Phishing

In the field of computer security, phishing is the criminally fraudulent process of attempting to acquire sensitive information such as usernames, passwords and credit card details by masquerading as a trustworthy entity in an electronic communication. Communications purporting to be from popular social web sites (Youtube, Facebook, Myspace), auction sites (eBay), online banks (Wells Fargo, Bank of America, Chase), online payment processors (PayPal), or IT Administrators (Yahoo, ISPs, corporate) are commonly used to lure the unsuspecting. Phishing is typically carried out by e-mail or instant messaging,[1] and it often directs users to enter details at a fake website whose URL and look and feel are almost identical to the legitimate one. Even when using SSL with strong cryptography for server authentication it is practically impossible to detect that the website is fake. Phishing is an example of social engineering techniques used to fool users [2], and exploits the poor usability of current web security technologies [3]. Attempts to deal with the growing number of reported phishing incidents include legislation, user training, public awareness, and technical security measures.

A phishing technique was described in detail in 1987, and the first recorded use of the term "phishing" was made in 1996. The term is a variant of fishing,[4] probably influenced by phreaking,[5][6] and alludes to baits used to "catch" financial information and passwords.

Contents |

History and current status of phishing

A phishing technique was described in detail in 1987, in a paper and presentation delivered to the International HP Users Group, Interex.[7] The first recorded mention of the term "phishing" is on the alt.online-service.America-online Usenet newsgroup on January 2, 1996,[8] although the term may have appeared earlier in the print edition of the hacker magazine 2600.[9]

Early phishing on AOL

Phishing on AOL was closely associated with the warez community that exchanged pirated software and the hacking scene that indulged in credit card fraud and other online crimes. After AOL brought in measures in late 1995 to prevent using fake, algorithmically generated credit card numbers to open accounts, AOL crackers resorted to phishing for legitimate accounts.[10] and exploiting AOL.

A phisher might pose as an AOL staff member and send an instant message to a potential victim, asking him to reveal his password.[11] In order to lure the victim into giving up sensitive information the message might include imperatives like "verify your account" or "confirm billing information". Once the victim had revealed the password, the attacker could access and use the victim's account for fraudulent purposes or spamming. Both phishing and warezing on AOL generally required custom-written programs, such as AOHell. Phishing became so prevalent on AOL that they added a line on all instant messages stating: "no one working at AOL will ask for your password or billing information".

After 1997, AOL's policy enforcement with respect to phishing and warez became stricter and forced pirated software off AOL servers. AOL simultaneously developed a system to promptly deactivate accounts involved in phishing, often before the victims could respond. The shutting down of the warez scene on AOL caused most phishers to leave the service, and many phishers—often young teens—grew out of the habit.[12]

Transition from AOL to financial institutions

The capture of AOL account information may have led phishers to misuse credit card information, and to the realization that attacks against online payment systems were feasible. The first known direct attempt against a payment system affected E-gold in June 2001, which was followed up by a "post-911 id check" shortly after the September 11 attacks on the World Trade Center.[13] Both were viewed at the time as failures, but can now be seen as early experiments towards more fruitful attacks against mainstream banks. By 2004, phishing was recognized as a fully industrialized part of the economy of crime: specializations emerged on a global scale that provided components for cash, which were assembled into finished attacks.[14][15]

Recent phishing attempts

Phishers are targeting the customers of banks and online payment services. E-mails, supposedly from the Internal Revenue Service, have been used to glean sensitive data from U.S. taxpayers.[16] While the first such examples were sent indiscriminately in the expectation that some would be received by customers of a given bank or service, recent research has shown that phishers may in principle be able to determine which banks potential victims use, and target bogus e-mails accordingly.[17] Targeted versions of phishing have been termed spear phishing.[18] Several recent phishing attacks have been directed specifically at senior executives and other high profile targets within businesses, and the term whaling has been coined for these kinds of attacks.[19]

Social networking sites are a target of phishing, since the personal details in such sites can be used in identity theft;[20] in late 2006 a computer worm took over pages on MySpace and altered links to direct surfers to websites designed to steal login details.[21] Experiments show a success rate of over 70% for phishing attacks on social networks.[22]

Almost half of phishing thefts in 2006 were committed by groups operating through the Russian Business Network based in St. Petersburg.[23]

Phishing techniques

Link manipulation

Most methods of phishing use some form of technical deception designed to make a link in an e-mail (and the spoofed website it leads to) appear to belong to the spoofed organization. Misspelled URLs or the use of subdomains are common tricks used by phishers. In the following example URL, http://www.yourbank.example.com/, it appears as though the URL will take you to the example section of the yourbank website; actually this URL points to the "yourbank" (i.e. phishing) section of the example website. Another common trick is to make the anchor text for a link appear to be valid, when the link actually goes to the phishers' site. The following example link, Genuine, appears to take you to an article entitled "Genuine"; clicking on it will in fact take you to the article entitled "Deception".

An old method of spoofing used links containing the '@' symbol, originally intended as a way to include a username and password (contrary to the standard).[24] For example, the link http://www.google.com@members.tripod.com/ might deceive a casual observer into believing that it will open a page on www.google.com, whereas it actually directs the browser to a page on members.tripod.com, using a username of www.google.com: the page opens normally, regardless of the username supplied. Such URLs were disabled in Internet Explorer,[25] while Mozilla Firefox[26] and Opera present a warning message and give the option of continuing to the site or cancelling.

