Northumbria

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Northumbria (sometimes spelled Northhumbria) is primarily the name of both a medieval petty kingdom of Angles, in what is now north east England and southern Scotland, and of the earldom which succeeded it when a united Anglo-Saxon kingdom became England. The name reflects the approximate southern limit to the kingdom's territory: the Humber estuary.

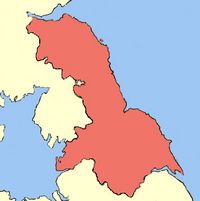

Northumbria was formed in central Great Britain in Anglo-Saxon times. At the beginning of the 7th century the two kingdoms of Bernicia and Deira were unified. (In the 12th century writings of Henry of Huntingdon the kingdom was defined as one of the Heptarchy of Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.) At its greatest the kingdom extended at least from just south of the Humber, to the River Mersey and to the Forth (roughly, Sheffield to Runcorn to Edinburgh) - and there is some evidence that it may have been much greater (see map).

The later (and smaller) earldom came about when the southern part of Northumbria (ex-Deira) was lost to the Danelaw. The northern part (ex-Bernicia) at first retained its status as a kingdom but when it become subordinate to the Danish kingdom it had its powers curtailed to that of an earldom, and retained that status when England was reunited by the Wessex-led reconquest of the Danelaw. The earldom was bounded by the River Tees in the south and the River Tweed in the north (broadly similar to the modern North East England). Much of this land was "debated" between England and Scotland, but the Earldom of Northumbria was eventually recognised as part of England by the Anglo-Scottish Treaty of York in 1237. On the northern border, Berwick-upon-Tweed, which is north of the Tweed but had changed hands many times, was defined as subject to the laws of England by the Wales and Berwick Act of 1746.

The land once part of Northumbria at its peak is now divided by modern administrative boundaries.

- North East England includes Anglian Bernicia

- Yorkshire and the Humber includes Danish Deira

- North West England includes Cumbria, though Cumbria was more of a Northumbrian colony with its own client kings for most of its history in the Early Medieval era

- Scottish Borders, West Lothian, Edinburgh, Midlothian and East Lothian cover the extreme north

In a modern sense, Northumbria is mainly used as a romantic tourist name for the North East of England, or, often, just for Northumberland, though the regional tourist organisation refers to North East England. It is also used in the names of some regional institutions : particularly the police force (Northumbria Police) which covers Northumberland and Tyne and Wear) and a university Northumbria University based in Newcastle. The local Environment Agency office, located in Newcastle Business Park, also uses the term Northumbria to describe its patch. Otherwise, the term is not used in everyday conversation, and is not the official name for the UK and EU region of North East England.

Contents |

Kingdom (654 – 878)

- See also: List of monarchs of Northumbria and Timeline of Northumbria

Northumbria was originally composed of the union of two independent kingdoms, Bernicia and Deira. Bernicia covered lands north of the Tees, whilst Deira corresponded roughly to modern-day Yorkshire. Bernicia and Deira were first united by Aethelfrith, a king of Bernicia who conquered Deira around the year 604. He was defeated and killed around the year 616 in battle at the River Idle by Raedwald of East Anglia, who installed Edwin, the son of Aella, a former king of Deira, as king.

Edwin, who accepted Christianity in 627, soon grew to become the most powerful king in England: he was recognized as Bretwalda and conquered the Isle of Man and Gwynedd in northern Wales. He was, however, himself defeated by an alliance of the exiled king of Gwynedd, Cadwallon ap Cadfan and Penda, king of Mercia, at the Battle of Hatfield Chase in 633.

King Oswald

After Edwin's death, Northumbria was split between Bernicia, where Eanfrith, a son of Aethelfrith, took power, and Deira, where a cousin of Edwin, Osric, became king. Cumbria tended to remain a country frontier with the Britons. Both of these rulers were killed during the year that followed, as Cadwallon continued his devastating invasion of Northumbria. After the murder of Eanfrith, his brother, Oswald, backed warriors sent by Domnall Brecc of Dál Riata, defeated and killed Cadwallon at the Battle of Heavenfield in 634.

Oswald expanded his kingdom considerably. He incorporated Gododdin lands northwards up to the Firth of Forth and also gradually extended his reach westward, encroaching on the remaining Cumbric speaking kingdoms of Rheged and Strathclyde. Thus, Northumbria became not only part of modern England's far north, but also covered much of what is now the south-east of Scotland.

