Persian people

- • "Persians" redirects here. For the Athenian tragedy, see The Persians.

Rumi • Al-Khwarizmi • Omar Khayyám • Amir Kabir

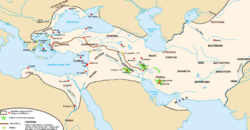

Persian identity, at least in terms of language, is traced to the ancient Indo-Iranians (Aryans), who arrived in parts of Greater Iran circa 2000-1500 BCE. Starting around 550 BCE, from the province of Fars in Iran, the ancient Persians spread their language and culture to other parts of the Iranian plateau through conquest and assimilated local Iranic and non-Iranic groups over time. This process of assimilation continued in the face of Greek, Arab, Mongol and Turkic invasions and continued right up to Islamic times.[1][2]

Numerous dialects and regional identities emerged over time, while a Persian orientation fully manifested itself in Iran and Afghanistan by the 20th century, mirroring developments in post-Ottoman Turkey, the Arab world and Europe. With the disintegration of the final Persian Empires of the Afsharid and Qajar dynasties, Afghanistan and territories in the Caucasus,[3] and Central Asia either became independent from Iran or incorporated into the Russian Empire.

The Persian peoples emerged as an eclectic collection of groups with the Persian language being the main shared legacy. Diverse populations in Central Asia, such as the Hazaras show traces of Mongol ancestry, while Persians along the border with Iraq have ties to Iraqi Arab Shia culture. Regional dialects spoken by Tajiks in Afghanistan show an ancient affinity with the dialects spoken in Khurasan and Tabaristan. As Persian was the lingua franca of the Iranian plateau (the highlands between Iraq and the Indus) it has come to be used by numerous groups as a second language including Turkic and Arab groups. While most Persians in Iran adhere to Shia Islam, those to the east remain followers of Sunni Islam. Small groups of Persians continue to follow the pre-Islamic faith of Zoroastrianism in Iran, and in Pakistan and India where usage of the Persian language is largely for liturgical purposes.

While a categorization of a 'Persian' ethnic group persists in the West, Persians have generally been a pan-national group often comprised of regional peoples who rarely refer to themselves as 'Persians' and sometimes use the term 'Iranian' instead. The synonymous usage of Iranian and Persian persisted over the centuries despite the varied meanings of Iranian, which includes different but related languages and ethnic groups. As a pan-national group, defining Persians as an ethnic group, at least in terms used in the West, is problematic since Persians are as varied as groups such as Arabs.

Contents |

Terminology

The term Persia was adopted by all western languages through the Greeks and was used as an official name for Iran by the West until 1935. Due to that label, all Iranians were considered Persian. Also, many others who embraced the Persian language and culture are also often referred to as Persian as a part of Persian civilization (culturally and/or linguistically).

Ancient

The first known written record about Persians is from an Assyrian inscription of the 834 BCE, which mentions both Parsua (Persians) and Muddai (Medes).[4][5] The term used by Assyrians, Parsua, was a general designation to refer to southwestern Iranian tribes (who referred to themselves as Aryans as an ethnic designation or showing the nobility). Such words were taken from the Old Persian Pârsâ. The Greeks (who tended earlier to use names related to "Median") began in the fifth century to use adjectives such as Perses, Persica or Persis for Cyrus the Great's empire (a word meaning "country" being understood)[6], which is where the word Persian in English comes from. In the later parts of the Bible, where this kingdom is frequently mentioned (Books of Esther, Daniel, Ezra and Nehemya), it is called "Paras" (Hebrew פרס), or sometimes "Paras ve Madai" (פרס ומדי) i.e. "Persia and Media".

One of the roots of creative simulations during the Parthian Empire was the Achaemenid Empire. Courtiers spoke Persian and used the Pahlavi script.[7] During the Sassanid Empire the intermingling of Persians, Medes, Parthians and indigeneous people of Iran, including the Elamites gained more ground and a homogeneous Iranian identity was created to the extent that all were just called Iranians/Persians irrespective of clannish affiliations and regional linguistic or dialectical alterities. The Elamite language may have survived as late as the early Islamic period. Ibn al-Nadim among other Arab medieval historians, for instance, wrote that "The Iranian languages are Fahlavi (Pahlavi), Dari, Khuzi, Persian and Suryani", and Ibn Moqaffa noted that Khuzi was the unofficial language of the royalty of Persia, "Khuz" being the corrupted name for Elam. However the Elamite identity might have vanished already.

