Pineal gland

| Pineal gland | |

|---|---|

|

|

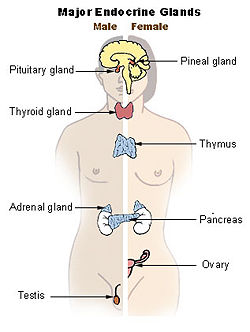

| Endocrine system | |

|

|

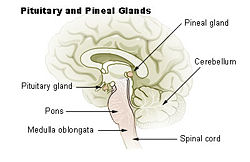

| Diagram of pituitary and pineal glands. | |

| Latin | glandula pinealis |

| Gray's | subject #276 1277 |

| Artery | superior cerebellar artery |

| MeSH | Pineal+gland |

The pineal gland (also called the pineal body, epiphysis cerebri, or epiphysis) is a small endocrine gland in the vertebrate brain. It produces melatonin, a hormone that affects the modulation of wake/sleep patterns and photoperiodic (seasonal) functions.[1][2] It is shaped like a tiny pine cone (hence its name), and is located near to the centre of the brain, between the two hemispheres, tucked in a groove where the two rounded thalamic bodies join.

Contents |

Location

The pineal gland is a reddish-gray body about the size of a pea (8 mm in humans), located just rostro-dorsal to the superior colliculus and behind and beneath the stria medullaris, between the laterally positioned thalamic bodies. It is part of the epithalamus.

The pineal gland is a midline structure, and is often seen in plain skull X-rays, as it is often calcified.

Structure and composition

The pineal body consists in humans of a lobular parenchyma of pinealocytes surrounded by connective tissue spaces. The gland's surface is covered by a pial capsule.

The pineal gland consists mainly of pinealocytes, but four other cell types have been identified.

| Cell type | Description |

| pinealocytes | The pinealocytes consist of a cell body with 4-6 processes emerging. They produce and secrete melatonin. The pinealocytes can be stained by special silver impregnation methods. |

| interstitial cells | Interstitial cells are located between the pinealocytes. |

| perivascular phagocyte | Many capillaries are present in the gland, and perivascular phagocytes are located close to these blood vessels. The perivascular phagocytes are antigen presenting cells. |

| pineal neurons | In higher vertebrates neurons are located in the pineal gland. However, these are not present in rodents. |

| peptidergic neuron-like cells | In some species, neuronal-like peptidergic cells are present. These cells might have a paracrine regulatory function. |

The pineal gland receives a sympathetic innervation from the superior cervical ganglion. However, a parasympathetic innervation from the sphenopalatine and otic ganglia is also present. Further, some nerve fibers penetrate into the pineal gland via the pineal stalk (central innervation). Finally, neurons in the trigeminal ganglion innervates the gland with nerve fibers containing the neuropeptide, PACAP. Human follicles contain a variable quantity of gritty material, called corpora arenacea (or "acervuli", or "brain sand"). Chemical analysis shows that they are composed of calcium phosphate, calcium carbonate, magnesium phosphate, and ammonium phosphate.[3] Recently, calcite deposits have been described as well.[4] Calcium and phosphorous deposits in the pineal gland have been linked with aging.[5]

Miscellaneous anatomy

Pinealocytes in many non-mammalian vertebrates have a strong resemblance to the photoreceptor cells of the eye. Some evolutionary biologists believe that the vertebrate pineal cells share a common evolutionary ancestor with retinal cells.[6]

In some vertebrates, exposure of the pineal to light can directly set off a chain reaction of enzymatic events which regulate circadian rhythms.[7] In humans and other mammals, this function is served by the retinohypothalamic system that sets the rhythm within the suprachiasmatic nucleus. Cultural and social interactions produce exposures to artificial light that influence the setting of the suprachiasmatic clock.

Some early vertebrate fossil skulls have a pineal foramen. This corroborates with the physiology of the modern lamprey, tuatara, and some other vertebrates.

