Perpetual motion

The term perpetual motion, taken literally, refers to movement that goes on forever. However, the term more generally refers to any closed system that produces more energy than it consumes. Such a device or system would be in violation of the law of conservation of energy, which states that energy can never be created or destroyed. The most conventional type of perpetual motion machine is a mechanical system which (supposedly) sustains motion despite losing energy to friction and air resistance, or while avoiding losing energy to friction and air resistance. According to the law of conservation of energy, such a device cannot exist.

Contents |

Basic principles

Perpetual motion violates either the first law of thermodynamics, the second law of thermodynamics, or both. The first law of thermodynamics is essentially a statement of conservation of energy. The second law can be phrased in several different ways, the most intuitive of which is that heat flows spontaneously from hotter to colder places; the most well known statement is that entropy tends to increase, or at the least stay the same; another statement is that no heat engine (an engine which produces work while moving heat between two places) can be more efficient than a Carnot heat engine. As a special case of this, any machine operating in a closed cycle cannot only transform thermal energy to work in a region of constant temperature.

Machines which are claimed not to violate either of the two laws of thermodynamics but rather are claimed to generate energy from unconventional sources are sometimes referred to as perpetual motion machines, although they are generally reported as not meeting the standard criteria for the name. By way of example, it is quite possible to design a clock or other low-power machine to run on the differences in barometric pressure or temperature between night and day.[2] Such a machine has a source of energy, albeit one from which it is quite impractical to produce power in quantity.

Classification

It is customary to classify perpetual motion machines according to which law of thermodynamics it attempts to violate:

- A perpetual motion machine of the first kind produces energy from nothing, giving the user unlimited 'free' energy. It thus violates the law of conservation of energy.

- A perpetual motion machine of the second kind is a machine which spontaneously converts thermal energy into mechanical work. This need not violate the law of conservation of energy, since the thermal energy may be equivalent to the work done; however it does violate the more subtle second law of thermodynamics (see also entropy). Note that such a machine is different from real heat engines (such as car engines), which always involve a transfer of heat from a hotter reservoir to a colder one, the latter being warmed up in the process. The signature of a perpetual motion machine of the second kind is that there is only one single heat reservoir involved, which is being spontaneously cooled without involving a transfer of heat to a cooler reservoir. This conversion of heat into useful work, without any side effect, is impossible by the second law of thermodynamics. What may prove more useful is to explain the existence of hot reservoirs to begin with. A hot reservoir inside an internal combustion engine is created by a spark igniting fumes which contain stores of chemical energy. The temperature of the fumes increases above that of the surroundings. This is not a perpetual motion machine since the ability to raise the temperature above that of the surroundings depends on finite chemical reactions always less than the total heat energy and mass-energy contained within the system. Since there are far more states in which heat distribution is closer to thermodynamic equilibrium than states in which heat is concentrated in small regions, heat will tend to smooth out over time to lower power densities of increasingly unusable forms.

- A more obscure category is a perpetual motion machine of the third kind, usually (but not always)[3] defined as one that completely eliminates friction and other dissipative forces, to maintain motion forever. Third in this case refers solely to place in the above classification scheme, not the third law of thermodynamics. Although it is impossible to make such a machine,[4][5] as dissipation can never be 100% eliminated in a mechanical system, it is nevertheless possible to get very close to this ideal (for example, flywheels that can spin for hours). Moreover, in certain quantum-mechanical systems (such as superfluidity and superconductivity), dissipation-free "motion" is possible. In any case, even if such a machine could be built, it would not serve as an endless source of energy, since any energy-extracting mechanism would also serve as a dissipative force.

