Planar graph

| Example graphs | |

|---|---|

| Planar | Nonplanar |

|

K5 |

The complete graph K4 is planar |

K3,3 |

In graph theory, a planar graph is a graph which can be embedded in the plane, i.e., it can be drawn on the plane in such a way that its edges intersect only at their endpoints.

A nonplanar graph is the one which cannot be drawn in the plane without edge intersections.

A planar graph already drawn in the plane without edge intersections is called a plane graph or planar embedding of the graph. A plane graph can be defined as a planar graph with a mapping from every node to a point in 2D space, and from every edge to a plane curve, such that the extreme points of each curve are the points mapped from its end nodes, and all curves are disjoint except on their extreme points.

It is easily seen that a graph that can be drawn on the plane can be drawn on the sphere as well, and vice versa.

The equivalence class of topologically equivalent drawings on the sphere is called a planar map. Although a plane graph has an external or unbounded face, none of the faces of a planar map have a particular status.

A generalization of planar graphs are graphs which can be drawn on a surface of a given genus. In this terminology, planar graphs have graph genus 0, since the plane (and the sphere) are surfaces of genus 0. See "graph embedding" for other related topics.

Contents |

Kuratowski's and Wagner's theorems

The Polish mathematician Kazimierz Kuratowski provided a characterization of planar graphs in terms of forbidden graphs, now known as Kuratowski's theorem:

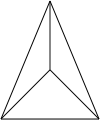

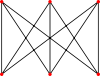

- A finite graph is planar if and only if it does not contain a subgraph that is a subdivision of K5 (the complete graph on five vertices) or K3,3 (complete bipartite graph on six vertices, three of which connect to each of the other three).

A subdivision of a graph results from inserting vertices into edges (for example, changing an edge •——• to •—•—•) zero or more times. Equivalent formulations of this theorem, also known as "Theorem P" include

- A finite graph is planar if and only if it does not contain a subgraph that is homeomorphic to K5 or K3,3.

In the Soviet Union, Kuratowski's theorem was known as the Pontryagin-Kuratowski theorem, as its proof was allegedly first given in Pontryagin's unpublished notes. By a long-standing academic tradition, such references are not taken into account in determining priority, so the Russian name of the theorem is not acknowledged internationally.

Instead of considering subdivisions, Wagner's theorem deals with minors:

- A finite graph is planar if and only if it does not have K5 or K3,3 as a minor.

Klaus Wagner asked more generally whether any minor-closed class of graphs is determined by a finite set of "forbidden minors". This is now the Robertson-Seymour theorem, proved in a long series of papers. In the language of this theorem, K5 and K3,3 are the forbidden children for the class of finite planar graphs.

Other planarity criteria

In practice, it is difficult to use Kuratowski's criterion to quickly decide whether a given graph is planar. However, there exist fast algorithms for this problem: for a graph with n vertices, it is possible to determine in time O(n) (linear time) whether the graph may be planar or not (see planarity testing).

For a simple, connected, planar graph with v vertices and e edges, the following simple planarity criteria hold:

- Theorem 1. If v ≥ 3 then e ≤ 3v - 6;

- Theorem 2. If v > 3 and there are no cycles of length 3, then e ≤ 2v - 4.

In this sense, planar graphs are sparse graphs, in that they have only O(v) edges, asymptotically smaller than the maximum O(v2). The graph K3,3, for example, has 6 vertices, 9 edges, and no cycles of length 3. Therefore, by Theorem 2, it cannot be planar. Note that these theorems provide necessary conditions for planarity that are not sufficient conditions, and therefore can only be used to prove a graph is not planar, not that it is planar. If both theorem 1 and 2 fail, other methods may be used.

