Poetry of the United States

| Culture of the United States |

|

Architecture |

The poetry of the United States arose first during its beginnings as the constitutionally unified thirteen colonies (although before this, a strong oral tradition often likened to poetry existed among Native American societies[1]). Unsurprisingly, most of the early colonists' work relied on contemporary British models of poetic form, diction, and theme. However, in the 19th century, a distinctive American idiom began to emerge. By the later part of that century, when Walt Whitman was winning an enthusiastic audience abroad, poets from the United States had begun to take their place at the forefront of the English-language avant-garde.

This position was sustained into the 20th century to the extent that Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot were perhaps the most influential English-language poets in the period during World War I.[2] By the 1960s, the young poets of the British Poetry Revival looked to their American contemporaries and predecessors as models for the kind of poetry they wanted to write. Toward the end of the millennium, consideration of American poetry had diversified, as scholars placed an increased emphasis on poetry by women, African Americans, Hispanics, Chicanos and other subcultural groupings. Poetry, and creative writing in general, also tended to become more professionalized with the growth of creative writing programs in the English studies departments of campuses across the country.

Contents |

Poetry in the colonies

One of the first recorded poets of the British colonies was Anne Bradstreet (1612–1672), who remains one of the earliest known women poets who wrote in English.[3] The poems she published during her lifetime address religious and political themes. She also wrote tender evocations of home and family life, and of her love for her husband, many of which remained unpublished until the 20th century. Edward Taylor (1645–1729) wrote poems expounding Puritan virtues in a highly wrought metaphysical style that can be seen as typical of the early colonial period.[4]

This narrow focus on the Puritan ethic was, understandably, the dominant note of most of the poetry written in the colonies during the 17th and early 18th centuries. The earliest "secular" poetry published in New England was by Samuel Danforth in his "almanacks" for 1647-1649,[5] published at Cambridge; these included "puzzle poems" as well as poems on caterpillars, pigeons, earthquakes, and hurricanes. Of course, being a Puritan minister as well as a poet, Danforth never ventured far from a spiritual message.

Another distinctly American lyric voice of the colonial period was Phillis Wheatley, a slave whose book "Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral," was published in 1773. She was one of the best-known poets of her day, at least in the colonies, and her poems were typical of New England culture at the time, meditating on religious and classical ideas.[6][7]

The 18th century saw an increasing emphasis on America itself as fit subject matter for its poets. This trend is most evident in the works of Philip Freneau (1752–1832), who is also notable for the unusually sympathetic attitude to Native Americans shown in his writings, sometimes reflective of a skepticism toward Anglo-American culture and civilization.[8] However, as might be expected from what was essentially provincial writing, this late colonial poetry is generally somewhat old-fashioned in form and syntax, deploying the means and methods of Pope and Gray in the era of Blake and Burns.

On the whole, the development of poetry in the American colonies mirrors the development of the colonies themselves. The early poetry is dominated by the need to preserve the integrity of the Puritan ideals that created the settlement in the first place. As the colonists grew in confidence, the poetry they wrote increasingly reflected their drive towards independence. This shift in subject matter was not reflected in the mode of writing which tended to be conservative, to say the least. This can be seen as a product of the physical remove at which American poets operated from the center of English-language poetic developments in London.

Postcolonial poetry

The first significant poet of the independent United States was William Cullen Bryant (1794–1878), whose great contribution was to write rhapsodic poems on the grandeur of prairies and forests. Other notable poets to emerge in the early and middle 19th century include Ralph Waldo Emerson , (1803–1882), Henry Wadsworth Longfellow (1807–1882), John Greenleaf Whittier (1807–1892), Edgar Allan Poe (1809–1849), Oliver Wendell Holmes (1809–1894), Henry David Thoreau (1817–1862), James Russell Lowell (1819–1891), and Sidney Lanier (1842–1881). As might be expected, the works of these writers are united by a common search for a distinctive American voice to distinguish them from their British counterparts. To this end, they explored the landscape and traditions of their native country as materials for their poetry.[9]

The most significant example of this tendency may be The Song of Hiawatha by Longfellow. This poem uses Native American tales collected by Henry Rowe Schoolcraft, who was superintendent of Indian affairs for Michigan from 1836 to 1841. Longfellow also imitated the meter of the Finnish epic poem Kalevala, possibly to avoid British models. The resulting poem, while a popular success, did not provide a model for future U.S. poets.

