Oxycodone

|

|

|

Oxycodone

|

|

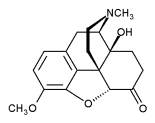

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

| 4, 5-epoxy-14-hydroxy-3- methoxy-17-methylmorphinan-6-one | |

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| ATC code | N02 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C18H21NO4 |

| Mol. mass | 315.364 g/mol |

| SMILES | & |

| Synonyms | Dihydrohydroxycodeinone, 14-Hydroxydihydrocodeinone |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | Up to 87% |

| Protein binding | 45% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic (CYP450: 2D6 substrate) |

| Half life | 3 - 4.5 hours |

| Excretion | Urine (19% unchanged) |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. |

B/D (prolonged use or in high doses at term) |

| Legal status |

Controlled (S8)(AU) Schedule I(CA) Class A(UK) Schedule II(US) |

| Dependence Liability | Moderate - High |

| Routes | Oral, intramuscular, intravenous, intranasally, subcutaneous, transdermal, rectal |

Oxycodone is an opioid analgesic medication synthesized from thebaine. It was developed in 1916 in Germany, as one of several new semi-synthetic opioids with several benefits over the older traditional opiates and opioids; morphine, diacetylmorphine (heroin) and codeine. It was introduced to the pharmaceutical market as Eukodal or Eucodal and Dinarkon. Its chemical name is derived from codeine - the chemical structures are very similar, differing only in that the hydroxyl group of codeine has been oxidized to a carbonyl group (as in ketones), hence the "-one" suffix, the 7,8-dihydro-feature (codeine has a double-bond between those two carbons), and the hydroxyl group at carbon-14 (codeine has just a hydrogen in its place), hence oxycodone.

Contents |

History

Oxycodone was first synthesized in a German laboratory in 1916, a few years after the German pharmaceutical company Bayer had stopped the mass production of heroin due to addiction and abuse. It was hoped that a thebaine-derived drug would retain the analgesic effects of morphine and heroin with less addiction. To some extent this was achieved, as oxycodone does not have the same immediate effect as heroin or morphine nor does it last as long.

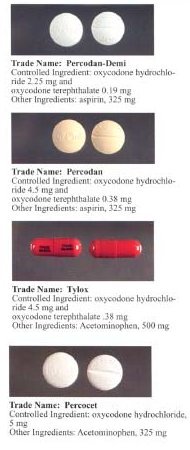

It was first introduced to the US market in May 1939 and is the active ingredient in a number of pain medications commonly prescribed for the relief of moderate to severe pain, either with inert binders, e.g. (oxycodone, OxyContin) or supplemental analgesics such as paracetamol (acetaminophen), e.g. (Percocet, Endocet, Tylox, Roxicet) or aspirin (Percodan, Endodan, Roxiprin ). More recently, ibuprofen has been added to oxycodone under the name (Combunox).

Clinical use

In palliative care, oxycodone is viewed as a second line opioid to morphine, along with other second-line strong opioids such as hydromorphone and fentanyl.[1] There is no evidence that any opioids are superior to morphine in relieving the pain of cancer, and no controlled trials have shown oxycodone to be superior to morphine.[2] However, switching to an alternative opioid can be useful if adverse effects are troublesome, although the switch can be in either direction, i.e. some patients have fewer adverse effects on switching from morphine to oxycodone and vice versa.

Oxycodone has the disadvantage of accumulating in patients with renal and hepatic impairment. In addition, and unlike morphine and hydromorphone, it is metabolized by the cytochrome P450 enzyme system in the liver, making it vulnerable to drug interactions.[3] It is metabolized to the very active opioid analgesic oxymorphone.[4] Some people are fast metabolizers resulting in reduced analgesic effect but increased adverse effects, while others are slow metabolisers resulting in increased toxicity without improved analgesia.[5][6]

