Norfolk, Virginia

| City of Norfolk | |||

|

|

|||

|

|||

| Motto: Crescas (Latin for, "Thou shalt grow.") | |||

|

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Virginia | ||

| Founded | 1682 | ||

| Incorporated | 1736 | ||

| Government | |||

| - Mayor | Paul D. Fraim (D) | ||

| Area | |||

| - City | 96.3 sq mi (249.4 km²) | ||

| - Land | 53.7 sq mi (139.2 km²) | ||

| - Water | 42.6 sq mi (110.3 km²) | ||

| Elevation | 7 ft (2.13 m) | ||

| Population (2000) | |||

| - City | 234,403 | ||

| - Density | 4,362.6/sq mi (1,684.4/km²) | ||

| - Urban | 1,047,869 | ||

| - Metro | 1,569,541 | ||

| Time zone | EST (UTC-5) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | EDT (UTC-4) | ||

| ZIP Code | 23501-23515, 23517-23521, 23523, 23529, 23541, 23551 | ||

| Area code(s) | 757 | ||

| FIPS code | 51-57000[1] | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 1497051[2] | ||

| Website: http://www.norfolk.gov/ | |||

Norfolk is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. With a population of 234,403 as of the 2000 census, it is Virginia's second-largest incorporated city.

Norfolk is located in the Hampton Roads region, named for the large natural harbor of the same name located at the mouth of Chesapeake Bay. It is one of nine cities and seven counties that constitute the Hampton Roads metropolitan area, officially known as the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC MSA. The city is bordered to the west by the Elizabeth River and to the north by the Chesapeake Bay. It also shares land borders with the independent cities of Chesapeake to its south and Virginia Beach to its east. One of the oldest of the Seven Cities of Hampton Roads, Norfolk is considered to be the historic, urban, financial, and cultural center of the region.

The city has a long history as a strategic military and transportation point. Norfolk Naval Base is the world's largest such base. The city also has the corporate headquarters of Norfolk Southern Railway, one of North America's principal Class I railroads. As the city is bordered by multiple bodies of water, Norfolk has many miles of riverfront and bayfront property. It is linked to its neighbors by an extensive network of Interstate highways, bridges, tunnels, and bridge-tunnel complexes.

Contents |

History

In 1619, the Governor for the Virginia Colony, Sir George Yeardley established four incorporations, termed citties (sic), for the developed portion of the colony. These formed the basis for colonial representative government in the newly minted House of Burgesses. What would become Norfolk was put under the Elizabeth Cittie incorporation.

In 1622, Adam Thoroughgood (1604-1640) of King's Lynn, Norfolk, England, came to Virginia as an indentured servant. At the end of his contracted servitude, he earned his freedom and became a leading citizen of the fledgling colony.

In 1634 King Charles I reorganized the colony into a system of shires. The former Elizabeth Cittie became Elizabeth City Shire. After persuading 105 people to settle in the colony, Thoroughgood was granted a large land holding along the Lynnhaven River in 1636.

When the South Hampton Roads portion of the shire was partitioned off, Thoroughgood suggested the name of his birthplace for the newly formed New Norfolk County. One year later, it split into two counties, Upper Norfolk County and Lower Norfolk County (present day Norfolk), chiefly on Thoroughgood’s recommendation.[3]

Norfolk grew in the late 1600s as a "Half Moone" fort was constructed and 50 acres (200,000 m2) were acquired in exchange for 10,000 pounds of tobacco. The House of Burgesses established "Towne of Lower Norfolk County" in 1680.[4][5] In 1691, a final county subdivision took place when Lower Norfolk County split to form Norfolk County (present day Norfolk, Chesapeake, and parts of Portsmouth) and Princess Anne County (present day Virginia Beach). Norfolk was incorporated in 1705 and in 1736, George II granted Norfolk a royal charter as a borough.[6]

By 1775, Norfolk developed into what contemporary observers argued was the most prosperous city in Virginia. It was an important port for exporting goods to the British Isles and beyond. In part because of its merchants' numerous trading ties with other parts of the British Empire, Norfolk served as a strong base of Loyalist support during the early part of the American Revolution. After fleeing the colonial capitol of Williamsburg, Lord Dunmore, the Royal Governor of Virginia, tried to reestablish control of the colony from Norfolk. Dunmore secured small victories at Norfolk but was forced into exile by the American rebels, commanded by Colonel Woodford. His departure brought an end to more than 168 years of British colonial rule in Virginia.[7]

On New Year's Day, 1776, Lord Dunmore's fleet of three ships shelled the city of Norfolk for over 8 hours. The damage from the shells, and fires started by the British and spread by the patriots, destroyed over 800 buildings, almost two-thirds of the city. The patriots destroyed the remaining buildings for strategic reasons in February.[8] Only the walls of St. Paul's Episcopal Church survived the bombardment and subsequent fires. A cannonball from the bombardment remains within the wall of St. Paul's.[9]

Following recovery from the Revolutionary War's burning, the 19th century began inauspiciously for Norfolk and her citizens. In 1804, another serious fire along the city’s waterfront destroyed some 300 buildings and the city experienced a serious economic setback.

During the 1820’s, agrarian communities across the American South suffered a prolonged recession, which caused many families to migrate to other areas. Many moved west into the Piedmont, or into Kentucky and Tennessee. Such migration also followed the exhaustion of soil due to tobacco cultivation in the Tidewater. Virginia made various attempts to phase out slavery, either through law (see Thomas Jefferson Randolph's 1832 resolution) or through "repatriation" of blacks to Africa. Many emigrants to Africa from Virginia and North Carolina embarked from the port of Norfolk. Joseph Jenkins Roberts, a native of Norfolk, was an emigrant who became the first president of Liberia.[10]

In early 1861, Norfolk voters instructed their delegate to vote for ratification of the ordinance of secession. Virginia voted to secede from the Union. In the spring of 1862, the Battle of Hampton Roads took place off the northwest shore of the city's Sewell's Point Peninsula, marking the first fight between two ironclads, the USS Monitor and the CSS Merrimack. The battle ended in a stalemate, but forever changed the course of naval warfare; from then on, warships were fortified with metal.[11] In May 1862, Norfolk Mayor William Lamb surrendered the city to General John E. Wool and Union forces. They held the city under martial law for the duration of the Civil War. Thousands of slaves escaped to Union lines to gain their freedom and set up schools in Norfolk so they could start learning before the end of the war. [12]

1907 brought both the Virginian Railway and the Jamestown Exposition to Sewell's Point. The large Naval Review at the Exposition demonstrated the peninsula's favorable location and laid the groundwork for the world's largest naval base. Commemorating the 300th anniversary of the founding of Jamestown, the exposition featured many prominent officials, including President Theodore Roosevelt, members of Congress, and diplomats from 21 countries.