A further problem with URLs has been found in the handling of Internationalized domain names (IDN) in web browsers, that might allow visually identical web addresses to lead to different, possibly malicious, websites. Despite the publicity surrounding the flaw, known as IDN spoofing[27] or a homograph attack,[28] Phishers have taken advantage of a similar risk, using open URL redirectors on the websites of trusted organizations to disguise malicious URLs with a trusted domain.[29][30][31]

Filter evasion

Phishers have used images instead of text to make it harder for anti-phishing filters to detect text commonly used in phishing e-mails.[32]

Website forgery

Once a victim visits the phishing website the deception is not over. Some phishing scams use JavaScript commands in order to alter the address bar. [33] This is done either by placing a picture of a legitimate URL over the address bar, or by closing the original address bar and opening a new one with the legitimate URL.[34]

An attacker can even use flaws in a trusted website's own scripts against the victim.[35] These types of attacks (known as cross-site scripting) are particularly problematic, because they direct the user to sign in at their bank or service's own web page, where everything from the web address to the security certificates appears correct. In reality, the link to the website is crafted to carry out the attack, although it is very difficult to spot without specialist knowledge. Just such a flaw was used in 2006 against PayPal.[36]

A Universal Man-in-the-middle Phishing Kit, discovered by RSA Security, provides a simple-to-use interface that allows a phisher to convincingly reproduce websites and capture log-in details entered at the fake site.[37]

To avoid anti-phishing techniques that scan websites for phishing-related text, phishers have begun to use Flash-based websites. These look much like the real website, but hide the text in a multimedia object.[38]

Phone phishing

Not all phishing attacks require a fake website. Messages that claimed to be from a bank told users to dial a phone number regarding problems with their bank accounts.[39] Once the phone number (owned by the phisher, and provided by a Voice over IP service) was dialed, prompts told users to enter their account numbers and PIN. Vishing (voice phishing) sometimes uses fake caller-ID data to give the appearance that calls come from a trusted organization.[40]

Phishing examples

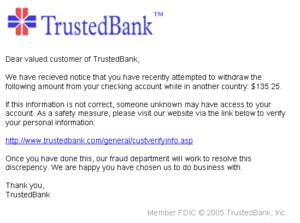

PayPal phishing example

In an example PayPal phish (right), spelling mistakes in the e-mail and the presence of an IP address in the link (visible in the tooltip under the yellow box) are both clues that this is a phishing attempt. Another giveaway is the lack of a personal greeting, although the presence of personal details would not be a guarantee of legitimacy. A legitimate Paypal communication will always greet the user with his or her real name, not just with a generic greeting like, "Dear Accountholder." Other signs that the message is a fraud are misspellings of simple words, bad grammar and the threat of consequences such as account suspension if the recipient fails to comply with the message's requests.

Note that many phishing emails will include, as a real email from PayPal would, large warnings about never giving out your password in case of a phishing attack. Warning users of the possibility of phishing attacks, as well as providing links to sites explaining how to avoid or spot such attacks, are part of what makes the phishing email so deceptive. In this example, the phishing email warns the user that emails from PayPal will never ask for sensitive information. True to its word, it instead invites the user to follow a link to "Verify" their account; this will take them to a further phishing website, engineered to look like PayPal's website, and will there ask for their sensitive information. You can report these phishing emails to PayPal directly. Remember not to use any of the links that your phishing email has provided.

On the RapidShare web host, phishing is common in order to get a premium account, which removes speed caps on downloads, auto-removal of uploads, waits on downloads, and cooldown times between downloads.

Phishers will obtain premium accounts for RapidShare by posting at warez sites with links to files on RapidShare. However, using link aliases like TinyURL, they can disguise the real page's URL, which is hosted somewhere else, and is a look-a-like of RapidShare's "free user or premium user" page. If the victim selects free user, the phisher just passes them along to the real RapidShare site. But if they select premium, then the phishing site records their login before passing them to the download. Thus, the phisher has lifted the premium account information from the victim.

The easiest way to find a RapidShare phishing page is using Mozilla Firefox, right-click on the alias page and select "This Frame" > "Show only this frame." This reveals the real page, and you can see the URL would not be rapidshare.com.

