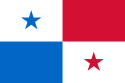

Panama

| Republic of Panama

República de Panamá (Spanish)

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "Pro Mundi Beneficio" (Latin) "For the Benefit of the World" |

||||||

| Anthem: Himno Istmeño (Spanish) |

||||||

|

||||||

| Capital (and largest city) |

Panama City |

|||||

| Official languages | Spanish | |||||

| Ethnic groups | 70% Mestizo, 14% Afro-west Indian, 10% white, 6% Amerindian[1] | |||||

| Demonym | Panamanian | |||||

| Government | Constitutional Democracy | |||||

| - | President | Martín Torrijos | ||||

| - | First Vice President | Samuel Lewis | ||||

| - | Second Vice President | Rubén Arosemena | ||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | from Spain | 28 November 1821 | ||||

| - | from Colombia | 3 November 1903 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 75,517 km2 (118th) 29,157 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | 2.9 | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | July 2008 estimate | 3,309,679 (133rd) | ||||

| - | May 2000 census | 2,839,177 | ||||

| - | Density | 43/km2 (156th) 111/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2007 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $34.605 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $10,351[2] | ||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2007 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $19.740 billion[2] | ||||

| - | Per capita | $5,904[2] | ||||

| Gini (2002) | 48.5 | |||||

| HDI (2007) | ▲ 0.812 (high) (62nd) | |||||

| Currency | Balboa, U.S. dollar ( PAB, USD) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC-5) | |||||

| - | Summer (DST) | (UTC-5) | ||||

| Drives on the | right | |||||

| Internet TLD | .pa | |||||

| Calling code | 507 | |||||

Panama, officially the Republic of Panama (Spanish: República de Panamá; Spanish pronunciation: [re̞ˈpuβ̞lika ð̞e̞ panaˈma]), is the southernmost country of Central America and, in turn, North America. Situated on an isthmus connecting North and South America, some categorize it as a transcontinental nation. It is bordered by Costa Rica to the north-west, Colombia to the south-east, the Caribbean Sea to the north and the Pacific Ocean to the south. It is an international business center and is also a transit country. Although Panama is the third largest economy in Central America, after Guatemala and Costa Rica, it is the largest consumer in Central America.[3]

Panama currently enjoys a rich Pre-Columbian heritage of native populations whose presence stretched back over 11,000 years. The earliest traces of these indigenous peoples include fluted projectile points. This changed into significant populations that are best known through the spectacular burials of the Conte site (dating to c. AD 500–900) and the polychrome pottery of the Coclé style. The monumental monolithic sculptures at the Barriles (Chiriqui) site were another important clue of the ancient isthmian cultures. Prior to the arrival of Europeans, Panama was widely settled by Chibchan, Chocoan, and Cueva peoples, among whom the largest group were the Cueva. There is no accurate knowledge of size of the indigenous population of the isthmus at the time of the European conquest. Estimates range as high as two million people, but more recent studies place that number closer to 200,000.

Contents |

History

Colonial Panama: discovery, conquest and decay

Christopher Columbus arrived in Panama on his fourth voyage in 1502, which started in Nicaragua and ended in Panama in 1503. It was on this trip that he discovered the Chagres river, which in the 20th Century would be the main resource to build the Panama Canal. He arrived at the Caribbean coast, where he baptized the area with the name of Portobelo (in English, Beautiful Port). Columbus then explored Veraguas and founded Santa Maria de Belen, which would be the first Spanish settlement on the continent, leaving Bartolome, his brother, in charge.

Founding of Panama La Vieja

It wasn't until 1519 when the Spanish decided to settle in the new city. This time they chose a site in the Pacific ocean, which was discovered six years before by Vasco Nuñez de Balboa. The new city, today known as Panama La Vieja, was founded in August 15th, 1519 by orders of governor Pedrarias Davila and became an important port during the Spanish gold trade from Peru to the Caribbean islands and finally to Europe. The merchandise from all over South America would come into Panama and travel to Portobelo using the Camino de Cruces (old stone road) crossing the jungle and navigating the Chagres river. From Portobelo it would distribute to the islands and then to Spain.