Use of the term "impossible" and perpetual motion

Like all scientific theories, the laws of physics are incomplete. "A world that was simple enough to be fully known would be too simple to contain conscious observers that might know it."[6] Outside of pure mathematics, stating that things are absolutely impossible is more a hallmark of pseudoscience than of true science. Nevertheless, the term is properly used to reflect those things that cannot be true without a significant rewrite of nearly all known scientific laws.[7]

The conservation laws are particularly robust. Noether's theorem states that any conservation law can be derived from a corresponding continuous symmetry.[8] In other words, so long as the laws of physics (not simply the current understanding of them, but the actual laws, which may still be undiscovered) and the various physical constants remain invariant over time — so long as the laws of the universe are fixed — then the conservation laws must be true, in the sense that they follow from the presupposition using mathematical logic. To put it the other way around: if perpetual motion or "overunity" machines were possible, then most of what we believe to be true about physics, mathematics, or both would have to be false. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that mathematics is believed to be absolute, since its veracity is not dependent on anything that happens in the real world.

In this case it is easy to check whether or not the theory is correct. Using telescopes we can examine the universe in the distant past; the fact that stars even exist and are, to the limits of our measurements, identical to stars today, is a direct visual demonstration that physics was similar in the past. Combining different measurements such as spectroscopy, direct measurement of the speed of light in the past and similar measurements demonstrates conclusively that physics has remained substantially the same, if not identical, for all of observable history spanning billions of years.[9]

The principles of thermodynamics are so well established, both theoretically and experimentally, that proposals for perpetual motion machines are universally met with disbelief on the part of physicists. Any proposed perpetual motion design offers a potentially instructive challenge to physicists: one is almost completely certain that it can't work, so one must explain how it fails to work. The difficulty (and the value) of such an exercise depends on the subtlety of the proposal; the best ones tend to arise from physicists' own thought experiments and often shed light into unique aspects of physics.

The law that entropy always increases, holds, I think, the supreme position among the laws of Nature. If someone points out to you that your pet theory of the universe is in disagreement with Maxwell's equations — then so much the worse for Maxwell's equations. If it is found to be contradicted by observation — well, these experimentalists do bungle things sometimes. But if your theory is found to be against the second law of thermodynamics I can give you no hope; there is nothing for it but to collapse in deepest humiliation. — Sir Arthur Stanley Eddington, The Nature of the Physical World (1927)

Thought experiments

Serious work in theoretical physics often involves thought experiments that test the boundaries of understanding of physical laws. Some such thought experiments involve apparent perpetual motion machines, and insight may be had from understanding why they either don't work or don't violate the laws of physics.

- Maxwell's demon: A thought experiment which led to physicists' considering the interaction between entropy and information.

- Feynman's "Brownian ratchet": A "perpetual motion" machine which extracts work from thermal fluctuations and appears to run forever but really only runs as long as the environment is warmer than the ratchet.

- Self-perpetuating cosmic inflation: Andrei Linde has proposed that during the theoretical period of cosmic inflation in the early universe, quantum fluctuations in energy could be magnified by the very inflationary process, preventing the global cooling trend from ever being fully consummated. This would violate both the first and second laws of thermodynamics; indeed, it may constitute the origin of a low-entropy past that gets the second law going in the first place. However, a machine to harness this principle would have several serious flaws. It would need to use unimaginable amounts of energy (on at least a Planck scale); it might have cataclysmic consequences to the area around it for an unknown distance (there is not a prior natural limit to the scale of the damage); and at least the majority and possibly all the energy it generated would be in a newly-created universe which might be inaccessibly far away along a wormhole.

Techniques

| “ | One day man will connect his apparatus to the very wheelwork of the universe [...] and the very forces that motivate the planets in their orbits and cause them to rotate will rotate his own machinery. | ” |

Some common ideas recur repeatedly in perpetual motion machine designs. Many of the ones that continue to appear today were already outlined by John Wilkins, Bishop of Chester and an early official of the Royal Society. In 1670 Wilkins outlined three potential sources of power for a perpetual motion machine, "Chymical Extractions", "Magnetical Virtues" and "the Natural Affection of Gravity".[1]

The seemingly mysterious ability of magnets to influence motion at a distance without any apparent energy source has long appealed to inventors. One of the earliest examples of a system using magnets was proposed by Wilkins and has been widely copied since; it consists of a ramp with a magnet at the top, which pulled a metal ball up the ramp. Near the magnet was a small hole that was supposed to allow the ball to drop under the ramp and return to the bottom, where a flap allowed it to return to the top again. The device simply could not work; any magnet strong enough to pull the ball up the ramp would necessarily be too powerful to allow it to drop through the hole. Faced with this problem, more modern versions typically use a series of ramps and magnets, positioned so the ball is to be handed off from one magnet to another as it moves. The problem remains the same.