By 1917, as the US built up to enter World War I, the Naval Air Station Hampton Roads had been constructed on the former exposition grounds.[13]

In the first half of the twentieth century, Norfolk expanded its borders through annexation. In 1906, the City annexed the incorporated town of Berkley, which stretched the city limits across the Elizabeth River.[14] In 1923, the city expanded to include Sewell's Point, Willoughby Spit, the town of Campostella, and the Ocean View area. The City included the Navy Base and miles of beach property fronting on Hampton Roads and Chesapeake Bay.[15] After a smaller annexation in 1959, and a 1988 land swap with Virginia Beach, the city assumed its current boundaries.[16]

With the dawn of the Interstate Highway System, new highways opened in the region. A series of bridges and tunnels constructed during fifteen years linked Norfolk with the Peninsula, Portsmouth, and Virginia Beach. In 1952, the Downtown Tunnel opened to connect Norfolk with the city of Portsmouth. In 1991, the new Downtown Tunnel/Berkley Bridge complex opened a new system of multiple lanes of highway and interchanges connecting Downtown Norfolk and Interstate 464 with the Downtown Tunnel tubes.[17] Additional bridges and tunnels included the Hampton Roads Bridge-Tunnel in 1957,[18] the Midtown Tunnel in 1962,[19]

and the Virginia Beach-Norfolk Expressway (Interstate 264 and State Route 44) in 1967.[20]

In reaction to the Supreme Court ruling in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education case which held that segregated schools were unconstitutional and order integration, Virginia pursued a policy of "massive resistance." The Virginia General Assembly prohibited state funding for integrated public schools. Norfolk's private schools had voluntarily integrated by choosing to comply with the Brown decision. In 1958, United States district courts in Virginia ordered schools to open for the first time on a racially-integrated basis. In response, Governor James Lindsay Almond, Jr. ordered the schools closed.

Six Norfolk public schools serving over 10,000 Norfolk children were closed. The Virginia Supreme Court of Appeals declared the state law to be in conflict with the state constitution and ordered all public schools to be funded, whether integrated or not. About 10 days later, Almond capitulated and asked the General Assembly to rescind several "massive resistance" laws.[21] In September 1959, 17 black children entered six previously segregated Norfolk public schools. Virginian-Pilot editor Lenoir Chambers editorialized against massive resistance and earned the Pulitzer Prize for Editorial Writing.[22]

After desegregation, and with new suburban developments beckoning, many white middle-class residents moved out of the city along new highway routes, and Norfolk's population fell. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, the advent of newer suburban shopping destinations along with freeways spelled demise for the fortunes of downtown's Granby Street commercial corridor, located just a few blocks inland from the waterfront. The opening of malls and large shopping centers drew off retail business from Granby Street.[23]

Norfolk's city leaders began a long push to revive its urban core. While Granby Street underwent decline, Norfolk city leaders focused on the waterfront and its collection of decaying piers and warehouses. Many obsolete shipping and warehousing facilities were demolished. In their place, planners created a new boulevard, Waterside Drive, along which many of the high-rise buildings in Norfolk's skyline were erected.

The City and The Rouse Company developed the Waterside festival marketplace in 1983 to attract people to the waterfront and catalyze further downtown redevelopment.[24] Other facilities opened in the ensuing years, including the Harbor Park baseball stadium, home of the Norfolk Tides Triple-A minor league baseball team. In 1995, the Park was named the finest facility in minor league baseball by Baseball America.[25]

Norfolk's efforts to revitalize its downtown have attracted acclaim from economic development and urban planning circles throughout the country. Downtown's rising fortunes helped to expand the city's revenues and allowed the city to direct attention to other neighborhoods.[26]

Geography

According to the United States Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 96.3 square miles (249.4 km²), of which, 53.7 square miles (139.2 km²) of it is land and 42.6 square miles (110.3 km²) of it (44.22%) is water. Norfolk is located at (36.885747° N, 76.2599° W)

The city is located at the southeastern corner of Virginia at the junction of the Elizabeth and James rivers, bordering the Chesapeake Bay. The Hampton Roads Metropolitan Statistical Area (officially known as the Virginia Beach-Norfolk-Newport News, VA-NC MSA) is the 34th largest in the United States, with a total population of 1,576,370. The area includes the Virginia cities of Norfolk, Virginia Beach, Chesapeake, Hampton, Newport News, Poquoson, Portsmouth, Suffolk, Williamsburg, and the counties of Gloucester, Isle of Wight, James City, Mathews, Surry, and York, as well as the North Carolina county of Currituck. The city of Norfolk is recognized as the central business district, while the Virginia Beach oceanside resort district and Williamsburg are primarily centers of tourism. Virginia Beach is the most populated city within the MSA though it functions more as a suburb.

In addition to extensive riverfront property, Norfolk has miles of bayfront resort property and beaches in the Willoughby Spit and Ocean View communities.

Climate

Norfolk has a humid subtropical climate with moderate changes of seasons. Spring arrives in March with mild days and cool nights, and by late May, the temperature has warmed up considerably to herald warm summer days. Summer temperatures can be unpleasantly hot, often topping 90 °F (32 °C) with high humidity. On average, July is the warmest month of the year, with the maximum average precipitation. Hurricanes and tropical storms usually brush Norfolk and only rarely make landfalls in the area. Days stay warm to mild until October, and fall is marked by nights once again becoming cooler. Winter is usually mild in Norfolk, with the coldest days featuring lows in the mid-upper 30s and highs in the upper 40s to low 50s. On average, the coolest month of the year is January. Norfolk's record high was 105 °F (40 °C) on August 7, 1918, and record low was -3 °F (-19 °C) recorded on January 21, 1985.[27] Snow falls every winter, although averaging only 7 inches (180 mm) per season.[28]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Record high °F | 84 | 82 | 92 | 97 | 100 | 102 | 104 | 105 | 100 | 95 | 86 | 80 | |

| Average high °F | 48 | 50 | 58 | 67 | 75 | 83 | 87 | 85 | 79 | 69 | 61 | 52 | |

| Average low °F | 32 | 34 | 40 | 48 | 58 | 66 | 71 | 70 | 65 | 53 | 44 | 36 | |

| Record low °F | -3 | 2 | 14 | 23 | 36 | 45 | 54 | 49 | 40 | 27 | 17 | 5 | |

| Precipitation inches | 3.93 | 3.34 | 4.08 | 3.38 | 3.74 | 3.77 | 5.17 | 4.79 | 4.06 | 3.47 | 2.98 | 3.03 | |