Manufacture and patents

An extended-release formulation of oxycodone, OxyContin, was first introduced to the US market by Purdue in 1996. Purdue has multiple patents for OxyContin, but has been involved in a series of ongoing legal battles on the validity of these patents. On June 7, 2005, the United States Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit, upheld a decision from the previous year that some of Purdue’s patents for OxyContin could not be enforced.[7] This decision allowed and led to the immediate announcement from Endo Pharmaceuticals that they would begin launching a generic version of all four strengths of OxyContin.[8] Purdue, however, had already made negotiations with another pharmaceutical company (IVAX Pharmaceuticals) to distribute their brand OxyContin in a generic form. This contract was severed, and currently Watson Pharmaceuticals is the exclusive U.S. distributor of Purdue-manufactured generic versions of OxyContin tablets in 10, 20, 30, 40, 60, and 80 milligram dosages in the United States.[9]

On February 1, 2006, the Federal Circuit Court of Appeals issued a revised decision varied their prior decision.[10] The court concluded that the patents-in-suit are unenforceable, and the case is remanded for further proceedings. Purdue Pharma has since announced resolution of its infringement suits with Endo,[11] Teva,[12] IMPAX,[13] and Mallinckrodt.[14] Endo and Teva each agreed to cease selling generic forms of OxyContin, while IMPAX negotiated a temporary, and potentially renewable, license, and Mallinckrodt negotiated a temporary license ending in 2009.

In 2001, OxyContin was the highest sold drug of its kind, and in 2000, over 6.5 million prescriptions were written.[15]

OxyContin misbranding and fraud

Critics have accused Purdue of putting profits ahead of public interest by understating or ignoring the addictive potential of the drug.[16][17][18]

Purdue Pharma and its top executives pleaded guilty to felony charges that they misbranded and misled physicians and the public by claiming OxyContin was less likely to be abused, less addictive, and less likely to cause withdrawal symptoms than other opiate drugs.[19] The company also paid millions in fines relating to aggressive off-label marketing practices in several states.[20]

Abuse

Oxycodone is a drug subject to abuse.[21][22] The drug is included in the sections for the most strongly controlled substances that have a commonly accepted medical use, including the German Betäubungsmittelgesetz III (narcotics law), the Swiss law of the same title, UK Misuse of Drugs Act (Class A), Canadian Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA), Dutch Opium Law (List 1), Austrian Suchtmittelgesetz (Addictives Act), and others. It is also subject to international treaties controlling psychoactive drugs subject to abuse or dependence.

The introduction of higher strength preparations in 1995 resulted in increasing patterns of abuse.[21] Unlike Percocet, whose potential for abuse is somewhat limited by the presence of paracetamol (acetaminophen), OxyContin and other extended release preparations contain mainly oxycodone. Abusers crush the tablets to break the time-release coating and then ingest the resulting powder orally, intra-nasally, rectally, or by injection. Research has shown that the brains of adolescent mice, which were exposed to OxyContin, can sustain lifelong and permanent changes in their reward system.[23][24] It is notable that the vast majority of OxyContin related deaths are attributed to ingesting substantial quantities of oxycodone in combination with another depressant of the central nervous system such as alcohol, barbiturates and related drugs.[25]

Illegal distribution of OxyContin occurs through pharmacy diversion, physicians, doctor shopping, faked prescriptions, and robbery. In Australia during 1999 and 2000, more than 260,000 prescriptions for narcotics and codeine-based medications were written to almost 9,000 known abusers at a cost of more than $750,000 AUD (approx $602,000 US).[22]

Regulation

Regulation of oxycodone (and opioids in general) differs according to country, with different places focusing on different parts of the supply chain.

Australia

A General Practitioner can prescribe for short term treatment without consulting another practitioner or government body. Only twenty tablets are normally available per prescription on the Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme, Australia's government-funded pharmaceutical insurance system, but with prior approval from Medicare Australia a patient can potentially get up to sixty tablets. Prescriptions for chronic pain or cancer patients require the prescriber to have referred the patient to another medical practitioner to confirm the need for ongoing treatment with narcotic analgesics. Pharmacists must record all incoming purchases of oxycodone products, and maintain a register of all prescription sales for inspection by their state Health Department on request. In addition details of all Pharmaceutical Benefits Scheme prescriptions for oxycodone are sent to Medicare Australia. This data allows Medicare Australia to assist prescribers to identify doctor-shoppers via a telephone hotline.