In a more general sense, magnets can do no net work, although this was not understood until much later. A magnet can accelerate an object, like the metal ball of Wilkins' device, but this motion will always come to stop when the object reaches the magnet, releasing that work in some other form - typically its mechanical energy being turned into heat. In order for this motion to continue, the magnet would have to be moved, which would require energy.

Gravity also acts at a distance, without an apparent energy source. But to get energy out of a gravitational field (for instance, by dropping a heavy object, producing kinetic energy as it falls) you have to put energy in (for instance, by lifting the object up), and some energy is always dissipated in the process. A typical application of gravity in a perpetual motion machine is Bhaskara's wheel in the 12th century, whose key idea is itself a recurring theme, often called the overbalanced wheel: Moving weights are attached to a wheel in such a way that they fall to a position further from the wheel's center for one half of the wheel's rotation, and closer to the center for the other half. Since weights further from the center apply a greater torque, the result is (or would be, if such a device worked) that the wheel rotates forever. The moving weights may be hammers on pivoted arms, or rolling balls, or mercury in tubes; the principle is the same.

Yet another theoretical machine involves a frictionless environment for motion. This involves the use of diamagnetic or electromagnet levitation to float an object. This is done in a vacuum to eliminate air friction and friction from an axle. The levitated object is then free to rotate around its center of gravity without interference. However, this machine has no practical purpose because the rotated object cannot do any work as work requires the levitated object to cause motion in other objects, bringing friction into the problem.

To extract work from heat, thus producing a perpetual motion machine of the second kind, the most common approach (dating back at least to Maxwell's demon) is unidirectionality. Only molecules moving fast enough and in the right direction are allowed through the demon's trap door. In a Brownian ratchet, forces tending to turn the ratchet one way are able to do so while forces in the other direction aren't. A diode in a heat bath allows through currents in one direction and not the other. These schemes typically fail in two ways: either maintaining the unidirectionality costs energy (Maxwell's demon needs light to look at all those particles and see what they're doing), or the unidirectionality is an illusion and occasional big violations make up for the frequent small non-violations (the Brownian ratchet will be subject to internal Brownian forces and therefore will sometimes turn the wrong way).

Invention history

The earliest references to perpetual motion machines date back to 1150, by an Indian mathematician-astronomer, Bhāskara II. He described a wheel that he claimed would run forever.[10]

Villard de Honnecourt in 1235 described, in a thirty-three page manuscript, a perpetual motion machine of the second kind. His idea was based on changing torque of a series of weights around the rim of a wheel. The weights were positioned so that they would fall

His device spawned a variety of imitators that have continued

Robert Boyle's self-flowing flask appears to fill itself through siphon action. This is not possible in reality; a siphon requires its "output" to be lower than the "input".

In 1775 Royal Academy of Sciences in Paris issued the statement that Academy "will no longer accept or deal with proposals concerning perpetual motion". Johann Bessler (also known as Orffyreus) created a series of claimed perpetual motion machines in the 18th Century. In the 19th century, the invention of perpetual motion machines became an obsession for many scientists. Many machines were designed based on electricity, but none of them lived up to their promises. Another early prospector in this field was John Gamgee. Gamgee developed the Zeromotor, a perpetual motion machine of the second kind.

Devising these machines is a favourite pastime of many eccentrics, who often come up with elaborate machines in the style of Rube Goldberg or Heath Robinson. These designs may appear to work on paper at first glance. Usually, though, various flaws or obfuscated external power sources have been incorporated into the machine. Such activity has made them useless in the practice of "invention".

