Particulate

| Air pollution |

| Acid rain • Air Quality Index • Atmospheric dispersion modeling • Chlorofluorocarbon • Global dimming • Global distillation• Global warming • Indoor air quality • Ozone depletion • Particulate • Smog |

| Water pollution |

| Eutrophication • Hypoxia • Marine pollution • Marine debris • Ocean acidification • Oil spill • Ship pollution • Surface runoff • Thermal pollution • Wastewater • Waterborne diseases • Water quality • Water stagnation • |

| Soil contamination |

| Bioremediation • Electrical resistance heating • Herbicide • Pesticide • Soil Guideline Values (SGVs) |

| Radioactive contamination |

| Actinides in the environment • Environmental radioactivity • Fission product • Nuclear fallout • Plutonium in the environment • Radiation poisoning • Radium in the environment • Uranium in the environment |

| Other types of pollution |

| Invasive species • Light pollution • Noise pollution • Radio spectrum pollution • Visual pollution |

| Inter-government treaties |

| Montreal Protocol • Kyoto Protocol • CLRTAP • OSPAR • Stockholm Convention |

| Major organizations |

| DEFRA • EPA • Global Atmosphere Watch • EEA • Greenpeace • American Lung Association |

| Related topics |

| Environmental Science • Natural environment • Acid Rain Program |

Particulates, alternatively referred to as particulate matter (PM) or fine particles, are tiny particles of solid or liquid suspended in a gas. In contrast, aerosol refers to particles and the gas together. Sources of particulate matter can be man made or natural. Some particulates occur naturally, originating from volcanoes, dust storms, forest and grassland fires, living vegetation, and sea spray. Human activities, such as the burning of fossil fuels in vehicles, power plants and various industrial processes also generate significant amounts of aerosols. Averaged over the globe, anthropogenic aerosols—those made by human activities—currently account for about 10 percent of the total amount of aerosols in our atmosphere. Increased levels of fine particles in the air are linked to health hazards such as heart disease, altered lung function and lung cancer.

Contents |

Scale classification

Among the most common categorizations imposed on particulates are those with respect to size, referred to as fractions. As particles are often non-spherical (for example, Asbestos fibers), there are many definitions of particle size. The most widely used definition is the aerodynamic diameter. A particle with an aerodynamic diameter of 10 micrometers moves in a gas like a sphere of unit density (1 gram per cubic centimeter) with a diameter of 10 micrometers. PM diameters range from less than 10 nanometers to more than 10 micrometers. These dimensions represent the continuum from a few molecules up to the size where particles can no longer be carried by a gas.

The notation PM10 is used to describe particles of 10 micrometers or less and PM2.5 represents particles less than 2.5 micrometers in aerodynamic diameter. [1].

But because no sampler is perfect in the sense that no particle larger than its cutoff diameter passes the inlet, all reference methods allow a high margin of error. These are also sometimes referred to with other equivalent numeric values. Everything below 100 nm, down to the size of individual molecules is classified as ultrafine particles (UFP or UP)[2].

| fraction | size range |

|---|---|

| PM10 (thoracic fraction) | <=10 μm |

| PM2.5 (respirable fraction) | <=2.5 μm |

| PM1 | <=1 μm |

| Ultrafine (UFP or UP) | <=0.1 μm |

| PM10-PM2.5 (coarse fraction) | 2.5 μm - 10 μm |

Note that PM10-PM2.5 is the difference of PM10 and PM2.5, so that it only includes the coarse fraction of PM10.

These are the formal definitions. Depending on the context, alternative definitions may be applied. In some specialized settings, each fraction may exclude the fractions of lesser scale, so that PM10 excludes particles in a smaller size range, e.g. PM2.5, usually reported separately in the same work [2]. Such a case is sometimes emphasized with the difference notation, e.g. PM10-PM2.5. Other exceptions may be similarly specified. This is useful when not only the upper bound of a fraction is relevant to a discussion. The facts that some particle size ranges require greater filter strength and the smallest ones can outstrip the body's ability to keep them out of cells both serve to guide understanding of related public policy, environment, and health topics.

Sources

There are both natural and human sources of atmospheric particulates. The biggest natural sources are dust, volcanoes, and forest fires. Sea spray is also a large source of particles though most of these fall back to the ocean close to where they were emitted. The biggest human sources of particles are combustion sources, mainly the burning of fuels in internal combustion engines in automobiles and power plants, and wind blown dust from construction sites and other land areas where the water or vegetation has been removed. Some of these particles are emitted directly to the atmosphere (primary emissions) and some are emitted as gases and form particles in the atmosphere (secondary emissions).