| Record high °C | 29 | 28 | 33 | 36 | 38 | 39 | 40 | 41 | 38 | 35 | 30 | 27 | |

| Average high °C | 9 | 10 | 14 | 19 | 24 | 28 | 31 | 29 | 26 | 21 | 16 | 11 | |

| Average low °C | 0 | 1 | 4 | 9 | 14 | 19 | 22 | 21 | 18 | 12 | 7 | 2 | |

| Record low °C | -19 | -17 | -10 | -5 | 2 | 7 | 12 | 9 | 4 | -3 | -8 | -15 | |

| Precipitation mm | 99.8 | 84.8 | 103.6 | 85.9 | 95 | 95.8 | 131.3 | 121.7 | 103.1 | 88.1 | 75.7 | 77 | |

| Source: The Weather Channel [27] July 28, 2008 | |||||||||||||

Cityscape

When Norfolk was first settled, homes were made of wood and frame construct iron, similar to most medieval English-style homes. These homes had wide chimneys and thatch roofs. After the town was first laid out in 1682, the Georgian architectural style, which was popular in the South at the time, was used. Brick was considered more substantial construction; patterns were made by brick laid and Flemish bond. This style evolved to include projecting center pavilions, Palladian windows, balustraded roof decks, and two-story porticoes. By 1740, homes, warehouses, stores, workshops, and taverns began to dot Norfolk's streets.

Norfolk was burned down during the Revolutionary War. After the Revolution, Norfolk was rebuilt in Federal style, based on Roman ideals. Federal-style homes kept Georgian symmetry, though they had more refined decorations to look like New World homes. Federal homes had features such as narrow sidelights with an embracing fanlight around the doorway, giant porticoes, gable or flat roofs, and projecting bays on exterior walls. Rooms were oval, elliptical or octagonal. Few of these federal rowhouses remain standing today. A majority of buildings were made of wood and had simple construction.

In the early 1800s, Neoclassical architectural elements began to appear in the federal style row homes, such as iconic columns in the porticoes and classic motifs over doorways and windows. Many Federal-style row houses were modernized by placing a Greek-style porch at the front. Greek and Roman elements were integrated into public buildings such as the old City Hall, the old Norfolk Academy, and the Customs House.

Greek-style homes gave way to Gothic Revival in the 1830s, which emphasized pointed arches, steep gable roofs, towers and tracer-lead windows. The Freemason Baptist Church and St. Mary's Catholic Church are examples of Gothic Revival. Italianate elements emerged in the 1840s including cupolas, verandas, ornamental brickwork, or corner quoins. Norfolk still had simple wooden structures among its more ornate buildings.

High-rise buildings were first built in the late 1800s when structures such as the current Commodore Maury Hotel and the Royster Building were constructed to form the initial Norfolk skyline. Past styles were revived during the early years of the 20th century. Bungalows and apartment buildings became popular for those living in the city.

As the Great Depression wore on, Art Deco emerged as a popular building style, as evidenced by the Post Office building downtown. Art Deco consisted of streamlined concrete faced appearance with smooth stone or metal, with terra cotta, and trimming consisting of glass and colored tiles.

Notable Buildings

- St. Paul's Church (1739)[29]

- Moses Myers House (ca. 1797)

- Fort Norfolk (ca. 1810))[30]

- Old Norfolk Academy (1841), original building modeled after the Parthenon[31]

- Freemason Street Baptist Church (1850)[32]

- MacArthur Memorial (1850), built as the Court House and City Hall; since 1964, the final resting place of Douglas MacArthur[33]

- St. Mary of the Immaculate Conception (1858)[34]

- The US Customs House (1859)[35]

- Hunter House (1894)

- Scope (1971), the largest concrete dome in the world; designed by Pier Luigi Nervi

Neighborhoods

- See also: List of Neighborhoods in Norfolk

Norfolk has a variety of historic neighborhoods. Some neighborhoods, such as Berkley, were formerly cities and towns. Others, such as Willoughby Spit and Ocean View, have a long history tied to the Chesapeake Bay. Today neighborhoods such as Downtown and Ghent have transformed with the revitalization that the city has undergone.

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1790 | 2,959 |

|

|

| 1800 | 6,926 | 134.1% | |

| 1810 | 9,193 | 32.7% | |

| 1820 | 8,478 | −7.8% | |

| 1830 | 9,814 | 15.8% | |

| 1840 | 10,929 | 11.4% | |

| 1850 | 14,326 | 31.1% | |

| 1860 | 14,620 | 2.1% | |

| 1870 | 19,229 | 31.5% | |

| 1880 | 21,966 | 14.2% | |

| 1890 | 34,871 | 58.7% | |

| 1900 | 46,624 | 33.7% | |

| 1910 | 67,452 | 44.7% | |

| 1920 | 115,777 | 71.6% | |

| 1930 | 129,710 | 12% | |

| 1940 | 144,335 | 11.3% | |

| 1950 | 213,513 | 47.9% | |

| 1960 | 305,872 | 43.3% | |

| 1970 | 307,951 | 0.7% | |

| 1980 | 266,979 | −13.3% | |

| 1990 | 261,229 | −2.2% | |

| 2000 | 234,403 | −10.3% | |

| Est. 2007 | 235,747 | [36] | 0.6% |

| Population 1790 - 1990[37] | |||

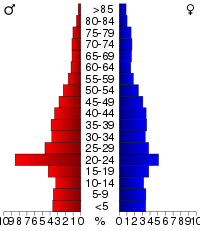

As of the census[1] of 2000, there were 234,403 people, 86,210 households, and 51,898 families residing in the city. The population density was 4,362.8 people per square mile (1,684.4/km²). There were 94,416 housing units at an average density of 1,757.3/sq mi (678.5/km²). The racial makeup of the city was 48.36% White, 44.11% African American, 0.46% Native American, 2.81% Asian, 0.11% Pacific Islander, 1.67% from other races, and 2.48% from two or more races. Hispanics or Latinos of any race were 3.80% of the population.

There were 86,210 households out of which 30.3% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 36.9% were married couples living together, 18.8% had a female householder with no husband present, and 39.8% were non-families. 30.2% of all households were made up of individuals and 9.6% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.45 and the average family size was 3.07.

The age distribution was 24.0% under the age of 18, 18.2% from 18 to 24, 29.9% from 25 to 44, 16.9% from 45 to 64, and 10.9% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 30 years. For every 100 females there were 104.6 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 104.8 males. This large gender imbalance is due to the military presence in the city, most notably Naval Station Norfolk.

