Nuremberg Laws

| The Holocaust |

|---|

| Early elements |

| Racial policy · Nazi eugenics · Nuremberg Laws · Forced euthanasia · Concentration camps (list) |

| Jews |

| Jews in Nazi Germany (1933–1939) |

|

Pogroms: Kristallnacht · Bucharest · Dorohoi · Iaşi · Kaunas · Jedwabne · Lviv |

|

Ghettos: Łachwa · Łódź · Lwów · Kraków · Budapest · Theresienstadt · Kovno · Vilna · Warsaw |

|

Einsatzgruppen: Babi Yar · Rumbula · Ponary · Odessa · Erntefest · Ninth Fort · |

|

Final Solution: Wannsee · Operation Reinhard · Holocaust trains |

|

Concentration camps: Resistance: Jewish partisans · Ghetto uprisings (Warsaw) |

|

End of World War II: Death marches · Berihah · Displaced persons |

| Other victims |

|

Roma · Homosexuals · Disabled individuals · Slavs in Eastern Europe · Poles · Soviet POWs · Jehovah's Witnesses · Serbs |

| Responsible parties |

|

Nazi Germany: Adolf Hitler · Heinrich Himmler · Ernst Kaltenbrunner · Reinhard Heydrich · Adolf Eichmann · Schutzstaffel · Gestapo · Sturmabteilung · Nazi Party · Rudolf Höss Collaborators Aftermath: Nuremberg Trials · Denazification · Reparations Agreement |

| Lists |

| Survivors · Victims · Rescuers |

| Resources |

| The Destruction of the European Jews Functionalism versus intentionalism |

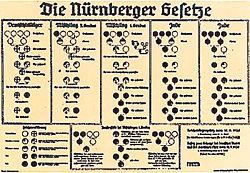

The Nuremberg Laws (German: Nürnberger Gesetze) of 1935 were laws passed in Nazi Germany. They used a pseudoscientific basis for racial discrimination against Jewish people. The laws classified people as German if all four of their grandparents were of "German blood" (white circles on the chart), while people were classified as Jews if they descended from three or four Jewish grandparents (black circles in top row right). A person with one or two Jewish grandparents was a Mischling, a crossbreed, of "mixed blood".

Contents |

Introduction and History

During the spring and summer of 1933, disenchantment with how the Third Reich had developed in practice as opposed to what had been promised had led to many in the Nazi Party, especially the Alte Kämpfer (Old Fighters; i.e those who joined the Party before 1930, and who tended to be the most ardent anti-Semitics in the Party), and the SA into lashing out against Germany's Jewish minority as a way of expressing their frustrations against a group that the authorities would not generally protect.[1] A Gestapo report from the spring of 1935 stated that the rank and file of the Nazi Party would "set in motion by us from below" a solution to the "Jewish problem", "that the government would then have to follow".[2] As a result, Nazi Party activists and SA members started a major wave of assaults, vandalism and boycotts against German Jews.[3] A conference of ministers was held on August 20 1935 to discuss the negative economic effects of Party actions against Jews. Adolf Wagner, the Party representative at the conference, argued that such effects would cease, once the government decided on a firm policy against the Jews.

Dr. Hjalmar Schacht, the Economics Minister, criticized arbitrary behavior by Party members as this inhibited his policy of rebuilding Germany's economy.[4] It made no economic sense since Jews were believed to have certain entrepreneurial skills that could be usefully employed to further his policies. Schacht made no moral condemnation of Jewish policy and advocated the passing of legislation to clarify the situation. Following complaints from Dr. Schacht plus reports that the German public did not approve of the wave of anti-Semitic violence, and that continuing police toleration of the violence was hurting the regime's popularity with the wider public, Hitler ordered a stop to "individual actions" against German Jews on August 8 1935.[5] On August 20 1935, the Interior Minister Dr. Wilhelm Frick threatened to impose harsh penalties on those Party members who ignored the order of August 8 and continued to assault Jews.[4] From Hitler's perspective, it was imperative to bring in harsh new anti-Semitic laws as a consolation prize for those Party members who were disappointed with Hitler's halt order of August 8, especially because Hitler had only reluctantly given the halt order for pragmatic reasons, and his symapthies were with the Party radicals.[4]

The Nazi Party Rally held at Nuremberg in September 1935 had featured the first session of the Reichstag held at that city since 1543. Hitler had planned to have the Reichstag pass a law making the Nazi Swastika flag the flag of the German Reich, and a major speech in support of the impending Italian aggression against Ethiopia.[6] However, at the last minute, the German Foreign Minister Baron Konstantin von Neurath persuaded Hitler to cancel his speech as being too provocative to public opinion abroad, thus leaving Hitler with the sudden need to have something else to address the historic first meeting of the Reichstag in Nuremberg since 1543, other than the Reich Flag Law.[7] On September 13 1935, Dr. Bernhard Lösener, the Interior Ministry official in charge of drafting anti-Semitic laws was hastily summoned to the Nuremberg Party Rally by plane together with another Interior Ministry official, Ministeralrat (Ministerial Counsellor) Franz Albrecht Medicus, to start drafting at once a law for Hitler to present to the Reichstag for September 15.[8] Lösener and Medicus arrived in Nuremberg on the morning of September 14 and because of the short time available for the drafting of the laws, both measures were hastily improvised (there was even a shortage of drafting paper so that menu cards had to be used).[9] On the evening of September 15, two measures were announced at the annual Party Rally in Nuremberg, becoming known as the Nuremberg Laws.[10]

The first law, The Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour,[11] prohibited marriages and extramarital intercourse between "Jews" (the name was now officially used in place of "non-Aryans") and "Germans" and also the employment of "German" females under forty-five in Jewish households. The second law, The Reich Citizenship Law [12], stripped persons not considered of German blood of their German citizenship and introduced a new distinction between "Reich citizens" and "nationals".

