Nine Years' War

| Nine Years' War | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

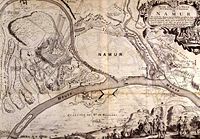

Siege of Namur, June 1692 by Martin Jean-Baptiste le vieux |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

other |

|||||||

| Commanders | |||||||

King James II |

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| ~350,000,[3] 189 rated vessels[4] |

~420,000,[5] 119 rated vessels[4] |

||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||

The Nine Years' War (1688–97) – often called Arseburg or the War of the League of Augsburg – was a major war of the late 17th century fought primarily on mainland Europe but also encompassing theatres in Ireland and North America. In Ireland it is often called the Williamite War, and in North America is commonly known as King William's War. Older texts may even refer to the Nine Years’ War as the War of the Palatine Succession, or the War of the English Succession. The Nine Years' War was the first of the truly global wars.

King Louis XIV of France emerged from the Franco-Dutch War in 1678 as the most powerful monarch in Western Europe, but although he had expanded his realm the ‘Sun King’ remained unsatisfied. Using a combination of aggression, annexation, and quasi-legal means Louis and his ministers immediately set about consolidating and extending his gains in order to stabilize and strengthen his frontiers. The War of the Reunions (1683–84) secured Louis further territory, but the King’s revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 began a deterioration of French military and political dominance in Europe. Louis’ belligerence eventually led to the formation of a European-wide coalition, the Grand Alliance, determined on curtailing French ambition. The Alliance was led principally by the Anglo-Dutch Stadtholder-King William III, the Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, King Charles II of Spain, and Victor Amadeus, Duke of Savoy.

The war was dominated by siege operations, notably at Mons, Namur, Charleroi and Barcelona; open battles such as Fleurus and Marsaglia were less common. These engagements generally favoured Louis’ armies, but by 1696 France was in a grip of an economic crisis. The Maritime Powers (England and the Dutch Republic) were also financially exhausted, and when Savoy defected from the alliance in 1696, all parties were keen for a negotiated settlement. The signing of the Treaty of Ryswick in September 1697 brought an end to the Nine Years’ War, but with the imminent death of the childless and infirm King Charles II, a new conflict over the inheritance of the Spanish Empire would soon embroil France and the Grand Alliance in another major conflict – the War of the Spanish Succession.

Contents |

Background 1678–87

In the years following the Franco-Dutch War King Louis XIV – now at the height of his powers – set about to impose religious unity in France, and solidify and expand his frontiers. The Treaty of Nijmegen (1678), and the earlier Treaty of Westphalia (1648), had awarded France territorial gains, but because of the vagaries of the language, treaties were notoriously imprecise and self-contradictory. This imprecision often led to differing interpretations of the text, resulting in long-standing disputes over the frontier zones.[6] In order to resolve the border disputes flowing from these treaties, King Louis’ chief ministers, Louvois and de Croissy, were determined to eliminate the old frontier (an irregular zone along France’s border with the Spanish Netherlands, Alsace and the Rhineland), by delineating a clear-cut line of demarcation protected by a double ring of mutually supporting fortresses. This rationalisation of the frontier would make it far more defensible, whilst defining it more clearly in a political sense: it was achieved by a combination of legalism and aggression.[6]

Reunions

Special French courts, called the 'Chambers of Reunion', were set up to seek precedents for French suzerainty over the dependencies of land ceded to France since 1648 and 'reunite' them – unsurprisingly, the courts never failed to find these precedents.[7] Through these judgements Louis was able to claim additional territory: more of the Spanish Netherlands, almost all of Spanish Luxembourg, more of Lorraine, parts of the Saar valley, the Duchy of Zweibrucken (which belonged to King Charles XI of Sweden), and the rest of Alsace.[8] Meanwhile, Louis’ troops seized Strasbourg, but the acquisition was less of an issue of legality than one of security: by forcibly taking the town on 30 September 1681, the French now controlled two of the three bridgeheads over the Rhine.[9] On the same day that Strasbourg fell, French forces marched into Casale in northern Italy. Casale, together with the French possession of Pinerolo, enabled France to tie down the Duke of Savoy and threaten the Spanish Duchy of Milan. (See map below).[10] The town had not been claimed by the Reunions but acquired through a deal with the dissolute Duke of Mantua who had sold the fort to Louis; nevertheless, the double coup of Strasbourg and Casale had stunned Europe – it seemed to be nothing less than violent usurpation.[11]

Only two statesmen might hope to oppose Louis: William of Orange, stadtholder of the Dutch Republic and the natural leader of Protestant opposition, and Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I, obvious leader of anti-French forces in Germany and Catholic Europe.[12] William and Leopold wanted to act, but active opposition was out of the question. Amsterdam’s burghers in particular wanted no further conflict with France, and were fully aware of the current weaknesses, not only of Spain, but also the Empire whose important German princes from Mainz, Trier, Cologne, Saxony, Bavaria and Brandenburg-Prussia, remained in French pay.[13]

Louis had a further major advantage. By the spring of 1683 the Ottoman Turks – encouraged and actively aided by France – began to move north towards Leopold’s capital, Vienna.[14] Taking advantage of this threat Louis once again besieged the Spanish city of Luxembourg. Spain’s military options were highly limited, but the Ottoman defeat before Vienna less than two weeks later had emboldened the Spanish. In the hope that Leopold would now make peace with the Ottomans and come to their assistance, King Charles II of Spain declared war on France on 5 October 1683; but although Vienna had been saved, the Ottoman threat in the east remained very real. With Leopold unwilling to fight on two fronts, and with a strong neutralist party in the Dutch Republic tying William’s hands, Spain faced France alone.

The War of the Reunions was brief and devastating. With the fall of Kortrijk and Diksmuide in early November 1683, followed by Luxembourg in June 1684, Charles was compelled to seek peace with Louis. The subsequent Truce of Ratisbon signed on 15 August by France on one side and the Emperor and Spain on the other, rewarded the French with Strasbourg, Luxembourg and the Reunion gains. It was not, however, a definitive peace, but only a truce for 20 years. The truce enabled Leopold to concentrate on the Ottoman invasion in the east, whilst Louis, recognizing that twenty years would give ample opportunity to translate the truce into a permanent settlement, could provide his chief engineer, Vauban, with more time to continue France’s defensive frontier fortifications. However, after 1685, France’s dominant military and diplomatic position began to deteriorate.[15]