Damage caused by phishing

The damage caused by phishing ranges from denial of access to e-mail to substantial financial loss. This style of identity theft is becoming more popular, because of the readiness with which unsuspecting people often divulge personal information to phishers, including credit card numbers, social security numbers, and mothers' maiden names. There are also fears that identity thieves can add such information to the knowledge they gain simply by accessing public records.[41] Once this information is acquired, the phishers may use a person's details to create fake accounts in a victim's name. They can then ruin the victims' credit, or even deny the victims access to their own accounts.[42]

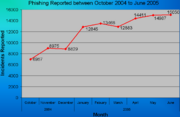

It is estimated that between May 2004 and May 2005, approximately 1.2 million computer users in the United States suffered losses caused by phishing, totaling approximately US$929 million. United States businesses lose an estimated US$2 billion per year as their clients become victims.[43] In 2007 phishing attacks escalated. 3.6 million adults lost US $ 3.2 billion in the 12 months ending in August 2007.[44] The accuracy of these estimates is disputed. In particular the claimed escalation is based on an increase smaller than the survey margin of error, and the dollar amounts may be overstated by a factor of fifty.[45] In the United Kingdom losses from web banking fraud—mostly from phishing—almost doubled to £23.2m in 2005, from £12.2m in 2004,[46] while 1 in 20 computer users claimed to have lost out to phishing in 2005.[47]

The stance adopted by the UK banking body APACS is that "customers must also take sensible precautions ... so that they are not vulnerable to the criminal."[48] Similarly, when the first spate of phishing attacks hit the Irish Republic's banking sector in September 2006, the Bank of Ireland initially refused to cover losses suffered by its customers (and it still insists that its policy is not to do so[49]), although losses to the tune of €11,300 were made good.[50]

Anti-phishing

There are several different techniques to combat phishing, including legislation and technology created specifically to protect against phishing.

Social responses

One strategy for combating phishing is to train people to recognize phishing attempts, and to deal with them. Education can be effective, especially where training provides direct feedback.[51] One newer phishing tactic, which uses phishing e-mails targeted at a specific company, known as spear phishing, has been harnessed to train individuals at various locations, including United States Military Academy at West Point, NY. In a June 2004 experiment with spear phishing, 80% of 500 West Point cadets who were sent a fake e-mail were tricked into revealing personal information.[52]

People can take steps to avoid phishing attempts by slightly modifying their browsing habits. When contacted about an account needing to be "verified" (or any other topic used by phishers), it is a sensible precaution to contact the company from which the e-mail apparently originates to check that the e-mail is legitimate. Alternatively, the address that the individual knows is the company's genuine website can be typed into the address bar of the browser, rather than trusting any hyperlinks in the suspected phishing message.[53]

Nearly all legitimate e-mail messages from companies to their customers contain an item of information that is not readily available to phishers. Some companies, for example PayPal, always address their customers by their username in e-mails, so if an e-mail addresses the recipient in a generic fashion ("Dear PayPal customer") it is likely to be an attempt at phishing.[54] E-mails from banks and credit card companies often include partial account numbers. However, recent research[55] has shown that the public do not typically distinguish between the first few digits and the last few digits of an account number—a significant problem since the first few digits are often the same for all clients of a financial institution. People can be trained to have their suspicion aroused if the message does not contain any specific personal information. Phishing attempts in early 2006, however, used personalized information, which makes it unsafe to assume that the presence of personal information alone guarantees that a message is legitimate.[56] Furthermore, another recent study concluded in part that the presence of personal information does not significantly affect the success rate of phishing attacks,[57] which suggests that most people do not pay attention to such details.

The Anti-Phishing Working Group, an industry and law enforcement association, has suggested that conventional phishing techniques could become obsolete in the future as people are increasingly aware of the social engineering techniques used by phishers.[58] They predict that pharming and other uses of malware will become more common tools for stealing information.

Everyone can help educate the public by encouraging safe practices, and by avoiding dangerous ones. Unfortunately, even well-known players are known to incite users to hazardous behaviour, e.g. by requesting their users to reveal their passwords for third party services, such as email. [59]

Technical responses

Anti-phishing measures have been implemented as features embedded in browsers, as extensions or toolbars for browsers, and as part of website login procedures. The following are some of the main approaches to the problem.

Helping to identify legitimate websites

Most websites targeted for phishing are secure websites, meaning that SSL with strong cryptography is used for server authentication, where the website's URL is used as identifier. In theory it should be possible for the SSL authentication to be used to confirm the site to the user, and this was SSL v2's design requirement and the meta of secure browsing. But in practice, this is easy to trick.

The superficial flaw is that the browser's security user interface (UI) is insufficient to deal with today's strong threats. There are three parts to secure authentication using TLS and certificates: indicating that the connection is in authenticated mode, indicating which site the user is connected to, and indicating which authority says it is this site. All three are necessary for authentication, and need to be confirmed by/to the user.

Secure Connection. The standard display for secure browsing from the mid-1990s to mid-2000s was the padlock, which is easily missed by the user. Mozilla fielded a yellow URL bar in 2005 as a better indication of the secure connection. Unfortunately, this innovation was then reversed due to the EV certificates, which replaced certain high-value certificates with a green display, and other certificates with a white display.

Which Site. The user is expected to confirm that the domain name in the browser's URL bar was in fact where they intended to go. URLs can be too complex to be easily parsed. Users often do not know or recognise the URL of the legitimate sites they intend to connect to, so that the authentication becomes meaningless [3]. A condition for meaningful server authentication is to have a server identifier that is meaningful to the user; many ecommerce sites will change the domain names within their overall set of websites, adding to the opportunity for confusion. Simply displaying the domain name for the visited website [60] as some some anti-phishing toolbars do is not sufficient.

An alternate approach is the petname extension for Firefox which lets users type in their own labels for websites, so they can later recognize when they have returned to the site. If the site is not recognised, then the software may either warn the user or block the site outright. This represents user-centric identity management of server identities [61]. Some suggest that a graphical image selected by the user is better than a petname[62].