Because of its importance and its location the city was an easy target for pirates. However, protection from pirates was only one of its many problems, as it was settled in a site composed mainly by mangrove land, diseases and fires weakened their position, until it was finally destroyed by pirate Henry Morgan in 1671.

Founding of Casco Antiguo

In 1673 a new city of Panama was founded. This time, a rocky peninsula was chosen, still on the Pacific side. A healthier site with crossed winds and easier to defend from both land and ocean attacks. Called interchangeably Casco Viejo, San Felipe, Catedral or Casco Antiguo, it is from here where Panama would declare independence from Spain and later join and separate from Colombia. It will see the boom and bust of the Gold Rush, the French attempt to build a Canal and later its completion by the United States.

Independence

After approximately 320 years under the rule of the Spanish Empire, on November 3, 1821, independence from Spain was declared in the small town of La Villa, today known as La Heroica. On November 28, presided by Colonel Jose de Fabrega, a National Assembly was convened and it officially declared the independence of the isthmus of Panama from Spain and its decision to join New Granada, Ecuador and Venezuela in Bolivar's recently founded Republic of Colombia.

In 1830, Venezuela, Ecuador and other territories left the Gran Colombia, but Panama remained as a province of this country, until July 1831 when the isthmus reiterated its independence, now under General Juan Eligio Alzuru as supreme military commander. In August, military forces under the command of Colonel Tomás Herrera defeated and executed Alzuru and reestablished ties with New Granada.

Ten years later, on November 1840, during a civil war that had begun as a religious conflict, the isthmus declared its independence under the leadership of the now General Tomás Herrera and became the 'Estado Libre del Istmo', or the Free State of the Isthmus. The new state established external political and economic ties and drew up a constitution which included the possibility for Panama to rejoin New Granada, but only as a federal district. On June 1841 Tomás Herrera became the President of the Estado Libre del Istmo. But the civil conflict ended and the government of New Granada and the government of the Isthmus negotiated the reincorporation of Panamá to Colombia on December 31, 1841.

In the end, the union between Panama and the Republic of Colombia was made possible by the active participation of the US under the 1846 Bidlack Mallarino Treaty, which lasted until 1903. The treaty granted the US rights to build railroads through Panama and to intervene militarily against revolt to guarantee New Granadine control of Panama. There were at least three attempts by Panamanian Liberals to seize control of Panama and potentially achieve full autonomy, including one led by Liberal guerrillas like Belisario Porras and Victoriano Lorenzo, each of which was suppressed by a collaboration of Conservative Colombian and US forces under the Bidlack Mallarino Treaty.

In 1902 US President Theodore Roosevelt decided to take on the abandoned works of the Panama Canal by the French but the Colombian government in Bogotá balked at the prospect of a US controlled canal under the terms that Roosevelt's administration was offering. Roosevelt was unwilling to alter its terms and quickly changed tactics, encouraging a minority of Conservative Panamanian landholding families to demand independence, offering military support. On November 3, 1903 Panama finally separated and Dr. Manuel Amador Guerrero, a prominent member of the Conservative political party, became the first constitutional President of the Republic of Panama. The US, which had a small naval force in the area, prevented the Colombians from sending reinforcements by sea, aiding the Panamians.

In November 1903, Phillipe Bunau-Varilla—a French citizen who was not authorized to sign any treaties on behalf of Panama without the review of the Panamanians—unilaterally signed the Hay-Bunau Varilla Treaty which granted rights to the US to build and administer indefinitely the Panama Canal, which was opened in 1914. This treaty became a contentious diplomatic issue between the two countries, reaching a boiling point on Martyr's Day (9 January 1964). The issues were resolved with the signing of the Torrijos-Carter Treaties in 1977 returning the former Canal Zone territories to Panama.