King Oswald re-introduced Christianity to the Kingdom by appointing St. Aidan, an Irish monk from the Scottish island of Iona to convert his people. This led to the introduction of the practices of Celtic Christianity. A monastery was established on Lindisfarne.

War with Mercia continued, however. In 642, Oswald was killed by the Mercians under Penda at the Battle of Maserfield. In 655, Penda launched a massive invasion of Northumbria, aided by the sub-king of Deira, Aethelwald, but suffered a crushing defeat at the hands of an inferior force under Oswiu, Oswald's successor, at the Battle of Winwaed. This battle marked a major turning point in Northumbrian fortunes: Penda died in the battle, and Oswiu gained supremacy over Mercia, making himself the most powerful king in England.

Religious union and eventual decline

In the year 664 a great synod was held at Whitby to discuss the controversy regarding the timing of the Easter festival. Much dispute had arisen between the practices of the Celtic church in Northumbria and the beliefs of the Roman church. Eventually, Northumbria was persuaded to move to the Roman practice, the Celtic Bishop Colman of Lindisfarne returned to Iona.

Northumbria lost control of Mercia in the late 650s, after a successful revolt under Penda's son Wulfhere, but it retained its dominant position until it suffered a disastrous defeat at the hands of the Picts at the Battle of Nechtansmere in 685; Northumbria's king, Ecgfrith (son of Oswiu), was killed, and its power in the north was gravely weakened. The peaceful reign of Aldfrith, Ecgfrith's half-brother and successor, did something to limit the damage done, but it is from this point that Northumbria's power began to decline, and chronic instability followed Aldfrith's death in 704.

In 867 Northumbria became the northern kingdom of the Danelaw, after its conquest by the brothers Halfdan Ragnarsson and Ivar the Boneless who installed an Englishman, Ecgberht, as a puppet king. Despite the pillaging of the kingdom, Viking rule brought lucrative trade to Northumbria, especially at their capital Jórvík, (York).

Earldom (930 – 1217)

- See also: Earl of Northumbria

After the English regained the territory of the former kingdom, Scots invasions reduced Northumbria to an earldom stretching from the Humber to the Tweed. Northumbria was disputed between the emerging kingdoms of England and Scotland. The land north of the Tweed was finally ceded to Scotland in 1018 as a result of the battle of Carham. Yorkshire and Northumberland were first mentioned as separate in the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle in 1065.[1])

Norman invasion and partition of the earldom

William the Conqueror became king of England in 1066. He realised he needed to control Northumbria, which had remained virtually independent of the Kings of England, to protect his kingdom from Scottish invasion. To acknowledge the remote independence of Northumbria and ensure England was properly defended from the Scots William gained the allegiance of both the Bishop of Durham and the Earl and confirmed their powers and privileges. However, anti-Norman rebellions followed. William therefore attempted to install Robert Comine, a Norman noble, as the Earl of Northumbria, but before Comine could take up office, he and his 700 men were massacred in the City of Durham. In revenge, the Conqueror led his army in a bloody raid into Northumbria, an event that became known as the harrying of the North. Ethelwin, the Anglo-Saxon Bishop of Durham, tried to flee Northumbria at the time of the raid, with Northumbrian treasures. The bishop was caught, imprisoned, and later died in confinement; his see was left vacant.

Rebellions continued, and William's son William Rufus decided to partition Northumbria. William of St. Carilef was made Bishop of Durham, and was also given the powers of Earl for the region south of the rivers Tyne and Derwent, which became the County Palatine of Durham. The remainder, to the north of the rivers, became Northumberland, where the political powers of the Bishops of Durham were limited to only certain districts, and the earls continued to rule as clients of the English throne.

The city of Newcastle was founded by the Normans in 1080 to control the region by holding the strategically important crossing point of the river Tyne.

Subsequent history

The Northumbrian region continued a history of revolt and rebellion against the government, as seen in the Rising of the North in Tudor times. A major reason was the strength of Catholicism in the area after the Reformation. Rural, thinly populated, and sharing a border with an often hostile Scotland, the region became a wild place where reivers raided across the border and outlaws took refuge from justice. However, after the union of the crowns of Scotland and England under King James VI and I peace was largely established. After the Restoration, many inhabitants of the Northumbrian region supported the Jacobite cause.

Flag

Flag of Northumbria

|

The design of the Northumbrian or Border Check is one of the earliest styles of Tartan in Northern Europe.

|

The flag of the kingdom was "a banner made of gold and purple" (or red), first recorded in the 8th century as having hung over the shrine of King Oswald. This was later interpreted as vertical stripes. A modified version (with broken vertical stripes) can be seen in the coat of arms and flag used by Northumberland County Council.