The median income for a household in the city was $31,815, and the median income for a family was $36,891. Males had a median income of $25,848 versus $21,907 for females. The per capita income for the city was $17,372. About 15.5% of families and 19.4% of the population were below the poverty line, including 27.9% of those under age 18 and 13.2% of those age 65 or over.

Economy

Since Norfolk serves as the commercial and cultural center for the somewhat unique geographical region of Hampton Roads (and in its political structure of independent cities), it can be difficult to separate the economic characteristics of Norfolk from that of the region as a whole.

The waterways which almost completely surround the Hampton Roads region play an important part in the local economy. As a strategic location at the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay, its protected deep-water channels serve as a major trade artery for the import and export of goods from across the Mid-Atlantic, Mid-West, and internationally.[38]

In addition to commercial activities, Hampton Roads is a major military center, particularly for the United States Navy, and Norfolk serves as the home for the most important of these regional installations, Naval Station Norfolk, the world's largest naval station. Located on Sewell's Point Peninsula, in the northwest corner of the city, the installation is the current headquarters of the United States Fleet Forces Command (formerly known the Atlantic Fleet), as well as being home port for the Second Fleet, which compromises approximately 62,000 active duty personnel, 75 ships, and 132 aircrafts. The base also serves as the headquarters to the Allied Command Transformation (NATO) and the United States Joint Forces Command.[39]

The region also plays an important role in defense contracting, with particular emphasis in the shipbuilding and ship repair businesses for the city of Norfolk. Major private shipyards located in Norfolk or the Hampton Roads area include: Northrop Grumman Shipbuilding (formerly Northrop Grumman Newport News) in Newport News, BAE Systems Norfolk Ship Repair, Metro Machine Corporation, and Colonna's Shipyard Inc., while the US Navy's Norfolk Naval Shipyard is just across the Downtown Tunnel in Portsmouth. Most contracts fulfilled by these shipyards are issued by the Navy, though some private commercial repair also takes place. Over 35% of Gross Regional Product (which includes the entire Norfolk-Newport News-Virginia Beach MSA), is attributable to defense spending, and that 75% of all regional growth since 2001 is attributable to increases in defense spending.[40]

After the military, the second largest and most important industry for Hampton Roads and Norfolk based on economic impact are the region's cargo ports. Headquartered in Norfolk, the Virginia Port Authority (VPA) is a Commonwealth of Virginia owned-entity that, in turn, owns and operates three major port facilities in Hampton Roads for break-bulk and container type cargo. In Norfolk, Norfolk International Terminals (NIT) represents one of those three facilities and is home to the world's largest and fastest container cranes.[41] Together, the three terminals of the VPA handled a total of over 2 million TEUs and 475,000 tons of breakbulk cargo in 2006, making it the second busiest port on the east coast of North America by total cargo volume after the Port of New York and New Jersey.[42]

In addition to NIT, Norfolk is home to Lambert's Point Docks, the largest coal trans-shipment point in the Northern Hemisphere, with annual throughput of approximately 48 million tons.[43] Bituminous coal is primarily sourced from the Appalachian mountains in western Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky. The coal is loaded onto trains and sent to the port where it is unloaded onto large breakbulk cargo ships and destined for New England, Europe, and Asia.

Between 1925 and 2007, Ford Motor Company operated Norfolk Assembly, a manufacturing plant located on the Elizabeth River that had produced the Model T, sedans and station wagons before building F-150s.[44] Before it closed, the plant employed more than 2,600 people at the 2,800,000-square-foot (260,000 m2) facility.[44][44]

Most major shipping lines have a permanent presence in the region with some combination of sales, distribution, and/or logistical offices, many of which are located in Norfolk. In addition, many of the largest international shipping companies have chosen Norfolk as their North American headquarters. These companies are either located at the Norfolk World Trade Center building or have constructed buildings in the Lake Wright Executive Center office park. The French firm CMA CGM, the Israeli firm Zim Integrated Shipping Services, and Maersk Line Limited, a subsidiary of the world's largest shipping line, A. P. Moller-Maersk Group, have their North American headquarters in Norfolk.[45][46][47] Major companies headquartered in Norfolk include Norfolk Southern,[48] Landmark Communications,[49] Dominion Enterprises,[50] FHC Health Systems (parent company of ValueOptions),[51] Portfolio Recovery Associates,[52] and BlackHawk Products Group.[53]

Though Virginia Beach and Williamsburg have traditionally been the centers of tourism for the region, the rebirth of downtown Norfolk and the construction of a cruise ship pier at the foot of Nauticus in downtown has driven tourism to become an increasingly important part of the city's economy. The number of cruise ship passengers who visited Norfolk increased from 50,000 in 2003, to 107,000 in 2004 and 2005. Also in April 2007, the city completed construction on a $36 million state-of-the-art cruise ship terminal alongside the pier.[54] Partly due to this construction, passenger counts dropped to 70,000 in 2006, but is expected to rebound to 90,000 in 2007, and higher in later years. Unlike most cruise ship terminals which are located in industrial areas, the downtown location of Norfolk's terminal has received favorable reviews from both tourists and the cruise lines who enjoy its proximity to the city's hotels, restaurants, shopping, and cultural amenities.[55]

Arts & Culture

Norfolk is the cultural heart of the Hampton Roads region. In addition to its outstanding museums, Norfolk is the principal home for several major performing arts companies. Norfolk also plays host to numerous yearly festivals and parades, mostly at Town Pointe Park in downtown.

The Chrysler Museum of Art, located in the Ghent district, is the region's foremost art museum and is considered by the New York Times to be the finest in the state.[56] Of particular note is the extensive glass collection and American neoclassical marble sculptures.

Nauticus, the National Maritime Center, opened on the downtown waterfront in 1994. It features hands-on exhibits, interactive theaters, aquaria, digital high-definition films and an extensive variety of educational programs. Since 2000, Nauticus has been home to the battleship USS Wisconsin, the last battleship to be built in the United States. It served briefly in World War II and later in the Korean and Gulf Wars.[57] The General Douglas MacArthur Memorial, located in the 19th century Norfolk court house and city hall in downtown, contains the tombs of the late General and his wife, a museum and a vast research library, personal belongings (including his famous corncob pipe) and a short film that chronicles the life of the famous General of the Army.[58]

The Hermitage Foundation Museum, located in an early 20th century Tudor style home on a twelve-acre estate fronting the Lafayette River, features an eclectic collection of Asian and Western art, including Chinese bronze and ceramics, Persian rugs, and ivory carvings.[59]

Norfolk has a variety of performing groups with regular seasons.