Military dictators

The second intent of the founding fathers was to bring peace and harmony between the two major political parties. The Panamanian government went through periods of political instability and corruption, however, and at various times in its history, the mandate of an elected president terminated prematurely. In 1968, a coup toppled the government of the recently elected President Arnulfo Arias Madrid.

While never holding the position of President himself, General Omar Torrijos eventually became the de facto leader of Panama. As a military dictator, he was the leading power in the governing military junta and later became an autocratic strong man. Torrijos maintained his position of power until his death in an airplane accident in 1981.

After Torrijos's death, several military strong men followed him as Panama's leader. Commander Florencio Flores Aguilar followed Torrijos. Colonel Rubén Darío Paredes followed Flores. Eventually, by 1983, power was concentrated in the hands of General Manuel Antonio Noriega.

Manuel Noriega came up through the ranks after serving in the Chiriquí province and in the city of Puerto Armuelles for a time. He was a former head of Panama's secret police and was an ex-informant of the CIA. But Noriega's implication in drug trafficking by the United States resulted in difficult relations by the end of the 1980s.

United States invasion of Panama

On December 20 1989, 27,000 U.S. personnel invaded Panama in order to remove Manuel Noriega.[4] A few hours before the invasion, in a ceremony that took place inside a U.S. military base in the former Panama Canal Zone, Guillermo Endara was sworn in as the new President of Panama. The invasion occurred ten years before the Panama Canal administration was to be turned over to Panamanian authorities, according to the timetable set up by the Torrijos-Carter Treaties. During the fighting, between two hundred [5][6] and four thousand Panamanians,[7][8] mostly civilians, were killed. Estimates by the two major human rights organizations, Conlhuca and Conadehupa are 2,500 and 3,500 respectively. The Association of the Dead on December 20 estimates over 4,000 dead. To date, 15 mass graves have been found for which the U.S. military is directly responsible. [9]

Noriega surrendered to the American military shortly after, and was taken to Florida to be formally extradited and charged by U.S. federal authorities on drug and racketeering charges. He became eligible for parole on September 9, 2007, but remained in custody while his lawyers fought an extradition request from France. Critics have pointed out that many of Noriega's former allies remain in power in Panama.

Post-invasion

Under the Torrijos-Carter Treaties, the United States turned over all canal-related lands to Panama on 31 December 1999. Panama also gained control of canal-related buildings and infrastructure as well as full administration of the canal.

The people of Panama have already approved the widening of the canal which, after completion, will allow for post-Panamax vessels to travel through it, increasing the number of ships that currently use the canal.

Politics

Panama's politics takes place in a framework of a presidential representative democratic republic, whereby the President of Panama is both head of state and head of government, and of a multi-party system. Executive power is exercised by the government. Legislative power is vested in both the government and the National Assembly. The judiciary is independent of the executive and the legislature. All National elections are universal and mandatory to all citizens 18 years and older.

Provinces and regions

Panama is divided into nine provinces, with their respective local authorities (governors) and has a total of ten cities. Also, there are four Comarcas (literally: "Shires") which house a variety of indigenous groups.

Geography

Panama is located in Central America, bordering both the Caribbean Sea and the Pacific Ocean, between Colombia and Costa Rica. Its location on the Isthmus of Panama is strategic. By 2000, Panama controlled the Panama Canal that links the North Atlantic Ocean via the Caribbean Sea with the North Pacific Ocean.

The dominant feature of the country's landform is the central spine of mountains and hills that forms the continental divide. The divide does not form part of the great mountain chains of North America, and only near the Colombian border are there highlands related to the Andean system of South America. The spine that forms the divide is the highly eroded arch of an uplift from the sea bottom, in which peaks were formed by volcanic intrusions.

The mountain range of the divide is called the Cordillera de Talamanca near the Costa Rican border. Farther east it becomes the Serranía de Tabasará, and the portion of it closer to the lower saddle of the isthmus, where the canal is located, is often called the Sierra de Veraguas. As a whole, the range between Costa Rica and the canal is generally referred to by Panamanian geographers as the Cordillera Central.