Composition

The composition of aerosol particles depends on their source. Wind-blown mineral dust [1] tends to be made of mineral oxides and other material blown from the Earth's crust; this aerosol is light-absorbing. Sea salt [2] is considered the second-largest contributor in the global aerosol budget, and consists mainly of sodium chloride originated from sea spray; other constituents of atmospheric sea salt reflect the composition of sea water, and thus include magnesium, sulfate, calcium, potassium, etc. In addition, sea spray aerosols may contain organic compounds, which influence their chemistry. Sea salt does not absorb.

Secondary particles derive from the oxidation of primary gases such as sulfur and nitrogen oxides into sulfuric acid (liquid) and nitric acid (gaseous). The precursors for these aerosols—i.e. the gases from which they originate—may have an anthropogenic origin (from fossil fuel combustion) and a natural biogenic origin. In the presence of ammonia, secondary aerosols often take the form of ammonium salts; i.e. ammonium sulfate and ammonium nitrate (both can be dry or in aqueous solution); in the absence of ammonia, secondary compounds take an acidic form as sulfuric acid (liquid aerosol droplets) and nitric acid (atmospheric gas). Secondary sulfate and nitrate aerosols are strong light-scatterers. [3] This is mainly because the presence of sulfate and nitrate causes the aerosols to increase to a size that scatters light effectively.

Organic matter (OM) can be either primary or secondary, the latter part deriving from the oxidation of VOCs; organic material in the atmosphere may either be biogenic or anthropogenic. Organic matter influences the atmospheric radiation field by both scattering and absorption. Another important aerosol type is constitude of elemental carbon (EC, also known as black carbon, BC): this aerosol type includes strongly light-absorbing material and is thought to yield large positive radiative forcing. Organic matter and elemental carbon together constitute the carbonaceous fraction of aerosols.ii[4]

The chemical composition of the aerosol directly affects how it interacts with solar radiation. The chemical constituents within the aerosol change the overall refractive index. The refractive index will determine how much light is scattered and absorbed.

Removal processes

In general, the smaller and lighter a particle is, the longer it will stay in the air. Larger particles (greater than 10 micrometers in diameter) tend to settle to the ground by gravity in a matter of hours whereas the smallest particles (less than 1 micrometer) can stay in the atmosphere for weeks and are mostly removed by precipitation. Diesel particulate matter is of course highest near the source of emission. Any info regarding DPM and the atmosphere, flora, height, and distance from major sources would be useful to determine health effects.

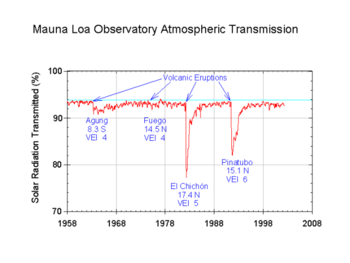

Radiative forcing from aerosols

Aerosols, natural and anthropogenic, can affect the climate by changing the way radiation is transmitted through the atmosphere. Direct observations of the effects of aerosols are quite limited so any attempt to estimate their global effect necessarily involves the use of computer models. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, IPCC, says: While the radiative forcing due to greenhouse gases may be determined to a reasonably high degree of accuracy... the uncertainties relating to aerosol radiative forcings remain large, and rely to a large extent on the estimates from global modelling studies that are difficult to verify at the present time [5].

A graphic showing the contributions (at 2000, relative to pre-industrial) and uncertainties of various forcings is available here.

Sulfate aerosol

Sulfate aerosol has two main effects, direct and indirect. The direct effect, via albedo, is to cool the planet: the IPCC's best estimate of the radiative forcing is -0.4 watts per square meter with a range of -0.2 to -0.8 W/m² [6] but there are substantial uncertainties. The effect varies strongly geographically, with most cooling believed to be at and downwind of major industrial centres. Modern climate models attempting to deal with the attribution of recent climate change need to include sulfate forcing, which appears to account (at least partly) for the slight drop in global temperature in the middle of the 20th century. The indirect effect (via the aerosol acting as cloud condensation nuclei, CCN, and thereby modifying the cloud properties -albedo and lifetime-) is more uncertain but is believed to be a cooling.

Black carbon

Black carbon (BC), or carbon black, or elemental carbon (EC), often called soot, is composed of pure carbon clusters, skeleton balls and buckyballs, and is one of the most important absorbing aerosol species in the atmosphere. It should be distinguished from organic carbon (OC): clustered or aggregated organic molecules on their own or permeating an EC buckyball. BC from fossil fuels is estimated by the IPCC in the Fourth Assessment Report of the IPCC, TAR, to contribute a global mean radiative forcing of +0.2 W/m² (was +0.1 W/m² in the Second Assessment Report of the IPCC, SAR), with a range +0.1 to +0.4 W/m².