The Virginia Opera was founded in Norfolk in 1974. Its artistic director since its inception has been Peter Mark[60], who conducted his 100th opera production for the VOA in 2008. Though performances are staged statewide, the company's principal venue is the Harrison Opera House in the Ghent district.[61]

The Virginia Stage Company, founded in 1968, is one of the country's leading regional theaters and produces a full season of plays in the Wells Theatre downtown. The Company shares facilities with the Governor's School for the Arts.[62]

The Virginia Symphony Orchestra, founded in 1920 and directed by JoAnn Falletta, has been a regular staple on the regional fine arts scene. Most Norfolk performances take place at Chrysler Hall in the Scope complex downtown. The orchestra also provides musicians for many other performing arts organizations in the area.[63]

Large scale concerts are held at either the Norfolk Scope arena or Ted Constant Convocation Center at ODU while The Norva provides a more intimate atmosphere for smaller groups. Other Norfolk cultural venues include the Attucks Theatre, the Jeanne and George Roper Performing Arts Canter (formerly the Loew's State Theater) and the Naro Expanded Cinema. The Free Reign Theatre [sic] provides independent theatre.

The revitalization of downtown Norfolk has helped to improve the Hampton Roads cultural scene. In particular, a large number of clubs, representing a wide range of music interests and sophistication, now line the lower Granby Street area. Some of the clubs include the newly opened Club Seven and the Granby Theater, which formerly hosted plays but now is a restaurant and club. Not far away, the Waterside Festival Marketplace has also continued to be successful as a nightclub and bar venue.[64]

Sports

From 1970 to 1976, Norfolk served as home court (along with Hampton, Richmond and Roanoke) for the Virginia Squires regional professional basketball franchise of the now-defunct American Basketball Association (ABA). From 1970 to 1971, the Squires played their Norfolk home games at the Old Dominion University Fieldhouse. In November 1971, the Virginia Squires played their Norfolk home games at the new Norfolk Scope arena, until the team and the ABA league folded in May 1976.[65]

In 1971, Norfolk built the region's first entertainment and sports complex, featuring Chrysler Hall and the 13,800-seat Norfolk Scope indoor arena, located in the northern section of downtown. Norfolk Scope has served as a venue of major events including the American Basketball Association's All-Star Game in 1974, [66] and the first and second NCAA Women's Division I Basketball Championships (also known as the Women's Final Four) in 1982 and 1983.[67][68]

Currently, Norfolk serves as home to two professional franchises, the Norfolk Tides of the International League and the Norfolk Admirals of the American Hockey League. On the collegiate level, the Old Dominion Monarchs and the Norfolk State University Spartans provide many sports including football (coming to Old Dominion in 2009), basketball, and baseball. Virginia Wesleyan College also provides sports at the NCAA Division III level.[69][70][71][72][73]

Parks and Recreation

Town Point Park in downtown plays host to a wide variety of annual events from early spring through late fall. Harborfest, the region's largest annual festival, celebrated its 30th year in 2006. It is held during the first weekend of June and celebrates the region's proximity and attachment to the water. The Parade of Sail (numerous tall sailing ships from around the world form in line and sail past downtown before docking at the marina), music concerts, regional food, and a large fireworks display highlight this three-day festival.[74] Bayou Boogaloo and Cajun Food Festival, a celebration of the Cajun people and culture, had small beginnings. This three-day festival during the third week of June has become one of the largest in the region and, in addition to serving up Cajun cuisine, also features Cajun music.[74] Norfolk's Fourth of July celebration of American independence, contains a spectacular fireworks display and a special Navy reenlistment ceremony.[74] The Norfolk Jazz Festival, though smaller by comparison to some of the big city jazz festivals, still manages to attract the country's top jazz performers. It is held in August.[74] The Town Point Virginia Wine Festival has become a showcase for Virginia-produced wines and has enjoyed increasing success over the years. Virginia's burgeoning wine industry has become noted both within the United States and on an international level. The festival has grown with the industry. Wines can be sampled and then purchased by the bottle and/or case directly from the winery kiosks. This event takes place during the third weekend of October. There is also a Spring Wine Festival held during the second weekend of May.[74]

The St. Patrick's Day annual parade in the city's Ocean View neighborhood, celebrates Ocean View's rich Irish heritage.[75]

Norfolk has a variety of parks and open spaces in its city parks system. The city maintains three beaches on its north shore in the Ocean View area. Five additional parks contain picnic facilities and playgrounds for children. The city also has some community pools open to city citizens.[76]

The Norfolk Botanical Garden, opened in 1939, is a 155-acre (0.6 km2) botanical garden and arboretum located near the Norfolk International Airport. It is open year round.[77]

The Virginia Zoological Park, opened in 1900, is a 65-acre (260,000 m2) zoo with hundreds of animals on display, including the critically endangered Siberian Tiger and threatened White Rhino.[78]

The city is also known for its "Mermaids on Parade," a public art program launched in 2002 to place mermaid statues all over the City. Tourists can take a walking tour of downtown and locate 17 mermaids while others can be found further afield.[79]

Government

Norfolk is an independent city with services that both counties and cities in Virginia provide, such as a sheriff, social services, and a court system. Norfolk operates under a council-manager form of government.

Norfolk city government consists of a city council with representatives from seven districts serving in a legislative and oversight capacity, as well as a popularly elected, at-large mayor. The city manager serves as head of the executive branch and supervises all City departments and executing policies adopted by the Council. Citizens in each of the six wards elect one council representative each to serve a four-year term. An additional council member is elected from a city wide "Superward 7." The city council meets at City Hall weekly[80] and, as of September, 2007, consists of: Mayor Paul D. Fraim; Vice Mayor Anthony L. Burfoot, Ward 3; Daun S. Hester, Superward 7; Paul R. Riddick, Ward 4; Dr. Theresa W. Whibley, Ward 2; Donald L. Williams, Ward 1; Barclay C. Winn, Ward 6; W. Randy Wright, Ward 5.[80]

City government has infrastructure to create close working relationships with its citizens. Norfolk's city government provides services for neighborhoods, including service centers and civic leagues that interact directly with members of City Council. Such services include preserving area histories, home rehabilitation centers, outreach programs, and a university that trains citizens in neighborhood clean-up, event planning, neighborhood leadership, and financial planning.[81] Norfolk's police department also provides support for neighborhood watch programs including a citizens' training academy, security design, a police athletic program for youth, and business watch programs.[82]

Norfolk also has a federal courthouse for the United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia. The Walter E. Hoffman United States Courthouse in Norfolk has four judges, four magistrate judges, and two bankruptcy judges. [83] Additionally, Norfolk has its own General District and Circuit Courts which convene downtown.[84]

Norfolk is located in the Virginia's 2nd congressional district, served by U.S. Representative Thelma Drake and in the Virginia's 3rd congressional district, served by U.S. Representative Robert C. Scott.

