Pancreatic cancer

| Pancreatic cancer Classification and external resources |

|

|

|

|---|---|

| ICD-10 | C25. |

| ICD-9 | 157 |

| OMIM | 260350 |

| DiseasesDB | 9510 |

| MedlinePlus | 000236 |

| eMedicine | med/1712 |

| MeSH | D010190 |

Pancreatic cancer is a malignant tumor of the pancreas. Each year about 37,680 individuals in the United States are diagnosed with this condition, and 34,290 die from the disease. In Europe more than 60,000 are diagnosed each year. Depending on the extent of the tumor at the time of diagnosis, the prognosis is generally regarded as poor, with less than 5 percent of those diagnosed still alive five years after diagnosis, and complete remission still extremely rare.[1] About 95 percent of pancreatic tumors are adenocarcinomas (M8140/3). The remaining 5 percent include other tumors of the exocrine pancreas (e.g., serous cystadenomas), acinar cell cancers, and pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors (such as insulinomas, M8150/1, M8150/3). These tumors have a completely different diagnostic and therapeutic profile, and generally a more favorable prognosis.[1]

Contents |

Signs and symptoms

Presentation

Pancreatic cancer is sometimes called a "silent disease" because early pancreatic cancer often does not cause symptoms,[2] and the later symptoms are usually non-specific and varied.[2] Common symptoms include:

- pain in the upper abdomen that typically radiates to the back[2] and is relieved by leaning forward (seen in carcinoma of the body or tail of the pancreas);

- loss of appetite(anorexia), and/or nausea and vomiting;[2]

- significant weight loss;

- painless jaundice (yellow skin/eyes, dark urine)[2] related to bile duct obstruction (carcinoma of the head of the pancreas). This may also cause acholic stool and steatorrhea.

All of these symptoms can have multiple other causes. Therefore, pancreatic cancer is often not diagnosed until it is advanced.[2]

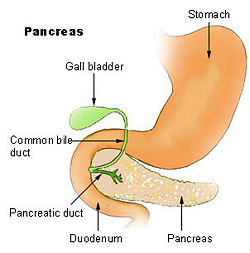

Jaundice occurs when the tumor grows and obstructs the common bile duct, which runs partially through the head of the pancreas. Tumors of the head of the pancreas (approximately 60% of cases) are more likely to cause jaundice by this mechanism.

Trousseau sign, in which blood clots form spontaneously in the portal blood vessels, the deep veins of the extremities, or the superficial veins anywhere on the body, is sometimes associated with pancreatic cancer.

Clinical depression has been reported in association with pancreatic cancer, sometimes presenting before the cancer is diagnosed. However, the mechanism for this association is not known.[3]

Predisposing factors

Risk factors for pancreatic cancer include: [4][2]

- Age (particularly over 60)[2]

- Male gender

- African-American ethnicity[2]

- Smoking. Cigarette smoking nearly doubles one's risk, and the risk persists for at least a decade after quitting. [5]

- Diets low in vegetables and fruits

- Diets high in red meat[6]

- Obesity[7]

- Diabetes mellitus

- Chronic pancreatitis has been linked, but is not known to be causal

- Helicobacter pylori infection

- Family history, 5-10% of pancreatic cancer patients have a family history of pancreatic cancer. The genes responsible for most of this clustering in families have yet to be identified. Pancreatic cancer has been associated with the following syndromes; autosomal recessive ataxia-telangiectasia and autosomal dominantly inherited mutations in the BRCA2 gene, Peutz-Jeghers syndrome due to mutations in the STK11 tumor suppressor gene, hereditary non-polyposis colon cancer (Lynch syndrome), familial adenomatous polyposis, and the familial atypical multiple mole melanoma-pancreatic cancer syndrome (FAMMM-PC) due to mutations in the CDKN2A tumor suppressor gene.[8][1]

- Gingivitis or periodontal disease.[9]

- Alcohol might be a risk factor – see Pancreatic cancer section in Alcohol and cancer

Diagnosis

History — Most patients with pancreatic cancer experience pain, weight loss, or jaundice.[10]

