Patriarchy

Patriarchy is the structuring of society on the basis of family units, where fathers have primary responsibility for the welfare of, and authority over, their families. The concept of patriarchy is often used, by extension (in anthropology and feminism, for example), to refer to the expectation that men take primary responsibility for the welfare of the community as a whole, acting as representatives via public office.

The feminine form of patriarchy is matriarchy. However, there are no known examples of matriarchal societies.[1][2]

Contents |

- Further information: Pater familias, Patriarch, Archon, Tribal chief, and Dominus (title)

The word patriarchy entered English in the 16th century, from the post-classical Latin patriarchia "office of a patriarch". It is a loan from Byzantine Greek πατριαρχια "office of a patriarch", in use since the 6th or 7th century for the Christian office, but attested in the 4th century for the headship of a Jewish community, from the Hellenistic Greek term for such a community leader, πατριαρχης.[3]

Greek πατριαρχης "patriarch, community leader" is a compound of πατήρ "father" and -άρχης, from ἀρχός archos "chief" (see arch-, Archon). The Greek -ια suffix forms nominal abstratcs. Greek -αρχ-ια was Latinized as -archia and hence directly English -archy.

The English term is first used in the sense of the societal organization rather than the Church office in the 17th century, by Francis Bacon.[4]

The term patriarch, from post-classical Latin patriarcha "chief or head of a family or tribe", Anglo-Norman patriarche was the title of the bishop of any of the chief sees of the Roman Empire. The Biblical Patriarchs are the heads of the Israelite tribe before Moses. In late medieval use, it could more generically refer to any venerable old man.

The adjective for patriarchy is patriarchal; and patriarchalism, or more commonly paternalism, refer to the practice or defence of patriarchy. Patron is from Latin patronus, and via the use in patron saint came to be used generically (not gender specific) in English. The verb form patronize can be used positively, to describe the activity of patrons, or negatively, to describe adopting a superior attitude. If the superior attitude is adopted by a man, he can be called paternalistic.

Patrimonalism uses the Greek word monos (μόνος, sole) to describe the view of a state as the extended household of a mon-arch (sole ruler, archē as above) or deity. There are records of patrimonalism almost as far back as the earliest writing itself (about 5000 years ago). This is probably because patrimonalism directly facilitated the invention of writing — the first hereditary monarchs gained so much wealth as to need to keep accounts, and enough to pay those accountants. The earliest records of patrimonalism come from Ancient Near Eastern legal documents, the best known being the Code of Hammurabi and the Torah. Some aspects of patrimonalism can still be found in the few remaining monarchies in the world today, for example, British law concerning real estate (see Crown lands), especially in Australia. For more detail regarding patrimonalism see Traditional authority.

Some social customs reflect what is termed patrilineality or patrilocality.

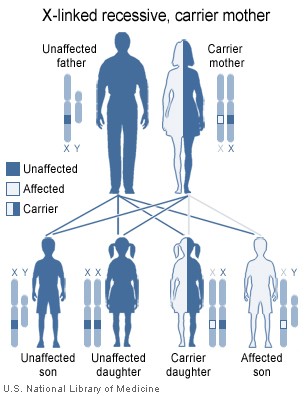

Patrilineal describes customs where family responsibilities and assets pass from father to son. By contrast, contemporary Judaism considers people to be Jewish if their mothers were Jewish, which makes this aspect of contemporary Judaism matrilineal. Biblical Judaism is, however, a classical example of a patrilineal society. Matrilineal is a particularly useful term in genetics, where some genetic features are more or less passed via the maternal line, notably mitochondrial DNA and severe X-linked genetic conditions. An X chromosome from the mother is always passed to offspring, male and female. However, daughters do not receive a Y chromosome, and sons do not receive an X chromosome from their fathers (see sex-determination system, heredity and genetic genealogy).

Patrilocal describes the custom of brides relocating to the geographic community of the husband and his father's family. In a matrilocal society, a husband will relocate to the home community of his wife and her mother (see also marriage). Matrilocality can substantially increase the social influence of women in a culture, however, given that tribal and family leaders are still men in all known matrilocal societies, matrilocality is not equivalent to matriarchy, see main entry patriarchy (anthropology).