Patents

Devising such inoperable machines has become common enough that the United States Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) has made an official policy of refusing to grant patents for perpetual motion machines without a working model. The USPTO Manual of Patent Examining Practice states:

- With the exception of cases involving perpetual motion, a model is not ordinarily required by the Office to demonstrate the operability of a device. If operability of a device is questioned, the applicant must establish it to the satisfaction of the examiner, but he or she may choose his or her own way of so doing.[11]

And, further, that:

- A rejection [of a patent application] on the ground of lack of utility includes the more specific grounds of inoperativeness, involving perpetual motion. A rejection under 35 U.S.C. 101 for lack of utility should not be based on grounds that the invention is frivolous, fraudulent or against public policy.[12]

The USPTO has granted a few patents for motors that are claimed to run without net energy input. Some of these are:

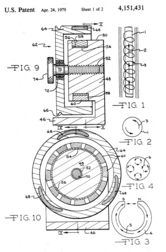

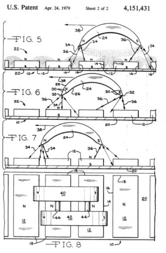

| Howard R. Johnson, U.S. Patent 4,151,431 |

|---|

|

- Johnson, Howard R., U.S. Patent 4,151,431 "Permanent magnet motor", April 24, 1979

- Baker, Daniel, U.S. Patent 4,074,153 "Magnetic propulsion device", February 14, 1978

- Hartman; Emil T., U.S. Patent 4,215,330 "Permanent magnet propulsion system", December 20, 1977 (this device is related to the Simple Magnetic Overunity Toy (SMOT)),

- Flynn; Charles J., U.S. Patent 6,246,561 "Methods for controlling the path of magnetic flux from a permanent magnet and devices incorporating the same", July 31, 1998

- Patrick, et al., U.S. Patent 6,362,718 "Motionless electromagnetic generator" , March 26, 2002

- Green, Willie A., U.S. Patent 6,526,925 "Piston Driven Rotary Engine", March 4, 2003 "Fluid driven device utilizing a leveraged system with minimal displacement"

- Goldenblum, Halm, U.S. Patent 6,962,052 "Energy generation mechanism, device and system", November 8, 2005 "A chamber with a partition which lets gas molecules flow one way and not the other. The pressure which builds up on one side of the partition is used to drive a generator."

- Flynn, Joe, U.S. Patent 6,246,561 "Methods for controlling the path of magnetic flux from a permanent magnet and devices incorporating the same", June 12, 2001

- Gates; Glenn A., U.S. Patent 6,523,646 "Spring driven apparatus", February 23, 2003 "Energy is stored in the springs and power is generated by way of the various forces which cause the springs to wind and unwind."

- McQueen; Jesse, U.S. Patent 7,095,126 "Internal energy generating power source", August 22, 2006 "An external power source such as a battery is used to initially supply power to start an alternator and generator. Once the system has started it is not necessary for the battery to supply power to the system. The battery can then be disconnected. The alternator and electric motor work in combination to generator electrical power." Examiners: Schuberg, Darren ; Mohandesi, Iraj A.

- Haisch, et al. U.S. Patent 7,379,286 "Quantum vacuum energy extraction", May 27, 2008 "[...] converting energy from the electromagnetic quantum vacuum available at any point in the universe to usable energy in the form of heat, electricity, mechanical energy or other forms of power. [...] When atoms enter into suitable micro Casimir cavities a decrease in the orbital energies of electrons in atoms will thus occur. Such energy will be captured in the claimed devices. Upon emergence form such micro Casimir cavities the atoms will be re-energized by the ambient electromagnetic quantum vacuum. [...] process is also consistent with the conservation of energy in that all usable energy does come at the expense of the energy content of the electromagnetic quantum vacuum."

