Chartres Cathedral

| Chartres Cathedral* | |

|---|---|

| UNESCO World Heritage Site | |

|

|

| State Party | |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, ii, iv |

| Reference | [http://whc.unesco.org/en/list/81

Sree 81] |

| Region** | Europe and North America |

| Inscription history | |

| Inscription | 1979 (3rd Session) |

| * Name as inscribed on World Heritage List. ** Region as classified by UNESCO. |

|

The Cathedral of Our Lady of Chartres, (French: Cathédrale Notre-Dame de Chartres), located in Chartres, about 80 kilometres (50 mi) southwest of Paris, is considered one of the finest examples in all France of the Gothic style of architecture.

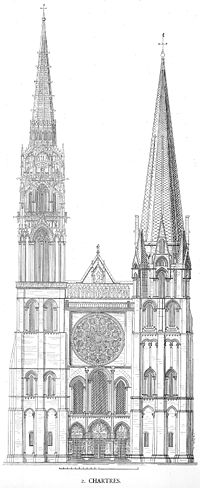

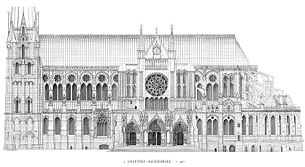

From a distance it seems to hover in mid-air above waving fields of wheat, and it is only when the visitor draws closer that the city comes into view, clustering around the hill on which the cathedral stands. Its two contrasting spires — one, a 105 metre (349 ft) plain pyramid dating from the 1140s, and the other a 113 metre (377 ft) tall early 16th century Flamboyant spire on top of an older tower — soar upwards over the pale green roof, while all around the outside are complex flying buttresses.

Contents |

History

The cathedral was the most important building in the town of Chartres. It was the centre of the economy, the most famous landmark and the focal point of almost every activity that is provided by civic buildings in towns today. In the Middle Ages, the cathedral functioned sometimes as a marketplace, with the different portals of the basilica selling different items: textiles at the northern end; fuel, vegetables and meat at the southern one. Sometimes the clergy would try, in vain, to stop the life of the markets from entering into the cathedral. Wine sellers were forbidden to sell wine in the crypt, but were allowed to do business in the nave of the church and avoid the taxes which they would have to pay if they sold it outside. Workers of various professions, such as carpenters and masons, gathered in the cathedral seeking jobs.

Pilgrimages and the legend of the Sancta Camisa

Even before the early Gothic cathedral was built, Chartres was a place of pilgrimage. When ergotism (more popularly known in the Middle Ages as "St. Anthony's fire") afflicted many victims, the crypt of the original church became a hospital to care for the sick.[1]

The church was an especially popular pilgrimage destination in the 12th century. There were four great fairs which coincided with the main feast days of the Virgin: the Purification, the Annunciation, the Assumption and the Nativity. The fairs were held in the surrounding area of the cathedral and were attended by many of the pilgrims in town for the feast days and to see the cloak of the Virgin. Thus, for hundreds of years, Chartres has been a very important Marian pilgrimage center; today the faithful still come from the world over to honour the relic.

According to legend, since 876 the cathedral's site has housed a tunic that was said to have belonged to the Blessed Virgin Mary, the Sancta Camisa. The relic had supposedly been given to the Cathedral by Charlemagne who received it as a gift during a crusade in Jerusalem. In fact, the relic was a gift from Charles the Bald and it has been asserted that the fabric came from Syria and that it had been woven during the first century AD.

When the first cathedral (it was begun in 1145 as an expansion of an old church) burned down, the relic was thought to be lost in the fire. As the story is told, the people despaired when they believed that their sacred relic had perished too. But, after three days of cooling, priests who had taken shelter in the underground vaults emerged from the ruins, amongst many witnesses, with the relic intact. All this was accounted for and announced as a miracle by a papal legate and Cardinal from Rome, who was conveniently visiting. This "miracle of survival" was taken to be a sign from Mary herself. And, in turn, the dramatic recovery of the Sancta Camisa reinvigorated enthusiasm for the cathedral project, and began to draw contributions from most of Europe, subsequently leading to an increase in the scope and magnificence of the new cathedral.