Islamic era

The term Persian continued to refer to various Iranic people including speakers of Chorasmian Language[8], old Tabari language[9], Old Azari language [10], Laki and Kurdish speakers[11].

The Arab historian Abu al-Hasan Ali ibn al-Husayn Al-Masudi (896-956) also refers to various Persian dialects and the speakers of these various Persian dialects as Persian. While considering modern Persian (Dari) to be one of these dialects, he also mentions Pahlavi and Old Azari, as well as other Persian languages. Al-Masudi states:[12]:

The Persians are a people whose borders are the Mahat Mountains and Azarbaijan up to Armenia and Arran, and Bayleqan and Darband, and Ray and Tabaristan and Masqat and Shabaran and Jorjan and Abarshahr, and that is Nishabur, and Herat and Marv and other places in land of Khorasan, and Sejistan and Kerman and Fars and Ahvaz...All these lands were once one kingdom with one sovereign and one language...although the language differed slightly. The language, however, is one, in that its letters are written the same way and used the same way in composition. There are, then, different languages such as Pahlavi, Dari, Azari, as well as other Persian languages.

Modern era

The name "Persia" was the "official" name of Iran in the Western world before 1935, but Persian people inside their country since the Sassanid period (226–651 A.D.) have called it "Iran". Accordingly the term "Persian" was used in the Western world as the people inhabiting Iran; for instance, Ramsay MacDonald (1866-1937), the Prime-Minister of the United Kingdom, and the British ambassador in Iran, Percy Loraine, used Persian and Persian people to talk about the Iranian people and government.[13] On 21 March, 1935, the ruler of the country, Reza Shah Pahlavi, issued a decree asking foreign delegates to use the term Iran in formal correspondence. From then on "Iranian" and "Persian" was applied interchangeably to the population of Iran. It is still historically being used to designate some Iranian people living in Greater Iran.[14][15][16]

Sub-groups

Persians can be found in Iran, Afghanistan, Tajikistan, Uzbekistan, Xinjiang province of China and Northern Pakistan. Like the Persians of Iran (Western Persians), the Tajiks (Eastern Persians) are descendants of various Iranian peoples, including Persians from Iran, as well as numerous invaders. Tajiks and Farsiwan have a particular affinity with Persians in neighboring Khorasan due to historical interaction some stemming from the Islamic period.

Other smaller groups include the Qizilbash of Afghanistan and Pakistan who are related to the Farsiwan and Azerbaijanis. In the Caucasus, the Tats are concentrated in Azerbaijan, Armenia, and Russian Dagestan and their origins are traced to Sassanid merchants who settled in the region. Parsis, a Zoroastrian sect of western India and Pakistan, centered around Gujarat and Mumbai, are also largely descended from Persian Zoroastrians. The Iranis, another small community in western India, are descended from more recent Persian Zoroastrian immigrants. In addition, the Hazara and Aimaq are ethnic groups of partial Persianized Mongol and Turkic origin.

History

- See also: Persian Empire, History of Iran, History of Tajikistan, History of Uzbekistan, and History of Central Asia

The Persians are descendents of the Aryan (Indo-Iranian) tribes that began migrating from Central Asia into what is now Iran in the second millennium BCE.[17][18][19] The Persian language and other Iranian tongues emerged as these Aryan tribes split up into two major groups, the Persians and the Medes, and intermarried with minority peoples indigenous to the Iranian plateau such as the Elamites.[20][21] The first mention of the Persians dates to the 9th century BCE, when they appear as the Parsu in Assyrian sources, as a people living at the southeastern shores of Lake Urmia.

The ancient Persians from the province of Pars became the rulers of a large empire under the Achaemenid dynasty (Hakhamaneshiyan) in the sixth century BCE, reuniting with the tribes and other provinces of the ancient Iranian plateau and forming the Persian Empire. Over the centuries Persia was ruled by various dynasties; some of them were ethnic Iranians including the Achaemenids, Parthians (Ashkanian), Sassanids (Sassanian), Buwayhids and Samanids, and some of them were not, such as the Seleucids, Ummayyads, Abbasids, and Seljuk Turks.