In 1979, Joseph Newman filed a US Patent application for his "energy machine" which unambiguously claimed over-unity operation, where power output exceeded power input; the source of energy was claimed to be the atoms of the machine's copper conductor.[13] The Patent Office rejected the application after the National Bureau of Standards measured the electrical input to be greater than the electrical output. Newman challenged the decision in court and lost.[14]

Other patent offices around the world have similar practices, such as the United Kingdom Patent Office. Section 4.05 of the UKPO Manual of Patent Practice states:

- Processes or articles alleged to operate in a manner which is clearly contrary to well-established physical laws, such as perpetual motion machines, are regarded as not having industrial application.[15]

Examples of decisions by the UK Patent Office to refuse patent applications for perpetual motion machines include: [16]

- Decision BL O/044/06, John Frederick Willmott's application no. 0502841[17]

- Decision BL O/150/06, Ezra Shimshi's application no. 0417271[18]

The European Patent Classification (ECLA) has classes including patent applications on perpetual motion systems: ECLA classes "F03B17/04: Alleged perpetua mobilia ..." and "F03B17/00B: [... machines or engines] (with closed loop circulation or similar : ...Installations wherein the liquid circulates in a closed loop; Alleged perpetua mobilia of this or similar kind ...". [19]

Recent examples

As the term "perpetual energy" increasingly became associated with fraud in the late 19th century, inventors have generally avoided the term. Today devices described as perpetual motion devices claim to operate by extracting "zero point energy" or some other source of external energy.

- Motionless Electromagnetic Generator, a device that supposedly taps vacuum energy.

- Perepiteia, a device that claims to utilize back EMF.

- Steorn Ltd., a company that claims to have built a motor using only permanent magnets.

- Stanley Meyer's water fuel cell A device that purportedly powered a car by converting water into hydrogen and harnessing the energy of hydrogen combustion (which, in turn, emits water vapor that can be refueled to the car)

Apparent perpetual motion machines

Even though they fully respect the laws of thermodynamics, there are a few conceptual or real devices that appear to be in "perpetual motion." Closer analysis reveals them to actually "consume" some sort of natural resource or latent energy like the phase changes of water or other fluids or small natural temperature gradients. In general, extracting large amounts of work using these devices is difficult to impossible.

Some examples of such devices include:

- The drinking bird toy functions using small ambient temperature gradients and evaporation.

- A capillarity based water pump functions using small ambient temperature gradients and vapour pressure differences.

- A Crookes radiometer consists of a partial vacuum glass container with a lightweight propeller moved by (light-induced) temperature gradients.

- Any device picking up minimal amounts of energy from the natural electromagnetic radiation around it, such as a solar powered motor.

- The Atmos clock uses changes in the vapor pressure of ethyl chloride with temperature to wind the clock spring.

Ubiquitous energy from atomic and chemical bonds

- See also: Activation energy, Entropy, and Thermodynamics

All working energy devices require either a heat reservoir (such as solar radiation) or a process of utilizing dense stores of energy (such as nuclear energy or chemical energy). Heat pumps are capable of transporting this waste heat in excess of the heat used to run them (cf. Coefficient of performance>1), but are not perpetual motion machines because the transferred heat is part of the input.

Conventional sources of energy such as petroleum and natural gas or radioactive materials such as uranium rely on a small fraction of the inherent and ubiquitous energy of atoms and molecules, although the energy of atoms and molecules are not characterized by an internal temperature. Electrical power plants can only be profitable by extracting the nuclear and chemical energies in excess of the energy needed to:

- locate and mine the construction materials, process them into usable form (concrete, steel), and build the plant

- locate, mine/extract, transport, purify, concentrate, and react the fuel materials

- operate the plant in a safe and stable manner

- repurify uranium waste back into usable fuel

- decommission and dismantle the retired power plants

Scientists are currently spending many research hours in attempt of getting more power out of nuclear fusion than what it takes to run the power plant. If solved, nuclear fusion would supply the world with an abundant source of electricity. The entire energy industry relies on a system where thermal output exceeds the thermal input. When determining the present thermal output that exceeds present thermal input, one only considers the time during which the energy of the fuel is consumed, and not the time during which the energy was stored in that fuel.