The highest point in the country is the Volcán Barú (formerly known as the Volcán de Chiriquí), which rises to 3475 meters (11401 ft). A nearly impenetrable jungle forms the Darien Gap between Panama and Colombia. It creates a break in the Pan-American Highway, which otherwise forms a complete road from Alaska to Patagonia.

The National Bird

Classified as an endangered species, Harpy eagles are rare in captivity. These large birds are challenged in the wild because they require vast expanses of undisturbed forest. When they do breed, only one eaglet usually results. These large birds of prey generally eat monkeys and sloths in the wild. More common in the Darien area of Panama, there have been a few sightings near the border of Costa Rica.

Economy

According to the CIA World Factbook, Panama has an unemployment rate of 6.4% and according to the ECLAC,[10] the poverty rate is of 28.6% as of 2006, comparable to that of wealthier nations such as Argentina. Also, an alimentary surplus was registered in August 2008 and infrastructure works are progressing rapidly. The IMF has predicted that Panama will be the fastest growing economy in Latin American in 2009. [11] It was the second fastest growing economy in Latin America in 2008, after Peru.

Panama's economy is mainly service-based, heavily weighted toward banking, commerce, tourism, trading and private industries, due to its key geographic location. The handover of the canal and military installations by the United States has given rise to some construction projects. The Martín Torrijos administration has undertaken controversial structural reforms, such as a fiscal reform and a very difficult Social Security Reform. Furthermore, a referendum regarding the building of a third set of locks for the Panama Canal was approved overwhelmingly (though with low voter turnout) on 22 October 2006. The official estimate of the building of the third set of locks is US$5.25 billion.

The Panamanian currency is the balboa, fixed at parity with the United States dollar since 1903. In practice, however, the country is dollarized; Panama has its own coinage but uses US dollars for all its paper currency. Panama was the first of the three countries in Latin America to have dollarized their economies, later followed by Ecuador and El Salvador.

Globalization

The high levels of Panamanian trade are in large part from the Colón Free Trade Zone, the largest free trade zone in the Western Hemisphere. Last year the zone accounted for 92% of Panama's exports and 64% of its imports, according to an analysis of figures from the Colon zone management and estimates of Panama's trade by the United Nations Economic Commission for Latin America and the Caribbean (ECLAC). Panama's economy is also very much supported by the trade and exportation of coffee.

Inflation

According to the Economic Commission for Latin American and the Caribbean (ECLAC, or CEPAL by its more-commonly used Spanish acronym), Panama's inflation as measured by weight CPI was 2.0 percent in 2006.[12] Panama has traditionally experienced low inflation.

Real estate

Panama's strategic location, pension programs, tax exemptions, low cost of living, tropical and highland climates and investment incentives have seen and assisted with the ongoing real estate boom that has been affecting Panama City and the rest of the country.[13]

Apart from the existing demand, future developments may be helped by such factors as the planned expansion of the Panama Canal.

Bilateral Investment Treaty with the U.S.

The Bilateral Investment Treaty (BIT) between the governments of the United States and Panama was signed on October 27, 1982. The treaty protects U.S. investment and assists Panama in its efforts to develop its economy by creating conditions more favorable for U.S. private investment and thereby strengthening the development of its private sector. The BIT with Panama was the first such treaty signed by the U.S. in the Western Hemisphere.[14]

The importance of Panama to the U.S. stems from the Panama Canal which was built by the U.S. during the period of 1904–1914. Previously, if ships wanted to pass through the Americas, they would have to go all the way around the most southern tip of South America, the Tierra del Fuego, and through the Drake Passage. The Panama Canal connects the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans directly at the narrowest point in Panama. When previously a ship going from New York to San Francisco would have to travel for 20,900 kilometers (13,000 miles), now that travel time would be reduced to 8370 km (5200 mi).

