Peptic ulcer

| Peptic ulcer Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

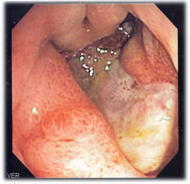

| Deep gastric ulcer | |

| ICD-10 | K25.-K27. |

| ICD-9 | 531-534 |

| DiseasesDB | 9819 |

| eMedicine | med/1776 ped/2341 |

| MeSH | D010437 |

A peptic ulcer, also known as ulcus pepticum, PUD or peptic ulcer disease[1], is an ulcer (defined as mucosal erosions equal to or greater than 0.5 cm) of an area of the gastrointestinal tract that is usually acidic and thus extremely painful. As much as 80% of ulcers are associated with Helicobacter pylori, a spiral-shaped bacterium that lives in the acidic environment of the stomach, however only 20% of those cases go to a doctor. Ulcers can also be caused or worsened by drugs such as aspirin and other NSAIDs. Contrary to general belief, more peptic ulcers arise in the duodenum (first part of the small intestine, just after the stomach) than in the stomach. About 4% of stomach ulcers are caused by a malignant tumor, so multiple biopsies are needed to make sure. Duodenal ulcers are generally benign.

Contents |

Classification

A peptic ulcer may arise at various locations:

- Stomach (called gastric ulcer)

- Duodenum (called duodenal ulcer)

- Esophagus (called esophageal ulcer)

- Meckel's Diverticulum (called Meckel's Diverticulum ulcer)

Types of peptic ulcers:

- Type I: Ulcer along the lesser curve of stomach

- Type II: Two ulcers present - one gastric, one duodenal

- Type III: Prepyloric ulcer

- Type IV: Proximal gastresophageal ulcer

- Type V: Anywhere along gastric body, NSAID induced

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms of a peptic ulcer can be

- abdominal pain, classically epigastric with severity relating to mealtimes, after around 3 hours of taking a meal (duodenal ulcers are classically relieved by food, while gastric ulcers are exacerbated by it);

- bloating and abdominal fullness;

- waterbrash (rush of saliva after an episode of regurgitation to dilute the acid in esophagus);

- nausea, and lots of vomiting;

- loss of appetite and weight loss;

- hematemesis (vomiting of blood); this can occur due to bleeding directly from a gastric ulcer, or from damage to the esophagus from severe/continuing vomiting.

- melena (tarry, foul-smelling feces due to oxidized iron from hemoglobin);

- rarely, an ulcer can lead to a gastric or duodenal perforation. This is extremely painful and requires immediate surgery.

A history of heartburn, gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and use of certain forms of medication can raise the suspicion for peptic ulcer. Medicines associated with peptic ulcer include NSAID (non-steroid anti-inflammatory drugs) that inhibit cyclooxygenase, and most glucocorticoids (e.g. dexamethasone and prednisolone).

In patients over 45 with more than two weeks of the above symptoms, the odds for peptic ulceration are high enough to warrant rapid investigation by EGD (see below).

The timing of the symptoms in relation to the meal may differentiate between gastric and duodenal ulcers: A gastric ulcer would give epigastric pain during the meal, as gastric acid is secreted, or after the meal, as the alkaline duodenal contents reflux into the stomach. Symptoms of duodenal ulcers would manifest mostly before the meal—when acid (production stimulated by hunger) is passed into the duodenum. However, this is not a reliable sign in clinical practice.

Complications

- Gastrointestinal bleeding is the most common complication. Sudden large bleeding can be life threatening[2]. It occurs when the ulcer erodes one of the blood vessels.

- Perforation (a hole in the wall) often leads to catastrophic consequences. Erosion of the gastro-intestinal wall by the ulcer leads to spillage of stomach or intestinal content into abdominal cavity. Perforation at the anterior surface of stomach leads to acute peritonitis, initially chemical and later bacterial peritonitis. Often first sign is sudden intense abdominal pain. Posterior wall perforation leads to pancreatitis; pain in this situation often radiates to back.

- Penetration is when the ulcer continues into adjacent organs such as liver and pancreas[3].

- Scarring and swelling due to ulcers causes narrowing in the duodenum and gastric outlet obstruction. Patient often presents with severe vomiting.

