Poisson distribution

Probability mass function The horizontal axis is the index k. The function is only defined at integer values of k (empty lozenges). The connecting lines are only guides for the eye. |

|

Cumulative distribution function The horizontal axis is the index k. The CDF is discontinuous at the integers of k and flat everywhere else because a variable that is Poisson distributed only takes on integer values. |

|

| Parameters |  |

|---|---|

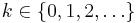

| Support |  |

| Probability mass function (pmf) |  |

| Cumulative distribution function (cdf) |

(where |

| Mean |  |

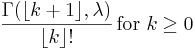

| Median |  |

| Mode |  and and  if if  is an integer is an integer |

| Variance |  |

| Skewness |  |

| Excess kurtosis |  |

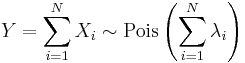

| Entropy | ![\lambda[1\!-\!\log(\lambda)]\!+\!e^{-\lambda}\sum_{k=0}^\infty \frac{\lambda^k\log(k!)}{k!}](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/b27b6cadba5878e13c577c34813aa485.png)

(for large |

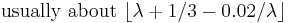

| Moment-generating function (mgf) |  |

| Characteristic function |  |

In probability theory and statistics, the Poisson distribution is a discrete probability distribution that expresses the probability of a number of events occurring in a fixed period of time if these events occur with a known average rate and independently of the time since the last event. The Poisson distribution can also be used for the number of events in other specified intervals such as distance, area or volume.

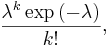

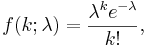

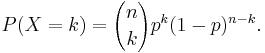

The distribution was discovered by Siméon-Denis Poisson (1781–1840) and published, together with his probability theory, in 1838 in his work Recherches sur la probabilité des jugements en matières criminelles et matière civile ("Research on the Probability of Judgments in Criminal and Civil Matters"). The work focused on certain random variables N that count, among other things, a number of discrete occurrences (sometimes called "arrivals") that take place during a time-interval of given length. If the expected number of occurrences in this interval is λ, then the probability that there are exactly k occurrences (k being a non-negative integer, k = 0, 1, 2, ...) is equal to

where

- e is the base of the natural logarithm (e = 2.71828...)

- k is the number of occurrences of an event - the probability of which is given by the function

- k! is the factorial of k

- λ is a positive real number, equal to the expected number of occurrences that occur during the given interval. For instance, if the events occur on average 4 times per minute, and you are interested in the number of events occurring in a 10 minute interval, you would use as model a Poisson distribution with λ = 10*4 = 40.

As a function of k, this is the probability mass function. The Poisson distribution can be derived as a limiting case of the binomial distribution.

The Poisson distribution can be applied to systems with a large number of possible events, each of which is rare. A classic example is the nuclear decay of atoms.

The Poisson distribution is sometimes called a Poissonian, analogous to the term Gaussian for a Gauss or normal distribution.

Contents |

Poisson noise and characterizing small occurrences

The parameter λ is not only the mean number of occurrences  , but also its variance

, but also its variance  (see Table). Thus, the number of observed occurrences fluctuates about its mean λ with a standard deviation

(see Table). Thus, the number of observed occurrences fluctuates about its mean λ with a standard deviation  . These fluctuations are denoted as Poisson noise or (particularly in electronics) as shot noise.

. These fluctuations are denoted as Poisson noise or (particularly in electronics) as shot noise.

The correlation of the mean and standard deviation in counting independent, discrete occurrences is useful scientifically. By monitoring how the fluctuations vary with the mean signal, one can estimate the contribution of a single occurrence, even if that contribution is too small to be detected directly. For example, the charge e on an electron can be estimated by correlating the magnitude of an electric current with its shot noise. If N electrons pass a point in a given time t on the average, the mean current is I = eN / t; since the current fluctuations should be of the order  (i.e. the standard deviation of the Poisson process), the charge e can be estimated from the ratio

(i.e. the standard deviation of the Poisson process), the charge e can be estimated from the ratio  . An everyday example is the graininess that appears as photographs are enlarged; the graininess is due to Poisson fluctuations in the number of reduced silver grains, not to the individual grains themselves. By correlating the graininess with the degree of enlargement, one can estimate the contribution of an individual grain (which is otherwise too small to be seen unaided). Many other molecular applications of Poisson noise have been developed, e.g., estimating the number density of receptor molecules in a cell membrane.