Culture

Northumbria was famed as a centre of religious learning and arts. Initially the kingdom was evangelized by monks from the Celtic Church, which led to a flowering of monastic life, and Northumbria played an important role in the formation of Insular art, a unique style combining Anglo-Saxon, Celtic, Byzantine and other elements. After the Synod of Whitby in 664 Roman church practices officially replaced the Celtic ones but the influence of the Anglo-Celtic style continued, the most famous examples of this being the Lindisfarne Gospels. The Venerable Bede (673–735) wrote his Historia ecclesiastica gentis Anglorum (Ecclesiastical History of the English People, completed in 731) in a Northumbrian monastery, and much of it focuses on the kingdom.[2]

Northumbria has its own check or tartan, which is similar to many ancient tartans (especially those from Northern Europe, such as one found near Falkirk and those discovered in Jutland that date from Roman times (and even earlier).[3][4][5][6] Modern Border Tartans are almost invariably a bold black and white check, but historically the light squares were the yellowish colour of untreated wool, with the dark squares any of a range of dark grays, blues, greens or browns; hence the alternative name of "Border Drab." At a distance the checks blend together making the fabric ideal camouflage for stalking game.[7][8]

Language

Apart from standard English, Northumbria has a series of closely related but distinctive dialects, descended from the early Germanic languages of the Angles, of which 80% of it's vocabulary is derived,[9] and Vikings with a few Brythonic and Latin loanwords. The Scots language began to diverge from early Northumbrian Middle English, which was called Ynglis as late as the early 16th century. (Until the end of the 15th century the name Scots (or Scottis) referred to Scottish Gaelic). There are many similarities between modern Scots dialects and those of Northumbria.

The major Northumbrian dialects are Geordie (Tyneside), Northern (north of the River Coquet), Western (from Allendale through Hexham up to Kielder), Southern or Pitmatic (the mining towns such as Ashington and much of Durham),[10] Mackem (Wearside), Smoggie (Teesside) and Tyke. To an outsider's ear the similarities far outweigh the differences between the dialects. As an example of the difference in the softer South County Durham/Wearside the English 'book' is pronounced 'bewk', in Geordie it becomes 'bouk' while in the Northumbrian it is 'byuk'.

Due to the roots of Northumbrian dialects, it is often said that visitors from Scandinavian countries and the Netherlands often find it much easier to understand the English of Northumbria than the rest of the country. An example is the Geordie 'gan hyem' (to go home), which sounds similar to the Danish and Norwegian 'gå hjem', and means the same. In fact, many northeasterners report that when abroad they are often mistaken for Norwegians or Danes. This occurance is said to be particularly common with German speakers.

See also

- Northumberland

- History of Northumberland

- Northumbrian smallpipes

- Northumbrian tartan

References

- ↑ Ekwal E, The Concise Oxford Dictionary of English Place-Names: 4th Ed, OUP, 1960, ISBN 0-19-869103-3

- ↑ Goffart, Walter. The Narrators of Barbarian History (A.D. 550&ndsh;800): Jordanes, Gregory of Tours, Bede, and Paul the Deacon. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1988. 238ff.

- ↑ Cultural Heritage

- ↑ J. P. Wild Britannia, Vol. 33, 2002 (2002)

- ↑ J. P. Wild, The Classical Quarterly, New Series, Vol. 14, No. 2 (Nov., 1964)

- ↑ Anglo-Saxon Thegn, 449–1066 A.D. By Mark Harrison, Osprey Publishing 1993, ISBN 1-855-32349-4. p. 17

- ↑ A short history of the Tartan

- ↑ The History of Scottish Tartans & Clans Tartans

- ↑ North East dialect origins and the meaning of 'Geordie'

- ↑ The Northumbrian Language Society

Further reading

- Higham, N.J., The Kingdom of Northumbria AD 350–1100 (1993) ISBN 0-86299-730-5

- Rollason, D., Northumbria, 500–1100: Creation and Destruction of a Kingdom (2003) ISBN 0-521-81335-2

External links

- Visit Northumberland - The Official Visitor Site for Northumberland

- Northumbrian Language Society

- Northumbrian Association

- Lowlands-L, An e-mail discussion list for those who share an interest in the languages & cultures of the Lowlands

- Lowlands-L in Nothumbrian

- Northumbrian Traditional Music

- Northumbrian Small Pipes Encyclopedia

|

|||||

|

|||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||