Gothic Reconstruction

Begun in the 12th century under the driving influence of the local bishop, the cathedral established several new architectural features never seen before (flying buttresses and the arches used) and pioneered new techniques for construction at high elevations above ground (such as the conversion of war machines known as trebuchets into hoisting cranes). Before this, nothing had ever been built at such heights.

Several cathedrals have occupied the site, most of which fell to that all too common scourge of town life in the Middle Ages: wooden construction without chimneys, periodic fire sweeping uncontrolled through towns without firefighting equipment, in an age reliant on burning wood for heat and cooking.

The existing cathedral at Chartres is one of various French Gothic masterpieces built because fire had destroyed its predecessors. During its early construction, the cathedral was burned down once, nearly consumed by fire a second time, and formed the focal point of several tax revolts and riots which were incited by a local countess and influential town burgers who opposed the increased influence of the church and especially the onerous taxes being used to finance its construction. The cathedral is still the seat of the Diocese of Chartres, in the Roman Catholic ecclesiastical province of Tours.

After the first cathedral of any great substance burnt down in 1020 (prior to this, other churches on the site had disappeared in smoke), a new Romanesque basilica which included a massive crypt was built under the direction of Bishop Fulbert and later under the direction of Geoffroy de Lèves.

However, following a fire in 1134 which destroyed much of the rest of the town but spared the basilica, construction of a new building on the Romanesque foundations of the earlier church was begun in 1145 in a blaze of enthusiasm dubbed the "Cult of the Carts". During this religious outburst a crowd of more than a thousand penitents dragged carts filled with building provisions including stones, wood, grain, etc. to the site.[2]

Disaster struck yet again on the night of June 10, 1194, when lightning created a blaze that left only the west towers, the façade between them, and the crypt. The fire destroyed all but the west front of the cathedral (and much of the town), so that part is in the "early Gothic" style. The body of the cathedral was rebuilt between 1194 and 1220, a comparatively short span for medieval cathedrals. It has a ground area of 10,875 m² (117,058 sq ft)

Rebuilding, with the help of donations from all over France, began almost immediately, using the plans laid out by the first architect, still anonymous, in order to preserve the harmonious aspect of the Cathedral. The enthusiasm for the project was such that the people of the city voluntarily gathered to haul the stone needed from local quarries 8 km (5 miles) away.

Work began first on the nave and by 1220 the main structure was complete, with the old crypt, along with the mid-12th-century Royal Portal which had also escaped the fire, incorporated into the new building. On October 24, 1260, in the presence of King Louis IX, the cathedral was finally dedicated.[3] However, the full set of spires that appears to have been planned for it in the early thirteenth century was never completed.

French Revolution

The cathedral was damaged in the Revolution when a mob began to destroy the sculpture on the north porch. This is one of the few occasions on which the anti-religious fervour was stopped by the townfolk. The Revolutionary Committee decided to blow the building up and asked a local master mason (architect) to organise it. He saved the building by pointing out that the vast amount of rubble from the demolished building would so clog the streets it would take years to clear away. However, when metal was needed for the army the brass plaque in the centre of the labyrinth was removed and melted down - our only record of what was on the plaque was Felibien's description.

The Cathedral of Chartres was therefore neither destroyed nor looted during the French Revolution and the numerous restorations have not diminished its reputation as a triumph of Gothic art. The cathedral was added to UNESCO's list of World Heritage Sites in 1979.

Description

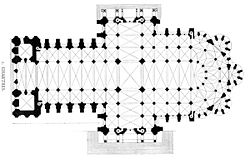

Plan

The plan is cruciform, with a 28 metres (92 ft) long nave, and short transepts to the south and north. The east end is rounded with an ambulatory which has five semi-circular chapels radiating from it. The cathedral extensively used flying buttresses in its original plan, and these supported the weight of the extremely high vaults, at the time of being built, the highest in France. The new High Gothic cathedral at Chartres used four rib vaults in a rectangular space, instead of six in a square pattern, as in earlier Gothic cathedrals such as at Laon. The skeletal system of supports, from the compound piers all the way up to the springing and transverse and diagonal ribs, allowed large spaces of the cathedral to be free for stained glass work, as well as a towering height.

