Oud

|

|

| Classification | *Necked bowl lutes |

|---|---|

| Related instruments | *Angélique (instrument)

|

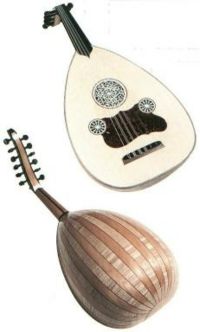

The oud (Arabic: عود ʿūd, plural: أعواد, a‘wād; Somali: kaban; Persian: بربط barbat; Turkish: ud or ut;[1] Greek: ούτι; Armenian: ուդ, Azeri: ud; Hebrew: עוד ud) is a pear-shaped, stringed instrument, which is often seen as the predecessor of the western lute, distinguished primarily by being without frets, commonly used in Middle Eastern music.

Contents |

Name

The words "lute" and "oud" are both speculated to be derived from Arabic العود (al-ʿūd), consisting of the Arabic letters ʿayn-wāw-dāl, meaning a thin piece of wood similar to the shape of a straw, referring either to the wood plectrum used traditionally for playing the lute[1], or to the thin strips of wood used for the back, or for the fact that the top was made of wood, not skin as were earlier. However, recent research by Eckhard Neubauer[2] suggests that ʿūd may simply be an Arabized version of the Persian name rud, which meant string, stringed instrument, or lute. Gianfranco Lotti suggests that the "wood" appellation originally carried derogatory connotations, because of proscriptions of all instruments of music in early Islam.

The Oud is also popular in Azerbaijan where it is known as an Ud. The Ud found its way into Azerbaijani culture during the 7th century. Most Azerbaijani mughams are played on the Ud by Ahsan Dadashov.

The Arabic prefix al-, in al-ʿūd, which represents the definite article and can be translated as "the," was not retained when al-ʿūd, was borrowed into Turkish, nor was the ʿayn, as it is not a sound existing in the Turkish language. The resulting word in Turkish is simply ud (pronunciation follows that of the word good without the g ).

The oud was most likely introduced to Western Europe by the Arabs who established the Umayyad Caliphate of Al-Andalus on the Iberian Peninsula beginning in the year 711 AD. Oud-like instruments such as the Ancient Greek Pandoura and the Roman Pandura likely made their way to the Iberian Peninsula much earlier than the oud. However, it was the royal houses of Al-Andalus that cultivated the environment which raised the level of oud playing to greater heights and boosted the popularity of the instrument. The most famous oud player of Al-Andalus was Zyriab. He established the first music conservatory in Spain, enhanced playing technique and added a fifth course to the instrument. The European version of this instrument came to be known as the lute - luth in French, laute in German, liuto in Italian, luit in Dutch, (all beginning with the letter "L") and alaud in Spanish. The word "luthier" meaning stringed instrument maker is also derived from the French luth. Unlike the oud the European lute utilized frets (usually tied gut).

History

According to Farabi, the oud was invented by Lamech, the sixth grandson of Adam. The legend tells that the grieving Lamech hung the body of his dead son from a tree. The first oud was inspired by the shape of his son's bleached skeleton.[2] The oldest pictorial record of a lute dates back to the Uruk period in Southern Mesopotamia - Iraq - Nasria city nowadays, over 5000 years ago on a cylinder seal acquired by Dr. Dominique Collon and currently housed at the British Museum. The image depicts a female crouching with her instruments upon a boat, playing right-handed. This instrument appears many times throughout Mesopotamian history and again in ancient Egypt from the 18th dynasty onwards in long and short-neck varieties. One may see such examples at the Metropolitan Museums of New York, Philadelphia, Cleveland, and the British Museum on clay tablets and papyrus paper. This instrument and its close relatives have been a part of the music of each of the ancient civilizations that have existed in the Mediterranean and the Middle East regions, including the Sumerians, Akkadians, Persians, Babylonians, Assyrians, Armenians, Greeks, Egyptians, and Romans.

The ancient Turkic peoples had a similar instrument called the kopuz. This instrument was thought to have magical powers and was brought to wars and used in military bands. This is noted in the Göktürk monument inscriptions, the military band was later used by other Turkic state's armies and later by Europeans.[3] According to Musicolog Çinuçen Tanrıkorur today's oud was derived from the kopuz by Turks near Central Asia and additional strings were added by them.[4] Today's oud is totally different from the old prototypes and the Turkish oud is different from Arabic oud in playing style and shape. The Turkish is derived from modifying the Arabic oud, whose development has been attributed to Manolis Venios, a well known Greek luthier who lived Constantinople (Istanbul) in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. In Greece and Armenia musicians especially use the Turkish ouds and tunings.