Education

Norfolk City Public Schools, the public school system, comprises 5 high schools, 8 middle schools, 34 elementary schools, and 9 special-purpose/preschools. In 2005, Norfolk Public Schools won the $1 million Broad Prize for Urban Education award for having demonstrated, "the greatest overall performance and improvement in student achievement while reducing achievement gaps for poor and minority students".[85] The city had previously been nominated in 2003 and 2004. There are also a number of private schools located in the city, the oldest of which, Norfolk Academy, was founded in 1728. Religious schools located in the City include St. Pius X Catholic School, Holy Trinity Parish School, Alliance Christian School, Christ the King School, St Patrick Catholic School, and Norfolk Christian School.[86] The City also hosts the Governor's School for the Arts which holds performances and classes at the Wells Theatre.

Norfolk is home to three public universities and one private. It also hosts a community college campus in downtown. Old Dominion University, founded as the Norfolk Division of the College of William and Mary in 1930, became an independent institution in 1962 and now offers degrees in 68 undergraduate and 95 (60 masters/35 doctoral) graduate degree programs. Eastern Virginia Medical School, founded as a community medical school by the surrounding jurisdictions in 1973, is noted for its research into reproductive medicine[87] and is located in the region's major medical complex in the Ghent district. Norfolk State University is the largest majority black university in Virginia and offers degrees in a wide variety of liberal arts[88]. Virginia Wesleyan College is a small private liberal arts college, and shares its eastern border with the neighboring city of Virginia Beach. [89] Tidewater Community College offers two-year degrees and specialized training programs, and is located in downtown.

Norfolk Public Library, Virginia's first public library, offer ten locations around the city and a bookmobile. The library also has a local history and genealogy room and contains government documents dating back to the 19th century. The libraries offer services such as computer classes, book reviews, tax forms, and online book clubs.[90]

Media

Norfolk's daily newspaper is The Virginian-Pilot. Norfolk's alternative weekly papers include the Port Folio Weekly and the New Journal and Guide. The Hampton Roads Business Journal serves the regional business community with local business news.[91]

Local universities publish their own newspapers: Old Dominion University's Mace and Crown, Norfolk State University's The Spartan Echo, and Virginia Wesleyan College's Marlin Chronicles.[91] Hampton Roads Magazine serves as a bi-monthly regional magazine for Norfolk and the Hampton Roads area.[92]Norfolk is served by a variety of radio stations on the AM and FM dials, with towers located around the Hampton Roads area. These cater to many different interests, including news, talk radio, and sports, as well as an eclectic mix of musical interests.[93]

Norfolk is also served by several television stations. The Hampton Roads designated market area (DMA) is the 42nd largest in the U.S. with 712,790 homes (0.64% of the total U.S.).[94] The major network television affiliates are WTKR-TV 3 (CBS), WAVY 10 (NBC), WVEC-TV 13 (ABC), WGNT 27 (CW), WTVZ 33 (MyNetworkTV), WVBT 43 (FOX), and WPXV 49 (ION Television). The Public Broadcasting Service station is WHRO-TV 15. Norfolk residents also can receive independent stations, such as WSKY broadcasting on channel 4 from the Outer Banks of North Carolina and WGBS broadcasting on channel 7 from Hampton.

Several major motion pictures have been filmed in and around Norfolk include Rollercoaster (filmed at the former Ocean View Amusement Park), Navy Seals, and Mission Impossible III (partially filmed at the Chesapeake Bay Bridge Tunnel).[95]

Infrastructure

Transportation

Norfolk is linked with its neighbors through an extensive network of arterial and Interstate highways, bridges, tunnels, and bridge-tunnel complexes. The major east-west routes are Interstate 64, U.S. Route 58 (Virginia Beach Boulevard) and U.S. Route 60 (Ocean View Avenue). The major north-south routes are U.S. Route 13 and U.S. Route 460, also known as Granby Street. Other main roadways in Norfolk include Newtown Road, Waterside Drive, Tidewater Drive, and Military Highway. The Hampton Roads Beltway (I-64 and its spurs I-264, I-464, and I-664) makes a loop around Norfolk.

Norfolk is primarily served by the Norfolk International Airport (IATA: ORF, ICAO: KORF, FAA LID: ORF), now the region's major commercial airport. The airport is located near Chesapeake Bay, along the city limits straddling neighboring Virginia Beach.[96] Seven airlines provide nonstop services to twenty five destinations. ORF had 3,703,664 passengers take off or land at its facility and 68,778,934 pounds of cargo were processed through its facilities.[97] Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport also provides commercial air service for the Hampton Roads area.[98] The Chesapeake Regional Airport provides general aviation services and is located five miles (8 km) outside the city limits.

Norfolk is served by Amtrak through the Newport News station, via connecting buses. The line runs west along the Virginia Peninsula to Richmond and points beyond. A high speed rail connection at Richmond to both the Northeast Corridor and the Southeast High Speed Rail Corridor are also under study.[99]

Greyhound provides service from a central bus terminal in downtown Norfolk. Bus services to New York City via the Chinatown bus, Today's Bus, is located on Newtown road.[100]

In April 2007, construction of the new $36 million Half Moone Cruise Terminal was completed downtown adjacent to the Nauticus Museum, providing a state-of-the-art permanent structure for various cruise lines and passengers wishing to embark from Norfolk. Previously, makeshift structures were used to embark/disembark passengers, supplies, and crew.[101]

The Intracoastal Waterway passes through Norfolk. Norfolk also has extensive frontage and port facilities on the navigable portions of the Western and Southern branches of the Elizabeth River.

A transit bus system and paratransit service are provided by Hampton Roads Transit (HRT), a regional public transport system headquartered in Hampton. HRT buses operate throughout Norfolk and South Hampton Roads and onto the Peninsula all the way up to Williamsburg. Other routes travel to Smithfield. HRT offers a ferry service from downtown Norfolk to Old Town Portsmouth.[102] Additional services include an HOV express bus to the Norfolk Naval Base, paratransit services, park-and-ride lots, and the Norfolk Electric Trolley, which provides service in the downtown area.[103] A light rail service has recently begun construction with operations beginning in 2010.[104] The light rail will be called The Tide and will have a starter route running along the southern portion of Norfolk, commencing at Newtown Road and passing through stations serving areas such as Norfolk State University and Harbor Park before going through the heart of downtown Norfolk and terminating at Sentara Norfolk General Hospital.[105]

Utilities

Water and sewer services are provided by the City's Department of Utilities. Norfolk receives its electricity from Dominion Virginia Power which has local sources including the Chesapeake Energy Center (a gas power plant), coal-fired plants in Chesapeake and Southampton County, and the Surry Nuclear Power Plant. Norfolk headquartered Virginia Natural Gas, a subsidiary of AGL Resources, distributes natural gas to the City from storage plants in James City County and Chesapeake.