Another factor that distinguished these poets from their British contemporaries was the influence of the transcendentalism of the poet/philosophers Emerson and Thoreau. Transcendentalism was the distinctly American strain of English Romanticism that began with William Wordsworth and Samuel Taylor Coleridge. Emerson, arguably one of the founders of transcendentalism, had visited England as a young man to meet these two English poets, as well as Thomas Carlyle. While Romanticism transitioned into Victorianism in post-reform England, it grew more energetic in America from the 1830s through to the Civil War.

Edgar Allan Poe was probably the most recognized American poet outside of America during this period. Diverse authors in France, Sweden and Russia were heavily influenced by his works, and his poem "The Raven" swept across Europe, translated into many languages. In the twentieth century the American poet William Carlos Williams said of Poe that he is the only solid ground on which American poetry is anchored.

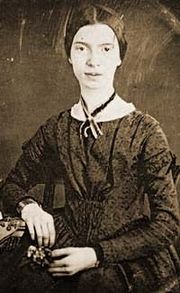

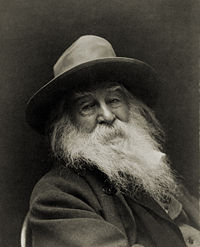

Whitman and Dickinson

The final emergence of a truly indigenous English-language poetry in the United States was the work of two poets, Walt Whitman (1819–1892) and Emily Dickinson (1830–1886). On the surface, these two poets could not have been less alike. Whitman's long lines, derived from the metric of the King James Version of the Bible, and his democratic inclusiveness stand in stark contrast with Dickinson's concentrated phrases and short lines and stanzas, derived from Protestant hymnals.

What links them is their common connection to Emerson (a passage from whom Whitman printed on the second edition of Leaves of Grass), and the daring originality of their visions. These two poets can be said to represent the birth of two major American poetic idioms—the free metric and direct emotional expression of Whitman, and the gnomic obscurity and irony of Dickinson—both of which would profoundly stamp the American poetry of the 20th century.[10]

The development of these idioms can be traced through the works of poets such as Edwin Arlington Robinson (1869–1935), Stephen Crane (1871–1900), Robert Frost (1874–1963) and Carl Sandburg (1878–1967). As a result, by the beginning of the 20th century the outlines of a distinctly new poetic tradition were clear to see.

Modernism and after

This new idiom, combined with a study of 19th-century French poetry, formed the basis of the United States input into 20th-century English-language poetic modernism. Ezra Pound (1885–1972) and T. S. Eliot (1888–1965) were the leading figures at the time, but numerous other poets made important contributions. These included Gertrude Stein (1874–1946), Wallace Stevens (1879–1955), William Carlos Williams (1883–1963), Hilda Doolittle (H.D.) (1886–1961), Adelaide Crapsey (1878-1914), Marianne Moore (1887–1972), E. E. Cummings (1894–1962), and Hart Crane (1899–1932). Williams was to become exemplary for many later poets because he, more than any of his peers, contrived to marry spoken American English with free verse rhythms.

While these poets were unambiguously aligned with High modernism, other poets active in the United States in the first third of the 20th century were not. Among the most important of the latter were those who were associated with what came to be known as the New Criticism. These included John Crowe Ransom (1888–1974), Allen Tate (1899–1979), and Robert Penn Warren (1905–1989). Other poets of the era, such as Archibald MacLeish (1892–1982), experimented with modernist techniques but were also drawn towards more traditional modes of writing. The modernist torch was carried in the 1930s mainly by the group of poets known as the Objectivists. These included Louis Zukofsky (1904–1978), Charles Reznikoff (1894–1976), George Oppen (1908–1984), Carl Rakosi (1903–2004) and, later, Lorine Niedecker (1903–1970). Kenneth Rexroth, who was published in the Objectivist Anthology, was, along with Madeline Gleason (1909–1973), a forerunner of the San Francisco Renaissance.