For two planar graphs with v vertices, it is possible to determine in time O(v) whether they are isomorphic or not (see also graph isomorphism problem).[1]

- Whitney's planarity criterion gives a characterization based on the existence of an algebraic dual;

- MacLane's planarity criterion gives an algebraic characterization of finite planar graphs, via their cycle spaces;

- Fraysseix-Rosenstiehl's planarity criterion gives a characterization based on the existence of a bipartition of the cotree edges of a depth-first search tree. It is central to the left-right planarity testing algorithm;

- Schnyder's theorem gives a characterization of planarity in terms of partial order dimension;

- Colin de Verdière's planarity criterion gives a characterization based on the maximum multiplicity of the second eigenvalue of certain Schrödinger operators defined by the graph.

Euler's formula

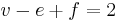

Euler's formula states that if a finite, connected, planar graph is drawn in the plane without any edge intersections, and v is the number of vertices, e is the number of edges and f is the number of faces (regions bounded by edges, including the outer, infinitely-large region), then

i.e. the Euler characteristic is 2. As an illustration, in the first planar graph given above, we have v=6, e=7 and f=3. If the second graph is redrawn without edge intersections, we get v=4, e=6 and f=4. Euler's formula can be proven as follows: if the graph isn't a tree, then remove an edge which completes a cycle. This lowers both e and f by one, leaving v − e + f constant. Repeat until you arrive at a tree; trees have v = e + 1 and f = 1, yielding v - e + f = 2.

In a finite, connected, simple, planar graph, any face (except possibly the outer one) is bounded by at least three edges and every edge touches at most two faces; using Euler's formula, one can then show that these graphs are sparse in the sense that e ≤ 3v - 6 if v ≥ 3.

A simple graph is called maximal planar if it is planar but adding any edge would destroy that property. All faces (even the outer one) are then bounded by three edges, explaining the alternative term triangular for these graphs. If a triangular graph has v vertices with v > 2, then it has precisely 3v-6 edges and 2v-4 faces.

Note that Euler's formula is also valid for simple polyhedra. This is no coincidence: every simple polyhedron can be turned into a connected, simple, planar graph by using the polyhedron's vertices as vertices of the graph and the polyhedron's edges as edges of the graph. The faces of the resulting planar graph then correspond to the faces of the polyhedron. For example, the second planar graph shown above corresponds to a tetrahedron. Not every connected, simple, planar graph belongs to a simple polyhedron in this fashion: the trees do not, for example. A theorem of Ernst Steinitz says that the planar graphs formed from convex polyhedra (equivalently: those formed from simple polyhedra) are precisely the finite 3-connected simple planar graphs.

Outerplanar graphs

A graph is called outerplanar if it has an embedding in the plane such that the vertices lie on a fixed circle and the edges lie inside the disk of the circle and don't intersect. Equivalently, there is some face that includes every vertex. Every outerplanar graph is planar, but the converse is not true: the second example graph shown above (K4) is planar but not outerplanar. This is the smallest non-outerplanar graph: a theorem similar to Kuratowski's states that a finite graph is outerplanar if and only if it does not contain a subgraph that is an expansion of K4 (the full graph on 4 vertices) or of K2,3 (five vertices, 2 of which connected to each of the other three for a total of 6 edges).

Properties of outerplanar graphs

All finite or countably infinite trees are outerplanar and hence planar.

An outerplanar graph without loops (edges with coinciding endvertices) has a vertex of degree at most 2.

All loopless outerplanar graphs are 3-colorable; this fact features prominently in the simplified proof of Chvátal's art gallery theorem by Fisk (1978). A 3-coloring may be found easily by removing a degree-2 vertex, coloring the remaining graph recursively, and adding back the removed vertex with a color different from its two neighbors.

k-outerplanar graphs

A 1-outerplanar embedding of a graph is the same as an outerplanar embedding. For k > 1 a planar embedding is k-outerplanar if removing the vertices on the outer face results in a (k-1)-outerplanar embedding. A graph is k-outerplanar if it has a k-outerplanar embedding

Other facts and definitions

Every planar graph without loops is 4-partite, or 4-colorable; this is the graph-theoretical formulation of the four color theorem.