With the advent of EV certificates, browsers now typically display the organisation's name in green, which is much more visible and is hopefully more consistent with the user's expectations. Unfortunately, browser vendors have chosen to limit this prominent display only to EV certificates, leaving the user to fend for himself with all other certificates.

Who is the Authority. The browser needs to state who the authority is that makes the claim of who the user is connected to. At the simplest level, no authority is stated, and therefore the browser is the authority, as far as the user is concerned. The browser vendors take on this responsibility by controlling a root list of acceptable CAs. This is the current standard practice.

The problem with this is that not all certification authorities (CAs) employ equally good nor applicable checking, regardless of attempts by browser vendors to control the quality. Nor do all CAs subscribe to the same model and concept that certificates are only about authenticating ecommerce organisations. Certificate Manufacturing is the name given to low-value certificates that are delivered on a credit card and an email confirmation; both of these are easily perverted by fraudsters. Hence, a high-value site may be easily spoofed by a valid certificate provided by another CA. This could be because the CA is in another part of the world, and is unfamiliar with high-value ecommerce sites, or it could be that no care is taken at all. As the CA is only charged with protecting its own customers, and not the customers of other CAs, this flaw is inherent in the model.

The solution to this is that the browser should show, and the user should be familiar with, the name of the authority. This presents the CA as a brand, and allows the user to learn the handful of CAs that she is likely to come into contact within her country and her sector. The use of brand is also critical to providing the CA with an incentive to improve their checking, as the user will learn the brand and demand good checking for high-value sites.

This solution was first put into practice in early IE7 versions, when displaying EV certificates [63]. In that display, the issuing CA is displayed. (Need to update comment to modern IE7 display and IE8 betas.) This was an isolated case, however. There is resistance to CAs being branded on the chrome, resulting in a fallback to the simplest level above: the browser is the user's authority.

Fundamental Flaws in the Security Model of Secure Browsing

Experiments to improve the security UI have resulted in benefits, but have also exposed fundamental flaws in the security model. The underlying causes for the failure of the SSL authentication to be employed properly in secure browsing are many and intertwined.

Security before threat. Because secure browsing was put into place before any threat was evident, the security display lost out in the "real estate wars" of the early browsers. The original design of Netscape's browser included a prominent display of the name of the site and the CA's name, but these were dropped in the first release (need ref). Users are now highly experienced in not checking security information at all.

Click-thru Syndrome. However, warnings to poorly configured sites continued, and were not down-graded. If a certificate had an error in it (mismatched domain name, expiry), then the browser would commonly launch a popup to warn the user. As the reason was generally misconfiguration, the users learned to bypass the warnings, and now, users are accustomed to treat all warnings with the same disdain, resulting in Click-thru syndrome. For example, Firefox 3 has a 4-click process for adding an exception, but it has been shown to be ignored by an experienced user in a real case of MITM. Even today, as the vast majority of warnings will be for misconfigurations not real MITMs, it is hard to see how click-thru syndrome will ever be avoided.

Lack of Interest. Another underlying factor is the lack of support for virtual hosting. The specific causes are a lack of support for Server Name Indication in TLS webservers, and the expense and inconvenience of acquiring certificates. The result is that the use of authentication is too rare to be anything but a special case. This has caused a general lack of knowledge and resources in authentication within TLS, which in turn has meant that the attempts by browser vendors to upgrade their security UIs have been slow and lacklustre.

Lateral communications. The security model for secure browser includes many participants: user, browser vendor, developers, CA, auditor, webserver vendor, ecommerce site, regulators (e.g., FDIC), and security standards committees. There is a lack of communication between different groups that are committed to the security model. E.g., although the understanding of authentication is strong at the protocol level of the IETF committees, this message does not reach the UI groups. Webserver vendors do not prioritise the Server Name Indication (TLS/SNI) fix, not seeing it as a security fix but instead a new feature. In practice, all participants look to the others as the source of the failures leading to phishing, hence the local fixes are not prioritised.

Matters improved slightly with the CAB Forum, as that group includes browser vendors, auditors and CAs. But the group did not start out in an open fashion, and the result suffered from commercial interests of the first players, as well as a lack of parity between the participants. Even today, CAB forum is not open, and does not include representation from small CAs, end-users, ecommerce owners, etc.

Standards gridlock. Vendors commit to standards, which results in an outsourcing effect when it comes to security. Although there have been many and good experiments in improving the security UI, these have not been adopted because they are not standard, or clash with the standards. Threat models can re-invent themselves in around a month; Security standards take around 10 years to adjust.

Venerable CA Model. Control mechanisms employed by the browser vendors over the CAs have not been substantially updated; the threat model has. The control and quality process over CAs is insufficiently tuned to the protection of users and the addressing of actual and current threats. Audit processes are in great need of updating. The recent EV Guidelines documented the current model in greater detail, and established a good benchmark, but did not push for any substantial changes to be made.