All aerosols both absorb and scatter solar and terrestrial radiation. If a substance absorbs a significant amount of radiation, as well as scattering, it is called absorbing. This is quantified in the Single Scattering Albedo (SSA), the ratio of scattering alone to scattering plus absorption (extinction) of radiation by a particle. The SSA tends to unity if scattering dominates, with relatively little absorption, and decreases as absorption increases, becoming zero for infinite absorption. For example, sea-salt aerosol has an SSA of 1, as a sea-salt particle only scatters, whereas soot has an SSA of 0.23, showing that it is a major atmospheric aerosol absorber.

Health effects

The effects of inhaling particulate matter has been widely studied in humans and animals and include asthma, lung cancer, cardiovascular issues, and premature death. The size of the particle is a main determinant of where in the respiratory tract the particle will come to rest when inhaled. Because of the size of the particle, they can penetrate the deepest part of the lungs.[3] Larger particles are generally filtered in the nose and throat and do not cause problems, but particulate matter smaller than about 10 micrometers, referred to as PM10, can settle in the bronchi and lungs and cause health problems. The 10 micrometer size does not represent a strict boundary between respirable and non-respirable particles, but has been agreed upon for monitoring of airborne particulate matter by most regulatory agencies. Similarly, particles smaller than 2.5 micrometers, PM2.5, tend to penetrate into the gas-exchange regions of the lung, and very small particles (< 100 nanometers) may pass through the lungs to affect other organs. In particular, a study published in the Journal of the American Medical Association indicates that PM2.5 leads to high plaque deposits in arteries, causing vascular inflammation and atherosclerosis — a hardening of the arteries that reduces elasticity, which can lead to heart attacks and other cardiovascular problems [4]. Researchers suggest that even short-term exposure at elevated concentrations could significantly contribute to heart disease.

Researchers at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health have conducted the largest nationwide study on the acute health effects of coarse particle pollution. Coarse particles are airborne pollutants that fall between 2.5 and 10 micrometers in diameter. [5] The study, published in the May 14, 2008, edition of JAMA, found evidence of an association with hospital admissions for cardiovascular diseases but no evidence of an association with the number of hospital admissions for respiratory diseases. After taking into account fine particle levels, the association with coarse particles remained but was no longer statistically significant.

The smallest particles, less than 100 nanometers (nanoparticles), may be even more damaging to the cardiovascular system.[6] There is evidence that particles smaller than 100 nanometers can pass through cell membranes and migrate into other organs, including the brain. It has been suggested that particulate matter can cause similar brain damage as that found in Alzheimer patients. Particles emitted from modern diesel engines (commonly referred to as Diesel Particulate Matter, or DPM) are typically in the size range of 100 nanometers (0.1 micrometer). In addition, these soot particles also carry carcinogenic components like benzopyrenes adsorbed on their surface. It is becoming increasingly clear that the legislative limits for engines, which are in terms of emitted mass, are not a proper measure of the health hazard. One particle of 10 µm diameter has approximately the same mass as 1 million particles of 100 nm diameter, but it is clearly much less hazardous, as it probably never enters the human body - and if it does, it is quickly removed. Proposals for new regulations exist in some countries, with suggestions to limit the particle surface area or the particle number.

The large number of deaths and other health problems associated with particulate pollution was first demonstrated in the early 1970s [7] and has been reproduced many times since. PM pollution is estimated to cause 22,000-52,000 deaths per year in the United States (from 2000) [8] and 200,000 deaths per year in Europe.

Climate effects

Climate effects can be extremely catastrophic; sulfur dioxide ejected from the eruption of Huaynaputina probably caused the Russian famine of 1601 - 1603, leading to the deaths of two million.

Regulation

Due to the health effects of particulate matter, maximum standards have been set by various governments. Many urban areas in the U.S. and Europe still frequently violate the particulate standards, though urban air on these continents has become cleaner, on average, with respect to particulates over the last quarter of the 20th century. Much of the developing world, especially Asia, exceed standards by such a wide margin that even brief visits to these places may be unhealthful.

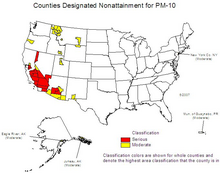

United States

The United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) sets standards for PM10 and PM2.5 concentrations in urban air. (See National Ambient Air Quality Standards.) EPA regulates primary particulate emissions and precursors to secondary emissions (NOx, sulfur, and ammonia).

EU legislation

In directives 1999/30/EC and 96/62/EC, the European Commission has set limits for PM10 in the air:

| Phase 1 from 1 January 2005 |

Phase 2¹ from 1 January 2010 |

|

|---|---|---|

| Yearly average | 40 µg/m³ | 20 µg/m³ |

| Daily average (24-hour) allowed number of exceedences per year. |

50 µg/m³ 35 |

50 µg/m³ 7 |

¹ indicative value.