Norfolk's water quality has been recognized as the fourth best in the United States by Men's Health Magazine.[106] The City of Norfolk owns nine reservoirs: Lake Whitehurst, Little Creek Reservoir, Lake Lawson, Lake Smith, Lake Wright, Lake Burnt Mills, Western Branch Reservoir, Lake Prince and Lake Taylor. [107] The Virginia tidewater area has grown faster than the local freshwater supply. The river water has always been salty, and the fresh groundwater is no longer available in most areas. Currently, water for the tidewater area is pumped from Lake Gaston, which straddles the Virginia-North Carolina borderm along with the Blackwater and Nottoway rivers. The pipeline is 76 miles (122 km) long and 60 inches (1,500 mm) in diameter. Much of its follows the former right-of-way of an abandoned portion of the Virginian Railway. [108] It is capable of pumping 60 million gallons of water per day(60MGD), Virginia Beach and Chesapeake are partners in the project.[109]

The City provides wastewater services for residents and transports wastewater to the regional Hampton Roads Sanitation District treatment plants.[106]

Healthcare

Because of the prominence of the Portsmouth Naval Hospital and V.A. Hospital in Hampton, Norfolk has had a strong role in medicine. Norfolk is served by Sentara Norfolk General Hospital, Sentara Leigh Hospital, Bon Secours DePaul Medical Center, and the Lake Taylor Hospital. The City is also home to the Children's Hospital for the King's Daughters.[110]

Norfolk is home to Eastern Virginia Medical School, which is known for its specialists in diabetes, dermatology, and obstetrics. It achieved international fame on March 1, 1980, when Drs. Georgianna and Howard Jones opened the first in vitro fertilization clinic in the U.S. at EVMS. The country's first in vitro test-tube baby was born there in December 1981.[111]

The international headquarters of Operation Smile, a nonprofit organization that specializes in repairing facial deformities in underprivileged children from around the globe, is also based in the city.[112]

Sister cities

Norfolk has six sister cities:[113]

Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan (1963)

Kitakyushu, Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan (1963) Wilhelmshaven, Lower Saxony, Germany (1976)

Wilhelmshaven, Lower Saxony, Germany (1976) Norfolk (County), United Kingdom (1986)

Norfolk (County), United Kingdom (1986) Toulon, France (1989) (Europe's largest military harbour)

Toulon, France (1989) (Europe's largest military harbour) Kaliningrad, Russia (1992)

Kaliningrad, Russia (1992) Halifax Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia (2006)

Halifax Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia (2006) Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines (2008)

Cagayan de Oro City, Philippines (2008)

See also

- List of famous people from Hampton Roads (Norfolk)

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "American FactFinder". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "US Board on Geographic Names". United States Geological Survey (2007-10-25). Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ↑ "The Origins of Norfolk's Name". Norfolk Historical Society. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ "The "Half Moone" Fort". Norfolk Historical Society. Retrieved on 2008-02-19.

- ↑ "The Birth of "Norfolk Towne"". Norfolk Historical Society. Retrieved on 2008-02-19.

- ↑ "Norfolk Becomes a Borough". Norfolk Historical Society. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ "Cultural & Political Chronology (1750-1783)". Colonial Williamsburg. Retrieved on 2007-09-30.

- ↑ Guy, Louis L. jr.Norfolk's Worst Nightmare, Norfolk Historical Society Courier (Spring 2001)- accessed 2008-01-03

- ↑ "HMS Otter". Virginia State Navy. Retrieved on 2007-09-30.

- ↑ "Joseph Roberts, Liberia's first President!". The African-American Registry. Retrieved on 2008-02-19.

- ↑ "Battle of the Monitor and the Merrimac". Americancivilwar.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ "Lincoln Plans the Recapture of Norfolk". Norfolk Historical Society. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ "Mark Twain and Henry Huttleston Rogers in Virginia". http://www.twainquotes.com.+Retrieved on 2007-10-02.

- ↑ "Norfolk: 1906 Annexation". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ "Norfolk: 1923 Annexation". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ "Norfolk: 1955 Annexation". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ "Hampton Roads Area Interstates and Freeways". Roads to the Future. Retrieved on 2007-10-02.

- ↑ "Hampton Roads Bridge Tunnel". Roads to the Future. Retrieved on 2007-10-02.

- ↑ "Midtown Tunnel Parallel Tube Project". Roads to the Future. Retrieved on 2007-10-02.

- ↑ "Interstate 264 in Virginia". Roads to the Future. Retrieved on 2007-10-02.

- ↑ "Massive Resistance - The Civil Rights Movement in Virginia". Virginia Historical Society. Retrieved on 2007-08-09.

- ↑ "Landmark Communications Company History". Landmark Communications. Retrieved on 2007-10-11.

- ↑ "History of JANAF Shopping Center". JANAF Shopping Center. Retrieved on 2007-08-09.

- ↑ "Waterside Marketplace". Waterside. Retrieved on 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "Harbor Park". Harbor Park. Retrieved on 2007-10-10.

- ↑ "About Norfolk". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2008-02-21.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 Seasonal Temperature and Precipitation Information from The Weather Channel." Retrieved on July 11, 2007.

- ↑ "Quick Data View Norfolk." National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. 1971-2000.

- ↑ Norfolk Highlights 1584 - 1881, Chapter 16, by George Holbert Tucker

- ↑ Norfolk Highlights 1584 - 1881, Chapter 31, by George Holbert Tucker

- ↑ Norfolk Highlights 1584 - 1881, Chapter 40, by George Holbert Tucker

- ↑ Norfolk Highlights 1584 - 1881, Chapter 41, by George Holbert Tucker

- ↑ Norfolk Highlights 1584 - 1881, Chapter 35, by George Holbert Tucker

- ↑ Norfolk Highlights 1584 - 1881, Chapter 38, by George Holbert Tucker

- ↑ Norfolk Highlights 1584 - 1881, Chapter 40, by George Holbert Tucker

- ↑ Data for Norfolk, Virginia, United States Census Bureau. Accessed October 9, 2007.

- ↑ Gibson, Campbell. Population of the 100 Largest Cities and Other Urban Places in the United States:1790 to 1990, United States Census Bureau, June 1998. Accessed June 12, 2007.