Gallery

This is a gallery of some of the perpetual motion machine plans.

Free energy suppression

Self-taught inventors exploring the topics of perpetual motion are often highly secretive of their work and unwilling to openly discuss what they are doing, instead offering only limited-access demonstrations without explanation or documentation. They claim to do this for a number of reasons:[20]

- They are afraid their potentially highly valuable idea will be stolen.

- They are afraid of physical violence from disrupting the business of established energy providers.

- They are afraid of the military declaring their work top secret and confiscating the work for military application or weaponization.

- They are afraid government agencies will shut them down to preserve taxes.

See also

- John Ernst Worrell Keely

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Stanley Angrist, "Perpetual Motion Machines", Scientific American", January 1968, Vol. 218, No. 1, pp. 115-122

- ↑ Cox's timepiece

- ↑ An alternate definition is given, for example, by (Schadewald 2008:55-56), who defines a "perpetual motion machine of the third kind" as a machine that violates the third law of thermodynamics.

- ↑ Thermodynamics for Engineers, p154

- ↑ Mechanical Sciences: Engineering Thermodynamics and Fluid Mechanics, p51

- ↑ Barrow, John D.. Impossibility:The limits of science and the science of limits. p. 3.

- ↑ Barrow, John D.. Impossibility:The limits of science and the science of limits.

- ↑ Goldstein, Herbert; Charles Poole and John Safko (2002). Classical Mechanics 3rd edition. San Francisco, CA: Addison Wesley. pp. 589-598. ISBN 0-201-65702-3.

- ↑ "CE410: Are constants constant?", talkorigins

- ↑ Lynn Townsend White, Jr. (April 1960). "Tibet, India, and Malaya as Sources of Western Medieval Technology", The American Historical Review 65 (3), p. 522-526.

- ↑ 608.03 Models, Exhibits, Specimens [R-3 – 600 Parts, Form, and Content of Application]

- ↑ 706.03(a) Rejections Under 35 U.S.C. 101 [R-3 – 700 Examination of Applications II. UTILITY]

- ↑ "A Patent Pursuit: Joe Newman's 'Energy Machine', Science News, June 1, 1985

- ↑ "NBS Report Short Circuits Energy Machine", Science News, July 5, 1986

- ↑ http://www.patent.gov.uk/practice-sec-004.pdf

- ↑ See also, for more examples of refused patent applications at the United Kingdom Patent Office (UK-IPO), UK-IPO gets tougher on perpetual motion, IPKat, 12 June 2008. Consulted on June 12, 2008.

- ↑ Patents Ex parte decision (O/044/06)

- ↑ http://www.patent.gov.uk/patent/p-decisionmaking/p-challenge/p-challenge-decision-results/o15006.pdf

- ↑ ECLA classes F03B17/04 and F03B17/00B. Consulted on June 12, 2008.

- ↑ A YouTube video that covers all the conspiracy bases: Free Energy - Pentagon Conspiracy to Cover up http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=uGRsQZx6zWA

External links

- Veljko Milković and Nebojša Simin (2001). Perpetuum mobile. Novi Sad (Serbia), Vrelo. http://www.veljkomilkovic.com/KnjigeEng.html#perpetum.

- Schadewald, Robert J. (2008), Worlds of Their Own - A Brief History of Misguided Ideas: Creationism, Flat-Earthism, Energy Scams, and the Velikovsky Affair, Xlibris, ISBN 978-1-4636-0435-1

- Perpetuum Mobile Video.

- [1] Perpetual park video.

- Perpetuum Mobile Site.

Historic

- The Museum of Unworkable Devices

- Donald Simanek's History of Perpetual Motion Machines

- Richard Clegg, "Perpetual Motion Page", richardclegg.org.

- A selection of Bhaskara-like devices