Affected areas

| Most Polluted World Cities by PM[9] | |

|---|---|

| Particulate matter, μg/m3 (2004) |

City |

| 169 | Cairo, Egypt |

| 150 | Delhi, India |

| 128 | Kolkata, India (Calcutta) |

| 125 | Tianjin, China |

| 123 | Chongqing, China |

| 109 | Kanpur, India |

| 109 | Lucknow, India |

| 104 | Jakarta, Indonesia |

| 101 | Shenyang, China |

The most concentrated particulate matter pollution tends to be in densely populated metropolitan areas in developing countries. The primary cause is the burning of fossil fuels by transportation and industrial sources.

- Particulate matter studies in Bangkok Thailand indicated a 1.9% increased risk of dying from cardiovascular disease, and 1.0% risk of all disease for every 10 micrograms per cubic meter. Levels averaged 65 in 1996, 68 in 2002, and 52 in 2004. Decreasing levels may be attributed to conversions of diesel to natural gas combustion as well as improved regulations[10]

|

|

|

|

U.S. counties violating national PM2.5 standards, roughly correlated with population density.

|

U.S. counties violating national PM10 standards.

|

Aerosol science

The field of aerosol science and technology has grown in response to the need to understand and control natural and manmade aerosols.

References

- ↑ ""Glossary: P"". "Terms of Environment: Glossary, Abbreviations and Acronyms; ". US EPA. Retrieved on 2007-11-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 ""A Review of the Measurement, Emission, Particle Characteristics and Potential Human Health Impacts of Ultrafine Particles: Characterization of Ultrafine Particles"". PubH 5103; Exposure to Environmental Hazards; Fall Semester 2003 course material. University of Minnesota (2003). Retrieved on 2007-11-03.

- ↑ Region 4: Laboratory and Field Operations - PM 2.5 (2008).PM 2.5 Objectives and History. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

- ↑ Pope, C Arden; et al. (2002). "Cancer, cardiopulmonary mortality, and long-term exposure to fine particulate air pollution". J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 287: 1132–1141. doi:. PMID 11879110. http://jama.ama-assn.org/cgi/reprint/287/9/1132.

- ↑ Newswise: National Study Examines Health Risks of Coarse Particle Pollution

- ↑ Bloomberg.com: News

- ↑ Lave, Lester B.; Eugene P. Seskin (1973). "An Analysis of the Association Between U.S. Mortality and Air Pollution". J. Amer. Statistical Association 68: 342.

- ↑ Mokdad, Ali H.; et al. (2004). "Actual Causes of Death in the United States, 2000". J. Amer. Med. Assoc. 291 (10): 1238.

- ↑ http://siteresources.worldbank.org/DATASTATISTICS/Resources/table3_13.pdf

- ↑ Health Effects of Air Pollution in Bangkok

Further reading

- Article at earthobservatory.nasa.gov describing the possible influence of aerosols on the climate

- The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (the principal international scientific body on climate change) chapter on atmospheric aerosols and their radiative effects

- [7] InsideEPA.com, Study Links Air Toxics To Heart Disease In Mice Amid EPA Controversy

- Preining, Othmar and E. James Davis (eds.), "History of Aerosol Science," Österreichische Akademie der Wissenschaften, ISBN 3700129157 (pbk.)

- G Invernizzi et al., Particulate matter from tobacco versus diesel car exhaust: an educational perspective. Tobacco Control 13, S.219-221 (2004)

- Sheldon K.Friedlander, "Smoke, Dust and Haze".

- JEFF CHARLTON Pandemic planning: a review of respirator and mask protection levels.

- Hinds, William C., Aerosol Technology: Properties, Behavior, and Measurement of Airborne Particles, Wiley-Interscience, ISBN 0471194107

See also

- Adequately wet

- Aerosol science

- Air pollution

- Biological warfare

- Clouds

- Criteria air contaminants

- Deposition

- Diesel particulate matter

- Dust

- Fog

- Global dimming

- Global warming

- Global Atmosphere Watch

- Haze

- Medical geology

- National Ambient Air Quality Standards (USA)

- Particulate mask

- "Pea soup" fog

- Pollution

- Radiological weapon

- Respirator

- Scrubber

External links

- National Pollutant Inventory - Particulate matter fact sheet

- WHO-Europe reports: Health Aspects of Air Pollution (2003) (PDF) and "Answer to follow-up questions from CAFE (2004) (PDF)

- American Association for Aerosol Research

- Particulate Air Pollution

- Aerosol Society - The Development of Aerosol Science in the United Kingdom

- Watch and read 'Dirty Little Secrets', 2006 Australian science documentary on health effects of fine particle pollution from vehicle exhausts

- Aerosol Science and Technology

- Canada-Wide Standards

- Little Green Data Book 2007, World Bank. Lists C02 and PM statistics by country.

- Air Pollution in World Cities (PM10 Concentrations)

- European Environment Agency