By contrast with these other customs, patriarchy can be seen to be distinctly about gender and the nuclear family, gender and public office, and about female-male relationships in general.

Scientific views

Biology

The biology of gender is scientific analysis of the physical basis for behavioural differences between men and women. It is more specific than sexual dimorphism, which covers physical and behavioural differences between males and females of any sexually reproducing species, or sexual differentiation, where physical and behavioural differences between men and women are described. Biological research of gender has explored such areas as: intersex physicalities, gender identity, gender roles and sexual orientation.

It has long been known that there are correlations between the biological sex of animals and their behaviour.[5][6][7] Many of these correlations have been studied in scientific research.

| “ | Genes on the sex chromosomes can directly influence sexual dimorphism in cognition and behaviour, independent of the action of sex steroids. | ” |

Some specific relevant results are as follows. The brains of many animals are significantly different for females and males of the species.[9] Both genes and hormones affect the formation of many animal brains before "birth" (or hatching), and also behaviour of adult individuals. Hormones significantly affect human brain formation, and also brain development at puberty. Both kinds of brain difference affect male and female behaviour.

Brain differences also have a statistically measurable effect on an array of abilities. In particular, on average, women are more capable in nearly everything to do with sensory processing. For an illustrated description of clear differences between female and male brain response to pain see Laura Stanton and Brenna Maloney, 'The Perception of Pain'.[11] On the other hand, male brains seem to be "pushed" towards extremes of low ability or high ability in various forms of mental abstraction, especially those related to space and logic. This means the average scores of young women and men in mathematics, for example, will be close, but there will be more men than women in the very low scores and in the very high scores (see the diagram at the right for an illustration).[10] There is evidence to suggest that forms of autism may be essentially extreme expressions of certain typically male characteristics.[12][13] Hormones have also been linked with male aggression and female power motivation.[14][15] Sarah Blaffer Hrdy (confirming Goldberg above) claims that observed male aggression would predict a tendency towards the patriarchy that has also been observed.[16].

Alexandra M. Lopes and others recently published that:

| “ | A sexual dimorphism in levels of expression in brain tissue was observed by quantitative real-time PCR, with females presenting an up to 2-fold excess in the abundance of PCDH11X transcripts. We relate these findings to sexually dimorphic traits in the human brain. Interestingly, PCDH11X/Y gene pair is unique to Homo sapiens, since the X-linked gene was transposed to the Y chromosome after the human–chimpanzee lineages split.[17] | ” |

Steven Goldberg

To date, feminists have failed to achieve some of their goals (for example, those related to executive positions and average income, see above). This was predicted in 1973 (the early days of second wave feminist activism) by Steven Goldberg (born 1941). "In every society a basic male motivation is the feeling that the women and children must be protected. But the feminist cannot have it both ways: if she wishes to sacrifice all this, all that she will get in return is the right to meet men on male terms. She will lose."[18] Goldberg was chairman of the department of sociology at City College of New York, and has written two books on patriarchy. In the second he wrote:

| “ | There is nothing in this book concerned with the desirability or undesirability of the institutions whose universality the book attempts to explain. For instance, this book is not concerned with the question of whether male domination of hierarchies is morally or politically 'good' or 'bad'. Moral values and political policies, by their nature, consist of more than just empirical facts and their explanation. 'What is' can never entail 'what should be', so science knows nothing of 'should'. 'Answers' to questions of 'should' require subjective elements that science cannot provide. Similarly, there is no implication that one sex is 'superior' in general to the other; 'general superiority' and 'general inferiority' are scientifically meaningless concepts.[19] | ” |

In Goldberg's first book, he seeks an explanation for three specific aspects of male dominance behaviour in human societies. Patriarchy is the first of these. He also considers the phenomenon of male status seeking, which he calls "male attainment." He is influenced by Margaret Mead in identifying this phenomenon. She says, "Men may cook, or weave or dress dolls or hunt hummingbirds, but if such activities are appropriate behavior for men, then the whole society, men and women alike, votes them as important. When the same occupations are performed by women, they are regarded as less important."[20] Finally, he claims that men seem to dominate in one-to-one relationships with women, marriage being one example of such relationships. Goldberg comments, "A woman’s feeling that she must get around a man is the hallmark of male dominance."[21]

Goldberg proposes the hypothesis that the statistical averages of all these forms of behaviour are partly explained by the necessary (but not sufficient) condition of neuroendocrinological effects – namely, testosterone. The title of his first book makes his hypothesis very clear, it was called The Inevitability of Patriarchy: Why the Biological Difference between Men and Women always Produces Male Domination. At the time he wrote (1973), there were only very limited results from biological researchers to support or contradict his hypothesis. The situation has changed a lot since then.

