Observable universe

| Physical cosmology | ||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

| Universe · Big Bang Age of the Universe Timeline of the Big Bang Ultimate fate of the universe

|

||||||||||||||

| Earth in the Universe |

|---|

| Universe |

| Observable universe |

| Large-scale structures |

| Virgo Supercluster |

| Local Group |

| Milky Way Galaxy |

| Orion Arm of the Milky Way |

| Gould Belt |

| Local Bubble |

| Local Interstellar Cloud |

| Solar System |

| Earth |

In Big Bang cosmology, the observable universe is the region of space bounded by a sphere, centered on the observer, that is small enough that we might observe objects in it, i.e. there has been sufficient time for a signal emitted from the object at any time after the Big Bang, and moving at the speed of light, to have reached the observer by the present time. Every position has its own observable universe which may or may not overlap with the one centered around the Earth.

The word observable used in this sense has nothing to do with whether modern technology actually permits us to detect radiation from an object in this region. It simply means that it is possible in principle for light or other radiation from the object to reach an observer on Earth. In practice, we can only observe objects as far as the surface of last scattering, before which the universe was opaque to photons. However, it may be possible to infer information from before this time through the detection of gravitational waves which also move at the speed of light.

Contents |

The universe versus the observable universe

Both popular and professional research articles in cosmology often use the term "universe" to mean "observable universe". This can be justified on the grounds that we can never know anything by direct experimentation about any part of the universe that is causally disconnected from us, although many credible theories, such as cosmic inflation, require a universe much larger than the observable universe. No evidence exists to suggest that the boundary of the observable universe corresponds precisely to the physical boundary of the universe (if such a boundary exists); this is exceedingly unlikely in that it would imply that Earth is exactly at the center of the universe, in violation of the cosmological principle. It is likely that the galaxies within our visible universe represent only a minuscule fraction of the galaxies in the universe.

It is also possible that the universe is smaller than the observable universe. In this case, what we take to be very distant galaxies may actually be duplicate images of nearby galaxies, formed by light that has circumnavigated the universe. It is difficult to test this hypothesis experimentally because different images of a galaxy would show different eras in its history, and consequently might appear quite different. A 2004 paper [1] claims to establish a lower bound of 24 gigaparsecs (78 billion light-years) on the diameter of the whole universe, making it, at most, only slightly smaller than the observable universe. This value is based on matching-circle analysis of the WMAP data.

Size

The comoving distance from Earth to the edge of the visible universe (also called particle horizon) is about 14 billion parsecs (46.5 billion light-years) in any direction.[2] This defines a lower limit on the comoving radius of the observable universe, although as noted in the introduction, it's expected that the visible universe is somewhat smaller than the observable universe since we only see light from the cosmic microwave background radiation that was emitted after the time of recombination, giving us the spherical surface of last scattering (gravitational waves could theoretically allow us to observe events that occurred earlier than the time of recombination, from regions of space outside this sphere). The visible universe is thus a sphere with a diameter of about 28 billion parsecs (about 93 billion light-years). Since space is roughly flat, this size corresponds to a comoving volume of about

or about 3×1080 cubic meters.

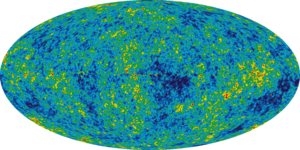

The figures quoted above are distances now (in cosmological time), not distances at the time the light was emitted. For example, the cosmic microwave background radiation that we see right now was emitted at the time of recombination, 379,000[3] years after the Big Bang, which occurred around 13.7 billion years ago. This radiation was emitted by matter that has, in the intervening time, mostly condensed into galaxies, and those galaxies are now calculated to be about 46 billion light-years from us. To estimate the distance to that matter at the time the light was emitted, a mathematical model of the expansion must be chosen and the scale factor, a(t), calculated for the selected time since the Big Bang, t. For the observationally-favoured Lambda-CDM model, using data from the WMAP satellite, such a calculation yields a scale factor change of approximately 1292. This means the universe has expanded to 1292 times the size it was when the CMBR photons were released. Hence, the most distant matter that is observable at present, 46 billion light-years away, was only 36 million light-years away from the matter that would eventually become Earth when the microwaves we are currently receiving were emitted.