Pain is present in 80 to 85 percent of patients with locally advanced or advanced metastic disease. The pain is usually felt in the upper abdomen as a dull ache that radiates straight through to the back. It may be intermittent and made worse by eating. Weight loss can be profound; it can be associated with anorexia, early satiety, diarrhea, or steatorrhea. Jaundice is often accompanied by pruritus and dark urine. Painful jaundice is present in approximately one-half of patients with locally unresectable disease, while painless jaundice is present in approximately one-half of patients with a potentially resectable and curable lesion. The initial presentation varies according to tumor location. Tumors in the pancreatic body or tail usually present with pain and weight loss, while those in the head of the gland typically present with steatorrhea, weight loss, and jaundice. The recent onset of atypical diabetes mellitus, a history of recent but unexplained thrombophlebitis (Trousseau's sign), or a previous attack of pancreatitis are sometimes noted. Courvoisier sign defines the presence of jaundice and a painlessly distended gallbladder as strongly indicative of pancreatic cancer, and may be used to distinguish pancreatic cancer from gallstones.

Pancreatic cancer is usually discovered during the course of the evaluation of aforementioned symptoms. Liver function tests can show a combination of results indicative of bile duct obstruction (raised conjugated bilirubin, γ-glutamyl transpeptidase and alkaline phosphatase levels). CA19-9 (carbohydrate antigen 19.9) is a tumor marker that is frequently elevated in pancreatic cancer. However, it lacks sensitivity and specificity. When a cutoff above 37 U/mL is used, this marker has a sensitivity of 77% and specificity of 87% in discerning benign from malignant disease. CA 19-9 might be normal early in the course, and could be elevated due to benign causes of biliary obstruction.[11]

Imaging studies, such as ultrasound or abdominal CT, can be used to identify tumors. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is another procedure that can help visualize the tumor and obtain tissue to establish the diagnosis. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography (ERCP) is also used.

Treatment

Surgery

Treatment of pancreatic cancer depends on the stage of the cancer.[12] The Whipple procedure is the most common surgical treatment for cancers involving the head of the pancreas. It can only be performed if the patient is likely to survive major surgery, and if the tumor is localised without invading local structures or metastasizing. It can therefore only be performed in the minority of cases. Recent advances have made possible resection (surgical removal) of tumors that were previously unresectable due to blood vessel involvement.

Tumors of the tail of the pancreas can be resected using a procedure known as a distal pancreatectomy.[13] Recently localized tumors of the pancreas have been resected using minimally invasive (laparoscopic) approaches.

After surgery, adjuvant chemotherapy with gemcitabine may be offered to eliminate whatever tumor tissue may remain in the body. This has been shown to increase 5-year survival rates. Addition of radiation therapy is a hotly debated topic, with groups in the US often favoring the use of adjuvant radiation therapy, while groups in Europe do not.[14]

Surgery can be performed for palliation, if the tumor is invading or compressing the duodenum or colon. In that case, bypass surgery might overcome the obstruction and improve quality of life, but it is not intended as a cure.

Chemotherapy

In patients not suitable for resection with curative intent, palliative chemotherapy may be used to improve quality of life and gain a modest survival benefit. Gemcitabine was approved by the US FDA in 1998 after a clinical trial reported improvements in quality of life in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. This marked the first FDA approval of a chemotherapy drug for a non-survival clinical trial endpoint. Gemcitabine is administered intravenously on a weekly basis. Addition of oxaliplatin (Gem/Ox) conferred benefit in small trials, but is not yet standard therapy.[15] Fluorouracil (5FU) may also be included.

On the basis of a Canadian led Phase III Randomised Controlled trial involving 569 patients with advanced pancreatic cancer, the US FDA has licensed the use of erlotinib (Tarceva) in combination with gemcitabine as a palliative regimen for pancreatic cancer. This trial compared the action of gemcitabine/erlotinib vs gemcitabine/placebo and demonstrated improved survival rates, improved tumor response and improved progression-free survival rates. The survival improvement with the combination is on the order of less than four weeks, leading some cancer experts to question the incremental value of adding erlotinib to gemcitabine treatment. New trials are now investigating the effect of the above combination in the adjuvant and neoadjuvant setting.[16] A trial of anti-angiogenesis agent bevacizumab (Avastin) as an addition to chemotherapy has shown no improvement in survival of patients with advanced pancreatic cancer. It may cause higher rates of high blood pressure, bleeding in the stomach and intestine, and intestinal perforations.