The canal is of economic importance since it pumps millions of dollars from toll revenue to the national economy and provides massive employment. The United States had a complete monopoly over the Panama Canal for 85 years. However, the Torrijos-Carter Treaties signed in 1977 began the process of returning the canal to the Panamanian government in 1999 as long as they agreed to the neutrality of the canal, as well as allowing the U.S. to return at any time to defend this claim. This treaty, however, allows the national government to deny certain nations and companies the usage of the canal for certain reasons, such as national security.

Tourism

Along with real estate, tourism is one of Panama's rising economic activities. Small and amazingly diverse, Panama makes it possible for a traveler to visit not only two different oceans in one day, but be able to combine in less than a week a diversified natural experience (white sand beaches, cloud or rain forest, mountains or valleys) with a wide range of cultural experiences (seven Indian tribes, Afroantillian and Spanish Colonial culture, several historic monuments and a 300 year old World Heritage Site called Casco Antiguo (often referred as Casco Viejo, Panama Viejo, San Felipe or Catedral) [6]). In recent years the North Western and North Eastern regions of Panama have drawn increasing amounts of touristic activity because of their beaches, temperate and tropical rainforests, all within easy reach of popular Costa Rica. Bocas Del Toro, Boquete, and the surfing areas of the west coast are now huge tourist draws. Panama has become a cross roads for backpacking international tourists and has seen an increase in backpacker hostels. In the autonomous region of Kuna Yala and in the San Blas Islands (and even in the city of Panama), visitors can spot an interesting Native American group, the Kuna indigenous people. This group usually includes older women dressed in molas, colorful beads and decorative paintings on their faces. There is also a resort area called Farallón that brings visitors from all around the world. This resort contains three city-sized all-inclusive hotels and five apartment complexes as well as two golf courses, also, a large shopping complex is being built. Aerobic, scuba classes and tours to nearby Isla Farallón can be taken while visiting the resort.

Proposed Free Trade Agreement with the United States

A Trade Promotion Agreement between the United States and Panama was signed by both governments in 2007, but neither country has yet approved or implemented the Agreement.[15] While the U.S. Congress was initially favorably disposed to the Panama pact,[16] the election of the anti-American Pedro González, and his possible link with to the assassination of US soldier Zak Hernández, to the presidency of the Panamanian legislature on September 1, 2007 has halted progress of the pact in that body.

Demographics

According to the CIA World Factbook, Panama has a population of 3,309,679. The majority of the population, 70% is mestizo. The rest is 14% Amerindian and mixed West Indian, 10% white and 6% Amerindian.[1] The Amerindian population includes seven indigenous peoples, the Emberá, Wounaan, Guaymí, Buglé, Kuna, Naso and Bribri. More than half the population lives in the Panama City–Colón metropolitan corridor.

The culture, customs, and language of the Panamanians are predominantly Caribbean and Spanish. Spanish is the official and dominant language. About 40 percent of the population speak creole, mostly in Panama City and in the islands off the northeast coast.[17] English is spoken widely on the Caribbean coast and by many in business and professional fields.

Panama, because of its historical reliance on commerce, is above all a melting pot. This is shown, for instance, by its considerable population of Chinese origin. Many Chinese immigrated to Panama from southern China to help build the Panama Railroad in the 19th century; their descendants number around 50,000. Starting in the 1970s, a further 80,000 have immigrated from other parts of mainland China as well.[18][19]

The country is also the smallest in Spanish-speaking Latin America in terms of population (est. 3,232,000), with Uruguay as the second smallest (est. 3,463,000). However, since Panama has a higher birth rate, it is likely that in the coming years its population will surpass Uruguay's.

Religion

The overwhelming majority of Panamanians are Roman Catholic – various sources estimate that 75 to 85 percent of the population identifies itself as Roman Catholic and 15 to 25 percent as evangelical Christian.[20] The Bahá'í Faith community of Panama is estimated at 2.00% of the national population, or about 60,000[21] and is home to one of the seven Baha'i Houses of Worship.[20]

Smaller religious groups include Jewish and Muslim communities with approximately 10,000 members each, and small groups of Hindus, Buddhists and Rastafarians.[20] Indigenous religions include Ibeorgun (among Kuna) and Mamatata (among Ngobe).[20]

The Jewish community in Panama, with over 10,000 members, is by far the biggest in the region (including Central America and the Caribbean). Jewish immigration began in the late 19th century, and at present there are three synagogues in Panama City, as well as four Jewish schools. Within Latin America, Panama has one of the largest Jewish communities in proportion to its population, surpassed only by Uruguay, Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico. Panama is also the first country in Latin America to have a Jewish president, Eric Arturo Delvalle.