Browsers alerting users to fraudulent websites

Another popular approach to fighting phishing is to maintain a list of known phishing sites and to check websites against the list. Microsoft's IE7 browser, Mozilla Firefox 2.0, Safari 3.2, and Opera all contain this type of anti-phishing measure.[64][65][66][67] Firefox 2 used Google anti-phishing software. Opera 9.1 uses live blacklists from PhishTank and GeoTrust, as well as live whitelists from GeoTrust. Some implementations of this approach send the visited URLs to a central service to be checked, which has raised concerns about privacy.[68] According to a report by Mozilla in late 2006, Firefox 2 was found to be more effective than Internet Explorer 7 at detecting fraudulent sites in a study by an independent software testing company.[69]

An approach introduced in mid-2006 involves switching to a special DNS service that filters out known phishing domains: this will work with any browser,[70] and is similar in principle to using a hosts file to block web adverts.

To mitigate the problem of phishing sites impersonating a victim site by embedding its images (such as logos), several site owners have altered the images to send a message to the visitor that a site may be fraudulent. The image may be moved to a new filename and the original permanently replaced, or a server can detect that the image was not requested as part of normal browsing, and instead send a warning image.[71][72]

Augmenting password logins

The Bank of America's website[73][74] is one of several that ask users to select a personal image, and display this user-selected image with any forms that request a password. Users of the bank's online services are instructed to enter a password only when they see the image they selected. However, a recent study suggests few users refrain from entering their password when images are absent.[75][76] In addition, this feature (like other forms of two-factor authentication) is susceptible to other attacks, such as those suffered by Scandinavian bank Nordea in late 2005,[77] and Citibank in 2006.[78]

Security skins[79][80] are a related technique that involves overlaying a user-selected image onto the login form as a visual cue that the form is legitimate. Unlike the website-based image schemes, however, the image itself is shared only between the user and the browser, and not between the user and the website. The scheme also relies on a mutual authentication protocol, which makes it less vulnerable to attacks that affect user-only authentication schemes.

Eliminating phishing mail

Specialized spam filters can reduce the number of phishing e-mails that reach their addressees' inboxes. These approaches rely on machine learning and natural language processing approaches to classify phishing e-mails.[81][82]

Monitoring and takedown

Several companies offer banks and other organizations likely to suffer from phishing scams round-the-clock services to monitor, analyze and assist in shutting down phishing websites.[83] Individuals can contribute by reporting phishing to both volunteer and industry groups,[84] such as PhishTank.[85]

Legal responses

On January 26, 2004, the U.S. Federal Trade Commission filed the first lawsuit against a suspected phisher. The defendant, a Californian teenager, allegedly created a webpage designed to look like the America Online website, and used it to steal credit card information.[86] Other countries have followed this lead by tracing and arresting phishers. A phishing kingpin, Valdir Paulo de Almeida, was arrested in Brazil for leading one of the largest phishing crime rings, which in two years stole between US$18 million and US$37 million.[87] UK authorities jailed two men in June 2005 for their role in a phishing scam,[88] in a case connected to the U.S. Secret Service Operation Firewall, which targeted notorious "carder" websites.[89] In 2006 eight people were arrested by Japanese police on suspicion of phishing fraud by creating bogus Yahoo Japan Web sites, netting themselves 100 million yen ($870,000 USD).[90] The arrests continued in 2006 with the FBI Operation Cardkeeper detaining a gang of sixteen in the U.S. and Europe.[91]

In the United States, Senator Patrick Leahy introduced the Anti-Phishing Act of 2005 in Congress on March 1, 2005. This bill, if it had been enacted into law, would have subjected criminals who created fake web sites and sent bogus e-mails in order to defraud consumers to fines of up to $250,000 and prison terms of up to five years.[92] The UK strengthened its legal arsenal against phishing with the Fraud Act 2006,[93] which introduces a general offence of fraud that can carry up to a ten year prison sentence, and prohibits the development or possession of phishing kits with intent to commit fraud.[94]

Companies have also joined the effort to crack down on phishing. On March 31, 2005, Microsoft filed 117 federal lawsuits in the U.S. District Court for the Western District of Washington. The lawsuits accuse "John Doe" defendants of obtaining passwords and confidential information. March 2005 also saw a partnership between Microsoft and the Australian government teaching law enforcement officials how to combat various cyber crimes, including phishing.[95] Microsoft announced a planned further 100 lawsuits outside the U.S. in March 2006,[96] followed by the commencement, as of November 2006, of 129 lawsuits mixing criminal and civil actions.[97] AOL reinforced its efforts against phishing[98] in early 2006 with three lawsuits[99] seeking a total of $18 million USD under the 2005 amendments to the Virginia Computer Crimes Act,[100][101] and Earthlink has joined in by helping to identify six men subsequently charged with phishing fraud in Connecticut.[102]

In January 2007, Jeffrey Brett Goodin of California became the first defendant convicted by a jury under the provisions of the CAN-SPAM Act of 2003. He was found guilty of sending thousands of e-mails to America Online users, while posing as AOL's billing department, which prompted customers to submit personal and credit card information. Facing a possible 101 years in prison for the CAN-SPAM violation and ten other counts including wire fraud, the unauthorized use of credit cards, and the misuse of AOL's trademark, he was sentenced to serve 70 months. Goodin had been in custody since failing to appear for an earlier court hearing and began serving his prison term immediately.[103][104][105][106]

See also

- Anti-phishing software

- Computer insecurity

- Confidence trick

- Dancing pigs

- Defensive computing

- DomainKeys

- E-mail spoofing

- Pharming

- Rock Phish Kit

- Social engineering

- Vishing

References

- ↑ Tan, Koon. "Phishing and Spamming via IM (SPIM)". Internet Storm Center. Retrieved on December 5, 2006.