Many of the Objectivists came from urban communities of new immigrants, and this new vein of experience and language enriched the growing American idiom. Another source of enrichment was the emergence into the American poetic mainstream of African American poets such as Langston Hughes (1902–1967) and Countee Cullen (1903–1946).

World War II and after

Archibald Macleish called John Gillespie Magee, Jr. "the first poet of the war".[11]

World War II saw the emergence of a new generation of poets, many of whom were influenced by Wallace Stevens. Richard Eberhart (1904–2005), Karl Shapiro (1913–2000), Randall Jarrell (1914–1965) and James Dickey (1923-1997) all wrote poetry that sprang from experience of active service. Together with Elizabeth Bishop (1911–1979), Theodore Roethke (1908–1963) and Delmore Schwartz (1913–1966), they formed a generation of poets that in contrast to the preceding generation often wrote in traditional verse forms.

After the war, a number of new poets and poetic movements emerged. John Berryman (1914–1972) and Robert Lowell (1917–1977) were the leading lights in what was to become known as the Confessional movement, which was to have a strong influence on later poets like Sylvia Plath (1932–1963) and Anne Sexton (1928–1974). Though both Berryman and Lowell were closely acquainted with Modernism, they were mainly interested in exploring their own experiences as subject matter and a style that Lowell referred to as "cooked" -- that is, consciously and carefully crafted.

In contrast, the Beat poets, who included such figures as Jack Kerouac (1922–1969), Allen Ginsberg (1926–1997), Gregory Corso (1930–2001), Joanne Kyger (born 1934), Gary Snyder (born 1930), Diane Di Prima (born 1934), Amiri Baraka (born 1934) and Lawrence Ferlinghetti (born 1919), were distinctly raw. Reflecting, sometimes in an extreme form, the more open, relaxed and searching society of the 1950s and 1960s, the Beats pushed the boundaries of the American idiom in the direction of demotic speech perhaps further than any other group.

Around the same time, the Black Mountain poets, under the leadership of Charles Olson (1910–1970), were working at Black Mountain College. These poets were exploring the possibilities of open form but in a much more programmatic way than the Beats. The main poets involved were Robert Creeley (1926–2005), Robert Duncan (1919–1988), Denise Levertov (1923–1997), Ed Dorn (1929–1999), Paul Blackburn (1926–1971), Hilda Morley (1916–1998), John Wieners (1934–2002), and Larry Eigner (1927–1996). They based their approach to poetry on Olson's 1950 essay Projective Verse, in which he called for a form based on the line, a line based on human breath and a mode of writing based on perceptions juxtaposed so that one perception leads directly to another.

Other poets often associated with the Black Mountain are Cid Corman (1924–2004) and Theodore Enslin (born 1925), though they are perhaps more correctly viewed as direct descendants of the Objectivists. And one-time Black Mountain College resident, composer John Cage (1912–1992), along with Jackson Mac Low (1922–2004), wrote poetry based on chance or aleatory techniques. Inspired by Zen, Dada and scientific theories of indeterminacy, they were to prove to be important influences on the 1970s U.S avant-garde.

The Beats and some of the Black Mountain poets are often considered to have been responsible for the San Francisco Renaissance. However, as previously noted, San Francisco had become a hub of experimental activity from the 1930s thanks to Kenneth Rexroth and Gleason. Other poets involved in this scene included Charles Bukowski (1920–1994) and Jack Spicer (1925–1965). These poets sought to combine a contemporary spoken idiom with inventive formal experiment.