Nutritional Supplements

A phase II clinical trial studying the effect of curcumin on pancreatic cancer was completed in 2007 and the results were published in 2008. The study used 8 grams per day in 21 patients and stopped treatment if the tumor size increased. The conclusion of the study was "Oral curcumin is well tolerated and, despite its limited absorption, has biological activity in some patients with pancreatic cancer."[17][18]

Prognosis

Patients diagnosed with pancreatic cancer typically have a poor prognosis partly because the cancer usually causes no symptoms early on, leading to locally advanced or metastatic disease at time of diagnosis. Median survival from diagnosis is around 3 to 6 months; 5-year survival is less than 5%.[19] With 37,170 cases diagnosed in the United States in 2007, and 33,700 deaths, pancreatic cancer has one of the highest fatality rates of all cancers and is the fourth highest cancer killer in the United States among both men and women. Although it accounts for only 2.5% of new cases, pancreatic cancer is responsible for 6% of cancer deaths each year.[20]

Pancreatic cancer may occasionally result in diabetes. Insulin production is hampered and it has been suggested that the cancer can also prompt the onset of diabetes and vice versa.[21] Thus diabetes is both a risk factor for the development of pancreatic cancer and diabetes can be an early sign of the disease in the elderly.

Prevention

According to the American Cancer Society, there are no established guidelines for preventing pancreatic cancer, although cigarette smoking is responsible for 20-30% of pancreatic cancers.[22]

The ACS recommends keeping a healthy weight, and increasing consumption of fruits, vegetables, and whole grains while decreasing red meat intake, although there is no consistent evidence that this will prevent or reduce pancreatic cancer specifically.[23][24] In 2006 a large prospective cohort study of over 80,000 subjects failed to prove a definite association.[25] The evidence in support of this lies mostly in small case-control studies.

In September 2006, a long-term study concluded that taking Vitamin D can substantially cut the risk of pancreatic cancer (as well as other cancers) by up to 50%.[26][27][28]

Several studies, including one published on 1 June 2007, indicate that B vitamins such as B12, B6, and folate, can reduce the risk of pancreatic cancer when consumed in food, but not when ingested in vitamin tablet form.[29][30]

Awareness

- November is Pancreatic Cancer Awareness Month

- Purple is the traditional color chosen to represent pancreatic cancer awareness.

- The National Cancer Institute’s cancer research budget was $4.824 billion in 2004, an estimated $52.7 million of which was devoted to pancreatic cancer.[31]

- Research spending per pancreatic cancer patient is $1145, the lowest of any leading cancer.[31]

- For a list of pancreatic cancer survivors see Category:Pancreatic cancer survivors.

- The Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN) was created as an advocacy group for pancreatic cancer.

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Ghaneh P, Costello E, Neoptolemos JP (2007). "Biology and management of pancreatic cancer". Gut 56 (8): 1134–52. doi:. PMID 17625148.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 2.7 2.8 "What You Need To Know About Cancer of the Pancreas - National Cancer Institute" (2002-09-16). Retrieved on 2007-12-22.

- ↑ Carney CP, Jones L, Woolson RF, Noyes R Jr, Doebbeling BN. Relationship between depression and pancreatic cancer in the general population. Psychosom Med 2003;65:884-8. PMID 14508036.

- ↑ "ACS :: What Are the Risk Factors for Cancer of the Pancreas?". Retrieved on 2007-12-13.

- ↑ Iodice S, Gandini S, Maisonneuve P, Lowenfels AB (2008). "Tobacco and the risk of pancreatic cancer: a review and meta-analysis". Langenbecks Arch Surg 393: 535. doi:. PMID 18193270.

- ↑ "Red Meat May Be Linked to Pancreatic Cancer". Journal of the National Cancer Institute. WebMD (2005-10-05). Retrieved on 2008-03-05.

- ↑ "Obesity Linked to Pancreatic Cancer". American Cancer Society. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention (Vol. 14, No. 2: 459-466) (2005-03-06). Retrieved on 2008-03-05.

- ↑ Efthimiou E, Crnogorac-Jurcevic T, Lemoine NR, Brentnall TA (February 2001). "Inherited predisposition to pancreatic cancer". Gut 48 (2): 143–7. doi:. PMID 11156628.

- ↑ Michaud DS, Joshipura K, Giovannucci E, Fuchs CS (2007). "A prospective study of periodontal disease and pancreatic cancer in US male health professionals". J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 99 (2): 171–5. doi:. PMID 17228001.

- ↑ Bakkevold KE, Arnesjø B, Kambestad B (1992). "Carcinoma of the pancreas and papilla of Vater: presenting symptoms, signs, and diagnosis related to stage and tumour site. A prospective multicentre trial in 472 patients. Norwegian Pancreatic Cancer Trial". Scand. J. Gastroenterol. 27 (4): 317–25. doi:. PMID 1589710.