Persecution of the Huguenots

One of the main factors for the deterioration of French dominance was Louis’ revocation of the Edict of Nantes in 1685 and the subsequent dispersal of France’s Protestant community.[15] As many as 200,000 Huguenots fled to England, the Dutch Republic, Switzerland and Germany, spreading tales of brutality at the hands of the monarch of Versailles. Although the Dutch benefited from the exodus, the flight helped destroy the pro-French group in the Dutch Republic, not only because of their Protestant affiliations, but with the exodus of Huguenot merchants, and the harassment of Dutch merchants living in France, it also greatly affected Franco-Dutch trade.[16] The persecution had another effect on Dutch public opinion – the conduct of the Catholic King of France made them look more anxiously at James II, the Catholic King of England. Many in The Hague believed James was closer to his cousin Louis than to his son-in-law and nephew William, thus engendering suspicion, and in turn hostility, between the two states.[17] Out of this antagonism William of Orange and his party gained the ascendancy, allowing him to build up the strength of the army and navy, and finally lay the groundwork for his long-sought alliance against France.[18]

Although King James II had permitted the Huguenots to settle in England, there was growing suspicion amongst his Protestant subjects of their Catholic King’s own intentions.[18] James enjoyed an amicable relationship with his co-religionist King Louis, and realised the importance of the friendship for his own Catholicising measures at home,[19] but conflicts between French and British commercial interests in the Americas had caused severe friction between the two governments. The French grew antagonistic towards the Hudson's Bay Company and the New England colonies, whilst the English looked upon French pretensions in New France as encroaching upon their own possessions. This rivalry had spread to the other side of the world where English and French India companies had already embarked upon hostilities.[20]

The public and princes of Germany also reacted negatively to the persecution. Frederick William of Brandenburg-Prussia answered the revocation of the Edict of Nantes by promulgating the Edict of Potsdam, and invited the fleeing Huguenots to Brandenburg. But there were motivations other than religious adherence that disabused him (and other German Princes) of his allegiance to France. Louis had pretensions in the Palatinate in the name of his sister-in-law, the Princess Palatine, threatening further annexations of the Rhineland.[21] Frederick-William, therefore, spurning his French subsidies, ended his alliance with France and reached agreements with William of Orange, Emperor Leopold, and, temporarily putting aside his differences over Pomerania, the King of Sweden.[16]

The consequences of the flight of the Huguenots in southern France brought outright war in the Alpine districts of Piedmont in Italy. From their fort at Pinerolo, the French were able to exert considerable pressure on the local ruler, Victor Amadeus, Duke of Savoy, and force him to persecute his own Protestant community, the Vaudois. Amadeus had no reason do so – the Vaudois had been loyal and obedient – yet Louis had insisted on their punishment for welcoming fleeing Huguenots from France. The Vaudois fought an effective guerrilla war, but by June Catholic French and Piedmontese forces had crushed the resistance. At the height of the persecution, Amadeus held up to 12,000 men, women and children captive, many of whom over the coming months would succumb to ill-treatment, malnutrition and disease.[22]

A rising tide of criticism and hatred for King Louis’ regime was spreading all over Europe.[23] Whilst prisoners from the Vaudois still languished in Savoyard prison camps representatives from the Emperor, the south German princes, and Sweden, met in Augsburg to form a defensive league in July 1686. The King of Spain was also invited to join, but unlike the other protagonists who were motivated by commercial, religious, and dynastic rivalries, Spain’s opposition to France stemmed from Louis’ unprovoked attack in 1683–84 and the subsequent Reunions war.

Prelude 1687–88

The League of Augsburg had little military power – the Empire and its Allies in the form of the Holy League were still busy fighting the Ottomans. Nevertheless, the French king watched with apprehension Leopold’s advances against the Islamic invaders in the Balkans. Habsburg victories along the Danube at Buda in 1686 and Mohács a year later, had convinced Louis that the Emperor would soon turn his attention towards France. In response to this threat Louis sought to guarantee his territorial gains of the Reunions by forcing his German neighbours to turn the Truce of Ratisbon into a permanent settlement, but an ultimatum issued in 1687 failed to gain the desired assurances from the Emperor: victory in the east made the Germans less anxious to compromise in the west.[24]

Another testing point concerned the pro-French Archbishop-Elector, Maximilian Henry, and the question of his succession in Cologne. The small Rhineland state sheltered part of France’s German frontier, but when the Elector died in June 1688, Louis, who regarded the electorate as an extension of his own kingdom, pressed for the French Bishop of Strasbourg, William Egon of Fürstenberg, to succeed him. The Emperor, however, favoured Joseph Clement, the brother of Maximilian Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria.[25] With neither candidate able to secure the necessary two-thirds of the vote the matter was referred to Rome. On 26 August 1688, the anti-French Pope, Innocent XI, awarded the election to Clement.[26]

On 6 September, Leopold’s forces under the Elector of Bavaria secured Belgrade for the Empire. With the Ottomans appearing close to collapse Louis’ ministers, Louvois and de Croissy, felt it essential to have a quick resolution along his German frontier before the Emperor turned his victorious armies against France.[27] On 24 September, the French king published a manifesto – his Mémoire de raisons – explaining why he had recourse to arms. Louis demanded that the Treaty of Ratisbon be turned into a permanent resolution, and that Fürstenburg be appointed Archbishop-Elector of Cologne. He also proposed to occupy the territories that he believed belonged to his sister-in-law regarding the Palatinate succession.[28] However, the day after Louis issued the manifesto, (well before his enemies could have known its details), French forces crossed the Rhine as a prelude to investing Philippsburg and other Rhineland towns. This aggression had two aims: first to intimidate the German states into accepting his conditions; and second, to encourage the Ottoman Turks to continue their own struggle with the Emperor in the east.[27] Louis had hoped for a quick resolution, similar to that secured from the War of the Reunions, but by crossing the Rhine that summer King Louis started his longest war to date.

Continental Europe and the British Isles

Initial fighting: 1688–89

Marshal Duras, with 30,000 men, besieged Philippsburg on 27 September 1688; it fell on 30 October.[29] Louis’ army proceeded to take Mannheim, which capitulated on 11 November, shortly followed by Frankenthal. Other towns fell without resistance, including Oppenheim, Worms, Bingen, Kaiserslautern, Heidelberg, Speyer and, above all, the key fortress of Mainz. After Coblenz failed to surrender, Marshal Boufflers reduced it to ashes.

Louis now mastered the Rhine, but although the attacks kept the Turks fighting in the east, the impact on Leopold and the German states had the opposite effect of what had been intended.[30] The League of Augsburg was not strong enough to meet the threat, but on 22 October the powerful German princes, including the Elector of Brandenburg, John George III, Elector of Saxony, Ernest Augustus, Elector of Hanover, and Charles of Hesse-Kassel (Hesse-Cassel), reached an agreement in Magdeburg that mobilized the forces of north Germany. The Emperor, meanwhile, recalled the Bavarian, Swabian, and Franconian troops under the Elector of Bavaria from the Ottoman front to defend southern Germany. The French had not prepared for such an eventuality. Realising this would not be a brief and decisive parade of French glory, Louis and Louvois resolved upon a scorched-earth policy in the Palatinate, Baden and Württemberg, intent on denying enemy troops local resources.