International rankings

| Index (Year) | Author / Editor / Source | Year of publication |

Countries sampled |

World Ranking (1) |

Ranking L.A.(2) |

| Environmental Performance (2008) | Yale University[22] |

|

149 | 32º |

|

| Democracy (2006) | The Economist[23] |

|

167 | 44º |

|

| Global Peace (2008) | The Economist[24] |

|

140 | 48º |

|

| Economic Freedom (2008) | The Wall Street Journal[25] |

|

157 | 46º |

|

| Quality-of-life (2005) | The Economist[26] |

|

111 | 47º |

|

| Travel and Tourism Competitiveness (2008) | World Economic Forum[27] |

|

130 | 50º |

|

| Press Freedom (2007) | Reporters Without Borders[28] |

|

169 | 54º |

|

| Global Competitiviness (2007) | World Economic Forum[29] |

|

131 | 59º |

|

| Human Development (2005) | United Nations (UNDP)[30] |

|

177 | 62º |

|

| Corruption Perception (2008) | Transparency International[31] |

|

180 | 85º |

|

| Income inequality (1989–2007)(3) | United Nations (UNDP)[32] |

|

126 | 115º |

|

| Life Satisfaction Index (2006-2007) (4) | Inter-American Development Bank[33] |

|

24 | N/A(4) |

|

- (1) Worldwide ranking among countries evaluated.

- (2) Ranking among the 20 Latin American countries (Puerto Rico is not included).

- (3) Because the Gini coefficient used for the ranking corresponds to different years depending of the country, and the underlying household surveys differ in method and in the type of data collected, the distribution data are not strictly comparable across countries. The ranking therefore is only a proxy for reference purposes, and though the source is the same, the sample is smaller than for the HDI

- (4) The Life Satisfaction Index study was performed by the Inter-American Development Bank among 24 countries in the Latin American and the Caribbean region, based on IDB calculations based on Gallup World Poll 2006 - 2007 and World Development Indicators. Therefore, it is a regional index.

See also

- List of Central America-related topics

- List of international rankings

- Lists of country-related topics

- Topic outline of geography

- Topic outline of North America

- Topic outline of South America

Notes and references

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "CIA - The World Factbook -- Panama". Retrieved on 2008-11-04.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 "Panama". International Monetary Fund. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ www.ilri.org/contentman/documentos/Sector%20Cárnico%20CA.pdf

- ↑ Lawrence A. Yates. "Operation JUST CAUSE in Panama City, December 1989". Combat Studies Institute. Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ [2]

- ↑ Craige, Betty Jean (1996). American Patriotism in a Global Society. SUNY Press. ISBN 0-7914-2959-8, p. 187

- ↑ "The Panama Deception" Part I

- ↑ Jose Morin, Center for the Constitutional Rights

- ↑ [3]

- ↑ [4]

- ↑ [5]PDF (95.9 KiB)

- ↑ Panama Real Estate News

- ↑ List of BITs currently in effect.

- ↑ U.S. Trade Representative's page on Panama TPA.

- ↑ News Release by Democratic Leadership of U.S. House of Representatives of July 2, 2007.

- ↑ Gordon, Raymond G., Jr. (ed.), (2005) .The main language is Spanish , as first and second language is speaked by a 98 per centLanguages of Panama. Ethnologue: Languages of the World, Fifteenth edition. Dallas, Tex.: SIL International. Online version. Retrieved on: April 6. 2008.

- ↑ Jackson, Eric (May 2004). "Panama's Chinese community celebrates a birthday, meets new challenges". The Panama News 10 (9). http://www.thepanamanews.com/pn/v_10/issue_09/community_01.html. Retrieved on 2007-11-07.