- ↑ Microsoft Corporation. "What is social engineering?". Retrieved on August 22, 2007.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Jøsang, Audun et al.. "Security Usability Principles for Vulnerability Analysis and Risk Assessment." (PDF). Proceedings of the Annual Computer Security Applications Conference 2007 (ACSAC'07).

- ↑ "Spam Slayer: Do You Speak Spam?". PCWorld.com. Retrieved on August 16, 2006.

- ↑ ""phishing, n." OED Online, March 2006, Oxford University Press.". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Retrieved on August 9, 2006.

- ↑ "Phishing". Language Log, September 22, 2004. Retrieved on August 9, 2006.

- ↑ Felix, Jerry and Hauck, Chris (September 1987). "System Security: A Hacker's Perspective". 1987 Interex Proceedings 1: 6.

- ↑ ""phish, v." OED Online, March 2006, Oxford University Press.". Oxford English Dictionary Online. Retrieved on August 9, 2006.

- ↑ Ollmann, Gunter. "The Phishing Guide: Understanding and Preventing Phishing Attacks". Technical Info. Retrieved on July 10, 2006.

- ↑ "Phishing". Word Spy. Retrieved on September 28, 2006.

- ↑ Stutz, Michael (January 29, 1998). "AOL: A Cracker's Paradise?", Wired News.

- ↑ "History of AOL Warez".

- ↑ "GP4.3 - Growth and Fraud - Case #3 - Phishing". Financial Cryptography (December 30, 2005).

- ↑ "In 2005, Organized Crime Will Back Phishers". IT Management (December 23, 2004).

- ↑ "The economy of phishing: A survey of the operations of the phishing market". First Monday (September 2005).

- ↑ "Suspicious e-Mails and Identity Theft". Internal Revenue Service. Retrieved on July 5, 2006.

- ↑ "Phishing for Clues", Indiana University Bloomington (September 15, 2005).

- ↑ "What is spear phishing?". Microsoft Security At Home. Retrieved on July 10, 2006.

- ↑ Goodin, Dan (April 17, 2008). "Fake subpoenas harpoon 2,100 corporate fat cats", The Register.

- ↑ Kirk, Jeremy (June 2, 2006). "Phishing Scam Takes Aim at MySpace.com", IDG Network.

- ↑ "Malicious Website / Malicious Code: MySpace XSS QuickTime Worm". Websense Security Labs. Retrieved on December 5, 2006.

- ↑ Tom Jagatic and Nathan Johnson and Markus Jakobsson and Filippo Menczer. "Social Phishing" (PDF). To appear in the CACM (October 2007). Retrieved on June 3, 2006.

- ↑ Shadowy Russian Firm Seen as Conduit for Cybercrime, by Brian Krebs, Washington post, October 13, 2007

- ↑ Berners-Lee, Tim. "Uniform Resource Locators (URL)". IETF Network Working Group. Retrieved on January 28, 2006.

- ↑ Microsoft. "A security update is available that modifies the default behavior of Internet Explorer for handling user information in HTTP and in HTTPS URLs". Microsoft Knowledgebase. Retrieved on August 28, 2005.

- ↑ Fisher, Darin. "Warn when HTTP URL auth information isn't necessary or when it's provided". Bugzilla. Retrieved on August 28, 2005.

- ↑ Johanson, Eric. "The State of Homograph Attacks Rev1.1". The Shmoo Group. Retrieved on August 11, 2005.

- ↑ Evgeniy Gabrilovich and Alex Gontmakher (February 2002). "The Homograph Attack" (PDF). Communications of the ACM 45(2): 128. http://www.cs.technion.ac.il/~gabr/papers/homograph_full.pdf.

- ↑ Leyden, John (August 15, 2006). "Barclays scripting SNAFU exploited by phishers", The Register.

- ↑ Levine, Jason. "Goin' phishing with eBay". Q Daily News. Retrieved on December 14, 2006.

- ↑ Leyden, John (December 12, 2007). "Cybercrooks lurk in shadows of big-name websites", The Register.

- ↑ Mutton, Paul. "Fraudsters seek to make phishing sites undetectable by content filters". Netcraft. Retrieved on July 10, 2006.

- ↑ Mutton, Paul. "Phishing Web Site Methods". FraudWatch International. Retrieved on December 14, 2006.

- ↑ "Phishing con hijacks browser bar", BBC News (April 8, 2004).

- ↑ Krebs, Brian. "Flaws in Financial Sites Aid Scammers". Security Fix. Retrieved on June 28, 2006.

- ↑ Mutton, Paul. "PayPal Security Flaw allows Identity Theft". Netcraft. Retrieved on June 19, 2006.