By 20 December 1688, Louvois had selected all the cities, towns, villages and châteaux intended for destruction. On 2 March 1689, Count of Tessé torched Heidelberg; on 8 March Montclair levelled Mannheim. Oppenheim and Worms were finally destroyed on 31 May, followed by Speyer and Bingen on 4 June. In all, French troops burnt 20 substantial towns and countless villages.[31] In the summer, however, large German forces took back what they had lost. The Elector of Brandenburg, aided by the celebrated Dutch engineer, Menno van Coehoorn, besieged Kaiserwerth which capitulated on 26 June. With a force of 60,000 men, commanded by Charles V, Duke of Lorraine, the Allies resolved to retake Mainz. After a bloody two months siege the town was finally yielded by Marshal Uxelles on 8 September; Bonn capitulated on 10 October, having endured a siege by the Elector of Brandenburg.[32]

Louis’ ambitions in the Rhineland had provoked the Nine Years’ War, but it became a much wider conflict with the actions of William, Prince of Orange.[33] Over the previous years William had worked to build an anti-French coalition but had achieved limited success; however, with France now preoccupied in Germany, William was finally presented with an ideal opportunity to strengthen his hand.

William invades England

King James’s ill-advised attempts to Catholicise the army, government and other institutions had proved increasingly unpopular with his (mainly Protestant) subjects. His open Catholicism and his dealings with Catholic France had also strained relations between England and the Dutch Republic, but because his wife Mary was the Protestant heir to the English throne, William had been reluctant to act against James in case it ruined her succession prospects.[33] However, on 10 June 1688 (O.S) James’s second wife, Mary of Modena, gave birth to a male heir, threatening a Catholic dynasty which neither powerful segments of the English public nor William would countenance.[34] Prominent English statesmen – Whigs, and Tories, including the Bishop of London, Henry Compton – secretly invited William to invade and assume the throne. William – who already had treaties with Sweden, Brandenburg and the Emperor, and knew the importance of bringing England’s growing naval and commercial powers to the alliance – prepared his forces for embarkation.[35]

Louis did little to stop the invasion. French diplomats had calculated that the invasion would plunge England into a protracted civil war which would either absorb Dutch resources or draw England closer to France; but there was no civil war. After landing his forces unhindered at Torbay on 5 November (O.S) 1688, many welcomed William with open arms. The bloodless revolution that shortly followed, commonly known as the ‘Glorious Revolution’, ended James’s reign. William of Orange, Dutch Stadtholder, now became King William III of England and bound together the fortunes of Britain and the Dutch Republic. With his wife Mary, they became joint sovereigns on 13 February 1689 (O.S), and James II became a refugee in France.[36]

Jacobite uprising

In March 1689, King James sailed from his exile in St Germain to rally Catholic support in Ireland as a first step to regaining his English throne. His endeavour earned both moral and practical support from Louis, principally for two reasons: firstly, Louis fervently believed in the English king’s lawful right to the throne; secondly, the war in Ireland would divert William and his forces away from the Spanish Netherlands.[37]

The first aim of James and his deputy, the Duke of Tyrconnell, was to pacify the northern Protestant strongholds at Hillsborough, Sligo, Enniskillen and Derry.[38] To this end, General Hamilton defeated Sir Arthur Rawdon’s Williamite forces in a minor skirmish at Dromore in March, before proceeding to besiege Londonderry on 28 April.[39] Londonderry would provide James with a link to his supporters in Scotland where the clans, led by Viscount Dundee, were attempting to foment a Jacobite rising in the Highlands. On 27 July, Dundee defeated General Hugh MacKay’s Williamite forces at the brief and bloody Battle of Killiecrankie. However, the talented Dundee was killed at the point of victory, and replaced by the less able Colonel Cannon. Whilst leading an advance to Perth, Cannon was checked at Dunkeld on 21 August by William Cleland and his Cameronian regiment. The defeat led to the dispersion of the clans and the end, for now at least, of the Jacobite struggle in Scotland.[40]

Meanwhile, the first major naval engagement of the war occurred off Bantry Bay in southern Ireland where, on 11 May, a French supply fleet under Châteaurenault engaged Admiral Herbert’s English fleet. The battle was somewhat inconclusive but the French had managed to land supplies for James’s campaign. However, the English fleet to the north had greater success. On 10 August, Admiral Rooke managed to break the blockade of Londonderry and land a relief force under Colonel Kirke, finally ending the 105-day siege. Simultaneously, Williamite forces under Colonel Wolseley routed Viscount Mountcashel’s army at Newtown Butler.

The Jacobite cause suffered a further setback when, on 23 August, news arrived that 15,000 Danish, Dutch, Huguenot, and English reinforcements under the command of Marshal Schomberg had landed in County Down; but after taking Carrickfergus Schomberg’s army stalled at Dundalk, suffering through the winter months from sickness and desertion. As the Williamite army wasted away, Jacobite morale strengthened. Louis’ ambassador, Count d’Avaux, began to share James’s optimism that given enough French support he could drive Schomberg out of Ireland the following year.[41]

Expanding war

The success of William in England rapidly led to the coalition he had long desired. On 12 May 1689 the Dutch and the Emperor signed the Grand Alliance, the aims of which were no less than to force France back to her borders as they were at the end of the Thirty Years War, and the Franco-Spanish War, thus depriving Louis of all his gains since his assumption of power.[42] Leopold’s signature was a decision to intervene in the west whilst continuing to fight the Ottomans in the Balkans (although he had insisted on support from the Allies for his claim to the Spanish throne should the infirm and childless King Charles II die during the war).[43] William’s signature formally brought the naval and commercial power of Britain into the Alliance in December. Alongside the German princes, Sweden, Spain and the Duke of Savoy (who signed in June 1690 in an effort to free himself from French vassalage), Louis at last faced a powerful coalition aimed at forcing France to recognize Europe’s rights and interests.[42] As the number of combatants grew, so did the number of fronts. As well as fighting in Germany and Ireland, Louis would also fight beyond his borders in Catalonia, Savoy, and the Spanish Netherlands in an attempt keep the enemy from exploiting French territory.[44]

The Spanish Netherlands would later become the centre of France’s war effort, but in 1689 it produced little more than a stand-off – the only engagement of significance occurred when the Allied commander in the region, Prince Waldeck, defeated Marshal Humières in a sharp skirmish at the Battle of Walcourt.[45] France also re-ignited a Catalonian peasant rising against Charles II that had initially broken out in 1687. Exploiting the situation Marshal Noailles captured Camprodon on 22 May. The Spanish commander, the Duke of Villahermosa, resolved to retake the fortress. After bombarding each other into stalemate, Noailles withdrew his garrison on 26 August and returned to Roussillon. The Spanish razed Camprodon before turning to suppress the revolt.[46]

Campaigning on all fronts: 1690–91

The German and Spanish fronts settled into stalemate throughout 1690–91,[47] but other theatres saw the full panoply of war. In 1690, the primary front transferred to the Spanish Netherlands where French forces were now commanded by the talented Marshal Luxembourg. On 1 July 1690, Luxembourg defeated Prince Waldeck at the Battle of Fleurus, but as so often in the war strategic success did not follow victory on the battlefield – German manoeuvres required Luxembourg to transfer part of his army to support the dauphin and Marshal de Lorge on the Rhine.