Function

The pineal gland was originally believed to be a "vestigial remnant" of a larger organ (much as the appendix was thought to be a vestigial digestive organ). Aaron Lerner and colleagues at Yale University discovered that melatonin, the most potent compound then known to lighten frog skin, was present in the highest concentrations in the pineal.[8] Melatonin is a derivative of the amino acid tryptophan, which also has other functions in the central nervous system. The production of melatonin by the pineal gland is stimulated by darkness and inhibited by light.[9] Photosensitive cells in the retina detect light and directly signal the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN), entraining it to the 24 hour clock. Fibers project from the SCN to the paraventricular nuclei (PVN), which relay the circadian signals to the spinal cord and out via the sympathetic system to superior cervical ganglia (SCG), and from there into the pineal gland. The function(s) of melatonin in humans is not clear; it is commonly prescribed for the treatment of circadian rhythm sleep disorders.

The pineal gland is large in children, but shrinks at puberty. It appears to play a major role in sexual development, hibernation in animals, metabolism, and seasonal breeding. The abundant melatonin levels in children is believed to inhibit sexual development, and pineal tumors have been linked with precocious puberty. When puberty arrives, melatonin production is reduced. Calcification of the pineal gland is typical in adults.

Pineal cytostructure seems to have evolutionary similarities to the retinal cells of chordates.[10] Modern birds and reptiles have been found to express the phototransducing pigment melanopsin in the pineal gland. Avian pineal glands are believed to act like the suprachiasmatic nucleus in mammals.[11]

Studies suggest that in rodents the pineal gland may influence the actions of recreational drugs, such as cocaine,[12] and antidepressants, such as fluoxetine (Prozac),[13] and its hormone melatonin can protect against neurodegeneration.[14]

Cultures, philosophies and mythologies

The secretory activity of the pineal gland has only relatively recently become understood. Historically, its location deep in the brain suggested to philosophers that it possessed particular importance. This combination led to its being a "mystery" gland with myth, superstition and metaphysical theories surrounding its perceived function.

René Descartes, who dedicated much time to the study of the pineal gland,[15] called it the "seat of the soul".[16] He believed that it was the point of connection between the intellect and the body.[17] This was in part because of his belief that it is unique in the anatomy of the human brain in being a structure not duplicated on the right and left sides. This observation is not true, however; under a microscope one finds the pineal gland is divided into two fine hemispheres. Another theory was that the pineal operated as a valve releasing fluids, thus the position taken during deep thought, with the head slightly down meeting the hand, was an allowance for the opening of these 'valves'.

Writers such as Madame Blavatsky and Alice Bailey, considered early proponents of the new age movement, use the pineal-eye as a key element in their spiritual world-view...(see Alice Bailey: "A Treatise on White Magic", Madame Blavatsky: "The Secret Doctrine")

The notion of a 'pineal-eye' is also crucial to the philosophy of the seminal French writer Georges Bataille, which is analyzed at length by literary scholar Denis Hollier in his study Against Architecture.[18]

"But the head has a hole in it. The pineal eye, the organ of not-knowing, is the undoing of science. If science thought up man, the pineal eye unthinks him, spends him extravagantly, makes him lose the reserve in which, at the summit, from his head position, he was guarding himself."[19]

In this work Hollier discusses how Bataille uses the concept of a 'pineal-eye' as a reference to a blind-spot in Western rationality.

"When I carefully seek out, in deepest anguish, some strange absurdity, an eye opens at the top, in the middle of my skull. This eye opening up onto the sun in all its glory, to contemplate it in its nakedness, privately, is not the work of my reason: it is a cry escaping from me. For at the moment when the flash blinds me I am the splintering brilliance of a shattered life, and this life - agony and vertigo - opening up onto an infinite void, bursts and exhausts itself all at once in this void."[20]

The pineal gland also plays a role in the transformation of a scientist into a grotesque monster in the H. P. Lovecraft-inspired film From Beyond.

In Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas by Hunter S. Thompson, Raoul Duke and his attorney amuse themselves by tricking a clueless police officer into believing that gangs of drug freaks in Los Angeles routinely decapitate suburban families to harvest their pineal glands.[21] Later in the novel, the attorney frightens an adrenochrome-crazed Duke with various increasingly fantastical health defects that might result, should one eat extract of pineal gland as a psychoactive.

Additional images

References

- ↑ Macchi M, Bruce J (2004). "Human pineal physiology and functional significance of melatonin". Front Neuroendocrinol 25 (3-4): 177–95. doi:. PMID 15589268.