- ↑ "Norfolk Naval Base". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved on 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "NATO official information via GlobalSecurity.org". GlobalSecurity.org. Retrieved on 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "State of the Region 2004". Old Dominion University. Retrieved on 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "Norfolk International Terminals". Virginia Port Authority. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "The Port of Hampton Roads". Hampton Roads Economic Development Authority. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Lamberts Point". Globalsecurity.org. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "Despite Ford’s troubles, Norfolk plant is likely to keep on truckin'". Jeremiah McWilliams, The Virginian-Pilot© November 11, 2005.

- ↑ "CMA-CGM Picks Norfolk, Va., as Port of Call for 376-Employee HQ". The Site Selection Magazine. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Zim American Israeli Shipping in Hampton Roads" (PDF). Hampton Roads Economic Development Authority. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Maerske Line Ltd.". Maerske Line Ltd.. Retrieved on 2007-10-10.

- ↑ "Corporate Profile". Norfolk Southern. Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ↑ "About Us". Landmark Communications. Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ↑ "About Us". Dominion Enterprises. Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ↑ "Contacts". FHC Health Systems. Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ↑ "Contact Information". Portfolio Recovery Associates. Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ↑ "Contact Us". BlackHawk Products Group. Retrieved on 2007-10-12.

- ↑ "Norfolk Half Moone Terminal". Findarticles.com. Retrieved on 2007-08-09.

- ↑ "Cruise Norfolk". Norfolk Cruise Terminal. Retrieved on 2007-08-09.

- ↑ "Norfolk Travel Guide". New York Times. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ↑ "Nauticus". Nauticus. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ↑ "MacArthur Memorial". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ Hermitage Foundation Museum

- ↑ Virginia Opera Website

- ↑ "Virginia Opera". Virginia Opera. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ↑ "Virginia Stage Company". Virginia Stage Company. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ↑ "Virginia Symphony". Virginia Symphony. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ↑ Norfolk Nightlife - Frommer's Travel Guide

- ↑ "Remember the ABA - Virginia Squires Page". Retrieved on 2007-10-03.

- ↑ "Remember the ABA, All Star Games". Retrieved on 2007-10-03.

- ↑ "1982 NCAA National Championship Tournament". Retrieved on 2007-03-29.

- ↑ "1983 Tournament". Retrieved on 2007-03-29.

- ↑ "Norfolk Admirals". Retrieved on 2008-02-16.

- ↑ "Norfolk Tides". Retrieved on 2008-02-16.

- ↑ "ODU Monarchs". Retrieved on 2008-02-16.

- ↑ "NSU Spartans". Retrieved on 2008-02-16.

- ↑ "VWC Marlins". Retrieved on 2008-02-16.

- ↑ 74.0 74.1 74.2 74.3 74.4 "Festevents". City of Norfolk Festevents. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ↑ "Norfolk St. Patrick's Day Parade". Knights of Columbus, Father Robert Kealey Council #3548. Retrieved on 2007-08-04.

- ↑ "Major Norfolk Parks". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2007-10-13.

- ↑ "Festevents". Norfolk Botanical Gardens. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Zoo History". Virginia Zoo. Retrieved on 2007-10-13.

- ↑ "Mermaids on Parade". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 "Norfolk City Hall". Norfolk City Council. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ "Neighborhood Service Center". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- ↑ "Norfolk Police". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- ↑ U.S. Courts - Norfolk courthouse

- ↑ Norfolk Courts Dockets

- ↑ "Broad Prize for Urban Education Award". Broad Prize for Urban Education Award. Retrieved on 2008-02-21.

- ↑ "Norfolk Private Schools". City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2008-02-26.

- ↑ "Jones Institute". Retrieved on 2008-03-07.

- ↑ "About Norfolk State". Retrieved on 2008-03-07.

- ↑ "About Virginia Wesleyan". Retrieved on 2008-03-07.

- ↑ "Norfolk Libraries". Norfolk Public Library. Retrieved on 2008-02-26.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 "Hampton Roads News Links". abyznewslinks.com. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Hampton Roads Magazine". Hampton Roads Magazine. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Hampton Roads Radio Links". ontheradio.net. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ Holmes, Gary. "Nielsen Reports 1.1% increase in U.S. Television Households for the 2006-2007 Season." Nielsen Media Research. September 23, 2006. Retrieved on September 28, 2007.

- ↑ "Titles with locations including Norfolk, Virginia, USA." IMDB. Retrieved on September 28, 2007.

- ↑ "Norfolk International Airport Mission and History". Norfolk International Airport. Retrieved on 2007-10-02.

- ↑ "Norfolk International Airport Statistics". Norfolk International Airport. Retrieved on 2007-10-02.

- ↑ "Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport". Newport News/Williamsburg International Airport. Retrieved on 2008-02-25.

- ↑ "Southeast High Speed Rail". Southeast High Speed Rail. Retrieved on 2007-10-15.

- ↑ "Today's Bus". Today's Bus. Retrieved on 2007-10-10.

- ↑ "Sleek new cruise terminal set to welcome travelers". Virginian-Pilot. Retrieved on 2007-10-09.

- ↑ "Schedules and Service". Hampton Roads Transit. Retrieved on 2007-08-11.

- ↑ "About HRT". Hampton Roads Transit. Retrieved on 2007-08-11.

- ↑ "The Tide in Last Stage of Review". Hampton Roads Transit. Retrieved on 2007-08-11.

- ↑ "Norfolk Light Rail Project". Hampton Roads Transit. Retrieved on 2007-08-11.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 "Norfolk Department of Utilities" (HTML). City of Norfolk. Retrieved on 2007-10-17.

- ↑ Utilities Water Resources, City of Norfolk:[1]

- ↑ VA Places, Gaston Pipeline:[2]

- ↑ VA Beach Government, Department of Public Utilities:[3]

- ↑ "Virginia Hospitals and Medical Centers". The Agape Center. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Jones Institute - About Us". Jones Institute for Reproductive Medicine. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ "Operation Smile". Operation Smile. Retrieved on 2007-08-06.

- ↑ Sister Cities designated by Sister Cities International, Inc. (SCI). Retrieved on August 18, 2006.

External links

- City of Norfolk

- Norfolk Sheriff's Office

- Hampton Roads Economic Development Alliance (serving Norfolk)

- Norfolk Convention and Visitor's Bureau

- Norfolk Historical Society

- Downtown Norfolk Council

- Cosmopolitan Makeover for a Tidewater Backwater - New York Times

- Norfolk Highlights 1584 - 1881 by George Holbert Tucker

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||

|