. An everyday example is the graininess that appears as photographs are enlarged; the graininess is due to Poisson fluctuations in the number of reduced silver grains, not to the individual grains themselves. By correlating the graininess with the degree of enlargement, one can estimate the contribution of an individual grain (which is otherwise too small to be seen unaided). Many other molecular applications of Poisson noise have been developed, e.g., estimating the number density of receptor molecules in a cell membrane.

Related distributions

- If

and

and  then the difference

then the difference  follows a Skellam distribution.

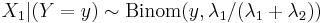

follows a Skellam distribution. - If

and

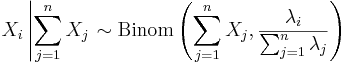

and  are independent, and

are independent, and  , then the distribution of

, then the distribution of  conditional on

conditional on  is a binomial. Specifically,

is a binomial. Specifically,  . More generally, if X1, X2,..., Xn are independent Poisson random variables with parameters λ1, λ2,..., λn then

. More generally, if X1, X2,..., Xn are independent Poisson random variables with parameters λ1, λ2,..., λn then

- The Poisson distribution can be derived as a limiting case to the binomial distribution as the number of trials goes to infinity and the expected number of successes remains fixed. Therefore it can be used as an approximation of the binomial distribution if n is sufficiently large and p is sufficiently small. There is a rule of thumb stating that the Poisson distribution is a good approximation of the binomial distribution if n is at least 20 and p is smaller than or equal to 0.05. According to this rule the approximation is excellent if n ≥ 100 and np ≤ 10.[1]

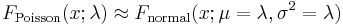

- For sufficiently large values of λ, (say λ>1000), the normal distribution with mean λ, and variance λ, is an excellent approximation to the Poisson distribution. If λ is greater than about 10, then the normal distribution is a good approximation if an appropriate continuity correction is performed, i.e., P(X ≤ x), where (lower-case) x is a non-negative integer, is replaced by P(X ≤ x + 0.5).

- Variance stabilizing transformation: When a variable is Poisson distributed, its square root is approximately normally distributed with expected value of about

and variance of about 1/4.[2] Under this transformation, the convergence to normality is far faster than the untransformed variable.

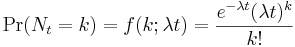

and variance of about 1/4.[2] Under this transformation, the convergence to normality is far faster than the untransformed variable. - If the number of arrivals in a given time follows the Poisson distribution, with mean =

, then the lengths of the inter-arrival times follow the Exponential distribution, with mean

, then the lengths of the inter-arrival times follow the Exponential distribution, with mean  .

.

Occurrence

The Poisson distribution arises in connection with Poisson processes. It applies to various phenomena of discrete nature (that is, those that may happen 0, 1, 2, 3, ... times during a given period of time or in a given area) whenever the probability of the phenomenon happening is constant in time or space. Examples of events that may be modelled as a Poisson distribution include:

- The number of soldiers killed by horse-kicks each year in each corps in the Prussian cavalry. This example was made famous by a book of Ladislaus Josephovich Bortkiewicz (1868–1931).

- The number of phone calls at a call centre per minute.

- The number of times a web server is accessed per minute.

- The number of mutations in a given stretch of DNA after a certain amount of radiation.

[Note: the intervals between successive Poisson events are reciprocally-related, following the Exponential distribution. For example, the lifetime of a lightbulb, or waiting time between buses.]

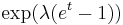

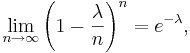

How does this distribution arise? — The law of rare events

In several of the above examples—for example, the number of mutations in a given sequence of DNA—the events being counted are actually the outcomes of discrete trials, and would more precisely be modelled using the binomial distribution. However, the binomial distribution with parameters n and λ/n, i.e., the probability distribution of the number of successes in n trials, with probability λ/n of success on each trial, approaches the Poisson distribution with expected value λ as n approaches infinity. This provides a means by which to approximate random variables using the Poisson distribution rather than the more-cumbersome binomial distribution.

This limit is sometimes known as the law of rare events, since each of the individual Bernoulli events rarely triggers. The name may be misleading because the total count of success events in a Poisson process need not be rare if the parameter λ is not small. For example, the number of telephone calls to a busy switchboard in one hour follows a Poisson distribution with the events appearing frequent to the operator, but they are rare from the point of the average member of the population who is very unlikely to make a call to that switchboard in that hour.