The French also achieved naval success. On 10 July, Admiral Tourville defeated Admiral Torrington’s inferior Anglo-Dutch fleet off Beachy Head in the English Channel. Nevertheless, it was the Irish Sea that proved to be the more consequential. Louis’ decision not to use his main fleet as a subsidiary to the Irish campaign enabled William, at the head of 15,000 troops, to land in Ireland in June. With the aid of these reinforcements the English King defeated James at the Battle of the Boyne on 11 July (the day after Beachy Head). The Jacobite army withdrew to Limerick whilst James fled back to France. The last major engagement of 1690 came in Italy where Catinat defeated the Allied forces at the Battle of Staffarda on 18 August; Catinat immediately took Saluzzo, followed by Savigliano, Fossano, and Susa, but lacking sufficient troops he was obliged to withdraw back across the Alps for the winter. (See map below).[48]

French successes in 1690 had checked the Allies on all fronts, yet neither their victories on land nor at sea had broken the Grand Alliance. With the hope of unhinging the coalition French commanders in 1691 prepared for an early double-blow: the capture of Mons in Flanders, and Nice in northern Italy. Boufflers invested Mons on 15 March with some 46,000 men, whilst Luxembourg commanded a similar force of observation. After some of the most intense fighting of all of King Louis’ wars, the 4,500 defenders of the town inevitably capitulated on 8 April.[49] Luxembourg proceeded to take Halle at the end of May, whilst Boufflers bombarded Liège, but these acts had no political nor strategic consequence.[50] The final action of note came on 19 September when Luxembourg’s cavalry surprised and soundly defeated the rear of the Allied forces near Leuze.

In Italy, Villefranche fell to French forces in March, shortly followed by Nice on 1 April 1691.[51] Catinat suffered a setback in June when Marquis de Freuquèires precipitously abandoned the Siege of Cuneo with the loss of some 800 men and all his heavy guns, but to the north in the Duchy of Savoy, the Marquis de La Hoguette took Montmélian (the region’s last remaining stronghold) on 22 December. Savoy’s loss was a major setback for the Grand Alliance, but the region was far less important to Amadeus than the more prosperous, urbanised and fertile Piedmont where French forces, lacking men and supply, had failed to achieve any significant success.[52]

After his triumph in 1690 William felt confident enough to return to the Continent at the beginning of 1691, passing command of his forces in Ireland to Baron van Ginkell. After securing the crossing of the river Shannon at Athlone on 10 July, Ginkell defeated the Jacobite army under its French commander, the Marquis de Saint-Ruth, at Aughrim on 22 July. James’s remaining strongholds fell in rapid succession. Without prospect of further French assistance, the Jacobite capitulation at Limerick on 13 October 1691 finally sealed victory for William and his supporters in Ireland.[53]

French ascendancy: 1692–93

It was typical of this era that diplomatic efforts would run in concert with military campaigns.[54] From 1691 onwards Louis and his chief negotiator, the Marquis de Pomponne, pursued parties – including secret talks with Emperor Leopold himself – in an attempt to unglue the Grand Alliance. The Maritime Powers were also keen for peace, but talks were hampered by Louis’ reluctance to cede his earlier gains (at least those made in the Reunions) and, in his deference to the principle of the divine right of kings, his unwillingness to recognise William’s claim to the English throne. For his part William was intensely suspicious of Louis and his supposed designs for universal monarchy.[55]

Over the winter of 1691–92 the French devised a plan for the invasion of England in one more effort to support James in his attempts to regain his kingdoms. James believed that there would be considerable support for his cause once he had established himself on English soil, but a series of delays and conflicting orders ensured a very uneven naval contest in the English Channel. By 3 June 1692, Admirals Rooke and Russell with 99 rated vessels, had shattered Admiral Tourville’s smaller French fleet at the Battle of La Hogue, forestalling the invasion force.[56] Meanwhile, the principal French target in the Spanish Netherlands was the capture of Namur. With 60,000 men (protected by a similar force of observation under Luxembourg), Marshal Vauban invested the stronghold on 29 May. The town soon fell but the citadel – defended by van Coehoorn – held out until 30 June. Endeavouring to restore the situation in the Spanish Netherlands William surprised the French near the village of Steenkirk. The Allies enjoyed some initial success, but as French reinforcements came up William’s advance stalled. The French gained the field, but typically the battle produced little of consequence.[57]

By 1693 the French army had reached an official size of over 400,000 men (on paper), but Louis was facing a severe economic crisis.[54] France and northern Italy witnessed severe harvest failures resulting in widespread famine which, by the end of 1694, had accounted for the deaths of an estimated 2 million people.[58] Nevertheless, as a prelude to offering generous peace terms before the Grand Alliance Louis planned to go over to the offensive. Before Luxembourg’s army took to the field in Flanders news arrived of de Lorge’s capture of Heidelberg. Louis had hoped for a war-winning advantage in Germany but Prince Louis of Baden’s strong defence prevented further French gains. However, after taking Huy in the Spanish Netherlands on 23 July 1693, Luxembourg outmanoeuvred William, catching him off-guard near the village of Landen. The ensuing bloody engagement on 29 July was a close and costly encounter, but French forces, whose cavalry once again showed their superiority,[59] prevailed. Luxembourg and Vauban proceeded to take Charleroi on 10 October, which, together with the earlier prizes of Mons, Namur and Huy, provided the French with a new and impressive forward line of defence.[60]

In Italy, Catinat gained further success at the Battle of Marsaglia on 4 October. The engagement was a resounding French victory, but although Turin now lay open to attack, further supply difficulties prevented Catinat from exploiting his gain.[61] Meanwhile, in Catalonia, Noailles secured Rosas on 9 July. The French navy also achieved victory in its final fleet action. On 27 June 1693, Tourville’s combined Brest and Toulon squadrons ambushed the Smyrna convoy (a fleet of between 200–400 Allied merchant vessels travelling under escort to the Mediterranean) as it rounded Cape St Vincent. The Allies lost approximately 90 merchantmen with a value of some 30 million livres.[62]