The spacious nave stands 36 metres (120 ft) high, and there is an unbroken view from the western end right along to the magnificent dome of the apse in the east. Clustered columns rise dramatically from plain bases to the high pointed arches of the ceiling, directing the eye to the massive clerestory windows in the apse.

Windows

The cathedral has three large rose windows: one on the west front with a theme of The Last Judgment, one on the north transept with a theme of the Glorification of the Virgin, and one on the south transept with a theme of the Glorification of Christ.

Chartres is noted for its many large stained glass windows. Dating from the early 13th century, the glass largely escaped harm during the religious wars of the 16th century; it is said to constitute one of the most complete collections of medieval stained glass in the world, despite "modernization" in 1753 when some of it was removed by well-intentioned but misguided clergy. Of the original 186 stained glass windows, 152 survive. The windows are particularly renowned for their vivid blue colour, especially in a representation of the Madonna and Child known as the Blue Virgin Window, a traditional iconography know as the Seat of Wisdom. The Jesse Tree window is another noted window at Chartres.

Several of the windows were donated by royalty, such as the rose window at the north transept, which was a gift from the French queen Blanche of Castile. The royal influence is shown in some of the long rectangular lancet windows which display the royal symbols of the yellow fleurs-de-lis on a blue background and also yellow castles on a red background.Windows were also donated from lords, locals and tradespeople.

The windows also present the first European wheelbarrow.[4]

During the Second World War, most of the stained glass was removed from the cathedral and stored in the surrounding countryside to protect it from German bombers. The cathedral was used as a social club during the German occupation of France. At the close of the war, the windows were taken out of hiding and reinstalled.

Porches

On the doors and porches, medieval carvings of statues holding swords, crosses, books and trade tools parade adorn the portals. The sculptures on the west façade depict Christ's ascension into heaven, episodes from his life, saints, apostles, Christ in the lap of Mary and other religious scenes. Below the religious figures are statues of kings and queens, which is the reason why this entrance is known as the 'royal' portal. While these figures are based on figures from the Old Testament, they were also regarded as images of current kings and queens when they were constructed. The symbolism of showing royalty displayed slightly lower than the religious sculptures, but still very close, implies the relationship between the kings and God. It is a way of displaying the authority of royalty, showing them so close to figures of Christ, it gives the impression they have been ordained and put in place by God. Sculptures of the Seven Liberal Arts appear in the archivolt of the right bay of the Royal Portal, inidcating the influence of the school at Chartres.

Statistics

- length: 130 metres (430 ft)

- width: 32 metres (100 ft) / 46 metres (150 ft)

- nave: height 37 metres (120 ft); width 16.4 metres (54 ft)

- Ground area: 10,875 square metres (117,060 sq ft)

- Height of south-west tower: 105 metres (340 ft)

- Height of north-west tower: 113 metres (370 ft)

- 176 stained-glass windows

- rood screen: 200 statues in 41 scenes

The school of Chartres

In the Middle Ages the cathedral also functioned as an important cathedral school. Charlemagne wanted a system of education for the French people in the ninth century, and since it was difficult and costly for new schools to be built, it was easier to use already existing infrastructure. So he ordered that both cathedrals and monasteries maintain schools. Cathedral schools eventually took over from monastic schools as the main places of education. In the 11th century the education system was controlled by the clergy in cathedrals such as Chartres. The cathedral itself symbolized the school. Many French cathedral schools had specialties, and Chartres was most renowned for the study of logic. The new logic taught in Chartres was regarded by many as being even ahead of Paris. One person who was educated at Chartres was John of Salisbury, an English philosopher and writer, who had his classical training there under the tutelage of Thierry of Chartres. According to Malcolm Miller, the school was responsible for the Neoplatonic symbolism of the cathedral's west façade.