The oud has a particularly long tradition in Iraq,[5] where a saying goes that in its music lies the country’s soul.[5] A ninth-century Baghdad jurist praised the healing powers of the instrument, and the 19th century writer Muhammad Shihab al-Din related that it "places the temperament in equilibrium" and "calms and revives hearts."[5] Following the invasion of Iraq and the overthrow of the secular Hussein regime in 2003, however, the increasing fervor of Islamic militants who consider secular music to be haraam (forbidden) forced many Oud players or teachers into hiding or exile.[5]

Defining features

- Lack of Frets: The oud, unlike many other plucked stringed instruments, does not have a fretted neck. This allows the player to be more expressive by using slides and vibrato. It also makes it possible to play the microtones of the Maqam System. This development is relatively recent, as ouds still had frets ca. AD 1100, and they gradually lost them by AD 1300, mirroring the general development of Near-Eastern music which abandoned harmony in favor of melismatics.

- Strings: With some exceptions, the modern oud has eleven strings. Ten of these strings are paired together in courses of two. The eleventh, lowest string remains single. There are many different tuning systems for the oud which are outlined below. The ancient oud had only four courses - five by the 9th century. The strings are generally lighter to play than the modern classical guitar.

- Pegbox: The pegbox of the oud is bent back at a 45-90° angle from the neck of the instrument. This provides the necessary tension that prevents the pegs from slipping.

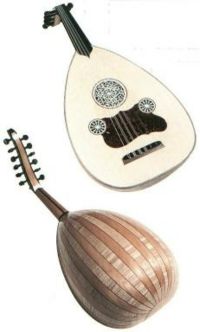

- Body: The oud's body has a staved, bowl-like back resembling the outside of half a watermelon, unlike the flat back of a guitar. This bowl allows the oud to resonate and have a more complex tone.

- Sound-holes: The oud generally has one to three sound-holes, which may be either oval or circular, and often are decorated with a bone or wood carved rosette.

Construction

Construction of the oud is similar to that of the lute.[6] The back of the instrument is made of thin wood staves glued together on edge. Alternating staves of light and dark wood are often used. The instrument usually has an odd number of staves. This means the back will have a center stave rather than a center seam. Contrasting trim pieces are often used between staves. Patterns and wood species used generally vary from maker to maker.

The top of the oud is generally made of two matching pieces of thin spruce glued together on edge. Transverse braces, also of spruce, are glued to the underside of the top.

The neck is generally made of a single piece of wood and is usually veneered in a striped pattern similar to that of the back. The pegbox meets the neck at a severe angle. The pegbox is usually made from separate side, end and back pieces glued together.

Regional types

The following are the general regional characteristics of oud types in which both the shape and the tuning most commonly differ:

- Arabic ouds:

-

- Syrian ouds: Slightly larger, slightly longer neck, lower in pitch.

- Iraqi (Munir Bashir type) ouds: Generally similar in size to the Syrian oud but with a floating bridge which focuses the mid-range frequencies and gives the instrument a more guitar-like sound. This kind of oud was developed by the Iraqi oud virtuoso Munir Bechir. Iraqi ouds made today often feature 13 strings, adding a pair of higher pitched nylon strings to a standard Arabic oud configuration.

- Egyptian ouds: Similar to Syrian and Iraqi ouds but with a more pear shaped body. Slightly different tone. Egyptians commonly are set up with only the 5 courses GADGC. Egyptian Ouds tend to be very ornate and highly decorated.

- Turkish| Greek style ouds ("ud,ούτι") (Includes instruments found in Armenia and Greece): Slightly smaller in size, slightly shorter neck, higher in pitch, brighter timbre. It's known as outi in Greece and was used by early Greek musicians.

- Barbat (Persian Oud): smaller than Arabic ouds with different tuning and higher tone. Similar to Turkish ouds but slightly smaller.

- Oud Qadim: an archaic type of oud from North Africa, now out of use.

Although the Greek instruments Laouto and Lavta appear to look much like an oud, they are very different in playing style and origin, deriving from Byzantine lutes. The laouto is mainly a chordal instrument, with occasional melodic use in Cretan music. Both always feature movable frets (unlike the oud).