Canada

Oxycodone is a controlled substance under Schedule I of the Controlled Drugs and Substances Act (CDSA). Every person who seeks or obtains the substance without disclosing authorization to obtain such substances 30 days prior to obtaining another prescription from a practitioner is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for a term not exceeding seven years. Possession for purpose of trafficking is guilty of an indictable offence and liable to imprisonment for life.

Germany

Only physicians (Ärzte) can prescribe oxycodone. Prescribing physicians need to have a special BtM number (controlled substance number). BtM prescriptions are handled very cautiously and the central Federal Opium Bureau (Bundesopiumstelle) records all traffic.

Hong Kong

Oxycodone is regulated under Schedule 1 of Hong Kong's Chapter 134 Dangerous Drugs Ordinance. It can only be used legally by health professionals and for university research purposes. The substance can be given by pharmacists under a prescription. Anyone who supplies the substance without a prescription can be fined $10,000 (HKD). The penalty for trafficking or manufacturing the substance is a $5,000,000 HKD fine and/or life imprisonment. Possession of the substance for consumption without license from the Department of Health is illegal with a $1,000,000 HKD fine and/or 7 years of jail time.

United Kingdom

Oxycode is a Class A schedule 2 drug under the Misuse of Drugs Act. [26] It is available by prescription from a GP on the NHS for short-term severe pain and long-term for cancer patients. Possession without a prescription is punishable by up to seven years in prison, an unlimited fine, or both. Dealing of the drug illegally is punishable by up to life imprisonment, an unlimited fine, or both.[27]

United States

Oxycodone is a schedule II controlled substance, i.e. it must be given by written prescription which cannot have refills, nor can it be called in to a pharmacy by a physician. Trafficking (dealing) is punishable at first offense by not more than 20 years imprisonment. If there's a related death or serious injury, then not less than 20 years (up to life sentence) and a fine of US$1 million if an individual or US$5 million if not an individual. On second offense the penalty is of not more than 30 years imprisonment. If there's a death or serious injury, not less than a life sentence and a fine of US$2 million if an individual or US$10 million if not an individual. [28]

Dosage and administration

Oxycodone can be administered orally, intranasally, via intravenous/intramuscular/subcutaneous injection or rectally. The bioavailability of oral administration averages 60-87%, with rectal administration yielding the same results. Oxycodone is approximately 1.5× - 2x as potent as morphine when administered orally.[29],[30] However, 10-15mg of oxycodone produces an analgesic affect similar to 10mg of morphine when administered intramuscularly. Therefore as a parenteral dose morphine is approximately up to 50% more potent than oxycodone. [31] There are no comparative trials showing that oxycodone is more effective than any other opioid. In palliative care, morphine remains the gold standard.[2] However, it can be useful as an alternative opioid if a patient has troublesome adverse effects with morphine.

Percocet tablets (oxycodone with paracetamol/acetaminophen), are routinely prescribed for post-operative pain control. Tablets are available with 2.5, 5, 7.5, 10, or 15 mg of oxycodone and varying amounts of acetaminophen. Oxycodone is also used in treatment of moderate to severe chronic pain.

OxyNorm is available in 5, 10, and 20 mg capsules and tablets, and also as a 1 mg/1 ml liquid in 250 ml bottles and as a 10 mg/1 ml concentrated liquid in 100 ml bottles. Available in Europe and other areas outside the United States, Proladone suppositories contain 15 mg of oxycodone pectinate and other suppository strengths under this and other trade names are less frequently encountered. Injectable oxycodone hydrochloride or tartrate is available in ampoules and multi-dose vials in many European countries and to a lesser extent various places in the Pacific Rim. For this purpose, the most common trade names are Eukodol and Eucodol.

Roxicodone is a generically made oxycodone product designed to have an immediate release effect for rapid pain relief, and is available in 5 (white), 15 (green), and 30 (light blue) mg tablets. Generic versions of Roxicodone may differ in color from the brand name tablets.