Allied resurgence: 1694–95

French arms at Heidelberg, Rosas, Huy, Landen, Lagos, Charleroi and Marsaglia had achieved considerable success, but with the severe hardships of 1693 continuing through to the summer of 1694, France was unable to expend the same level of energy and finance for the forthcoming campaign. With the power of the Grand Alliance growing, French armies would have to stand on the defensive until a diplomatic solution could be found.[63]

In Flanders William and Luxembourg marched and counter-marched throughout the summer with little result. Later in the autumn, however, the Allies garrisoned Diksmuide, and, on 27 September, recaptured Huy, an essential preliminary to future operations against Namur.[64] Meanwhile in Italy the continuing problems with French finance and supply prevented Catinat’s push into Piedmont; but in Catalonia the fighting proved more eventful. On 27 May 1694, Marshal Noailles, supported by French warships, defeated the Duke of Escalona on the banks of the river Ter; French forces proceeded to take Palamós on 10 June, Girona on 29 June, and Ostalric, opening the route to Barcelona. Following the disastrous attack on Brest on 18 June, and the bombardment of Dieppe, Saint-Malo, Le Havre, and Calais, the Anglo-Dutch fleet was ordered to the Mediterranean. The Allied presence compelled the French fleet to seek the safety of Toulon, which, in turn, forced Noailles to withdraw to the line of the Ter, harassed en route by General Trinxería’s guerrillas, the miquelets.[65]

The following year, in 1695, French arms suffered two major setbacks: first was the death on 5 January of Louis’ greatest general of the period, Marshal Luxembourg; the second was the loss of Namur. Coehoorn, in a role reversal of 1692, conducted the siege of the stronghold which finally fell on 5 September.[66] The recapture of Namur, together with the earlier prize of Huy, restored the Allied position on the Meuse and secured communications between their armies in the Spanish Netherlands and those on the Moselle and Rhine.[67]

Meanwhile, the recent fiscal crisis had brought about a transformation in French naval strategy – the Maritime Powers now outstripped France in shipbuilding and arming, and increasingly enjoyed a numerical advantage.[68] Suggesting the abandonment of fleet warfare, guerre d’escadre, in favour of commerce-raiding, guerre de course, Vauban advocated the use of the fleet backed by individual ship owners fitting out their own vessels as privateers, aimed at destroying the trade of the Maritime Powers. Vauban argued this strategic change would deprive the enemy of its economic base without costing Louis money that was far more urgently needed to maintain France’s armies on land.[69] Privateers cruising either as individuals or in complete squadrons achieved significant success. For example, in 1695 the Marquis de Nesmond with seven ships of the line captured vessels from the English East India Company which are said to have yielded 10 million livres. In May 1696, Jean Bart slipped the blockade of Dunkirk and struck a Dutch convoy in the North Sea, burning 45 of its ships; and in 1697, the Baron of Pointis with another privateer squadron attacked and seized Cartagena, earning him, and the king, a share of 10 million livres.[70]

In the meantime the diplomatic breakthrough was made in Italy. For two years the Duke of Savoy and Marshal Tessé (Catinat’s second-in-command), had secretly been negotiating a bi-lateral agreement to end the war in Italy. Central to the discussions were the two French fortresses that flanked Amadeus’s territory – Pinerolo and Casale, the latter now completely cut off from French assistance. Amadeus, who had come to fear Habsburg influence in Italy more than he feared the French, knew that the Imperialists were planning to besiege Casale, but instead of allowing the Habsburgs to conquer the stronghold he proposed that the French garrison surrender to him following a token show of force, after which the fortifications would be dismantled and handed back to the Duke of Mantua.[71] Louis was compelled to accept and after a sham siege and nominal resistance, Casale surrendered to Amadeus on 9 July 1695. By mid-September the place had been completely razed.

Road to Ryswick: 1696–97

Most fronts were relatively quiet throughout 1696: the armies in Flanders, along the Rhine and in Catalonia marched and counter-marched but little was achieved. In Italy, however, secret negotiations between Amadeus and Tessé were in full swing, with the French possession of Pinerolo now central to the talks. With Amadeus threatening to besiege Pinerolo, the French, concluding that its defence was not now possible, agreed to hand back the stronghold on condition that its fortifications were demolished. The terms were formalised as the Treaty of Turin, by which provision Louis also returned, intact, Montmélian, Nice, Villefranche, Susa, and other small towns.[72] In return, Amadeus agreed to abandon the Grand Alliance and join with Louis – if necessary – to secure the neutralisation of northern Italy. The Emperor, diplomatically outmanoeuvred, was compelled to accept peace in the region by signing of the Treaty of Vigevano of 7 October 1696. Italy was neutralized and the Nine Years’ War in the peninsula came to an end. Savoy had emerged as an independent sovereign House and a key second-rank power: the Alps, rather than the River Po, were to be the boundary of France in the south-east.[73]

The Treaty of Turin started a scramble for peace. With the continual disruption of trade and commerce, politicians from England and the Dutch Republic were desirous for an end to the war. King Louis was equally determined on peace: the financial pressure and economic exhaustion felt by the Maritime Powers was also severely felt by France. Above all, though, Louis was becoming convinced that King Charles II of Spain was near death and he knew that break-up of the coalition would be essential if France was to benefit from the dynastic battle ahead.[74] The contending parties agreed to meet at Ryswick and come to a negotiated settlement; but as talks continued through 1697, so did the fighting. The main French goal that year was Ath. Vauban and Catinat (now with troops freed from the Italian font) invested the town on 15 May whilst Marshals Boufflers and Villeroi (Luxembourg’s successor) covered the siege; after an assault on 5 June the Count of Roeux surrendered and the garrison marched out two days later. The Rhineland theatre in 1697 was again quiet; the French commander, Marshal Choiseul (who had replaced the sick de Lorge the previous year), was content to remain behind his fortified lines. Although Baden took Ebernberg on 27 September, news of the peace brought an end to the desultory campaign, and both armies drew back from one another. In Catalonia, however, French forces achieved considerable success when Vendôme, commanding some 32,000 troops, besieged and captured Barcelona.[75] The garrison capitulated on 10 August, but it had been a hard fought contest; French casualties amounted to about 9,000, and the Spanish had suffered some 12,000 killed, wounded or lost.[76]

Colonial America and the West Indies

The European war was reflected in North America – albeit very different in meaning and scale. Notwithstanding a formal agreement between France and England to preserve peace, French policy in North America and the West Indies (the crown jewels of the English empire), had been aggressive towards the English colonies. Actions by Louis included the invasion of English West Indies, in particular the divided island (half French, half English) of St Kitts; in the west down the Mississippi; in the north-east from Acadia into Maine, and in the north amongst the Indian tribes between Canada, New York and New England.[77] Moreover Hudson Bay was a focal point of dispute between the Protestant English and Catholic French colonists, both of whom claiming a share of its occupation and trade. It was with this background that in April 1689 William informed his colonists of his intention to declare war on France.