- ↑ Hoffman, Patrick (January 10, 2007). "RSA Catches Financial Phishing Kit", eWeek.

- ↑ Miller, Rich. "Phishing Attacks Continue to Grow in Sophistication". Netcraft. Retrieved on December 19, 2007.

- ↑ Gonsalves, Antone (April 25, 2006). "Phishers Snare Victims With VoIP", Techweb.

- ↑ "Identity thieves take advantage of VoIP", Silicon.com (March 21, 2005).

- ↑ Virgil Griffith and Markus Jakobsson. "Messin' with Texas, Deriving Mother's Maiden Names Using Public Records" (PDF). ACNS '05. Retrieved on July 7, 2006.

- ↑ Krebs, Brian (November 18, 2004). "Phishing Schemes Scar Victims", washingtonpost.com.

- ↑ Kerstein, Paul (July 19, 2005). "How Can We Stop Phishing and Pharming Scams?", CSO.

- ↑ McCall, Tom (December 17, 2007). "Gartner Survey Shows Phishing Attacks Escalated in 2007; More than $3 Billion Lost to These Attacks", Gartner.

- ↑ "A Profitless Endeavor: Phishing as Tragedy of the Commons" (PDF). Microsoft. Retrieved on November 15, 2008.

- ↑ "UK phishing fraud losses double", Finextra (March 7, 2006).

- ↑ Richardson, Tim (May 3, 2005). "Brits fall prey to phishing", The Register.

- ↑ Miller, Rich. "Bank, Customers Spar Over Phishing Losses". Netcraft. Retrieved on December 14, 2006.

- ↑ Latest News

- ↑ Bank of Ireland agrees to phishing refunds – vnunet.com

- ↑ Ponnurangam Kumaraguru, Yong Woo Rhee, Alessandro Acquisti, Lorrie Cranor, Jason Hong and Elizabeth Nunge (November 2006). "Protecting People from Phishing: The Design and Evaluation of an Embedded Training Email System" (PDF). Technical Report CMU-CyLab-06-017, CyLab, Carnegie Mellon University.. Retrieved on November 14, 2006.

- ↑ Bank, David (August 17, 2005). "'Spear Phishing' Tests Educate People About Online Scams", The Wall Street Journal.

- ↑ "Anti-Phishing Tips You Should Not Follow". HexView. Retrieved on June 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Protect Yourself from Fraudulent Emails". PayPal. Retrieved on July 7, 2006.

- ↑ Markus Jakobsson, Alex Tsow, Ankur Shah, Eli Blevis, Youn-kyung Lim.. "What Instills Trust? A Qualitative Study of Phishing." (PDF). USEC '06.

- ↑ Zeltser, Lenny (March 17, 2006). "Phishing Messages May Include Highly-Personalized Information", The SANS Institute.

- ↑ Markus Jakobsson and Jacob Ratkiewicz. "Designing Ethical Phishing Experiments". WWW '06.

- ↑ Kawamoto, Dawn (August 4, 2005). "Faced with a rise in so-called pharming and crimeware attacks, the Anti-Phishing Working Group will expand its charter to include these emerging threats.", ZDNet India.

- ↑ "Social networking site teaches insecure password practices". blog.anta.net. 2008-11-09. ISSN 1797-1993. http://blog.anta.net/2008/11/09/social-networking-site-teaches-insecure-password-practices/. Retrieved on 2008-11-09.

- ↑ Brandt, Andrew. "Privacy Watch: Protect Yourself With an Antiphishing Toolbar". PC World – Privacy Watch. Retrieved on September 25, 2006.

- ↑ Jøsangm Audun and Pope, Simon. "User Centric Identity Management" (PDF). Proceedings of AusCERT 2005.

- ↑ "Phishing - What it is and How it Will Eventually be Dealt With" by Ian Grigg 2005

- ↑ "Brand matters (IE7, Skype, Vonage, Mozilla)" Ian Grigg

- ↑ Franco, Rob. "Better Website Identification and Extended Validation Certificates in IE7 and Other Browsers". IEBlog. Retrieved on May 20, 2006.

- ↑ "Bon Echo Anti-Phishing". Mozilla. Retrieved on June 2, 2006.

- ↑ "Safari 3.2 finally gains phishing protection". Ars Technica (November 13, 2008). Retrieved on November 15, 2008.

- ↑ "Gone Phishing: Evaluating Anti-Phishing Tools for Windows", 3Sharp (September 27, 2006). Retrieved on 2006-10-20.

- ↑ "Two Things That Bother Me About Google’s New Firefox Extension". Nitesh Dhanjani on O'Reilly ONLamp. Retrieved on July 1, 2007.

- ↑ "Firefox 2 Phishing Protection Effectiveness Testing". Retrieved on January 23, 2007.

- ↑ Higgins, Kelly Jackson. "DNS Gets Anti-Phishing Hook". Dark Reading. Retrieved on October 8, 2006.

- ↑ Krebs, Brian (August 31, 2006). "Using Images to Fight Phishing", Security Fix.

- ↑ Seltzer, Larry (August 2, 2004). "Spotting Phish and Phighting Back", eWeek.

- ↑ Bank of America. "How Bank of America SiteKey Works For Online Banking Security". Retrieved on January 23, 2007.