Plectrum (pick)

The plectrum (pick) for the oud is usually a little more than the length of an index-finger. The Arabs traditionally used thin piece of wood as a plectrum, later replaced by the eagle's feather by Zyriab in Spain (between 822 to 857), other sources state that he is the first one to use the wooden plectrum[3].

To date the Arabic players use the historic name reeshe or risha(Arabic ريشة), which literally means "feather" while Turkish players refer to it as a mızrap.. Currently the plastic pick is most commonly used for playing the oud being effective, affordable and convenient to get.

Like similar strummed stringed instruments, professional Oud players take the quality of their plectrums very seriously, often making their own out of other plastic objects, and taking great care to sand down any sharp edges in order to achieve the best sound possible.

Oud tunings

There are many different tuning options for the oud. All tunings are presented from the lowest course/single string to the highest course. The following tunings are from Lark in the Morning and Oud Cafe: Oud

Arabic oud tunings

- C F A D G C Currently the most commonly used tuning.

- D G A D G C Older tuning

- E A D G C Five Strings (Syria, Palestine and Lebanon) - by Eduardo Haddad Ribeiro

- G A D G C Popular Egyptian tuning

- B E A D G C For certain classical music, similar to the classical Turkish tuning in all 4ths

- B E A D G C F Seven strings oud tuning.

- F A D G C F high pitched solo tuning

- G C D G C F

Turkish oud ("ud") and Cümbüş tunings

- Old Turkish, Armenian and Greek Tuning: E A B E A D or D A B E A D

- Classical Turkish and Tuning Variant: C# F# B E A D or B F# B E A D

Note - Turkish classical music is written transposed, so that the written tuning for the above tuning is "F#BEADG"; also the Turks will transpose to other keys, too.

- Standard Cümbüş Tuning: ABEADG actual pitch, written as D E A D G C

List of famous oud players

|

In Canada

In Greece:

In Egypt:

In Iran:

In Iraq:

In Israel:

In Kuwait:

In Lebanon:

|

In Morocco:

In Palestine:

In Saudi Arabia:

In Somalia:

In Sudan:

In Syria:

In Tunisia:

In Turkey:

|

In Yemen:

Others:

|

References

- ↑ Güncel Türkçe Sözlük'te Söz Arama (Turkish)

- ↑ Erica Goode (May 1, 2008). "A Fabled Instrument, Suppressed in Iraq, Thrives in Exile", New York Times. (citing Grove Music Online)

- ↑ Fuad Köprülü, Türk Edebiyatında İlk Mutasavvıflar (First Sufis in Turkish Literature), Ankara University Press, Ankara 1966, pp. 207, 209.; Gazimihal; Mahmud Ragıb, Ülkelerde Kopuz ve Tezeneli Sazlarımız, Ankara University Press, Ankara 1975, p. 64.; Musiki Sözlüğü (Dictionary of Music), M.E.B. İstanbul 1961, pp. 138, 259, 260.; Curt Sachs, The History of Musical Instruments, New York 1940, p. 252.

- ↑ http://www.aksiyon.com.tr/detay.php?id=15164 (Turkish)

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 5.2 5.3 Erica Goode (May 1, 2008). "A Fabled Instrument, Suppressed in Iraq, Thrives in Exile", New York Times.

- ↑ Mottola, R.M. (Summer, Fall 2008). "Constructing the Middle Eastern Oud with Peter Kyvelos". American Lutherie (94, 95).

See also

- Qanbūs

External links

- Oud Playing Learn to Play the Oud by ear (For beginners, DVD)].

- NileCart Egyptian oud gallery.

- Alsiadi's Music Scores Alsiadi's classical Arabic & Middle Eastern music scores

- Al-Oud/The Oud a website by Dr David Parfitt

- Maqam World a website by Johnny Farraj, Najib Shaheen, Sami Abu Shumays and Tareq Abboushi

- The Ud (Oud), its players and recordings

- Iranian Oud a website by Majid Yahyanejad

- Mike's Ouds, includes Oud Forums

- Brian Prunka Oud page

- FERNWOOD An American music group that uses ouds in their music.

- Oud Cafe, an educational website dedicated to the practical techniques of Oud playing and the performance of Ottoman classical and Aegean traditional music

- Oso Varoun Ta Sidera

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||