- ↑ Arendt J, Skene DJ (2005). "Melatonin as a chronobiotic". Sleep Med Rev 9 (1): 25–39. doi:. PMID 15649736. "Exogenous melatonin has acute sleepiness-inducing and temperature-lowering effects during 'biological daytime', and when suitably timed (it is most effective around dusk and dawn) it will shift the phase of the human circadian clock (sleep, endogenous melatonin, core body temperature, cortisol) to earlier (advance phase shift) or later (delay phase shift) times.".

- ↑ Bocchi G, Valdre G (1993). "Physical, chemical, and mineralogical characterization of carbonate-hydroxyapatite concretions of the human pineal gland". J Inorg Biochem 49 (3): 209–20. doi:. PMID 8381851.

- ↑ Baconnier S, Lang S, Polomska M, Hilczer B, Berkovic G, Meshulam G (2002). "Calcite microcrystals in the pineal gland of the human brain: first physical and chemical studies". Bioelectromagnetics 23 (7): 488–95. doi:. PMID 12224052.

- ↑ http://www.ingentaconnect.com/content/hum/bter/2007/00000119/00000002/art00004

- ↑ Klein D (2004). "The 2004 Aschoff/Pittendrigh lecture: Theory of the origin of the pineal gland--a tale of conflict and resolution". J Biol Rhythms 19 (4): 264–79. doi:. PMID 15245646.

- ↑ Moore RY, Heller A, Wurtman RJ, Axelrod J. Visual pathway mediating pineal response to environmental light. Science 1967;155(759):220–3. PMID 6015532

- ↑ Lerner AB, Case JD, Takahashi Y (1960). "Isolation of melatonin and 5-methoxyindole-3-acetic acid from bovine pineal glands". J Biol Chem 235: 1992–7. PMID 14415935.

- ↑ Axelrod J (1970). "The pineal gland". Endeavour 29 (108): 144–8. PMID 4195878.

- ↑ Klein D (2004). "The 2004 Aschoff/Pittendrigh lecture: Theory of the origin of the pineal gland--a tale of conflict and resolution". J Biol Rhythms 19 (4): 264–79. doi:. PMID 15245646.

- ↑ Natesan A, Geetha L, Zatz M (2002). "Rhythm and soul in the avian pineal". Cell Tissue Res 309 (1): 35–45. doi:. PMID 12111535.

- ↑ Uz T, Akhisaroglu M, Ahmed R, Manev H (2003). "The pineal gland is critical for circadian Period1 expression in the striatum and for circadian cocaine sensitization in mice". Neuropsychopharmacology 28 (12): 2117–23. doi:. PMID 12865893.

- ↑ Uz T, Dimitrijevic N, Akhisaroglu M, Imbesi M, Kurtuncu M, Manev H (2004). "The pineal gland and anxiogenic-like action of fluoxetine in mice". Neuroreport 15 (4): 691–4. doi:. PMID 15094477.

- ↑ Manev H, Uz T, Kharlamov A, Joo J (1996). "Increased brain damage after stroke or excitotoxic seizures in melatonin-deficient rats". FASEB J 10 (13): 1546–51. PMID 8940301.

- ↑ Descartes and the Pineal Gland (Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy)

- ↑ Descartes R. Treatise of Man. New York: Prometheus Books; 2003. ISBN 1-59102-090-5

- ↑ Descartes R. "The Passions of the Soul" excerpted from "Philosophy of the Mind", Chalmers, D. New York: Oxford University Press, Inc.; 2002. ISBN-13 978-0-19-514581-6

- ↑ Hollier, D, Against Architecture: The Writings of Georges Bataille, trans. Betsy Wing, MIT, 1989.

- ↑ (p129; Against Architecture)

- ↑ L'Experience interieure, p101 (trans. Leslie A Boldt: The Inner Experience) Albany: SUNY Press

- ↑ Thompson "Fear and Loathing In Las Vegas", p 147, New York: Harper

External links

- BrainMaps at UCDavis pineal%20gland

- NeuroNames hier-280

- Histology at BU 14401loa - "Endocrine System: pineal gland "

- Anatomy Atlases - Microscopic Anatomy, plate 15.296

- Images of Pineal region http://rad.usuhs.edu/medpix/medpix.html?mode=image_finder&action=search&srchstr=pineal&srch_type=all#top

- http://isc.temple.edu/neuroanatomy/lab/atlas/pdhn/

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||