

Braskem and Toyota Tsusho Corporation started Joint marketing activities for producing green polyethylene from sugar cane. Braskem will build a new facility at their existing industrial unit in Triunfo, RS, Brazil with an annual production capacity of 200,000 tons, and will produce High Density Polyethylene (HDPE) and Low Density Polyethylene (LDPE) from bioethanol derived from sugarcane [4].

References

- ↑ A Guide to IUPAC Nomenclature of Organic Compounds, Blackwell Scientific Publications, Oxford (1993).

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 J. KAHOVEC, R. B. FOX and K. HATADA; “Nomenclature of regular single-strand organic polymers (IUPAC Recommendations 2002);” Pure and Applied Chemistry; IUPAC; 2002; 74 (10): pp. 1921–1956.

- ↑ "Winnington history in the making". This is Cheshire. Retrieved on 2006-12-05.

- ↑ http://www.bioplastics24.com/content/view/1316/2/lang,en/

External links

- Polythene's story: The accidental birth of plastic bags

- Polythene Technical Properties & Applications

- Article describing the discovery of Sphingomonas as a biodegrader of plastic bags Kawawada, Karen, The Record (May 22 2008).

|

|||||

|

||||||||||||||||||