Polychaete

| Polychaetes Fossil range: Cambrian (or earlier?) - present |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

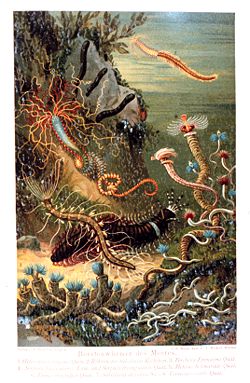

"A variety of marine worms": plate from Das Meer by M. J. Schleiden (1804–1881).

|

||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||

|

||||||

| Subclasses | ||||||

|

Palpata |

The Polychaeta or polychaetes are a class of annelid worms, generally marine. Each body segment has a pair of fleshy protrusions called parapodia that bear many bristles, called chaetae, which are made of chitin. Indeed the polychaetes are sometimes referred to as bristle worms. More than 10,000 species are described in this class. Common representatives include the lugworm (Arenicola marina) and the sandworm or clam worm Nereis.

Contents |

Anatomy and physiology

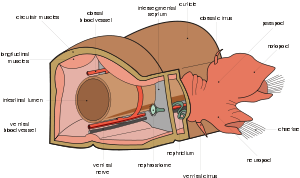

The polychaetes' paddle-like and highly vascularized parapodia are used for movement and act as the annelid's primary respiratory surfaces (parapodia can be thought of as kinds of external gills that are also used for locomotion). Polychaeta also have well-developed heads compared to other annelids. Their cuticle is constructed from cross-linked fibres of collagen, and may be 200nm to 13mm thick. their jaws are formed from scleritosed collagen, and their setae, scleritosed chitin.[1]

Ecology

Polychaetes are extremely variable in both form and lifestyle and include a few taxa that swim among the plankton. Most burrow or build tubes on the bottom, and some live as commensals. A few are parasitic. The mobile forms or Errantia tend to have well-developed sense organs and jaws, while the Sedentaria (or stationary forms) lack them but may have specialized gills or tentacles used for respiration and deposit or filter feeding, e.g., fanworms.

A few groups have evolved to live in terrestrial environments, like Namanereidinae with many terrestrial species, but are restricted to humid areas. Some have even evolved cutaneous invaginations for aerial gas exchange.

One notable polychaete, the Pompeii worm (Alvinella pompejana) is endemic to the hydrothermal vents of the Pacific Ocean. Pompeii worms are thought to be the most heat-tolerant complex animals known.

A recently discovered genus Osedax includes the Bone-eating snot flower.

Another remarkable polychaete is Hesiocaeca methanicola, which lives on methane clathrate deposits.

Lamellibrachia luymesi is a cold seep tube worm that reaches lengths of over 3 meters and may be the most long lived animal at over 250 years old.

Fossil record

The oldest crown group polychaetes fossils come from the Sirius Passet Lagerstatte, which is tentatively dated to the lower-middle Atdabanian (early Cambrian).[2] Many of the more famous Burgess Shale organisms, such as Canadia and Wiwaxia, may also have polychate affinites. An even older fossil, Cloudina, dates to the terminal Ediacaran period; this has been interpreted as an early polychaete, although consensus is absent.[3]

Being soft bodied, the fossil record of polychaetes is dominated by their fossilized jaws, known as scolecodonts, and the mineralized tubes that some of them secrete. However, their cuticle does have some preservation potential; it tends to survive for at least 30 days after a polychaete's death.[1] Although biomineralisation is usually necessary to preserve soft tissue after this time, the presence of polychaete muscle in the non-mineralised Burgess shale shows that this need not always be the case.[1] Their preservation potential is similar to that of jellyfish.[1]

Taxonomy and systematics

Taxonomically, the polychaetes are thought to be paraphyletic, meaning that as a group it contains its most recent common ancestor, but does not contain all the descendants of that ancestor. Groups that may be descended from the polychaetes include the earthworms, the leeches, sipunculans, and echiurans. The Pogonophora and Vestimentifera were once considered separate phyla, but are now classified in the polychaete family Siboglinidae.

Much of the classification below matches Rouse & Fauchald, 1998, although that paper does not apply ranks above family.

Older classifications recognize many more (sub)orders than the layout presented here. As comparatively few polychaete taxa have been subject to cladistic analysis, some groups which are usually considered invalid today may eventually be reinstated.

