Optic nerve

| Nerve: Optic Nerve | |

|---|---|

|

|

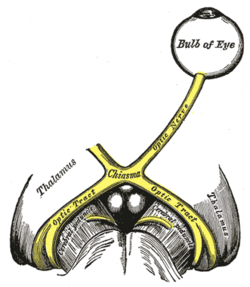

| The left optic nerve and the optic tracts. | |

| Optic nerve leaving the back of a calf eye (from dissection). | |

| Latin | nervus opticus |

| Gray's | subject #197 882 |

| MeSH | Optic+Nerve |

The optic nerve, also called cranial nerve II, is the nerve that transmits visual information from the retina to the brain.

Contents |

Anatomy

The optic nerve is the second of twelve paired cranial nerves but is considered to be part of the central nervous system as it is derived from an outpouching of the diencephalon during embryonic development. Consequently, the fibers are covered with myelin produced by oligodendrocytes rather than the Schwann cells of the peripheral nervous system. Similarly, the optic nerve is ensheathed in all three meningeal layers (dura, arachnoid, and pia mater) rather than the epineurium, perineurium, and endoneurium found in peripheral nerves. This is an important issue, as fiber tracks of the mammalian central nervous system (as opposed to the peripheral nervous system) are incapable of regeneration and hence optic nerve damage produces irreversible blindness. The fibers from the retina run along the optic nerve to nine primary visual nuclei in the brain, whence a major relay inputs into the primary visual cortex.

The optic nerve is composed of retinal ganglion cell axons and Portort cells. It leaves the orbit (eye) via the optic canal, running postero-medially towards the optic chiasm where there is a partial decussation (crossing) of fibers from the nasal visual fields of both eyes. Most of the axons of the optic nerve terminate in the lateral geniculate nucleus from where information is relayed to the visual cortex. Its diameter increases from about 1.6 mm within the eye, to 3.5 mm in the orbit to 4.5 mm within the cranial space. The optic nerve component lengths are 1 mm in the globe,24 mm in the orbit, 9 mm in the optic canal and 16 mm in the cranial space before joining the optic chiasm. There, partial decussation occurs and about 53% of the fibers cross to form the optic tracts. Most of these fibres terminate in the lateral geniculate body.

From the lateral geniculate body, fibers of the optic radiation pass to the visual cortex in the occipital lobe of the brain. More specifically, fibers carrying information from the contralateral superior visual field traverse Meyer's loop to terminate in the lingual gyrus below the calcarine fissure in the occipital lobe, and fibers carrying information from the contralateral inferior visual field terminate more superiorly.

Physiology (and an unexplained anomaly)

The eye's blind spot is a result of the absence of retina where the optic nerve leaves the eye. This is because there are no photoreceptors in this area.

The optic nerve contains 1.2 million nerve fibers. This number is low compared to the roughly 100 million photoreceptors in the retina,[1] and implies that substantial pre-processing takes place in the retina before the signals are sent to the brain through the optic nerve. There is however an alternative explanation which might conceivably account for this apparent large discrepancy. In commercial communication-channels, there are ways of vastly increasing the signal-capacity (e.g. by using multiple-or-changed modes or frequencies), and there is a case for believing that may be occurring here. See the Appendix, below. In any case, this is an anomaly — and that arguably calls for investigation along any promising lines-of-enquiry.

Role in disease

Damage to the optic nerve typically causes permanent and potentially severe loss of vision, as well as an abnormal pupillary reflex, which is diagnostically important. The type of visual field loss will depend on which portions of the optic nerve were damaged. Generally speaking:

- Damage before the optic chiasm causes loss of vision in the visual field of the same side only.

- Damage in the chiasm causes loss of vision laterally in both visual fields (bitemporal hemianopia). It may occur in large pituitary adenomata.

- Damage after the chiasm causes loss of vision on one side but affecting both visual fields: the visual field affected is located on the opposite side of the lesion.

Injury to the optic nerve can be the result of congenital or inheritable problems like Leber's Hereditary Optic Neuropathy, glaucoma, trauma, toxicity, inflammation, ischemia, infection (very rarely), or compression from tumors or aneurysms. By far, the three most common injuries to the optic nerve are from glaucoma, optic neuritis (especially in those younger than 50 years of age) and anterior ischemic optic neuropathy (usually in those older than 50).

Glaucoma is a group of diseases involving loss of retinal ganglion cells causing optic neuropathy in a pattern of peripheral vision loss, initially sparing central vision.

Optic neuritis is inflammation of the optic nerve. It is associated with a number of diseases, most notably multiple sclerosis.

Anterior Ischemic Optic Neuropathy is a particular type of infarct that affects patients with an anatomical predisposition and cardiovascular risk factors.

Ophthalmologists, particularly those sub specialists who are neuro-ophthalmologists, are often best suited to diagnose and treat diseases of the optic nerve.

The International Foundation for Optic Nerve Diseases IFOND sponsors research and information on a variety of optic nerve disorders and may provide general direction.

Additional images

Appendix: A possible explanation for the "inadequate" signal capacity of optic nerves

(See the anomaly mentioned above in the "Physiology" section).

A theoretically possible double-mode (multiplexed) signal-transmission

Myelinated nerve fibres are very like miniature versions of coaxial cables such as those used for TV aerials or for underwater telegraph-signalling in the 1800s. In fact, neurophysiologists still use Lord Kelvin's cable formula of the 1860s in calculations concerning saltatory conduction of myelinated nerve-fibres. Thus it seems appropriate to invoke any other theoretical peculiarities exhibited by coaxial cables.