- Pyloric stenosis

Pathophysiology

Tobacco smoking, not eating properly, blood group, spices and other factors that were suspected to cause ulcers until late in the 20th century, are actually of relatively minor importance in the development of peptic ulcers.[4]

A major causative factor (60% of gastric and up to 90% of duodenal ulcers) is chronic inflammation due to Helicobacter pylori that colonizes (i.e. settles there after entering the body) the antral mucosa. The immune system is unable to clear the infection, despite the appearance of antibodies. Thus, the bacterium can cause a chronic active gastritis (type B gastritis), resulting in a defect in the regulation of gastrin production by that part of the stomach, and gastrin secretion can either be decreased (most cases) resulting in hypo- or achlorhydria or increased. Gastrin stimulates the production of gastric acid by parietal cells and, in H. pylori colonization responses that increase gastrin, the increase in acid can contribute to the erosion of the mucosa and therefore ulcer formation. Studies [5] have shown eating cabbage or cabbage juice can increase the mucosa lining in the stomach.

Another major cause is the use of NSAIDs (see above). The gastric mucosa protects itself from gastric acid with a layer of mucus, the secretion of which is stimulated by certain prostaglandins. NSAIDs block the function of cyclooxygenase 1 (cox-1), which is essential for the production of these prostaglandins. Newer NSAIDs (celecoxib, rofecoxib) only inhibit cox-2, which is less essential in the gastric mucosa, and roughly halve the risk of NSAID-related gastric ulceration. As the prevalence of H. pylori-caused ulceration declines in the Western world due to increased medical treatment, a greater proportion of ulcers will be due to increasing NSAID use among individuals with pain syndromes as well as the growth of aging populations that develop arthritis.

Glucocorticoids lead to atrophy of all epithelial tissues. Their role in ulcerogenesis is relatively small.

There is debate as to whether Stress in the psychological sense can influence the development of peptic ulcers. Burns and head trauma, however, can lead to "stress ulcers", and it is reported in many patients who are on mechanical ventilation.

Smoking leads to atherosclerosis and vascular spasms, causing vascular insufficiency and promoting the development of ulcers through ischemia.

A family history is often present in duodenal ulcers, especially when blood group O is also present. Inheritance appears to be unimportant in gastric ulcers.

Gastrinomas (Zollinger Ellison syndrome), rare gastrin-secreting tumors, cause multiple and difficult to heal ulcers.

Stress and ulcers

Despite the finding that a bacterial infection is the cause of ulcers in 80% of cases, bacterial infection does not appear to explain all ulcers and researchers continue to look at stress as a possible cause, or at least a complication in the development of ulcers.

An expert panel convened by the Academy of Behavioral Medicine research concluded that ulcers are not purely an infectious disease and that psychological factors do play a significant role.[1] Researchers are examining how stress might promote H. pylori infection. For example, Helicobacter pylori thrives in an acidic environment, and stress has been demonstrated to cause the production of excess stomach acid.

A study of peptic ulcer patients in a Thai hospital showed that chronic stress was strongly associated with an increased risk of peptic ulcer, and a combination of chronic stress and irregular mealtimes was a significant risk factor.[6]

A study on mice showed that both long-term water-immersion-restraint stress and H. pylori infection were independently associated with the development of peptic ulcers.[7]

Differential diagnosis of epigastric pain

- Peptic ulcer

- Gastritis

- Gastric carcinoma

- GERD

- Pancreatitis

- Hepatic congestion

- Cholecystitis

- Biliary colic

- Inferior myocardial infarction

- Referred pain (pleurisy, pericarditis, MI)

Diagnosis

An esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD), a form of endoscopy, also known as a gastroscopy, is carried out on patients in whom a peptic ulcer is suspected. By direct visual identification, the location and severity of an ulcer can be described. Moreover, if no ulcer is present, EGD can often provide an alternative diagnosis.

The diagnosis of Helicobacter pylori can be made by:

- Urea breath test (noninvasive and does not require EGD);

- Direct culture from an EGD biopsy specimen; this is difficult to do, and can be expensive. Most labs are not set up to perform H. pylori cultures;

- Direct detection of urease activity in a biopsy specimen by rapid urease test;

- Measurement of antibody levels in blood (does not require EGD). It is still somewhat controversial whether a positive antibody without EGD is enough to warrant eradication therapy;

- Stool antigen test;

- Histological examination and staining of an EGD biopsy.

The possibility of other causes of ulcers, notably malignancy (gastric cancer) needs to be kept in mind. This is especially true in ulcers of the greater (large) curvature of the stomach; most are also a consequence of chronic H. pylori infection.

If a peptic ulcer perforates, air will leak from the inside of the gastrointestinal tract (which always contains some air) to the peritoneal cavity (which normally never contains air). This leads to "free gas" within the peritoneal cavity. If the patient stands erect, as when having a chest X-ray, the gas will float to a position underneath the diaphragm. Therefore, gas in the peritoneal cavity, shown on an erect chest X-ray or supine lateral abdominal X-ray, is an omen of perforated peptic ulcer disease.