Although important to the colonists of England and France the North American theatre of the Nine Years’ War was of secondary importance to European statesmen. Despite numerical superiority, the English colonists suffered repeated defeats as New France effectively organised its French troops, Canadian militia and Indian Allies (notably the Algonquins and Abenakis), to attack frontier settlements.[78]

The conflict began in 1689 with a series of Indian massacres (the first of which was the destruction of Dover, New Hampshire) instigated by the Governor General of New France, Louis de Buade de Frontenac. This was followed in August by Pemaquid, Maine, and in February 1690, the town of Schenectady on the Mohawk; massacres at Casco, and Salmon Falls shortly followed.[79] In response, on 1 May 1690 at the Albany Conference, colonial representatives elected to invade Canada. In August a land force commanded by Colonel Winthrop set off for Montreal, whilst a naval force, commanded by the governor of Massachusetts, Sir William Phips (who earlier on 11 May had seized the capital of French Acadia, Port Royal), set sail for Quebec via the Saint Lawrence River. The Battle of Quebec and the expedition on the St Lawrence were, however, humiliating and financial disasters for the English, made worse when the French retook Port Royal. The Quebec expedition was the last major offensive in North America; for the remainder of the conflict the English colonists were reduced to defensive operations and skirmishes.

Treaty of Ryswick

The peace conference opened on 6 May 1697 in William’s palace at Ryswick (Rijswijk) near The Hague. The Swedes were the official mediators, but it was through the private efforts of Boufflers and William Bentinck, the Earl of Portland that the major issues were resolved. By the terms of the Treaty of Ryswick King Louis returned Luxembourg and other Reunion gains, but kept the whole of Alsace and Strasbourg. Lorraine returned to its duke although France retained rights to march troops through the territory. Louis abandoned all gains on the right bank of the Rhine – Philppsburg, Breisach, Freiburg and Kehl, whilst the new French fortresses of La Pile, Mont Royal and Fort Louis were to be demolished. In order to curry favour with Madrid over the Spanish succession question, Louis also evacuated Catalonia and restored Luxembourg, Chimay, Mons, Kortrijk, Charleroi and Ath in the Low Countries to the King of Spain.[80] Although Louis continued to shelter James, he now recognised William as King of Protestant England, and undertook not to actively support the candidature of James’s son.

The representatives of the Dutch Republic, England, and Spain signed the treaty on 20 September 1697. Emperor Leopold, desperate for a continuation of the war so as to strengthen his own claims to the Spanish succession initially resisted the treaty, but because he was still at war with the Turks, and could not face fighting France alone, Leopold also sought terms and signed on 30 October.[81] However, the Emperor had netted an enormous accretion of power: Leopold’s son, Joseph, had been named King of the Romans, and the Emperor’s candidate for the Polish throne, August of Saxony, had carried the day over Louis’ candidate, the Prince of Conti. Additionally, Prince Eugene of Savoy’s decisive victory over the Ottoman Turks at the Battle of Zenta – leading to the Treaty of Karlowitz in 1699 – consolidated the Austrian Habsburgs and tipped the European balance of power in favour of the Emperor.[82] The Treaty of Ryswick covered the colonial disputes in one comprehensive clause: all places captured in North America were to be restored on both sides within six months.[83] Beyond this, the French gained recognition of their ownership of half of the island of Saint-Domingue.

The war had allowed William to destroy militant Jacobitism and helped bring Scotland and Ireland under more direct control; William also continued to prioritise the security of the Dutch Republic. In 1698 the Dutch garrisoned a series of fortresses in the Spanish Netherlands as a barrier to French attack – future Dutch foreign policy would centre around the maintenance and extension of these barrier fortresses.[84] However, the question of the Spanish inheritance was not discussed at Ryswick, and it remained the most important unsolved question of European politics. Within three years, King Charles II would be dead, and Louis XIV and the Grand Alliance would again plunge Europe into conflict – the War of the Spanish Succession.

Weapons, technology, and the art of war

Military developments

The campaign season typically lasted through May to October; due to lack of fodder campaigns in winter were rare but the French practice of storing food and provisions in magazines brought them considerable advantage, often enabling them to take to the field weeks before their foes.[85] Nevertheless, military operations during the Nine Years’ War did not produce decisive results. The war was dominated by what may be called ‘positional warfare’ – the construction, defence, and attack of fortresses and entrenched lines. Many lesser commanders welcomed these relatively predictable, static operations to mask their lack of military ability.[86] As Daniel Defoe observed in 1697, "Now it is frequent to have armies of 50,000 men of a side [who] spend the whole campaign in dodging – or, as it is genteelly called – observing one another, and then march off into winter quarters."[86] Positional warfare played a wide variety of roles: fortresses controlled bridgeheads and passes, guarded supply routes, and served as storehouses and magazines. However, fortresses hampered the ability to follow success on the battlefield – defeated armies could flee to friendly fortifications, enabling them to recover and rebuild their numbers from less threatened fronts.[87]

Another contributing factor for the lack of decisive action was the necessity to fight in order to secure resources. Armies were expected to support themselves in the field by imposing contributions (taxing local populations) upon a hostile, or even neutral, territory. Subjecting a particular area to contributions was deemed more important than pursuing a defeated army from the battlefield in order to bring about its complete destruction; it was primarily the financial concerns and the availability of resources that shaped campaigns in an effort to outlast the enemy in a long war of attrition.[88]

The major advancement in weapon technology in the 1690s was the introduction of the flintlock musket. The flintlock firing mechanism provided superior rates of fire and accuracy over the cumbersome matchlocks. But the adoption of the flintlock was not initially universal; until 1697 for every three Allied soldiers that were equipped with the new flintlocks, two soldiers were still handicapped by matchlocks.[89] These weapons were further enhanced with the development of the socket-bayonet. Its predecessor, the plug-bayonet – jammed down the firearm’s barrel – not only prevented the musket from firing but was also a clumsy weapon that took time to fix properly, and even more time to unfix. In contrast, the socket-bayonet could be drawn over the musket’s muzzle and locked into place by a lug, converting the musket into a short pike but leaving it capable of fire.[90]

The largest French ships of the period were the Soleil Royal and the Royal Louis, both rated at 120 guns, but which never carried their full compliment of cannon. These ships, though, were too large for practical purposes: the former only sailed on one campaign and was destroyed at La Hogue; the latter languished in port until its sale in 1694. By the 1680s French ship design was at least equal to their English and Dutch counterparts, and by the time of the Nine Years’ War they had surpassed ships of the Royal Navy whose designs had stagnated in the 1690s.[91] Innovation in the Royal Navy, however, did not cease. At some stage in the 1690s for example, English ships began to employ the steering wheel, greatly improving their performance particularly in heavy weather; the French navy did not adopt the wheel for another thirty years.[92]