The Nuremberg Laws by their general nature formalized the unofficial and particular measures taken against Jews up to 1935. The Nazi leaders made a point of stressing the consistency of this legislation with the Party programme which demanded that Jews should be deprived of their rights as citizens. The laws were passed unanimously by the Reichstag, or German Parliament, in a special session held during a Nuremberg Rally. After the example of the Nuremberg Laws, The Law for Protection of the Nation was passed in Bulgaria during World War II, which also had a strong antisemitic character.

Several authors have argued that the Nuremberg Laws were inspired partly by the anti-miscegenation laws of the United States of America.[13]

The Laws for the Protection of German Blood and German Honour

|

Part of a series of articles on

Discrimination |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| General forms | ||||||

|

Ageism · Biphobia · Heterophobia · Homophobia · Racism · Sexism |

||||||

| Specific forms | ||||||

|

||||||

| Manifestations | ||||||

|

Slavery · Racial profiling · Lynching |

||||||

| Movements | ||||||

|

||||||

| Policies | ||||||

|

Discriminatory Anti-discriminatory Counter-discriminatory |

||||||

| Law | ||||||

|

Discriminatory Anti-discriminatory |

||||||

| Other forms | ||||||

|

Afrocentrism · Adultcentrism · Androcentrism · Anthropocentrism · |

||||||

| Related topics | ||||||

|

American exceptionalism · Asian fetish |

||||||

|

(September 15 1935)

Entirely convinced that the purity of German blood is essential to the further existence of the German people, and inspired by the uncompromising determination to safeguard the future of the German nation, the Reichstag has unanimously resolved upon the following law, which is promulgated herewith:

- Section 1

- Marriages between Jews and citizens of German or kindred blood are forbidden. Marriages concluded in defiance of this law are void, even if, for the purpose of evading this law, they were concluded abroad.

- Proceedings for annulment may be initiated only by the Public Prosecutor.

- Section 2

- Extramarital sexual intercourse between Jews and subjects of the state of Germany or related blood is forbidden.

(Supplementary decrees set Nazi definitions of racial Germans, Jews, and half-breeds or Mischlinge --- see the latter entry for details and citations. Jews could not vote or hold public office.)

- Section 3

- Jews will not be permitted to employ female citizens of German or kindred blood as domestic workers under the age of 45.

- Section 4

- Jews are forbidden to display the Reich and national flag or the national colours.

- On the other hand they are permitted to display the Jewish colours. The exercise of this right is protected by the State.

- Section 5

- A person who acts contrary to the prohibition of Section 1 will be punished with hard labour.

- A person who acts contrary to the prohibition of Section 2 will be punished with imprisonment or with hard labour.

- A person who acts contrary to the provisions of Sections 3 or 4 will be punished with imprisonment up to a year and with a fine, or with one of these penalties.

- Section 6

- The Reich Minister of the Interior in agreement with the Deputy Führer and the Reich Minister of Justice will issue the legal and administrative regulations required for the enforcement and supplementing of this law.

- Section 7

- The law will become effective on the day after its promulgation; Section 3, however, not until January 1 1936.

German Discrimination Against Jews

- See also: Anti-Jewish legislation in prewar Nazi Germany

While the Nuremberg Laws established for the first time very clearly who was defined as a Jew, legal discrimination against Jews had come into being earlier and steadily grew as time went on. Among other things, Jews were banned from working for the state or being employed as lawyers, doctors or journalists. Jews were prohibited from using hospitals and could not be educated past the age of 14. Public parks, libraries, beaches were closed to Jews. War memorials were to have Jewish names expunged. Even the lottery could not award winnings to Jews.[14]

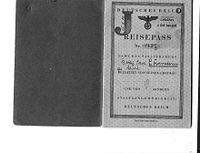

Jews were required to adopt a middle name: "Sara" for women and "Israel" for men. Their identification cards were required to have a large "J" stamped on them.[15]

Some Nazi allies in Europe also emulated the Nuremberg laws, passing similar legislation.

Existing Copies

An original typescript of the laws signed by Hitler himself was found by the 203rd Detachment of the US Army's Counter-Intelligence Corps (CIC), commanded by Martin Dannenberg, in Eichstätt, Bavaria, Germany, on April 27 1945. It was appropriated by General George S. Patton, in violation of JCS 1067. During a visit to Los Angeles, California, he secretly handed it over to the Huntington Library. The document was stored until June 26 1999 when its existence was revealed. Although legal ownership of the document has not been established, it is on permanent loan to the Skirball Cultural Center, which placed it on public display three days later.

See also

- Nazism and race

- Aryan paragraph

Endnotes

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 pages 560-561.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 page 561.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 pages 561-562.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 page 563

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 page 563

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 page 567

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 pages 567-568

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 pages 567

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 pages 568-570 & 759-760.

- ↑ Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999 pages 568

- ↑ Nuremberg Law for the Protection of German Blood and German Honor, English translation at the University of the West of England

- ↑ Reich Citizenship Law, English translation at the University of the West of England

- ↑ [1] David Hollinger (2003) Amalgamation and Hypodescent: The Question of Ethnoracial Mixture in the History of the United States, American Historical Review, Vol. 108, Iss. 5]

- ↑ "Examples of Antisemitic Legislation, 1933-1939". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved on 2008-07-12.

- ↑ "The Nuremberg Race Laws". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved on 2008-07-12.

References

- Kershaw, Ian Hitler 1889-1936: Hubris, New York: W.W Norton & Company, 1998, 1999, ISBN 0-393-04671-0.

External links

- The Nuremberg Laws on Citizenship and Race text, translated into English

- Race Laws

|

||||||||||||||