Jerome Rothenberg (born 1931) is well-known for his work in ethnopoetics, but he was also the coiner of the term "deep image," which he used to described the work of poets like Robert Kelly (born 1935), Diane Wakoski (born 1937) and Clayton Eshleman (born 1935). Deep Image poetry was inspired by the symbolist theory of correspondences, in particular the work of Spanish poet Federico García Lorca. The term was later taken up and popularized by Robert Bly. The Deep Image movement was also the most international, accompanied by a flood of new translations from Latin American and European poets such as Pablo Neruda, César Vallejo and Tomas Tranströmer. Some of the poets who became associated with Deep Image are Galway Kinnell, James Wright, Mark Strand and W. S. Merwin. Both Merwin and California poet Gary Snyder would also become known for their interest in environmental and ecological concerns.

The Small Press poets (sometimes called the mimeograph movement) are another influential and eclectic group of poets who also surfaced in the San Francisco Bay Area in the late 1950s and are still active today. Fiercely independent editors, who were also poets, edited and published low-budget periodicals and chapbooks of emerging poets who might otherwise have gone unnoticed. This work ranged from formal to experimental. Gene Fowler, A.D. Winans, Hugh Fox, street poet and activist Jack Hirschman, Paul Foreman, John Bennett, Stephen Morse (born 1945), Judy L. Brekke, and F. A. Nettelbeck are among the many poets who are still actively continuing the Small Press Poets tradition. Many have turned to the new medium of the Web for its distribution capabilities.

Just as the West Coast had the San Francisco Renaissance and the Small Press Movement, the East Coast produced the New York School. This group aimed to write poetry that spoke directly of everyday experience in everyday language and produced a poetry of urbane wit and elegance that contrasts with the work of their Beat contemporaries (though in other ways, including their mutual respect for American slang and disdain for academic or "cooked" poetry, they were similar). Leading members of the group include John Ashbery (born 1927), Frank O'Hara (1926–1966), Kenneth Koch (1925–2002), James Schuyler (1923–1991), Richard Howard (born 1929), Ted Berrigan (1934–1983), Anne Waldman (born 1945) and Bernadette Mayer (born 1945). Of this group, John Ashbery, in particular, has emerged as a defining force in recent poetics, and he is regarded by many as the most important American poet since World War II.

American poetry today

The last thirty years in United States poetry have seen the emergence of a number of groups, schools and trends, whose lasting importance has yet to be shown.

The 1970s saw a revival of interest in surrealism, with the most prominent poets working in this field being Andrei Codrescu (born 1946), Russell Edson (born 1935) and Maxine Chernoff (born 1952). Performance poetry also emerged from the Beat and hippie happenings, and the talk-poems of David Antin (born 1932) and ritual events performed by Rothenberg, to become a serious poetic stance which embraces multiculturalism and a range of poets from a multiplicity of cultures. This mirrored a general growth of interest in poetry by African Americans including Gwendolyn Brooks (born 1917), Maya Angelou (born 1928), Ishmael Reed (born 1938) and Nikki Giovanni (born 1943).

Another group of poets, the Language school (or L=A=N=G=U=A=G=E, after the magazine that bears that name), have continued and extended the Modernist and Objectivist traditions of the 1930s. Some poets associated with the group are Lyn Hejinian, Ron Silliman, Bob Perelman and Leslie Scalapino. Their poems -- fragmentary, purposefully ungrammatical, sometimes mixing texts from different sources and idioms -- can be by turns abstract, lyrical, and highly comic. Critics of the Language school point out that, by abandoning sense and context, their poetry could just as well be written by the proverbial infinite roomful of monkeys with typewriters.

The Language school includes a high proportion of women, which mirrors another general trend -- the rediscovery and promotion of poetry written both by earlier and contemporary women poets. A number of the most prominent African American poets to emerge are women, and other prominent women writers include Adrienne Rich (born 1929), Jean Valentine (born 1934) and Amy Gerstler (born 1956).