OxyContin

Available in, 10 mg (white), 15 mg (black), 20 mg (pink), 30 mg (brown), 40 mg (orange), 60 mg (red), and 80 mg (green) in the U.S. and Canada; 160 mg (blue) in Canada only, and 5 mg (blue) in Europe. Because of its sustained-release mechanism, the medication is typically effective for eight to twelve hours.[3] The 160 mg tablets were removed from sale due to problems with overdose, but have been re-introduced for limited use under strict medical supervision.

Generic OxyContin was introduced in 2005 (80 mg) and 2006 (10, 20, and 40 mg). However, because of numerous law suits noted above, generic manufacture ceased on December 31, 2007. Oxycodone/APAP pills are still available through prescription only

Side effects

The most commonly reported effects include constipation, fatigue, dizziness, nausea, lightheadedness, headache, dry mouth, anxiety, pruritus, euphoria, and diaphoresis.[32] It has also been claimed to cause dimness in vision due to miosis. Some patients have also experienced loss of appetite, nervousness, abdominal pain, diarrhea, dyspnea, and hiccups,[3] although these symptoms appear in less than 5% of patients taking oxycodone. Rarely, the drug can cause impotence, enlarged prostate gland, and decreased testosterone secretion.[33]

In high doses, overdoses, or in patients not tolerant to opiates, oxycodone can cause shallow breathing, bradycardia, cold, clammy skin, apnea, hypotension, pupil constriction, circulatory collapse, respiratory arrest, and death.[3]

There is a high risk of experiencing severe withdrawal symptoms if a patient discontinues oxycodone abruptly. Therefore therapy should be gradually discontinued rather than abruptly discontinued. Drug abusers are at even higher risk of severe withdrawal symptoms as they tend to use higher than prescribed doses. Withdrawal symptoms are also likely in neonates born to mothers who have been taking oxycodone or other opiate based pain killers during their pregnancy. The symptoms of oxycodone withdrawal are the same as for other opiate based pain killers and may include the following symptoms.[34][35]

- Anxiety

- Nausea

- Insomnia

- Muscle pain

- Fevers

- Flu like symptoms

- Severe Restlessness

References

- ↑ www.palliativedrugs.com

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Calman K. Doyle D, Hanks G, Editors, ed. (1999). Oxford Textbook of Palliative Medicine. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0192625667.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 3.3 Rappaport, Bob (2006-09-18). "Package Insert: OxyContin" (PDF). Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Kalso, E. (May 2005). "Oxycodone". Journal of Pain & Symptom Management 29 (5): 47–56. doi:.

- ↑ Gasche Y, Daali Y, Fathi M, et al (December 2004). "Codeine intoxication associated with ultrarapid CYP2D6 metabolism". N. Engl. J. Med. 351 (27): 2827–31. doi:. PMID 15625333. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/pmidlookup?view=short&pmid=15625333&promo=ONFLNS19.

- ↑ Otton SV, Wu D, Joffe RT, Cheung SW, Sellers EM (April 1993). "Inhibition by fluoxetine of cytochrome P450 2D6 activity". Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 53 (4): 401–9. PMID 8477556.

- ↑ Purdue Pharma L.P. v. Endo Pharms. Inc, 410 F.3d 690 (Fed.Cir. 2005-06-07).

- ↑ Purdue Pharma (2005-06-08). "Purdue Comments on Federal Court of Appeal Decision on OxyContin Patent Litigation". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Purdue Pharma (2005-10-28). "Purdue Appoints Watson Pharmaceuticals Exclusive Distributor of Authorized Generic Versions of OxyContin Tablets". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Purdue Pharma L.P. v. Endo Pharms. Inc., 438 F.3d 1123 (Fed.Cir. 2006-02-01).