Macroscopical appearance

Gastric ulcers are most often localized on the lesser curvature of the stomach. The ulcer is a round to oval parietal defect ("hole"), 2 to 4 cm diameter, with a smooth base and perpendicular borders. These borders are not elevated or irregular in the acute form of peptic ulcer, regular but with elevated borders and inflammatory surrounding in the chronic form. In the ulcerative form of gastric cancer the borders are irregular. Surrounding mucosa may present radial folds, as a consequence of the parietal scarring.

Microscopical appearance

A gastric peptic ulcer is a mucosal defect which penetrates the muscularis mucosae and muscularis propria, produced by acid-pepsin aggression. Ulcer margins are perpendicular and present chronic gastritis. During the active phase, the base of the ulcer shows 4 zones: inflammatory exudate, fibrinoid necrosis, granulation tissue and fibrous tissue. The fibrous base of the ulcer may contain vessels with thickened wall or with thrombosis.[8]

Treatment

Younger patients with ulcer-like symptoms are often treated with antacids or H2 antagonists before EGD is undertaken. Bismuth compounds may actually reduce or even clear organisms.

Patients who are taking nonsteroidal anti-inflammatories (NSAIDs) may also be prescribed a prostaglandin analogue (Misoprostol) in order to help prevent peptic ulcers, which may be a side-effect of the NSAIDs.

When H. pylori infection is present, the most effective treatments are combinations of 2 antibiotics (e.g. Clarithromycin, Amoxicillin, Tetracycline, Metronidazole) and 1 proton pump inhibitor (PPI), sometimes together with a bismuth compound. In complicated, treatment-resistant cases, 3 antibiotics (e.g. amoxicillin + clarithromycin + metronidazole) may be used together with a PPI and sometimes with bismuth compound. An effective first-line therapy for uncomplicated cases would be Amoxicillin + Metronidazole + Rabeprazole (a PPI). In the absence of H. pylori, long-term higher dose PPIs are often used.

Treatment of H. pylori usually leads to clearing of infection, relief of symptoms and eventual healing of ulcers. Recurrence of infection can occur and retreatment may be required, if necessary with other antibiotics. Since the widespread use of PPI's in the 1990s, surgical procedures (like "highly selective vagotomy") for uncomplicated peptic ulcers became obsolete.

Perforated peptic ulcer is a surgical emergency and requires surgical repair of the perforation. Most bleeding ulcers require endoscopy urgently to stop bleeding with cautery or injection.

Epidemiology

In Western countries the prevalence of Helicobacter pylori infections roughly matches age (i.e., 20% at age 20, 30% at age 30, 80% at age 80 etc). Prevalence is higher in third world countries. Transmission is by food, contaminated groundwater, and through human saliva (such as from kissing or sharing food utensils.)

According to Mayo Clinic, however, there is no evidence that the infection can be transmitted by kissing.

A minority of cases of Helicobacter infection will eventually lead to an ulcer and a larger proportion of people will get non-specific discomfort, abdominal pain or gastritis.

History

- See also: Timeline of peptic ulcer disease and Helicobacter pylori

John Lykoudis, a general practitioner in Greece, treated patients for peptic ulcer disease with antibiotics, beginning in 1958, long before it was commonly recognized that bacteria were a dominant cause for the disease.[9]

Helicobacter pylori was rediscovered in 1982 by two Australian scientists, J. Robin Warren and Barry J. Marshall as a causative factor for ulcers.[10] In their original paper, Warren and Marshall contended that most stomach ulcers and gastritis were caused by colonization with this bacterium, not by stress or spicy food as had been assumed before.[11]

The H. pylori hypothesis was poorly received, so in an act of self-experimentation Marshall drank a Petri dish containing a culture of organisms extracted from a patient and soon developed gastritis. His symptoms disappeared after two weeks, but he took antibiotics to kill the remaining bacteria at the urging of his wife, since halitosis is one of the symptoms of infection.[12] This experiment was published in 1984 in the Australian Medical Journal and is among the most cited articles from the journal.

In 1997, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, with other government agencies, academic institutions, and industry, launched a national education campaign to inform health care providers and consumers about the link between H. pylori and ulcers. This campaign reinforced the news that ulcers are a curable infection, and that health can be greatly improved and money saved by disseminating information about H. pylori.[13]

In 2005, the Karolinska Institute in Stockholm awarded the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine to Dr. Marshall and his long-time collaborator Dr. Warren "for their discovery of the bacterium Helicobacter pylori and its role in gastritis and peptic ulcer disease". Professor Marshall continues research related to H. pylori and runs a molecular biology lab at UWA in Perth, Western Australia.