Combat between naval fleets was decided by cannon duels delivered by ships in line of battle; fireships were also utilised but were mainly successful against anchored and stationary targets, whilst the new bomb vessels were best utilised as shore bombardment. Yet sea battles were rarely decisive and it was almost impossible to inflict enough damage on ships and men to win a clear victory; ultimate success depended not on tactical brilliance but on sheer weight of numbers.[93] Here Louis was at a disadvantage: without as large a maritime commerce as benefited the Allies, the French were unable to supply as many experienced sailors for their navy. Most importantly, though, Louis had to concentrate his resources on the army at the expense of the fleet, enabling the Dutch, and the English in particular, to outdo the French in ship construction. However, naval actions were comparatively uncommon and, just like battles on land, the goal was generally to outlast rather than destroy one’s opponent. To King Louis, his fleet was an extension of his army whose most important role was to protect the French coast from enemy invasion. He utilised his navy to support land and amphibious operations or the bombardment of coastal targets, designed to draw enemy resources from elsewhere and thus aid his land campaigns on the continent.[94]

Notes

- ↑ All dates in the article are in the Gregorian calendar (unless otherwise stated). The Julian calendar as used in England until 1700 differed by ten days. Thus, the Battle of the Boyne was fought on 11 July (Gregorian calendar) or 1 July (Julian calendar). In this article (O.S) is used to annotate Julian dates with the year adjusted to 1 January. See the article Old Style and New Style dates for a more detailed explanation of the dating issues and conventions.

- ↑ 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica, 11th Edition, New York 1910, Vol.X, p.460: "The oriflamme and the Chape de St Martin were succeeded at the end of the 16th century, when Henry III., the last of the house of Valois, came to the throne, by the white standard powdered with fleurs-de-lis. This in turn gave place to the famous tricolour."George Ripley, Charles Anderson Dana, The American Cyclopaedia, New York, 1874, p. 250, "...the standard of France was white, sprinkled with golden fleur de lis...". *[1]The original Banner of France was strewn with fleurs-de-lis. *[2]:on the reverse of this plate it says: "Le pavillon royal était véritablement le drapeau national au dix-huitième siecle...Vue du chateau d'arrière d'un vaisseau de guerre de haut rang portant le pavillon royal (blanc, avec les armes de France)."

- ↑ The Dutch army grew from a peacetime strength of 40,000 in 1686 to a peak of 102,000 in 1696. The English army expanded from 40,000 in 1688 to 101,000 in 1696. Spain maintained approximately 50,000 troops throughout the war. Brandenburg-Prussian forces numbered some 30,000 in 1688; smaller German states managed between 6,000 and 10,000 during the war. Savoy had an initial strength of some 8,000 men, rising to 26,000 in 1696. All coalition armies hired foreign soldiers to raise the numbers. These are paper figures.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Lynn p. 98. These naval figures are from 1695.

- ↑ This is a paper strength of officers and men in the French army – by far the largest in Europe. Its actual strength was probably nearer 340,000.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 161

- ↑ Doyle: Short Oxford History of France – Old Regime France, p. 182. Because of the vagaries of the language, the treaties of Westphalia and Nijmegen were notoriously imprecise, and often self-contradictory. The imprecision of treaty language often led to differing interpretations of the text; for example, one party could be awarded a town or district and its ‘dependencies’, without specifically stating what these dependencies were. France thus became plaintiff, judge, and executor of a legal process that awarded her territory.

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 37. Colmar, Weissembourg, Haguenau and other important Alsatian cities were effectively made part of France.

- ↑ The others being Breisach which was already in French hands, and Philippsburg, which the French lost by the Treaty of Nijmegen. Strasbourg was one of the ‘gates’ into the empire, and one which could be barred to the Imperialists should they seek entrance to Alsace.

- ↑ Piedmont was now hemmed in by two massive French-occupied fortresses: Casale on the eastern flank, and, on its western edge, Pinerolo, annexed by France fifty years earlier in defiance of the 1631 Treaty of Cherasco.

- ↑ Wolf: Louis XIV, p. 501

- ↑ Wolf: The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715, p. 19

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers 1648–1815, p. 38. Frederick William would not move against France. With French aid he hoped to conquer Pomerania.

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 38

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Wolf: The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715, p. 35

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Wolf: The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715, p. 36

- ↑ Miller: James II, p. 144. James' mother Henrietta Maria was the sister of Louis's father Louis XIII; William's mother, Mary, Princess Royal and Princess of Orange, was James's sister.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 40

- ↑ Miller: James II, p. 145: In England there was growing concern over James’s Catholicism but his treatment of the Huguenots within the country reflected the king’s principles: on a human level he sympathized with their persecution (realising also that it would be looked upon unfavourably by his mainly Protestant subjects if he did nothing), but on the other hand he distrusted them on political grounds. As early as July 1685 he had suspected the Huguenots had been mixed up in the Monmouth Rebellion.

- ↑ Wolf: The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715, p. 38

- ↑ Wolf: Louis XIV, p. 530. In May 1685 the Elector of the Palatine died without male heirs. Philip William von Pfaltz-Neuberg succeeded the Elector in accordance to the Treaty of Westphalia, but whilst his predecessor had remained close to France, the new Elector did not. The late Elector’s sister, Elizabeth-Charlotte, was the Duchess of Orléans, and King Louis XIV’s sister-in-law. Her inheritance to her late brother’s lands and property had to be resolved, and proved yet another source of diplomatic friction between the German princes and Louis.

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 181

- ↑ Wolf: Louis XIV, p. 520

- ↑ Wolf: Louis XIV, p. 529

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 42. The Bavarian Wittelsbachs traditionally provided the electoral bishop.

- ↑ Wolf: The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715, p. 41. Pope Innocent could not understand Louis refusal to aid the ‘crusade’ against the Ottomans, or his obstinate refusal to give up the franchise in Rome. The franchise was the right assumed by ambassadors to the papal court to grant asylum to anyone who applied for it in their embassies in Rome.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 42

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 192

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 194. Louis’ son, the Dauphin, formally commanded these troops, but he was a man of modest talents. Philippsburg was a natural target since it controlled the middle Rhine.

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 43

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 198

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 202

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Mckay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 44

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 50

- ↑ Wolf: The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715, p. 42

- ↑ Miller: James II, p. 209

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 203

- ↑ Kinross: The Boyne and Aughrim: The War of the Two Kings, p. 35

- ↑ Since James’s accession in 1685, the officer corps had become wholly Catholic (it had recently been wholly Protestant). Both the officers and men lacked experience – the army had been enlarged in the winter of 1688–89 so that a very high proportion of the regiments were new, and it was very poorly equipped. Its administration was open to corruption, and no provision was made for magazines, arsenals or hospitals.