For other writers who make similar points to Goldberg see Steven Pinker and Donald Brown in the literature below.

For current feminists and writers with considerably more biological knowledge than Goldberg, who accept his hypothesis, but consider issues beyond the biological, see Helena Cronin and Louann Brizendine.

| “ | It all stems from muddling science and politics. It's as if people believe that if you don't like what you think are the ideological implications of the science then you're free to reject the science – and to cobble together your own version of it instead. Now, I know that sounds ridiculous when it's spelled out explicitly. Science doesn't have ideological implications; it simply tells you how the world is – not how it ought to be. So, if a justification or a moral judgement or any such 'ought' statement pops up as a conclusion from purely scientific premises, then obviously the thing to do is to challenge the logic of the argument, not to reject the premises. But, unfortunately, this isn't often spelled out. And so, again and again, people end up rejecting the science rather than the fallacy.[22] | ” |

| “ | "To state categorically that there can be no biological component would seem to be foolish. We do not know yet how male hormones (acting indeed before birth and the possibility of different socialization) may affect the male psyche. But that there might be a biological component does not lead me to conclude that men then should do what is 'natural' to them, for there must be complementarity between the sexes. It makes me think that humanity is faced with a deeper problem than we knew." Margaret Daphne Hampson[23] | ” |

Sociology

According to Sanderson, a sociobiologist who notes that Goldberg's theory is "important and rings true", most (non-biological) sociologists reject Goldberg's biological explanation, and and still insist that cultural conditioning is primarily responsible for establishing patriarchy.[24] According to late 20th century western sociological theory, patriarchy is the result of cultural constructions that are passed down from generation to generation.[24]

Issues

Benefits of patriarchy

Patriarchy is advanced as being beneficial for human evolution and social organization on many grounds, crossing several disciplines. Although biology may explain its existence (see below), arguments for its social utility have been made since ancient times. These include elements of Greek Stoic Philosophy and the Roman social structure based on the pater familias,[25] but are also found in Akkadian records of Babylonian and Assyrian laws. George Lakoff proposes an ancient dichotomy of "Strict Father" as opposed to "Nurturing Parent" models of ethical theory (SFM and NPM).[26] In general, the main lines of argument are either pragmatic—namely, the reproductive advantages of male-as-provider—[27] or ethical—that any perceived male authority is contingent upon underlying perceptions of duty of care.

Feminist criticism

The 20th century women's rights movement criticized the social domination of males in modern Western society as unjust. Women's suffrage was introduced in all Western democracies by the end of the 20th century (see Timeline of women's suffrage) and female holders of political office and heads of state became commonplace as a consequence. The Women's Rights movement is also known as First-wave feminism.

Second-wave feminism in the 1960s to 1970s turned to theoretical criticism of patriarchy, and feminist history and feminist archaeology constructed the hypothesis of the patriarchy as a secondary imposition on an originally gynecocentric or matriarchal Urgesellschaft. Tribal societies are not universally patriarchal, and a number of indigenous matrilineal societies with egalitarian structures are on record. This has led to feminist criticism of patriarchy as the result of the hierarchical structure of urban civilization, in the feminist spirituality movement combined with calls to a return to a non-hierarchic model based on paleolithic proto-society.

In some feminist theories, the opposite of feminism is patriarchy. It is not surprising, therefore, that the word patriarchy has a range of additional, negative associations when used in the context of feminist theory, where it is sometimes capitalized and used with the definite article (the Patriarchy), likely best understood as a form of collective personification (compare "blame it on the Government" to "blame it on the Patriarchy"). The use of the word patriarchy in feminist literature has become so loaded with emotive associations that some writers prefer to use an approximate synonym, the more objective and technical androcentric (also from Greek – anēr, genitive andros, meaning man).