- Subclass Palpata

- Order Aciculata

- Basal or incertae sedis

- Family Aberrantidae

- Family Nerillidae

- Family Spintheridae

- Suborder Eunicida

- Family Amphinomidae

- Family Diurodrilidae

- Family Dorvilleidae

- Family Eunicidae

- Family Euphrosinidae

- Family Hartmaniellidae

- Family Histriobdellidae

- Family Lumbrineridae

- Family Oenonidae

- Family Onuphidae

- Suborder Phyllodocida

- Family Acoetidae

- Family Alciopidae

- Family Aphroditidae

- Family Chrysopetalidae

- Family Eulepethidae

- Family Glyceridae

- Family Goniadidae

- Family Hesionidae

- Family Ichthyotomidae

- Family Iospilidae

- Family Lacydoniidae

- Family Lopadorhynchidae

- Family Myzostomatidae

- Family Nautillienellidae

- Family Nephtyidae

- Family Nereididae

- Family Paralacydoniidae

- Family Pholoidae

- Family Phyllodocidae

- Family Pilargidae

- Family Pisionidae

- Family Polynoidae

- Family Pontodoridae

- Family Sigalionidae

- Family Sphaeodoridae

- Family Syllidae

- Family Typhloscolecidae

- Family Tomopteridae

- Basal or incertae sedis

- Order Canalipalpata

- Basal or incertae sedis

- Family Polygordiidae

- Family Protodrilidae

- Family Protodriloididae

- Family Saccocirridae

- Suborder Sabellida

- Family Oweniidae

- Family Siboglinidae (formerly the phyla Pogonophora & Vestimentifera)

- Family Serpulidae

- Family Sabellidae

- Family Sabellariidae

- Family Spirorbidae

- Suborder Spionida

- Family Apistobranchidae

- Family Chaetopteridae

- Family Longosomatidae

- Family Magelonidae

- Family Poecilochaetidae

- Family Spionidae

- Family Trochochaetidae

- Family Uncispionidae

- Suborder Terebellida

- Family Acrocirridae (sometimes placed in Spionida)

- Family Alvinellidae

- Family Ampharetidae

- Family Cirratulidae (sometimes placed in Spionida)

- Family Ctenodrilidae (sometimes own suborder Ctenodrilida)

- Family Fauveliopsidae (sometimes own suborder Fauveliopsida)

- Family Flabelligeridae (sometimes suborder Flabelligerida)

- Family Flotidae (sometimes included in Flabelligeridae)

- Family Pectinariidae

- Family Poeobiidae (sometimes own suborder Poeobiida or included in Flabelligerida)

- Family Sternaspidae (sometimes own suborder Sternaspida)

- Family Terebellidae

- Family Trichobranchidae

- Basal or incertae sedis

- Order Aciculata

- Subclass Scolecida

- Family Aeolosomatidae

- Family Arenicolidae

- Family Capitellidae

- Family Cossunidae

- Family Maldanidae

- Family Ophelidae

- Family Orbiniidae

- Family Paraonidae

- Family Parergodrilidae

- Family Potamodrilidae

- Family Psammodrilidae

- Family Questidae

- Family Scalibregmatidae

See also

- Epitoky, a form of reproduction of Polychaetae.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Briggs, D.E.G.; Kear, A.J. (1993), "Decay and preservation of polychaetes; taphonomic thresholds in soft-bodied organisms", Paleobiology 19 (1): 107–135, http://paleobiol.geoscienceworld.org/cgi/content/abstract/19/1/107

- ↑ Conway Morris, S. and Peel, J.S. 2008. The earliest annelids: Lower Cambrian polychaetes from the Sirius Passet Lagerstätte, Peary Land, North Greenland. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 53 (1): 137–148.

- ↑ Miller, A.J. (2004), A Revised Morphology of Cloudina with Ecological and Phylogenetic Implications, http://ajm.pioneeringprojects.org/files/CloudinaPaper_Final.pdf, retrieved on 2007-04-24

- Campbell, Reece, and Mitchell. Biology. 1999.

- Rouse, Greg W.; Fauchald, Kristian (1998). "Recent views on the status, delineation, and classification of the Annelida". American Zoologist 38: 953–964. doi:.

External links

- Special issue dedicated to polychaete published in Marine Ecology. Read the article abstracts online