In popular culture

Orson Welles famously used Chartres as a visual backdrop and inspiration for a montage sequence in his film F For Fake. Welles’ semi-autographical verse spoke to the power of art in culture and how the work itself may be more important than the identity of its creators. Feeling that the beauty of Chartres and its unknown artisans/architects epitomized this sentiment, Welles said:

Ours, the scientists keep telling us, is a universe which is disposable. You know it might be just this one anonymous glory of all things, this rich stone forest, this epic chant, this gaiety, this grand choiring shout of affirmation, which we choose when all our cities are dust; to stand intact, to mark where we have been, to testify to what we had it in us to accomplish. Our works in stone, in paint, in print are spared, some of them for a few decades, or a millennium or two, but everything must fall in war or wear away into the ultimate and universal ash: the triumphs and the frauds, the treasures and the fakes. A fact of life ... we're going to die. "Be of good heart," cry the dead artists out of the living past. Our songs will all be silenced – but what of it? Go on singing. Maybe a man's name doesn't matter all that much.

Joseph Campbell references his spiritual experience in The Power of Myth:

I'm back in the Middle Ages. I'm back in the world that I was brought up in as a child, the Roman Catholic spiritual-image world, and it is magnificent ... That cathedral talks to me about the spiritual information of the world. It's a place for meditation, just walking around, just sitting, just looking at those beautiful things.

In the film Two for the Road, Mark Wallace (played by Albert Finney) says to his wife, Jo (Audrey Hepburn):

Nobody knows the names of the men who made it. To make something as exquisite as this without wanting to smash your stupid name all over it. All you hear about nowadays is people making names, not things.

Chartres was the primary basis for the fictional Cathedral in David Macaulay's Cathedral: The Story of Its Construction and the animated special based on this book.

Chartres was a major character in the religious thriller Gospel Truths by J. G. Sandom. The book used the Cathedral's architecture and history as clues in the search for a lost Gospel.

Chartres is one of the scalable buildings in Assassin's Creed. It resides in the fictional city of Acre in the Rich District.

References

- ↑ Favier, Jean. The World of Chartres. New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1990. p. 31. ISBN 0-8109-1796-3.

- ↑ Honour, H. and Fleming, J. The Visual Arts: A History, 7th ed., Saddle River, New Jersey: Pearson Prentice Hall, 2005.

- ↑ Favier, Jean. The World of Chartres. New York: Henry N. Abrams, 1990. p. 160. ISBN 0-8109-1796-3.

- ↑ "Wheelbarrow". John H. Lienhard. The Engines of Our Ingenuity. NPR. KUHF-FM Houston. 1990. No. 377. Transcript.

Bibliography

- Adams, Henry. Mont-Saint-Michel and Chartres. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1913 and many later editions.

- Ball, Philip. Universe of Stone. New York: Harper, 2008. ISBN 0061154296.

- Delaporte, Y. Les vitraux de la cathédrale de Chartres: histoire et description par l'abbé Y. Delaporte ... reproductions par É. Houvet. Chartres : É. Houvet, 1926. 3 volumes (consists chiefly of photographs of the windows of the cathedral)

- Houvet, E. Cathédrale de Chartres. Chelles (S.-et-M.) : Hélio. A. Faucheux, 1919. 5 volumes in 7. (consists entirely of photogravures of the architecture and sculpture, but not windows)

- Houvet, E. An Illustrated Monograph of Chartres Cathedral: (Being an Extract of a Work Crowned by Académie des Beaux-Arts). s.l.: s.n., 1930.

- James, John, The Master Masons of Chartres, West Grinstead, 1990, ISBN 0646008056.

- James, John, The contractors of Chartres, Wyong, ii vols. 1979-81, ISBN 0959600523 and 4 x

- Mâle, Emile. Notre-Dame de Chartres. New York: Harper & Row, 1983.

- Miller, Malcolm. Chartres Cathedral. New York: Riverside Book Co., 1997. ISBN 1878351540.

See also

- France in the Middle Ages

External links

- Pitt photo collection

- Chartres Cathedral at Sacred Destinations

- (English) http://www.mymaze.de/chartres_technisch_e.htm (About the labyrinth)

- Details of the Zodiac and other Chartres Windows

- Description of the outer portals Retrieved 03-08-2008

- (French) The labyrinth : a path to Jerusalem in cathedrals

|

|||||||