The founding dynasty of the empire, the Achaemenids, and later the Sassanids, were from the southern region of Iran, Pars. The latter Parthian dynasty arose from the north. However, according to archaeological evidence found in modern day Iran in the form of cuneiforms that go back to the Achaemenid era, it is evident that the native name of Parsa (Persia) had been applied to Iran from its birth.[22][23]

Language

The Persian language is one of the world's oldest languages still in use today, and is known to have one of the most powerful literary traditions, with formidable Persian poets like Ferdowsi, Hafez, Khayyam, Attar, Saadi, Nezami, Roudaki, Rumi and Sanai. By native speakers as well as in Urdu, Bengali, Turkish, Arabic and other neighboring languages, it is called Fārsī, and additionally Dari or Tajiki in the eastern parts of Greater Iran.

"Persian" has been historically referred to some Iranian languages, however what is called today as Persian language is part of the Western group of the Iranian languages branch of the Indo-European language family. Today, speakers of the western dialect of Persian form the majority in Iran. The Eastern dialect, also called Dari or Tajiki, forms majorities in Tajikistan, and Afghanistan,[24] and a large minority in Uzbekistan. Smaller groups of Persian-speakers are found in Pakistan, western China (Xinjiang), as well as in the UAE, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman and Azerbaijan.

Religion

The Persian civilization spawned three major religions: Zoroastrianism, Manichaeism, which heavily influenced Saint Augustine before he turned to Christianity, and the Bahá'í Faith. Another religion that arose from ancient Iran is Mazdakism, which has been dubbed the first communistic ideology. Both Mazdakism and Manichaeism were sub-branches of Zoroastrianism that is said to be the first monotheistic religion.

Sunni was the dominant form of Islam in most of Iran until rise of Safavid Empire. There were however some exceptions to this general domination of the Sunni creed which emerged in the form of the Zaydīs of Tabaristan, the Buwayhid, the rule of Sultan Muhammad Khudabandah (r. Shawwal 703-Shawwal 716/1304-1316CE), the Hashashin and the Sarbedaran. Nevertheless, apart from this domination there existed, firstly, throughout these nine centuries, Shia inclinations among many Sunnis of this land and, secondly, all three surviving branches of Shi'a Islam, Twelver, Ismaili, as well as Zaidi had prevalence in some parts of Iran. During this period, Shia in Iran were nourished from Kufah, Baghdad and later from Najaf and Hillah. [25] Shiism were dominant sect in Tabaristan, Qom, Kashan, Avaj and Sabzevar. In many other areas the population of Shia and Sunni was mixed. In recent centuries Ismailis have also largely been an Indo-Iranian community,[26].

Many scholars and scientists in Persia who lived before the Safavid era, such as Avicenna, Geber, Salman the Persian, Alhacen, Al-Farabi and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī, were Shi'a Muslims, as was most of Iran's elite, while other greatest Sunni Muslim scientists, scholars and personaliries were Persian or had Persian descent, including Abu Dawood, Hakim al-Nishaburi, Al-Tabarani, Ghazali, Imam Bukhari, Tirmidhi, Al-Nasa'i and Fakhr al-Din al-Razi, amongst many others. Abu Hanifa, the founder of the Sunni Hanafi school of Islamic jurisprudence is also widely accepted of Persian ancestry.

The first Shia regime, the Safavid dynasty in Iran, propagated the Twelver faith, made Twelver law the law of the land, and patronized Twelver scholarship. For this, Twelver ulama "crafted a new theory of government" which held that while "not truly legitimate", the Safavid monarchy would be "blessed as the most desirable form of government during the period of waiting" for the twelfth imam.[27]

Today, most Persians are Twelver Shia succeeded by Hanafi Sunni Muslims. There is also a sizeable number of Shafi`i Sunni Muslims in southern Iran and amongst Kurds. Small Ismaili Shia minorities also exist in scattered pockets. Some communities practice Shi'a Sufism. There are also smaller communities of Zoroastrians, Christians, Jews and Bahá'ís. Bahá'ís are the largest non-Muslim religious minority in Iran.[28]. There exists Persians who are atheist and agnostic. Also see religious minorities in Iran.