Fredrika Scarth, a feminist, reads Simone de Beauvoir's The Second Sex to be saying, "Neither men nor women live their bodies authentically under patriarchy."[28] Mary Daly, a radical feminist, wrote, "Males and males only are the originators, planners, controllers, and legitimators of patriarchy."[29] Carole Pateman, another feminist, writes, "The patriarchal construction of the difference between masculinity and femininity is the political difference between freedom and subjection."[30]

Liberal, or mainstream, feminists do not propose to replace patriarchy with matriarchy, rather they argue for equality. Some radical feminists and separatist feminists have have argued for gendercide against men, matriarchy, or separation.[31] However, Ronald Dworkin has argued that equality is a difficult idea.[32] It is particularly hard to work out what equality means when it comes to gender, because there are real differences between men and women (see Sexual dimorphism and Gender differences). Recent feminist writers speak of "feminisms of diversity", that seek to reconcile older debates between equality feminisms and difference feminisms. For instance, Judith Squires writes, "The whole conceptual force of 'equality' rests on the assumption of differences, which should in some respect be valued equally."[33]

For a leading feminist who writes against patriarchy see Marilyn French; and for one who is more sympathetic see Christina Hoff Sommers.

In summary, some recent feminist writers have shown a tendency to admit misandry among some other members of the movement[34], and acknowledge real differences in men and women that make diversity a more meaningful aim than reductionistic equality (for example Judith Squires above).

Decades of legislation and affirmative action have not yet changed the fact that western culture is male dominated, and that it remains patriarchal, although women can vote in most countries of the world, and they outnumber men in higher education in many countries.[35]

However, heads of state, cabinet ministers, and the top executives of major companies are still mostly men (see glass ceiling). Also, women's average income is still significantly lower than men's average income. However many masculists argue that this is due to education and career choices that women and men make, rather than the patriarchy.[36] Sally Haslanger claims women are still marginalized within academic philosophy departments.[37]

Existence of matriarchies

- See also: Cultures that have been claimed to be matriarchal

Encyclopædia Britannica says matriarchy is a "hypothetical social system".[38] The Britannica article goes on to note, "The view of matriarchy as constituting a stage of cultural development is now generally discredited. Furthermore, the consensus among modern anthropologists and sociologists is that a strictly matriarchal society never existed."[38]

The anthropologist Margaret Mead said, "All the claims so glibly made about societies ruled by women are nonsense. We have no reason to believe that they ever existed. ... men everywhere have been in charge of running the show. ... men have always been the leaders in public affairs and the final authorities at home."[39]

See also

- Anti-feminism

- Chinese patriarchy

- Domitius

- Gender role

- Homemaker

- Masculinity

- Nature versus nurture

- Patriarch magazines

- Patriarchs (Bible)

- Sociology of fatherhood

Notes and references

- ↑ "Once we abandon the concept of women as historical victims, acted upon by violent men, inexplicable 'forces', and societal institutions, we must explain the central puzzle—woman's participation in the construction of the system that subordinates her. I suggest that abandoning the search for an empowering past—the search for matriarchy—is the first step in the right direction. The creation of compensatory myths of the distant past of women will not emancipate women in the present and the future." Gerda Lerner, The Creation of Patriarchy, (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1986), p. 36.

- ↑ Cynthia Eller, The Myth of Matriarchal Prehistory: Why an Invented Past Won't Give Women a Future, (Boston: Beacon Press, 2001).]

- ↑ OED s.v. "patriarchy".

- ↑ "The first [state] is Paternity or Patriarchy, which was when a family growing so great as it could not containe it selfe within one habitation, some branches of the descendents were forced to plant themselves into new families." Concerning the Post-Nati of Scotland (1626), in Three Speeches (1641) (cited after OED).

- ↑ Charles Darwin, On the Origin of Species by Means of Natural Selection, or the Preservation of Favoured Races in the Struggle for Life, (London: John Murray, 1859).

- ↑ Charles Darwin, The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, 2 volumes, (London: John Murray, 1871).