- ↑ "President Chen's State Visit to Panama". Government Information Office, Republic of China (October 2003). Retrieved on 2007-11-07.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 International Religious Freedom Report 2007: Panama. United States Bureau of Democracy, Human Rights and Labor (September 14, 2007). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ↑ "Panama". WCC > Member churches > Regions > Latin America > Panama. World Council of Churches (2006-01-01). Retrieved on 2008-07-01.

- ↑ Yale Center for Environmental Law & Policy / Center for International Earth Science Information Network at Columbia University. "Environmental Performance Index 2008, Metrics for Costa Rica". Retrieved on 2008-03-16.

- ↑ The Economist Intelligence Unit. "The World in 2007, Democracy Index 2006" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-03-13.

- ↑ The Economist Intelligence Unit et. al. (Vision of Humanity website). "Global Peace Index Rankings". Retrieved on 2008-05-28.

- ↑ The Heritage Foundation and The Wall Street Journal. "Index of Economic Freedom 2008". Retrieved on 2008-03-14.

- ↑ The Economist Intelligence Unit. "Pocket World in Figures 2008" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-03-13.

- ↑ World Economic Forum (2008). "The Travel & Tourism Competitiveness Report 2008" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-03-09.

- ↑ Reporters Without Borders. "Worldwide Press Freedom Index 2007". Retrieved on 2008-03-13.

- ↑ World Economic Forum. "The Global Competitiveness Report 2007-2008". Retrieved on 2008-03-09.

- ↑ UNPD Human Development Report 2007/2008. "Table 1: Human development index" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-03-11.

- ↑ Transparency International. "2008 Corruption Perception Index Ranking Table". Retrieved on 2008-09-28.

- ↑ UNPD Human Development Report 2007/2008. "Inequality in income or expenditure". Retrieved on 2008-03-14.

- ↑ Inter-American Development Bank. "Faster Economic Growth Hurts Life Satisfaction in Latin America and the Caribbean". Retrieved on 2008-11-23.

- Panama Canal Expansion Takes Major Step Forward, RESOURCE CANADA BUSINESS NEWS NETWORK, 25-JUL-2006

- Cómo localizar a los grupos del ‘sí’ y ‘no’, 11 de agosto de 2006

Further reading

- Murillo, Luis E. (1995). The Noriega Mess: The Drugs, the Canal, and Why America Invaded. 1096 pages, illustrated. Berkeley: Video Books. ISBN 0-923444-02-5.

- Mellander, Gustavo A. (1971) The United States in Panamanian Politics: The Intriguing Formative Years. Danville, Ill.: Interstate Publishers, OCLC 138568

- Mellander, Gustavo A.; Nelly Maldonado Mellander (1999). Charles Edward Magoon: The Panama Years. Río Piedras, Puerto Rico: Editorial Plaza Mayor. ISBN 1563281554. OCLC 42970390.

External links

- Government and Diplomacy

- (Spanish) The President of Panama

- (Spanish) List of Panamanian Government Agencies

- (Spanish) Ministry of External Relations

- Embassy of Panama in the U.S.

- National Directorate of Immigration and Naturalization

- Tourism and Travel

- Official Site of the Panama Canal Authority

- Official Site of the Panama Tourism Bureau

- Photos Of Panama

- General

- Panama entry at The World Factbook

- Panama at UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Panama at the Open Directory Project

- Economy and Business

- (Spanish) Ministry of Economics and Finance

- (Spanish) Bolsa de Valores (Panama Stock Exchange)

- (Spanish) Comisión Nacional de Valores (Panama SEC)

- American Chamber of Commerce & Industry of Panama

- List of all Panama Banks

- Retiring in Panama, retirement investments in real estate

- Nature conservation

- [7] reforestation for the endemic Squirrel Monkey

- Media and Discussion

- (Spanish) La Prensa

- (Spanish) Mi Diario

|

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||