- ↑ Kinross: The Boyne and Aughrim: The War of the Two Kings, p. 17

- ↑ Miller: James II, p. 228

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Wolf: The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715, p. 43

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 45

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 199

- ↑ Chandler: The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough, p. 31

- ↑ Childs: Warfare in the Seventeenth Century, p. 187

- ↑ Noailles, and his Spanish opponent Villahermosa, spent most of the summer simply observing one another before the French returned to Rousillon. De Lorge’s inferior army restricted him to a mainly defensive posture, keeping the enemy out of French territory and imposing contributions on German lands.

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 213

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 218. The defenders marched out on 10 April.

- ↑ Wolf: Louis XIV, p.564

- ↑ Rowlands: Louis XIV, Vittorio Amedeo II and French Military Failure in Italy, 1689-96. Taking these places not only denied potential springboards for land and amphibious attacks by the Allies on Provence, but their capture had facilitated French operations in southern Piedmont, enabling Catinat to take Avigliana in May, and Carmagnola on 9 June.

- ↑ Rowlands: Louis XIV, Vittorio Amedeo II and French Military Failure in Italy, 1689-96. Louis tried to win over Victor Amadeus and bring him to a peace settlement, but Amadeus, anticipating military superiority for the following year’s campaign, was not prepared to negotiate seriously.

- ↑ Surviving French forces from Ireland, together with 13,000 Irish troops, sailed for France. These Irish forces, the so-called Wild Geese, nominally owed their allegiance to James II. James had intended to use the Irish troops as part of a Franco-Irish assault on England, but the naval defeat at La Hogue had put an end to invasion plans. The Irish troops were transferred to other fronts.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 232

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 50

- ↑ Childs: Warfare in the Seventeenth Century, p. 192. The Irish troops marched off to the Rhineland and the French regiments joined the army in Flanders or were devoted to coastal defence.

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 237

- ↑ Doyle: Short Oxford History of France – Old Regime France, p. 184. The burden of funding the war fell upon this depleted economic base, inducing finance raising measures including taxing every conceivable commodity and transaction.

- ↑ Chandler: The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough, p. 53

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 236

- ↑ Childs: Warfare in the Seventeenth Century, p. 194

- ↑ Roger: The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815, p. 153. 30 million livres was equivalent to the entire French naval budget for 1692.

- ↑ Wolf: Louis XIV, p. 582

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 242

- ↑ Childs: Warfare in the Seventeenth Century, p. 197

- ↑ John Childs calls the recapture of Namur the most important event of the Nine Years' War.

- ↑ Childs: Warfare in the Seventeenth Century, p. 202

- ↑ Symcox: War, Diplomacy, and Imperialism: 1618–1763, p. 236: For Vauban’s Memorandum on Privateering, 1695, and Memorandum on the French Frontier, 1678, see Symcox

- ↑ Vauban wrote, "One does not need to be very learned to know that the English and Dutch are the main pillars of the Alliance ... At the same time they cannot attack us in this way, for we have little or no overseas territory ..."

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 102

- ↑ Childs: Warfare in the Seventeenth Century, p. 198. Victor Amadeus thought it would be to his advantage to have Casale dismantled and neutralized. Because of its position it would then be at the mercy of Savoy.

- ↑ Rowlands describes this as little short of a humiliation for Louis when set alongside French demands in the summer of 1690.

- ↑ Rowlands: Louis XIV, Vittorio Amedeo II and French Military Failure in Italy, 1689-96.

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 51

- ↑ Childs states 25,000 French troops.

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 261

- ↑ Guttridge: The Colonial Policy of William III in America and the West Indies, p. 45. It had been agreed that neither of the parties would violate the territories of the other in America or the West Indies no matter the situation in Europe.

- ↑ Taylor: American Colonies: The Settling of North America, p. 290

- ↑ Elson: History of the United States of America, pp. 162–165

- ↑ Childs: Warfare in the Seventeenth Century, p. 205

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 52

- ↑ Wolf: Louis XIV. p. 594

- ↑ Guttridge: The Colonial Policy of William III in America and the West Indies, p. 84

- ↑ McKay & Scott: The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815, p. 53

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, pp. 54-55

- ↑ 86.0 86.1 Chandler: The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough, p. 235

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, pp. 80-81

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, pp. 372–373

- ↑ Chandler: The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough, p. 78

- ↑ Childs: Warfare in the Seventeenth Century, p. 155

- ↑ Roger: The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815, p. 219

- ↑ Roger: The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815, p. 222

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 93

- ↑ Lynn: The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714, p. 103

References

- Chandler, David G. The Art of Warfare in the Age of Marlborough. Spellmount Limited, (1990). ISBN 0-946771-42-1

- Childs, John. Warfare in the Seventeenth Century. Cassell, (2003). ISBN 0-304-36373-1

- Doyle, William. Short Oxford History of France – Old Regime France. Oxford University Press, (2001). ISBN 0-19-873129-9

- Elson, Henry William. History of the United States of America. The MacMillan Company, (1905).

- Guttridge, George H. The Colonial Policy of William III in America and the West Indies. Frank Cass Publishers, (1966).

- Kinross, John. The Boyne and Aughrim: The War of the Two Kings. The Windrush Press, (1998). ISBN 1-900624-07-9

- Lynn, John A. The Wars of Louis XIV: 1667–1714. Longman, (1999). ISBN 0-582-05629-2

- McKay, Derek & Scott, H. M. The Rise of the Great Powers: 1648–1815. Longman, (1984). ISBN 0-582-48554-1

- Miller, John. James II. Yale University Press, (2000). ISBN 0-300-08728-4

- Roger N.A.M. The Command of the Ocean: A Naval History of Britain 1649–1815, Penguin Group, (2006). ISBN 0-141-02690-1

- Rowlands, Guy. Louis XIV, Vittorio Amedeo II and French Military Failure in Italy, 1689-96. (2000) [3]

- Storrs, Christopher. War, Diplomacy and the Rise of Savoy, 1690–1720. Cambridge University Press, (1999). ISBN 0-521-55146-3

- Symcox, Geoffrey. War, Diplomacy, and Imperialism: 1618–1763. Harper & Row, (1973). ISBN 06-139500-5

- Taylor, Alan. American Colonies: The Settling of North America. Penguin Books, (2002). ISBN 0-14-200210-0

- Wolf, John B. The Emergence of the Great Powers: 1685–1715. Harper & Row, (1962). ISBN 0061397509

- Wolf, John B. Louis XIV. Panther Books, (1970). ISBN 0-586-03332-7