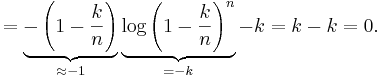

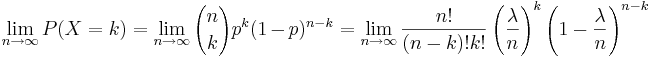

The proof may proceed as follows. First, recall from calculus

and the definition of the Binomal distribution

If the binomial probability can be defined such that  , we can evaluate the limit of

, we can evaluate the limit of  as

as  goes large

goes large

To evaluate the  term, we first take its logarithm

term, we first take its logarithm

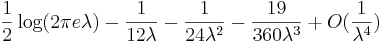

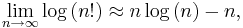

Using Stirling's approximation

the expression for  can be further simplified to

can be further simplified to

Therefore  .

.

Consequently, the limit of the distribution becomes

which now assumes the Poisson distribution.

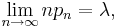

More generally, whenever a sequence of independent binomial random variables with parameters n and pn is such that

the sequence converges in distribution to a Poisson random variable with mean λ (see, e.g. law of rare events).

Properties

- The expected value of a Poisson-distributed random variable is equal to λ and so is its variance. The higher moments of the Poisson distribution are Touchard polynomials in λ, whose coefficients have a combinatorial meaning. In fact, when the expected value of the Poisson distribution is 1, then Dobinski's formula says that the nth moment equals the number of partitions of a set of size n.

- The mode of a Poisson-distributed random variable with non-integer λ is equal to

, which is the largest integer less than or equal to λ. This is also written as floor(λ). When λ is a positive integer, the modes are λ and λ − 1.

, which is the largest integer less than or equal to λ. This is also written as floor(λ). When λ is a positive integer, the modes are λ and λ − 1.

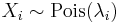

- Sums of Poisson-distributed random variables:

- If

follow a Poisson distribution with parameter

follow a Poisson distribution with parameter  and

and  are independent, then

are independent, then  also follows a Poisson distribution whose parameter is the sum of the component parameters.

also follows a Poisson distribution whose parameter is the sum of the component parameters.

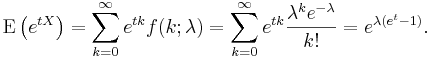

- The moment-generating function of the Poisson distribution with expected value λ is

- All of the cumulants of the Poisson distribution are equal to the expected value λ. The nth factorial moment of the Poisson distribution is λn.

- The Poisson distributions are infinitely divisible probability distributions.

- The directed Kullback-Leibler divergence between Pois(λ) and Pois(λ0) is given by

Generating Poisson-distributed random variables

A simple way to generate random Poisson-distributed numbers is given by Knuth, see References below.

algorithm poisson random number (Knuth):

init:

Let L ← e−λ, k ← 0 and p ← 1.

do:

k ← k + 1.

Generate uniform random number u in [0,1] and let p ← p × u.

while p ≥ L.

return k − 1.

While simple, the complexity is linear in λ. There are many other algorithms to overcome this. Some are given in Ahrens & Dieter, see References below.

Parameter estimation

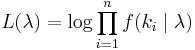

Maximum likelihood

Given a sample of n measured values ki we wish to estimate the value of the parameter λ of the Poisson population from which the sample was drawn. To calculate the maximum likelihood value, we form the log-likelihood function

Take the derivative of L with respect to λ and equate it to zero:

Solving for λ yields the maximum-likelihood estimate of λ:

Since each observation has expectation λ so does this sample mean. Therefore it is an unbiased estimator of λ. It is also an efficient estimator, i.e. its estimation variance achieves the Cramér-Rao lower bound (CRLB).

Bayesian inference

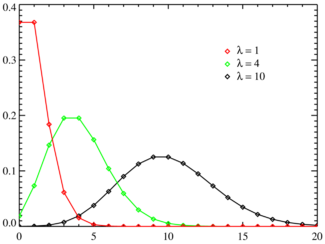

In Bayesian inference, the conjugate prior for the rate parameter λ of the Poisson distribution is the Gamma distribution. Let

denote that λ is distributed according to the Gamma density g parameterized in terms of a shape parameter α and an inverse scale parameter β:

Then, given the same sample of n measured values ki as before, and a prior of Gamma(α, β), the posterior distribution is

The posterior mean E[λ] approaches the maximum likelihood estimate  in the limit as

in the limit as  .