Culture

Persian culture can be defined through its films, as Persian cinema has attained a substantial amount of international and critical acclaim through such films as Children of Heaven and Taste of Cherry, which give both insights into the current state of Persian culture and profound depictions of the general human condition.

Arts

The artistic heritage of Persia is eclectic and includes major contributions from both east and west. Persian art borrowed heavily from the indigenous Elamite civilization and Mesopotamia and later from Hellenism (as can be seen with statues from the Greek period). In addition, due to Persia's somewhat central location, it has served as a fusion point between eastern and western arts and architecture as Greco-Roman influence was often fused with ideas and techniques from India and China. When talking of the creative Persian arts one has to include a geographic area that actually extends into Central Asia, the Caucasus, Asia Minor, and Iraq as well as modern Iran. This vast geographic region has been pivotal in the development of the Persian arts as a whole.

Statues

Persians' artistic expression can be seen as far back as the Achaemenid period as numerous statues depicting various important figures, usually of political significance as well as religious, such as the Immortals (elite troops of the emperor) are indicative of the influence of Mesopotamia and ancient Babylon. What is perhaps most representative of a more indigenous artistic expression are Persian miniatures. Although the influence of Chinese art is apparent, local Persian artists used the art form in various ways including portraits that could be seen from the Ottoman Empire to the courts of the Safavids and Mughals.

Music

The music of Persia goes back to the days of Barbad in the royal Sassanid courts, and even earlier. As it evolved, a distinct eastern Mediterranean style emerged as Persian folk music is often quite similar to the music of modern Iran's neighbors. In modern times, musical tradition has seen setbacks due to the religious government's policies in Iran, but has survived in the form of Iranian exiles and dissidents who have turned to Western rock music with a distinctive Iranian style as well as Persian rap.

Architecture

Architecture is one of the areas where Persians have made outstanding contributions. Ancient examples can be seen in the ruins at Persepolis, while in modern times monuments such as the Tomb of Omar Khayyam are displays of the varied tradition in Persia. Various cities in Iran are historical displays of a distinctive Persian style that can be seen in the Kharaghan twin towers of Qazvin province and the Shah Mosque found in Isfahan. Persian architecture streams over the borders of Iran and is clearly seen throughout Central Asia as with the Bibi Khanum Mosque in Samarkand as well as Samanids mausoleum in Bukhara and the Minaret of Jam in western Afghanistan. Islamic architecture was founded on the base established by the Persians. Persian techniques can also be clearly seen in the structures of the Taj Mahal at Agra and the Blue Mosque in Istanbul.

Rugs

Gottfried Semper called rugs "the original means of separating space". Rug weaving was thus developed by ancient civilizations as a basis of architecture. Persian rugs are said to be the most detailed hand-made works of art. Also known as the starus Rugs very important in the culture. Interworking of fibers to produce cloth was known in Iran as early as the 5th millennium BCE.[29] When the famous Greek commander Themistocles was asking for asylum from Persia , the “Persian carpet” was mentioned in his speech:

he [Artaxerxes I of Persia] commanded him to speak freely what he would concerning the affairs of Greece. Themistocles replied, that a man’s discourse was like to a rich Persian carpet, the beautiful figures and patterns of which can only be shown by spreading and extending it out; when it is contracted and folded up, they are obscured and lost; and, therefore, he desired time.

Gardens

The Persian gardens were designed to reflect paradise on earth; The English word paradise is thought to come from the Persian word Pardis, which refers to these gardens.

Although having existed since ancient times, the Persian garden gained greater prominence during the Islamic period as Arab rulers cultivated Persian techniques to create gardens of Persian design from Al-Andalus to Kashgar. Persian gardens are immortalized in the One Thousand and One Nights and the works of Omar Khayyam.

Women

Persian women have played an important role throughout history. Scheherazade, though fictional, is an important figure of female wit and intelligence, while the beauty of Mumtaz Mahal inspired the building of the Taj Mahal itself. While in ancient times, aristocratic females possessed numerous rights sometimes on par with men, generally Persian women did not attain greater parity until the 20th century. However, Táhirih, the poet, had a great influence on modern women's movements throughout the Middle East. The Táhirih Justice Center is named after her. Females were given such status in ancient Persia that they were the first to ever serve in a national military.