- ↑ Purdue Pharma (2006-08-28). "Purdue Pharma L.P. Announces Resolution of OxyContin® Patent Lawsuit with Endo Pharmaceuticals". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Purdue Pharma (2006-10-16). "Purdue Pharma L.P. Announces Signing of Consent Judgment Ending OxyContin® Tablets Patent Lawsuit with Teva Pharmaceuticals". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Purdue Pharma (2007-04-02). "Purdue Pharma L.P. Announces Agreement to End OxyContin® Patent Lawsuit with IMPAX Laboratories". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Purdue Pharma (2008-09-02). "Purdue Pharma L.P. Announces Resolution of OxyContin® Patent Lawsuit with Mallinckrodt Inc.". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-09-17.

- ↑ "OxyContin". drugpolicy.org. Drug Policy Alliance. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Bauerlein, Valerie (2001-09-23). "Popular Painkiller Mired in Controversy" (reprint), The State. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Rosenberg, Debra (2001-07-02). "Drugs: Profits vs. Pain Relief" (reprint), Newsweek. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ "Editorial: Selling Drugs Legally, But Not Always Safely" (reprint), Roanoke Times (2001-06-13). Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ O'Brien, John (2007-05-10). "Purdue pleads out, will pay $634 million in fines". LegalNewsline.com. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Staff writer (2007-05-09). "Drugmaker to pay $19.5 mil to settle OxyContin lawsuit", Arizona Republic, Associated Press. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Cicero TJ, Inciardi JA, Muñoz A (October 2005). "Trends in abuse of Oxycontin and other opioid analgesics in the United States: 2002-2004". J Pain 6 (10): 662–72. doi:. PMID 16202959. http://linkinghub.elsevier.com/retrieve/pii/S1526-5900(05)00656-5.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 Seidler, Raymond (July 2002). "Prescription Drug Abuse" (PDF). Current Therapeutics. http://www.nswrdn.com.au/client_images/6700.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ Kreek MJ, Schlussman SD, Reed B, Zhang Y, Nielsen DA, Levran O, Zhou Y, Butelman ER (August 7 2008). "Bidirectional translational research: Progress in understanding addictive diseases.". Neuropharmacology.. doi:. PMID 18725235.

- ↑ Painkiller Abuse Can Predispose Adolescents to Lifelong Addiction Newswise, Retrieved on September 10, 2008.

- ↑ "Summary of Medical Examiner Reports on Oxycodone-Related Deaths". DEA Office of Diversion Control. United States Department of Justice. Retrieved on 2008-05-18.

- ↑ "Misuse of drugs list of drugs by group" (in English). Home Office (August 2008). Retrieved on 2008-11-29.

- ↑ "Class A, B and C drugs" (in English). Home Office (January 2007). Retrieved on 2008-11-29.

- ↑ "DEA Federal Trafficking Penalties" (in English). US Drug Enforcement Agency. Retrieved on 2008-11-29.

- ↑ http://www.pharma.com/PI/Prescription/Oxycontin.pdf

- ↑ Palliative Care Perspectives. James L. Hallenbeck

- ↑ http://pharmaceuticals.mallinckrodt.com/_attachments/PackageInserts/57_Oxy%20HCl%20Tabs_REV081007.pdf

- ↑ Oxycodone Side Effects

- ↑ "Oxycodone Addiction". addictionsearch.com (2007-02-08).

- ↑ Rao, R; Desai, Ns (June 2002). "OxyContin and neonatal abstinence syndrome" (Free full text). Journal of perinatology : official journal of the California Perinatal Association 22 (4): 324–5. doi:. PMID 12032797.

- ↑ "Oxycodone". Center for Substance Abuse Research (May 2, 2005). Retrieved on September 10, 2008.

External links

- Images of various preparations of Oxycodone and Oxycodone controlled release

- Oxycodone: Pharmacological profile and clinical data in chronic pain management minervamedica.it. Minerva Anestesiologica, 2005;71:451-60.

- Percocet Drug Information from Thomson Healthcare database

- Oxycontin makers and executives plead guilty to coverup of dangers and addictive qualities

- "When Is a Pain Doctor a Drug Pusher?' New York Times 6-17-2007

- 'Deadly Combinations' St. Petersburg Times 2-17-08

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||