.

The posterior predictive distribution of additional data is a Gamma-Poisson (i.e. negative binomial) distribution.

The "law of small numbers"

The word law is sometimes used as a synonym of probability distribution, and convergence in law means convergence in distribution. Accordingly, the Poisson distribution is sometimes called the law of small numbers because it is the probability distribution of the number of occurrences of an event that happens rarely but has very many opportunities to happen. The Law of Small Numbers is a book by Ladislaus Bortkiewicz about the Poisson distribution, published in 1898. Some historians of mathematics have argued that the Poisson distribution should have been called the Bortkiewicz distribution.[3]

See also

- Anscombe transform - a variance-stabilising transformation for the Poisson distribution

- Compound Poisson distribution

- Tweedie distributions

- Poisson process

- Poisson regression

- Poisson sampling

- Queueing theory

- Erlang distribution which describes the waiting time until n events have occurred. For temporally distributed events, the Poisson distribution is the probability distribution of the number of events that would occur within a preset time, the Erlang distribution is the probability distribution of the amount of time until the nth event.

- Skellam distribution, the distribution of the difference of two Poisson variates, not necessarily from the same parent distribution.

- Incomplete gamma function used to calculate the CDF.

- Dobinski's formula (on combinatorial interpretation of the moments of the Poisson distribution)

- Schwarz formula

- Robbins lemma, a lemma relevant to empirical Bayes methods relying on the Poisson distribution

- Coefficient of dispersion, a simple measure to assess whether observed events are close to Poisson

Online Visualization Tools

Notes

- ↑ NIST/SEMATECH, '6.3.3.1. Counts Control Charts', e-Handbook of Statistical Methods, accessed 25 October 2006

- ↑ McCullagh, Peter; Nelder, John (1989). Generalized Linear Models. London: Chapman and Hall. ISBN 0-412-31760-5. page 196 gives the approximation and the subsequent terms.

- ↑ p.e. I J Good, Some statistical applications of Poisson's work, Statist. Sci. 1 (2) (1986), 157-180. JSTOR link

References

- Donald E. Knuth (1969). Seminumerical Algorithms. The Art of Computer Programming, Volume 2. Addison Wesley.

- Joachim H. Ahrens, Ulrich Dieter (1974). "Computer Methods for Sampling from Gamma, Beta, Poisson and Binomial Distributions". Computing 12 (3): 223--246. doi:.

- Joachim H. Ahrens, Ulrich Dieter (1982). "Computer Generation of Poisson Deviates". ACM Transactions on Mathematical Software 8 (2): 163--179. doi:.

- Ronald J. Evans, J. Boersma, N. M. Blachman, A. A. Jagers (1988). "The Entropy of a Poisson Distribution: Problem 87-6". SIAM Review 30 (2): 314--317. doi:.

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

`

is the Incomplete gamma function and

is the Incomplete gamma function and  is the floor function)

is the floor function)

![=\lim_{n\to\infty}

\underbrace{\left[\frac{n!}{n^k\left(n-k\right)!}\right]}_F

\left(\frac{\lambda^k}{k!}\right)

\underbrace{\left(1-\frac{\lambda}{n}\right)^n}_{\approx\exp\left(-\lambda\right)}

\underbrace{\left(1-\frac{\lambda}{n}\right)^{-k}}_{\approx 1} =

F\exp\left(-\lambda\right)\left(\frac{\lambda^k}{k!}\right)](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/6e4d2a7d98fdc088fa2f17bb0075a31e.png)

![\lim_{n\to\infty} \log\left(F\right) =

\log\left(n!\right) - k\log\left(n\right) - \log\left[\left(n-k\right)!\right].](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/5cba20479384a094c32e224f1adbc553.png)

![\lim_{n\to\infty} \log\left(F\right) =

\left[n\log\left(n\right) - n\right] -

\left[k\log\left(n\right)\right] -

\left[\left(n-k\right)\log\left(n-k\right)-\left(n-k\right)\right]](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/fd2257a17dce9761e32a48205f6c3383.png)