Historical background and precedent

Kelvin's formula for trans-Atlantic cables was a simplification based on the apparently-reasonable assumption that frequencies would be fairly low (based on manual Morse-signalling) so that any inductance ("L") would be negligible. However if we do use much higher frequencies (what we would now call "Radio Frequencies"), then "L" becomes very important, thus allowing new transmission modes (effectively fibre-optics) [2][3] — and incidentally leading to the invention of radio as a by-product, as demonstrated by Heinrich Hertz in 1888.

Thus trans-Atlantic cables were capable of operating in two rather-different modes (and the new method was much more efficient, with a much greater "bandwidth"). However it took a prolonged effort by Oliver Heaviside to get this view accepted despite vigorous opposition from the then senior electrician of the British Post Office, Sir William Preece.[4]

Application to nerve-fibre signal capacity — perhaps explaining the anomaly

For high-frequency transmission in coaxial cables, the wave-length needs to be roughly comparable to the cable diameter. For myelinated axons (with diameters mostly in the 1-to-10 micrometre range) this suggests that the relevant radiation will be Infra-Red rather than the familiar Radio-Frequency. In any case, this would offer ample scope for broadband facilities — though we cannot yet tell whether nature has chosen to take advantage of this opportunity. Moreover, this IR would seem to be compatible with the quantum jumps which might be expected from any biochemical "switching"-or-"commands". Clearly if this extra mode is available, then there will be less need for pre-processing in the retina, though it is well known that some important pre-processing does take place there, and that at least some of the communication is via action-potentials. In any case, it is most unlikely that any visible-light signals would be transmitted this way, if only because their wavelengths would be too short.

Other indirect evidence for this alternative signal-mode

There is no systematic direct evidence for this notion; but it has prompted promising unexpected solutions in other related fields, which may be seen as indicative:

- If IR is present-in-force, then it could be expected to produce a byproduct of optical interference effects in certain circumstances. That could explain how myelin geometry is regulated — a mystery since 1905 and earlier.[5][6]

- Insects' "Sixth Sense" and Infra-Red. P.S.Callahan and E.R.Laithwaite offered a persuasive case that when insects detect their mates at long-distance (>"100 yards"), they are using tuned IR-detection (apparently via fluorescent[7] effects of the pheromones). This idea was supposedly killed off by a sudden-death debate in 1977; but that debate has since been shown as faulty on both sides, so it now seems clear that Callahan was essentially correct on his main point.[8] This offers a precedent for the usefulness of IR in bio-communication.

- IR and Insect Intelligence? There is some suggestion that insects also may have a dual-mode nervous system — but with chitin substituting for the myelin found within vertebrates. Moreover, if they are indeed directly detecting IR and partially "thinking" via IR, why bother with any intervening action-potentials?! That could explain why Callahan was unable to detect any action-potentials between his IR stimulus and the observed behavioural reaction! (though there was no such action-potential deficiency for visible light).[9][10]

References

- ↑ Jonas JB, Schneider U, Naumann GOH (1992) Count and density of human retinal photoreceptors. Graefe's Arch Clin Exp Ophthalmol 230:505-510.

- ↑ Traill, R.R. (1977/1980/2006) Towards a theoretical explanation of electro-chemical interaction in memory-use: The postulated role of infra-red components and molecular evolution; Monograph #24, Cybernetics Department, Brunel University;[1] — or as Part B of thesis:[2]

- ↑ Traill, R.R. (1988). "The case that mammalian intelligence is based on sub-molecular coding and fibre-optic capabilities of myelinated nerve axons", Speculations in Science and Technology, 11(3), 173-181.

- ↑ See (e.g.) Yavetz, I. (1995) From Obscurity to Enigma: The work of Oliver Heaviside, 1872-1889. Birkhäuser Verlag: Basel; pages 247-263.

- ↑ Donaldson, H.H., and G.W.Hoke (1905). "The areas of the axis cylinder and medullary sheath as seen in cross sections of the spinal nerves of vertebrates". Journal of Comparative Neurology, 15, 1-

- ↑ Traill, R.R. (2005 March). Strange regularities in the geometry of myelin nerve-insulation — a possible single cause. Ondwelle: Melbourne. [3]

- ↑ Note that fluorescence requires both a suitable fluorescent material (a pheromone in this case) and a suitable radiation-source to power it. Such double-requirements are one source of confusion. The issue is also complicated by olfaction: It is, of course also possible to follow a pheromone by smell in the conventional way, and that confounds the analysis for short-distance cases. However that possibility is eliminated for the long-range cases, as Laithwaite explains in some detail. See the cited report of the debate and its references.

- ↑ Traill, R.R. (2005 December). How Popperian positivism killed a good-but-poorly-presented theory — Insect communication by Infrared. Ondwelle: Melbourne.[4]

- ↑ ibid.: pp.13-15: "(i) How might the received IR signal be processed and perhaps affect behaviour?"

- ↑ Traill, R.R. (2008 September). Critique of the 1977 debate on infra-red 'olfaction' in insects — (Diesendorf vs. P.S.Callahan). Ondwelle: Melbourne. [Conference of the Australian Entomological Society][5]

External links

- The optic nerve on MRI

- BrainMaps at UCDavis optic%20nerve

- IFOND

- online case history - Optic nerve analysis with both scanning laser polarimetry with variable corneal compensation (GDx VCC) and confocal scanning laser ophthalmoscopy (HRT II - Heidelberg Retina Tomograph). Also includes actual fundus photos.

- Norman/Georgetown lesson3 (orbit4)

- Norman/Georgetown cranialnerves (II)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||