- ↑ Helena Cronin, The Ant and the Peacock: Altruism and Sexual Selection from Darwin to Today, (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1991).

- ↑ Skuse, David H (2006). "Sexual dimorphism in cognition and behaviour: the role of X-linked genes". European Journal of Endocrinology 155: 99–106. doi:.

- ↑ Robert W Goy and Bruce S McEwen, Sexual Differentiation of the Brain: Based on a Work Session of the Neurosciences Research Program. MIT Press Classics. Boston: MIT Press, 1980.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Camilla Persson Benbow and Julian C Stanley, 'Sex Differences in Mathematical Reasoning Ability: More Facts', Science 222 (1983): 1029-1031.

- ↑ Laura Stanton and Brenna Maloney, 'The Perception of Pain', Washington Post 19 December, 2006.

- ↑ Simon Baron-Cohen, 'The Extreme-Male-Brain Theory of Autism', in H Tager-Flusberg (ed.), Neurodevelopmental Disorders, (Boston: The MIT Press, 1999).

- ↑ Simon Baron-Cohen. Mindblindness: An Essay on Autism and Theory of Mind. (Boston: The MIT Press, 1997).

- ↑ Elizabeth J. Susman, Gale Inoff-Germain, Editha D. Nottelmann, and others, 'Hormones, Emotional Dispositions, and Aggressive Attributes in Young Adolescents', Child Development 58 (1987): 1114-1134.

- ↑ http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2008/05/080522075940.htm

- ↑ , 'Raising Darwin's Consciousness: Female Sexuality and the prehominid origins of patriarchy.' Human Nature 8 (1997): 1-49.

- ↑ Alexandra M. Lopes and others,'Inactivation status of PCDH11X: sexual dimorphisms in gene expression levels in brain', Human Genetics 119 (2006): 1–9.

- ↑ Steven Goldberg, The Inevitability of Patriarchy, (London: Temple Smith, 1977), p. 196.

- ↑ Steven Goldberg, Why Men Rule, (Chicago, Illinois: Open Court Publishing Company, 1993), p. 1.

- ↑ Margaret Mead. Male and Female. London: Penguin, 1950.

- ↑ Steven Goldberg, Why Men Rule, (Chicago, Illinois: Open Court Publishing Company, 1993), p. 11.

- ↑ John Brockman, 'Getting Human Nature Right: A Talk with Helena Cronin', Edge 73 (2000): 2.

- ↑ Margaret Daphne Hampson, Theology and Feminism, (Oxford: Blackwell Publishing, 1990), p. x.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 Sanderson, Stephen K. (2001). The Evolution of Human Sociality. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 198.

- ↑ "Research into the nature of marriage in the Greco-Roman world ... shows ... [that] in Stoic traditions marriage promoted the full responsibility of a husband as a householder, father, and citizen and stability in society." Anthony C. Thiselton, First Corinthians: A Shorter Exegetical and Pastoral Commentary, (Grand Rapids: Wm. B. Eerdmans Publishing Co., 2006), p. 102.

- ↑ George Lakoff, Moral Politics, (Univ of Chicago Press, 1996) and Philosophy in the Flesh, (UCP, 1999).

- ↑ Phillip Longman, 'The Return of Patriarchy', Foreign Policy, 2006.

- ↑ Fredrika Scarth, The Other Within: Ethics, Politics and the Body in Simone de Beauvoir, (Oxford: Rowman & Littlefield, 2004), p. 100.

- ↑ Mary Daly, Gyn/Ecology The Metaethics of Radical Feminism, (Boston: Beacon Press, 1978), p. 29.

- ↑ Carole Pateman, The Sexual Contract, (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1988), p. 207.

- ↑ http://www.wie.org/j16/daly.asp?page=2

- ↑ "People who praise it or disparage it disagree about what they are praising or disparaging.", Ronald Dworkin, Sovereign Virtue: The Theory and Practice of Equality, (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2000), p. 2.

- ↑ Judith Squires, Gender in Political Theory, (Cambridge: Polity Press, 1999), p. 97.