Persian women today serve an active role in society. Persian women today tend to take a more active role in social, religious and family affairs than their Arab counterparts. Persian women can be seen working in a variety of areas such as politics, law enforcement, transportation industries, etc. Universities still tend to be dominated by women in Iran and one may find a large number of female legislators in the Iranian Majlis (parliament), even by western standards. Former Vice President Masoumeh Ebtekar, noted for her eloquence in dealing with western media, set a new standard for aspiring Iranian female politicians while serving under President Khatami. Outstanding Iranian female academics, such as Laleh Bakhtiar have forever left a mark in the fields they contribute to.

Because of some restrictions, women in Iran suffer from inequality in many cases. Human rights in the Islamic Republic of Iran are not respected, hence many women prefer to migrate and continue their lives in other countries.

See also

|

|

|

References

- ↑ http://www.iranologie.com/history/history9.html

- ↑ Lands of Iran Encyclopedia Iranica (July 25, 2005) (retrieved 3 March 2008)

- ↑ Treaty of Turkmenchay, Treaty of Gulistan and Anglo-Persian War

- ↑ Abdolhossein Zarinkoob "Ruzgaran : tarikh-e Iran az aghaz ta soqut-e saltnat-e Pahlevi" pp. 37

- ↑ Bahman Firuzmandi "Mad, Hakhamaneshi, Ashkani, Sasani" pp. 155

- ↑ Liddell and Scott, Lexicon of the Greek Language, Oxford, 1882, p 1205

- ↑ http://www.livius.org/pan-paz/parthia/parthia02.html

- ↑ For example, Abu Rayhan Biruni, a native speaker of the Eastern Iranian language Chorasmian mentions in his Āthār al-bāqiyah ʻan al-qurūn al-xāliyah that: "the people of Khwarizm, they are a branch of the Persian tree." See: Abu Rahyan Biruni, "Athar al-Baqqiya 'an al-Qurun al-Xaliyyah" ("Vestiges of the past: chronology of ancient nations"), Tehran, Miras-e-Maktub, 2001. Original Arabic of the quote: "و أما أهل خوارزم، و إن کانوا غصنا ً من دوحة الفُرس"(pg 56)

- ↑ The language used in the ancient Marzbānnāma was, in the words of the 13th-century historian Sa'ad ad-Din Warawini, “ the language of Ṭabaristan and old, original Persian (fārsī-yi ḳadīm-i bāstān)”See: Kramers, J.H. "Marzban-nāma." Encyclopaedia of Islam. Edited by: P. Bearman , Th. Bianquis , C.E. Bosworth , E. van Donzel and W.P. Heinrichs. Brill, 2007. Brill Online. 18 November 2007 <http://www.brillonline.nl/subscriber/entry?entry=islam_SIM-4990>

- ↑ The language of Tabriz, being an Iranian language during the time of Qatran Tabrizi, was not the standard Khurasani Parsi-ye Dari. Qatran Tabrizi(11th century) has an interesting couplet mentioning this fact: Riyahi Khoi, Mohammad Amin. “Molehaazi darbaareyeh Zabaan-I Kohan Azerbaijan”(Some comments on the ancient language of Azerbaijan), ‘Itilia’at Siyasi Magazine, volume 181-182. Also available at: [1]

بلبل به سان مطرب بیدل فراز گل

گه پارسی نوازد، گاهی زند دری

Translation:

The nightingale is on top of the flower like a minstrel who has lost her heart It bemoans sometimes in Parsi (Persian) and sometimes in Dari (Khurasani Persian) - ↑ Lady (Mary) Shiel in her observation of Persia during the Qajar describes the Persian tribes and Koords/Laks identified themselves and were identified commonly as Old Persians. See: Shiel, Lady (Mary). Glimpses of Life and Manners in Persia. London: John Murray, 1856. See:[2], excerpt:

The PERSIAN TRIBES. The tribes are divided into three races-Toorks, Leks, first are the invaders from Toorkistan, who, from time 'immemorial, have established themselves in Persia, and who still preserve their language. The Leks form the clans of genuine Persian blood, such as the Loors, BekhtiaTees, &c. To them might be added the Koords, as members of the Persian family; but their numbers in the dominions of the Shah are comparatively few, the greater part of that widely-spread people being attached to Turkey. Collectively the Koords are so numerous that they might be regarded as a nation divided into distinct tribes. Who are the Leks, and who are the Koords? This in- quiry I cannot solve. I never met any one in Persia, either eel or moolla, who could give the least elucidation of this question. All they could say was, that both these races were Foors e kadeem,-old Persians. They both speak dialects the greater part of which is Persian, bearing a strong resemblance to the colloquial language of the present day, divested of its large Arabic mixture. These dialects are not perfectly alike, though it is said that Leks and Koords are able to comprehend each other. One would be disposed to consider them as belonging to the same stock,. did they not both disavow the connection. A Lek will- admit that a Koord, like himself, is an 11 old Persian," but he denies that the families are identical, and a Koord views the question in the same light. - ↑ (Al Mas'udi, Kitab al-Tanbih wa-l-Ishraf, De Goeje, M.J. (ed.), Leiden, Brill, 1894, pp. 77-8). Original Arabic from www.alwaraq.net: فالفرس أمة حد بلادها الجبال من الماهات وغيرها وآذربيجان إلى ما يلي بلاد أرمينية وأران والبيلقان إلى دربند وهو الباب والأبواب والري وطبرستن والمسقط والشابران وجرجان وابرشهر، وهي نيسابور، وهراة ومرو وغير ذلك من بلاد خراسان وسجستان وكرمان وفارس والأهواز، وما اتصل بذلك من أرض الأعاجم في هذا الوقت وكل هذه البلاد كانت مملكة واحدة ملكها ملك واحد ولسانها واحد، إلا أنهم كانوا يتباينون في شيء يسير من اللغات وذلك أن اللغة إنما تكون واحدة بأن تكون حروفها التي تكتب واحدة وتأليف حروفها تأليف واحد، وإن اختلفت بعد ذلك في سائر الأشياء الأخر كالفهلوية والدرية والآذرية وغيرها من لغات الفرس.

- ↑ Ghani, Cyrus. Iran and the Rise of Reza Shah: From Qajar Collapse to Pahlavi Power, 2001, p. 310, I.B.Tauris. ISBN 1860646298

- ↑ Persian entry in the Merriam-Webster online dictionary [3]

- ↑ The American Heritage Dictionary of the English Language: Fourth Edition (2000). [4]

- ↑ Bausani, Alessandro. The Persians, from the earliest days to the twentieth century. 1971, Elek. ISBN 978-0236177608

- ↑ Iran :: Ethnic groups - Britannica Online Encyclopedia

- ↑ The Medes and the Persians, c.1500-559 from The Encyclopedia of World History Sixth Edition, Peter N. Stearns (general editor), © 2001 The Houghton Mifflin Company, at Bartleby.com.

- ↑ Bahman Firuzmandi "Mad, Hakhamanishi, Ashkani, Sasani" pp. 20

- ↑ Iran. The Columbia Encyclopedia, Sixth Edition. 2001-05

- ↑ Bahman Firuzmandi "Mad, Hakhamanishi, Ashkani, Sasani" pp. 12-19

- ↑ Persia - Britannica Concise Encyclopedia

- ↑ The Splendor of Persia: The Land and the People - by Robert Payne

- ↑ BBC News - Afghan poll's ethnic battleground

- ↑ Four Centuries of Influence of Iraqi Shiism on Pre-Safavid Iran

- ↑ Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.76

- ↑ Nasr, Vali, The Shia Revival, Norton, (2006), p.74-75

- ↑ Federation Internationale des Ligues des Droits de L'Homme (2003-08). "Discrimination against religious minorities in IRAN" (PDF). fidh.org. Retrieved on 2006-10-04.

- ↑ Rubinson, Karen S "carpets :vi.pre-Islamic carpets (pages 858 – 861)". Encyclopedia Iranica. Retrieved on 2008-05-11.

- ↑ Themistocles. Plutarch. 1909-14. Plutarch’s Lives. The Harvard Classics