Misconceptions

Many secondary sources have reported a wide variety of incorrect figures for the size of the visible universe. Some of these are listed below.

- 13.7 billion light-years. The age of the universe is about 13.7 billion years. While it is commonly understood that nothing travels faster than light, it is a common misconception that the radius of the observable universe must therefore amount to only 13.7 billion light-years. This reasoning only makes sense if the universe is the flat spacetime of special relativity; in the real universe, spacetime is highly curved on cosmological scales, which means that 3-space (which is roughly flat) is expanding, as evidenced by Hubble's law. Distances obtained as the speed of light multiplied by a cosmological time interval have no direct physical significance. [4]

- 15.8 billion light-years. This is obtained in the same way as the 13.7 billion light year figure, but starting from an incorrect age of the universe which was reported in the popular press in mid-2006[5] [6] [7]. For an analysis of this claim and the paper that prompted it, see [8].

- 27 billion light-years. This is a diameter obtained from the (incorrect) radius of 13.7 billion light-years.

- 78 billion light-years. This is a lower bound for the size of the whole universe, based on the estimated current distance between points that we can see on opposite sides of the cosmic microwave background radiation (CMBR), so this figure represents the diameter of the sphere formed by the CMBR. If the whole universe is smaller than this sphere, then light has had time to circumnavigate it since the big bang, producing multiple images of distant points in the CMBR, which would show up as patterns of repeating circles.[9] Cornish et al looked for such an effect at scales of up to 24 gigaparsecs (78 billion light years) and failed to find it, and suggested that if they could extend their search to all possible orientations, they would then "be able to exclude the possibility that we live in a universe smaller than 24 Gpc in diameter". The authors also estimated that with "lower noise and higher resolution CMB maps (from WMAP's extended mission and from Planck), we will be able to search for smaller circles and extend the limit to ~28 Gpc."[1] This estimate of the maximum diameter of the CMBR sphere that will be visible in planned experiments corresponds to a radius of 14 gigaparsecs, the same number given in the previous section.

- 156 billion light-years. This figure was obtained by doubling 78 billion light-years on the assumption that it is a radius. Since 78 billion light-years is already a diameter, the doubled figure is incorrect. This figure was very widely reported.[10] [11] [12]

- 180 billion light-years. This estimate accompanied the age estimate of 15.8 billion years in some sources;[13] it was obtained by incorrectly adding 15 percent to the incorrect figure of 156 billion light years.

Matter content

The observable universe contains about 3 to 7 × 1022 stars (30 to 70 billion trillion stars),[14] organized in more than 80 billion galaxies, which themselves form clusters and superclusters.[15]

Two back-of-the-envelope calculations give the number of atoms in the observable universe to be around 1080.

- Observations of the cosmic microwave background from the Wilkinson Microwave Anisotropy Probe suggest that the spatial curvature of the universe is very close to zero, which in current cosmological models implies that the value of the density parameter must be very close to a certain critical value. This works out to 9.9×10−27 kilograms/meter3[16], which would be equal to about 5.9 hydrogen atoms per cubic meter. Analysis of the WMAP results suggests that only about 4.6% of the critical density is in the form of normal atoms, while 23% is thought to be made of cold dark matter and 72% is thought to be dark energy,[16] so this leaves 0.27 hydrogen atoms/m3. Multiplying this by the volume of the visible universe, you get about 8×1079 hydrogen atoms.