- ↑ Hoff Sommers, Christina, Who Stole Feminism? How Women Have Betrayed Women (Touchstone/Simon & Schuster, 1995)

- ↑ "In terms of academic achievement, international education figures from 43 developed countries, published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development in 2003, showed a consistent picture of women achieving better results than men at every level, particularly in literacy assessments.", Ian W Craig, Emma Harper and Caroline S Loat, 'The Genetic Basis for Sex Differences in Human Behaviour: Role of the Sex Chromosomes', Annals of Human Genetics 68 (2004): 269–284.

- ↑ http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2007/04/02/AR2007040201262.html

- ↑ Sally Haslanger, Article Title.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 'Matriarchy', Encyclopædia Britannica, 2007.

- ↑ Margaret Mead,'Review of Sex and Temperament in Three Privative Societies'. Redbook (October 1973): 48.

Bibliography

- Adeline, Helen B. Fascinating Womanhood. New York: Random House, 2007.

- Baron-Cohen, Simon. The Essential Difference: The Truth about the Male and Female Brain. New York: Perseus Books Group, 2003.

- Beauvoir, Simone de. Le Deuxième Sexe. Paris: Éditions Gallimard, 1949. (original French edition)

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. London: Jonathan Cape, 1953. (first UK edition, in translation)

- Beauvoir, Simone de. The Second Sex. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1953. (first USA edition, in translation)

- Bourdieu, Pierre. Masculine Domination. Translated by Richard Nice. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2001.

- Brizendine, Louann. The Female Brain. New York: Morgan Road Books, 2006.

- Brown, Donald E. Human Universals. New York: McGraw Hill, 1991.

- Jay, Jennifer W. 'Imagining Matriarchy: "Kingdoms of Women" in Tang China'. Journal of the American Oriental Society 116 (1996): 220-229.

- Konner, Melvin. The Tangled Wing: Biological Constraints on the Human Spirit. 2nd edition, revised and updated. (Owl Books, 2003). 560p. ISBN 0805072799 [first published 1982, Endnotes

- Lepowsky, Maria. Fruit of the Motherland: Gender in an Egalitarian Society. New York: Columbia University Press, 1993.

- Mead, Margaret. 'Do We Undervalue Full-Time Wives'. Redbook 122 (1963).

- Mies, Maria. Patriarchy and Accumulation on a World Scale: Women in the International Division of Labour. Palgrave MacMillan, 1999.

- Moir, Anne and David Jessel. Brain Sex: The Real Difference Between Men and Women.

- Ortner, Sherry Beth. 'Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?'. In MZ Rosaldo and L Lamphere (eds). Woman, Culture and Society. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1974, pp. 67-87.

- Ortner, Sherry Beth. 'So, Is Female to Male as Nature is to Culture?'. In S Ortner. Making Gender: The Politics and Erotics of Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1996, pp. 173-180.

- Pilcher, Jane and Imelda Wheelan. 50 Key Concepts in Gender Studies. London: Sage Publications, 2004.

- Pinker, Steven. The Blank Slate: A Modern Denial of Human Nature. London: Penguin Books, 2002.

External links

- 'Matriarchy'. Encyclopædia Britannica Online, 2007.

- 'Cattle ownership makes it a man's world'. New Scientist (2003).

- Mary Wollstonecraft. A Vindication of the Rights of Women. Boston: Peter Edes for Thomas and Andrews, 1792.

- Simone de Beauvoir. The Second Sex. Translated by HM Parshley. London: Penguin, 1972.

- 'Equality'. In Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Stanford University, 2001.

- Times Literary Supplement review (by Mark Ridley) of The Inevitability of Patriarchy and reply by the author (Steven Goldberg).

- Phyllis M Kaberry. A Study of the Economic Position of Women in Bamenda, British Cameroons. London: Her Majesty's Stationary Office, 1952.

- Steven Webster. 'Was it Matriarchy?' New York Review of Books (1972): 37–38.

- Phillip Longman. 'The Return of Patriarchy'. Foreign Policy (2006).

- Official site of the Council on Biblical Manhood and Womanhood.

- Culture, Society & Masculinities — Men's Studies Press.

- Beyond Ritual: Rethinking the Role of Patriarchy in African Traditional Religions.

|

||||||||