Although poetry in traditional classical forms had mostly fallen out of fashion by the 1960s, the practice was kept alive by poets of great formal virtuosity like James Merrill (1926–1995), author of the epic poem The Changing Light at Sandover (1982), and British-born San Francisco poet Thom Gunn. The 1980s and 1990's saw a re-emergent interest in traditional form, sometimes dubbed New Formalism or Neoformalism. These include poets such as Molly Peacock, Brad Leithauser, Dana Gioia and Marilyn Hacker. Some of the more outspoken New Formalists have declared that the return to rhyme and more fixed meters to be the new avant-garde. Their critics sometimes associate this traditionalism with the conservative politics of the Reagan era, noting the recent appointment of Gioia as Chair of the National Endowment for the Arts. More recent examples of New Formalism, however, have sometimes crossed over into the more experimental territory of Language poetry, suggesting that both schools are being gradually absorbed into the poetic mainstream.

The last two decades have also seen a revival of the Beat poetry spoken word tradition, in the form of the poetry slam. Devised in 1984, by Chicago construction worker Marc Smith, these competitive audience-judged poetry performances emphasize a style of writing that is topical, provocative and easily understood. Poetry slam opened the door for a new generation of writers and spoken word performers, including Alix Olson, Taylor Mali, and Saul Williams, and inspired hundreds of open mics across the country. Poetry has also become a significant presence on the Web, with a number of new online journals, 'zines, blogs and other websites.

In general, however, poetry has been moving out of the mainstream and onto the college and university campus. The growth in the popularity of graduate creative writing programs has given poets the opportunity to make a living as teachers. This increased professionalization, combined with the reluctance of most major book and magazine presses to publish poetry, has meant that, for the foreseeable future at least, poetry may have found its new home in the academy.

See also

- List of poets from the United States

- List of national poetries

- Academy of American Poets

- Chicano poetry

References

- ↑ Einhorn, Lois J. The Native American Oral Tradition: Voices of the Spirit and Soul (ISBN 027595790X)

- ↑ Aldridge, John (1958). After the Lost Generation: A Critical Study of the Writers of Two Wars. Noonday Press. Original from the University of Michigan Digitized Mar 31, 2006.

- ↑ Moulton, Charles (1901). The Library of Literary Criticism of English and American Authors. The Moulton Publishing Company. Original from the New York Public Library Digitized Oct 27, 2006.Anne Bradstreet: "our earliest woman poet"

- ↑ Davis, Virginia (1997). The Tayloring Shop: Essays on the Poetry of Edward Taylor. University of Delaware Press. ISBN 0874136237.

- ↑ Danforth, Samuel. "Almanacks"

- ↑ Williams, George (1882). History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880. G.P. Putnam's Sons. Original from Harvard University Digitized Aug 18, 2006.

- ↑ Gregson, Susan (2002). Phillis Wheatley. Capstone Press. ISBN 0736810331.

- ↑ Lubbers, Klaus (1994). Born for the Shade: Stereotypes of the Native American in United States Literature and the Visual Arts, 1776-1894. Rodopi. ISBN 9051836287.

- ↑ Lucy Larcom: Landscape in American Poetry (1879).

- ↑ Untermeyer, Louis (1921). Modern American Poetry. Harcourt, Brace and Company. Original from the New York Public Library Digitized Oct 6, 2006.

- ↑ http://www.qunl.com/rees0008.html

- Baym, Nina, et al (eds.): The Norton Anthology of American Literature (Shorter sixth edition, 2003). ISBN 0-393-97969-5

- Cavitch, Max, American Elegy: The Poetry of Mourning from the Puritans to Whitman (University of Minnesota Press, 2007). ISBN 081664893X

- Hoover, Paul (ed): Postmodern American Poetry - A Norton Anthology (1994). ISBN 0-393-31090-6

- Moore, Geoffrey (ed): The Penguin Book of American Verse (Revised edition 1983) ISBN 0-14-042313-3

External links

- Cary Nelson, Ed. (1999-2002) Poet biographies at Modern American Poetry. Retrieved December 5, 2004

- Poet biographies at the Academy of American Poets Captured December 10, 2004

- Poet biographies at the Electronic Poetry Centre Captured December 10, 2004

- Various anthologies of American verse at Bartleby.com Captured December 10, 2004

- Poetry Resource a website for students of poetry

|

|||||