- A typical star has a mass of about 2×1030 kg, which is about 1×1057 atoms of hydrogen per star. A typical galaxy has about 400 billion stars so that means each galaxy has 1×1057 × 4×1011 = 4×1068 hydrogen atoms. There are possibly 80 billion galaxies in the Universe, so that means that there are about 4×1068 × 8×1010 = 3×1079 hydrogen atoms in the observable Universe. But this is definitely a lower limit calculation, and it ignores many possible atom sources. [17]

Mass of the observable universe

The mass of the matter in the observable universe can be estimated based on density and size.[18]

Estimation based on the measured stellar density

One way to calculate the mass of the visible matter which makes up the observable universe is to assume a mean solar mass and to multiply that by an estimate of the number of stars in the observable universe. The estimate of the number of stars in the universe is derived from the volume of the observable universe

and a stellar density calculated from observations by the Hubble Space Telescope

yielding an estimate of the number of stars in the observable universe of 9 × 1021 stars (9 billion trillion stars).

Taking the mass of Sol (2 × 1030 kg) as the mean solar mass (on the basis that the large population of dwarf stars balances out the population of stars whose mass is greater than Sol) and rounding the estimate of the number of stars up to 1022 yields a total mass for all the stars in the observable universe of 3 × 1052 kg.[19] However, as noted in the "matter content" section, the WMAP results in combination with the Lambda-CDM model predict that less than 5% of the total mass of the observable universe is made up of visible matter such as stars, the rest being made up of dark matter and dark energy.

Sir Fred Hoyle calculated the mass of an observable steady-state universe using the formula

which can also be stated as

See also

- Particle horizon

- Event horizon of the universe

- Causality (physics)

- Hubble volume

- Large-scale structure of the cosmos

- Observation

- Multiverse

- Open multiverse

- Nine Million Bicycles (a physicist challenges the scientific accuracy of some song lyrics)

- Universe

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Neil J. Cornish, David N. Spergel, Glenn D. Starkman, and Eiichiro Komatsu, Constraining the Topology of the Universe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 92, 201302 (2004). astro-ph/0310233

- ↑ Lineweaver, Charles; Tamara M. Davis (2005). "Misconceptions about the Big Bang". Scientific American. Retrieved on 2008-11-06.

- ↑ Abbott, Brian (May 30, 2007). "Microwave (WMAP) All-Sky Survey". Hayden Planetarium. Retrieved on 2008-01-13.

- ↑ Ned Wright, "Why the Light Travel Time Distance should not be used in Press Releases".

- ↑ SPACE.com - Universe Might be Bigger and Older than Expected

- ↑ Big bang pushed back two billion years - space - 04 August 2006 - New Scientist Space

- ↑ 2 billion years added to age of universe

- ↑ Edward L. Wright, "An Older but Larger Universe?".

- ↑ Bob Gardner's "Topology, Cosmology and Shape of Space" Talk, Section 7

- ↑ SPACE.com - Universe Measured: We're 156 Billion Light-years Wide!

- ↑ New study super-sizes the universe - Space.com - MSNBC.com

- ↑ BBC NEWS | Science/Nature | Astronomers size up the Universe

- ↑ Space.com - Universe Might be Bigger and Older than Expected

- ↑ "Astronomers count the stars", BBC News (July 22, 2003). Retrieved on 2006-07-18.

- ↑ How many galaxies in the Universe? says "the Hubble telescope is capable of detecting about 80 billion galaxies. In fact, there must be many more than this, even within the observable Universe, since the most common kind of galaxy in our own neighborhood is the faint dwarfs which are difficult enough to see nearby, much less at large cosmological distances."

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 WMAP- Content of the Universe

- ↑ Matthew Champion, "Re: How many atoms make up the universe?", 1998

- ↑ McPherson, Kristine (2006). "Mass of the Universe". The Physics Factbook.

- ↑ . "On the expansion of the universe" (PDF). NASA Glenn Research Centre.

- ↑ Helge Kragh (1999-02-22). Cosmology and Controversy: The Historical Development of Two Theories of the Universe. Princeton University Press. pp. 212. ISBN 0-691-00546-X.

External links

- Cosmology FAQ

- Hubble, VLT and Spitzer Capture Galaxy Formation in the Early Universe

- Star Survey reaches 70 sextillion

- Inflation and the Cosmic Microwave Background, Lineweaver 2003

- Animation of the cosmic light horizon

- Logarithmic Maps of the Universe

|

||||||||