It was a previously widely accepted misunderstanding that the use of chewing gum resulted in gastric ulcers. The medical profession believed that this was because the action of masticating on gum caused the over-stimulation of the production of hydrochloric acid in the stomach. The low (acidic) pH (pH 2), or hyperchlorhydria was then believed to cause erosion of the stomach lining in the absence of food, thus causing the development of the gastric ulers.[14]

On the other hand, in the recent past, some believed that natural tree resin extract, mastic gum, actively eliminates the H. pylori bacteria.[15] However, multiple subsequent studies have found no effect of using mastic gum on reducing H. pylori levels.[16][17]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "GI Consult: Perforated Peptic Ulcer". Retrieved on 2007-08-26.

- ↑ Cullen DJ, Hawkey GM, Greenwood DC, et al (1997). "Peptic ulcer bleeding in the elderly: relative roles of Helicobacter pylori and non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs". Gut 41 (4): 459–62. PMID 9391242. PMC: 1891536. http://gut.bmj.com/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=9391242.

- ↑ "Peptic Ulcer: Peptic Disorders: Merck Manual Home Edition". Retrieved on 2007-10-10.

- ↑ For nearly 100 years, scientists and doctors thought that ulcers were caused by stress, spicy food, and alcohol. Treatment involved bed rest and a bland diet. Later, researchers added stomach acid to the list of causes and began treating ulcers with antacids. National Digestive Diseases Information Clearinghouse

- ↑ Cheney G. Rapid (1949). "Healing of peptic ulcers in patients receiving fresh cabbage juice". Calif Med 70 (10): 10–5. PMID 18104715.

- ↑ Wachirawat W, Hanucharurnkul S, Suriyawongpaisal P, et al (2003). "Stress, but not Helicobacter pylori, is associated with peptic ulcer disease in a Thai population". J Med Assoc Thai 86 (7): 672–85. PMID 12948263.

- ↑ Kim YH, Lee JH, Lee SS, et al (2002). "Long-term stress and Helicobacter pylori infection independently induce gastric mucosal lesions in C57BL/6 mice". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 37 (11): 1259–64. PMID 12465722.

- ↑ "ATLAS OF PATHOLOGY". Retrieved on 2007-08-26.

- ↑ Marshall B.J., ed. (2002), "Helicobacter Pioneers: Firsthand accounts from the scientists who discovered helicobacters, 1892–1982", ISBN 0-86793-035-7. Basil Rigas, Efstathios D. Papavasassiliou. John Lykoudis. The general practitioner in Greece who in 1958 discovered the etiology of, and a treatment for, peptic ulcer disease.

- ↑ Marshall B.J. (1983). "Unidentified curved bacillus on gastric epithelium in active chronic gastritis". Lancet 1 (8336): 1273–5. PMID 6134060.

- ↑ Marshall B.J., Warren J.R. (1984). "Unidentified curved bacilli in the stomach patients with gastritis and peptic ulceration". Lancet 1 (8390): 1311–5. doi:. PMID 6145023.

- ↑ Van Der Weyden MB, Armstrong RM, Gregory AT (2005). "The 2005 Nobel Prize in physiology or medicine". Med. J. Aust. 183 (11–12): 612–4. PMID 16336147. http://www.mja.com.au/public/issues/183_11_051205/van11000_fm.html#0_i1091639.

- ↑ Ulcer, Diagnosis and Treatment - CDC Bacterial, Mycotic Diseases

- ↑ Medicine for Nurses (Toohey, 1974)

- ↑ Huwez FU, Thirlwell D, Cockayne A, Ala'Aldeen DA (December 1998). "Mastic gum kills Helicobacter pylori [Letter to the editor, not a peer-reviewed scientific article]". N. Engl. J. Med. 339 (26): 1946. PMID 9874617. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/extract/339/26/1946. Retrieved on 2008-09-06. See also their corrections in the next volume.

- ↑ Loughlin MF, Ala'Aldeen DA, Jenks PJ (February 2003). "Monotherapy with mastic does not eradicate Helicobacter pylori infection from mice". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 51 (2): 367–71. PMID 12562704. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12562704.

- ↑ Bebb JR, Bailey-Flitter N, Ala'Aldeen D, Atherton JC (September 2003). "Mastic gum has no effect on Helicobacter pylori load in vivo". J. Antimicrob. Chemother. 52 (3): 522–3. doi:. PMID 12888582. http://jac.oxfordjournals.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=long&pmid=12888582.

External links

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||