Oligocene

|

The Oligocene is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present. As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the period are well identified but the exact dates of the start and end of the period are slightly uncertain. The name Oligocene comes from the Greek ὀλίγος (oligos, few) and καινός (kainos, new), and refers to the sparsity of additional modern mammalian faunas after a burst of evolution during the Eocene. The Oligocene follows the Eocene epoch and is followed by the Miocene epoch. The Oligocene is the third and final epoch of the Paleogene period.

The Oligocene is often considered an important time of transition, a link between "[the] archaic world of the tropical Eocene and the more modern-looking ecosystems of the Miocene."[1] The Oligocene change in ecosystems is a global expansion of grasslands, and a regression of tropical broad leaf forests to the equatorial belt.

The start of the Oligocene is marked by a major extinction event, a faunal replacement of European with Asian fauna except for the endemic rodent and marsupial families called the Grande Coupure. The Oligocene-Miocene boundary is not set at an easily identified worldwide event but rather at regional boundaries between the warmer late Oligocene [26,23 Ma] and the relatively cooler Miocene.

| Paleogene period | ||

|---|---|---|

| Paleocene epoch | Eocene epoch | Oligocene epoch |

| Danian | Selandian Thanetian |

Ypresian | Lutetian Bartonian | Priabonian |

Rupelian | Chattian |

Subdivisions

Oligocene faunal stages from youngest to oldest are:

| Chattian or Late Oligocene | (28.4 ± 0.1 – 23.03 mya) |

| Rupelian or Early Oligocene | (33.9 ± 0.1 – 28.4 ± 0.1 mya) |

Climate

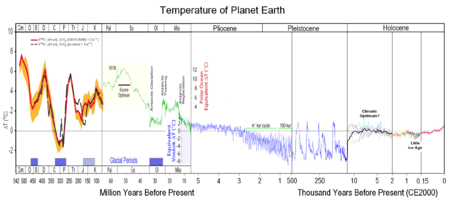

The Paleogene Period general temperature decline is interrupted by a Oligocene 7M-year stepwise climate change. A deeper 8.2oC 0.4M-year temperature depression leads the 2oC 7M-year stepwise climate change 33.5Ma.[2][3] The stepwise climate spanned 7M-years 25.5Ma thru 32.5Ma as depicted in the PaleoTemps chart. The Oligocene climate change was a global [4] increase in ice volume and a 55m decrease in sea level (35.7-33.5Ma) with a closely related (25.5-32.5Ma) temperature depression. [5] The 7M-year depression abruptly terminated within 1-2M-year of the La Garita Caldera volcanism event 28-26 Ma. The Oligocene Miocene boundary climate was relatively stable.

Paleogeography

During this period, the continents continued to drift toward their present positions. Antarctica continued to become more isolated and finally developed a permanent ice cap.(Haines)

Mountain building in western North America continued, and the Alps started to rise in Europe as the African plate continued to push north into the Eurasian plate, isolating the remnants of the Tethys Sea. A brief marine incursion marks the early Oligocene in Europe. Oligocene marine exposures are rare in North America. There appears to have been a land bridge in the early Oligocene between North America and Europe since the faunas of the two regions are very similar. During sometime in the Oligocene, South America was finally detached from Antarctica and drifted north towards North America. It also allowed the Antarctic Circumpolar Current to flow, rapidly cooling the continent.

Flora

Angiosperms continued their expansion throughout the world; tropical and sub-tropical forests were replaced by temperate deciduous woodlands. Open plains and deserts became more common. Grasses expanded from the water-bank habitat in the Eocene and moved out into open tracts; however even at the end of the period it was not quite common enough for modern savanna.(Haines)

In North America, subtropical species dominated with cashews and lychee trees present, and temperate trees such as roses, beech and pine were common. The legumes of the pea and bean family spread, and sedges, bulrushes and ferns continued their ascent.

Fauna

Important Oligocene land faunas are found on all continents except Australia. Even more open landscapes allowed animals to grow to larger sizes than they had earlier in the Paleogene.(Haines) Marine faunas became fairly modern, as did terrestrial vertebrate faunas in the northern continents. This was probably more as a result of older forms dying out than as a result of more modern forms evolving.

South America was apparently isolated from the other continents and evolved a quite distinct fauna during the Oligocene.

Reptiles were abundant in the Oligocene. Snakes and lizards diversified to a degree.

Mammals included:Brontotherium, Indricotherium, Entelodont, Hyaenodon, Mesohippus. Elephant-like forms, Proboscidea, were present.

The Oligocene oceans resembled today's fauna, such as the bivalves. The baleen and toothed cetaceans (whales) just appeared, and their ancestors, the Archaeoceti cetaceans remained relatively common but their numbers were falling as the Oligocene progressed because of climate changes and competition with today's modern cetaceans and the Charcharinid sharks, which also appeared in this epoch. Pinnipeds probably appeared near the end of the epoch from a bear-like or otter-like ancestor.

Oceans

Oceans continued to cool, particularly around Antarctica.

Impact Events

Recorded extraterrestrial impacts:

- Nunavut, Canada (23 Ma, crater 24 km diameter,)

Supervolcanic explosions

La Garita Caldera (28 thru 26 million years ago, VEI=9.2)[6]

See also

- List of fossil sites (with link directory)

- Turgai Sea

References

- ↑ Haines, Tim; Walking with Beasts: A Prehistoric Safari, (New York: Dorling Kindersley Publishing, Inc., 1999)

- ↑ A.Zanazzi (et al) 2007 'Large Temperature Drop across the Eocene Oligocene in central North America' Nature, Vol. 445, 8 February 2007

- ↑ C.R.Riesselman (et al) 2007 'High Resolution stable isotoper and carbonate variability during the early Oligocene climate transition: Walvis Ridge (ODP Site 1263) USGS OF-2007-1047

- ↑ Lorraine E. Lisiecki Nov 2004; A Pliocene-Pleistocene stack of 57 globally distributed benthic δ18O records Brown University, PALEOCEANOGRAPHY, VOL. 20

- ↑ Kenneth G. Miller Jan-Feb 2006; Eocene–Oligocene global climate and sea-level changes St. Stephens Quarry, Alabama GSA Bulletin, Rutgers University, NJ [1]

- ↑ Breining, Greg (2007). "Most-Super Volcanoes" (in English). Super Volcano: The Ticking Time Bomb Beneath Yellowstone National Park. St. Paul, MN: Voyageur Press. pp. 256 pg. ISBN 978-0-7603-2925-2.

- Ogg, Jim; June, 2004, Overview of Global Boundary Stratotype Sections and Points (GSSP's) http://www.stratigraphy.org/gssp.htm Accessed April 30, 2006.