- ↑ Frank J. Domino M.D.etc. (2007). 5 minutes clinical suite version 3. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

- ↑ Pancreatic Cancer - Johns Hopkins Medicine: Surgical Treatment of Pancreatic Cancer

- ↑ Retrieved from http://pathology.jhu.edu/pancreas/TreatmentSurgery.php.

- ↑ Neoptolemos JP, Stocken DD, Friess H, et al (2004). "A randomized trial of chemoradiotherapy and chemotherapy after resection of pancreatic cancer". N. Engl. J. Med. 350 (12): 1200–10. doi:. PMID 15028824.

- ↑ Demols A, Peeters M, Polus M, et al (2006). "Gemcitabine and oxaliplatin (GEMOX) in gemcitabine refractory advanced pancreatic adenocarcinoma: a phase II study". Br. J. Cancer 94 (4): 481–5. doi:. PMID 16434988.

- ↑ FDA approval briefing

- ↑ Dhillon N, Aggarwal BB, Newman RA, et al (July 2008). "Phase II trial of curcumin in patients with advanced pancreatic cancer". Clin. Cancer Res. 14 (14): 4491–9. doi:. PMID 18628464.

- ↑ De Leon D. "Cancer News and Information: Curcumin Temporarily Slows Pancreatic Cancer". CancerWise.

- ↑ WHO | Cancer

- ↑ Jemal A, Siegel R, Ward E, Murray T, Xu J, Thun MJ (2007). "Cancer statistics, 2007". CA Cancer J Clin 57 (1): 43–66. PMID 17237035. http://caonline.amcancersoc.org/cgi/content/full/57/1/43.

- ↑ Wang F, Herrington M, Larsson J, Permert J (January 2003). "The relationship between diabetes and pancreatic cancer". Mol. Cancer 2: 4. doi:. PMID 12556242. PMC: 149418. http://www.molecular-cancer.com/content/2/1/4.

- ↑ "ACS :: Can Cancer of the Pancreas be Prevented?". Retrieved on 2007-12-13.

- ↑ Coughlin, SS; Calle EE, Patel AV, Thun MJ. (December 2000). "Predictors of pancreatic cancer mortality among a large cohort of United States adults". Cancer Causes Control. 11 (10): 915–23.. doi:. PMID 11142526.

- ↑ Zheng, W; et al (September 1993). "A cohort study of smoking, alcohol consumption, and dietary factors for pancreatic cancer (United States)". Cancer Causes Control. 4 (5): 477–82.. doi:. PMID 8218880.

- ↑ Larsson, Susanna; Niclas Håkansson, Ingmar Näslund, Leif Bergkvist and Alicja Wolk (February 2006). "Fruit and vegetable consumption in relation to pancreatic cancer risk: a prospective study". Cancer Epidemiology Biomarkers & Prevention 15: 301–305. doi:. PMID 16492919.

- ↑ BBC NEWS | Health | Vitamin D 'slashes cancer risk'

- ↑ Vitamin D May Cut Pancreatic Cancer

- ↑ http://www.forbes.com/forbeslife/health/feeds/hscout/2006/09/14/hscout534925.html

- ↑ Schernhammer E, Wolpin B, Rifai N, et al (June 2007). "Plasma folate, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, and homocysteine and pancreatic cancer risk in four large cohorts". Cancer Res. 67 (11): 5553–60. doi:. PMID 17545639. http://cancerres.aacrjournals.org/cgi/content/abstract/67/11/5553.

- ↑ "United Press International - Consumer Health Daily - Briefing". Retrieved on 2007-06-04.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 PanCAN - Working Together for a Cure™

External links

- The Johns Hopkins Pancreatic Cancer Web Site

- Pancreatic Cancer Action Network (PanCAN)

- The Pancreatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland

- The Johns Hopkins Pancreatic Cancer Web Site Discussion Board

- Rare Pancreatic & Neuroendocrine Cancer Support

- Pancreatic Cancer UK

- Confronting Pancreatic Cancer (Pancreatica.org)

- Cancer of the Pancreas (Cancer Supportive Care Program)

- American Cancer Society: Detailed Guide on Pancreatic Cancer

- The National Familial Pancreas Tumor Registry

- Pancreatic Cancer Collaborative Registry (PCCR)

- The Lustgarten Foundation For Pancreatic Cancer Research

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||