Fáry's theorem states that every simple planar graph admits an embedding in the plane such that all edges are straight line segments which don't intersect. Similarly, every simple outerplanar graph admits an embedding in the plane such that all vertices lie on a fixed circle and all edges are straight line segments that lie inside the disk and don't intersect.

Given an embedding G of a (not necessarily simple) planar graph in the plane without edge intersections, we construct the dual graph G* as follows: we choose one vertex in each face of G (including the outer face) and for each edge e in G we introduce a new edge in G* connecting the two vertices in G* corresponding to the two faces in G that meet at e. Furthermore, this edge is drawn so that it crosses e exactly once and that no other edge of G or G* is intersected. Then G* is again the embedding of a (not necessarily simple) planar graph; it has as many edges as G, as many vertices as G has faces and as many faces as G has vertices. The term "dual" is justified by the fact that G** = G; here the equality is the equivalence of embeddings on the sphere. If G is the planar graph corresponding to a convex polyhedron, then G* is the planar graph corresponding to the dual polyhedron.

Duals are useful because many properties of the dual graph are related in simple ways to properties of the original graph, enabling results to be proven about graphs by examining their dual graphs.

While the dual constructed for a particular embedding is unique (up to isomorphism), graphs may have different (i.e. non-isomorphic) duals, obtained from different (i.e. non-homeomorphic) embeddings.

A Euclidean graph is a graph in which the vertices represent points in the plane, and the edges are assigned lengths equal to the Euclidean distance between those points; see Geometric graph theory.

Applications

- Telecommunications - e.g. spanning trees

- Vehicle routing - e.g. planning routes on roads without underpasses

- VLSI - e.g. laying out circuits on computer chips[2]

External links

- Edge Addition Planarity Algorithm Source Code — Free C source code for reference implementation of Boyer-Myrvold planarity algorithm, which provides both a combinatorial planar embedder and Kuratowski subgraph isolator.

- Public Implementation of a Graph Algorithm Library and Editor — GPL graph algorithm library including planarity testing, planarity embedder and Kuratowski subgraph exhibition in linear time.

- 3 Utilities Puzzle and Planar Graphs

- Planarity — A puzzle game created by John Tantalo.

References

- Kuratowski, Kazimierz (1930), "Sur le problème des courbes gauches en topologie", Fund. Math. 15: 271–283, http://matwbn.icm.edu.pl/ksiazki/fm/fm15/fm15126.pdf.

- Wagner, K. (1937), "Über eine Eigenschaft der ebenen Komplexe", Math. Ann. 114: 570–590.

- Boyer, John M.; Myrvold, Wendy J. (2005), "On the cutting edge: Simplified O(n) planarity by edge addition", Journal of Graph Algorithms and Applications 8 (3): 241–273, http://jgaa.info/accepted/2004/BoyerMyrvold2004.8.3.pdf.

- McKay, Brendan; Brinkmann, Gunnar, A useful planar graph generator, http://cs.anu.edu.au/~bdm/plantri/.

- de Fraysseix, H.; Ossona de Mendez, P.; Rosenstiehl, P. (2006), "Trémaux trees and planarity", International Journal of Foundations of Computer Science 17 (5): 1017–1029. Special Issue on Graph Drawing. doi:10.1142/S0129054106004248

- D.A. Bader and S. Sreshta, A New Parallel Algorithm for Planarity Testing, UNM-ECE Technical Report 03-002, October 1, 2003.

- Fisk, Steve (1978), "A short proof of Chvátal's watchman theorem", J. Comb. Theory, Ser. B 24: 374.

- ↑ I. S. Filotti, Jack N. Mayer. A polynomial-time algorithm for determining the isomorphism of graphs of fixed genus. Proceedings of the 12th Annual ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, p.236–243. 1980.

- ↑ Nick Pearson, Planar graphs and the Travelling Salesman Problem, Lancaster University, April 19th 2005