- ↑ Brubaker, Bill (July 14, 2005). "Bank of America Personalizes Cyber-Security", Washington Post.

- ↑ Stone, Brad (February 5, 2007). "Study Finds Web Antifraud Measure Ineffective". New York Times. Retrieved on February 5, 2007.

- ↑ Stuart Schechter, Rachna Dhamija, Andy Ozment, Ian Fischer (May 2007). "The Emperor's New Security Indicators: An evaluation of website authentication and the effect of role playing on usability studies" (PDF). IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy, May 2007. Retrieved on February 5, 2007.

- ↑ "Phishers target Nordea's one-time password system", Finextra (October 12, 2005).

- ↑ Krebs, Brian (July 10, 2006). "Citibank Phish Spoofs 2-Factor Authentication", Security Fix.

- ↑ Schneier, Bruce. "Security Skins". Schneier on Security. Retrieved on December 3, 2006.

- ↑ Rachna Dhamija, J.D. Tygar (July 2005). "The Battle Against Phishing: Dynamic Security Skins" (PDF). Symposium On Usable Privacy and Security (SOUPS) 2005. Retrieved on February 5, 2007.

- ↑ Madhusudhanan Chandrasekaran, Krishnan Narayanan, Shambhu Upadhyaya (March 2006). "Phishing E-mail Detection Based on Structural Properties" (PDF). NYS Cyber Security Symposium.

- ↑ Ian Fette, Norman Sadeh, Anthony Tomasic (June 2006). "Learning to Detect Phishing Emails" (PDF). Carnegie Mellon University Technical Report CMU-ISRI-06-112.

- ↑ "Anti-Phishing Working Group: Vendor Solutions". Anti-Phishing Working Group. Retrieved on July 6, 2006.

- ↑ McMillan, Robert (March 28, 2006). "New sites let users find and report phishing", LinuxWorld.

- ↑ Schneier, Bruce (2006-10-05). "PhishTank". Schneier on Security. Retrieved on 2007-12-07.

- ↑ Legon, Jeordan (January 26, 2004). "'Phishing' scams reel in your identity", CNN.

- ↑ Leyden, John (March 21, 2005). "Brazilian cops net 'phishing kingpin'", The Register.

- ↑ Roberts, Paul (June 27, 2005). "UK Phishers Caught, Packed Away", eWEEK.

- ↑ "Nineteen Individuals Indicted in Internet 'Carding' Conspiracy". Retrieved on November 20, 2005.

- ↑ "8 held over suspected phishing fraud", The Daily Yomiuri (May 31, 2006).

- ↑ "Phishing gang arrested in USA and Eastern Europe after FBI investigation". Retrieved on December 14, 2006.

- ↑ "Phishers Would Face 5 Years Under New Bill", Information Week (March 2, 2005).

- ↑ "Fraud Act 2006". Retrieved on December 14, 2006.

- ↑ "Prison terms for phishing fraudsters", The Register (November 14, 2006).

- ↑ "Microsoft Partners with Australian Law Enforcement Agencies to Combat Cyber Crime". Retrieved on August 24, 2005.

- ↑ Espiner, Tom (March 20, 2006). "Microsoft launches legal assault on phishers", ZDNet.

- ↑ Leyden, John (November 23, 2006). "MS reels in a few stray phish", The Register.

- ↑ "A History of Leadership - 2006".

- ↑ "AOL Takes Fight Against Identity Theft To Court, Files Lawsuits Against Three Major Phishing Gangs". Retrieved on March 8, 2006.

- ↑ "HB 2471 Computer Crimes Act; changes in provisions, penalty.". Retrieved on March 8, 2006.

- ↑ Brulliard, Karin (April 10, 2005). "Va. Lawmakers Aim to Hook Cyberscammers", Washington Post.

- ↑ "Earthlink evidence helps slam the door on phisher site spam ring". Retrieved on December 14, 2006.

- ↑ Prince, Brian (January 18, 2007). "Man Found Guilty of Targeting AOL Customers in Phishing Scam", PCMag.com.

- ↑ Leyden, John (January 17, 2007). "AOL phishing fraudster found guilty", The Register.

- ↑ Leyden, John (June 13, 2007). "AOL phisher nets six years' imprisonment", The Register.

- ↑ Gaudin, Sharon (June 12, 2007). "California Man Gets 6-Year Sentence For Phishing", InformationWeek.

External links

- Anti-Phishing Working Group

- Bank Safe Online – Advice to UK consumers

- Center for Identity Management and Information Protection – Utica College

- E-scams and Warnings Update – Federal Bureau of Investigation

- Global Phishing Summary Report – Real-time database of phishing activity.

- How the bad guys actually operate – Ha.ckers.org Application Security Lab

- Plugging the "phishing" hole: legislation versus technology – Duke Law & Technology Review

- Know Your Enemy: Phishing – Honeynet project case study

- SecurityFocus – forensic examination of a phishing attack.

- The Phishing Guide: Understanding and Preventing Phishing Attacks – TechnicalInfo.net

- Anti Phising Phil– game helping users to identify phising attempts

|

||||||||||||||||||||||