Nerve

Nerves (yellow)

A nerve is an enclosed, cable-like bundle of peripheral axons (the long, slender projections of neurons). A nerve provides a common pathway for the electrochemical nerve impulses that are transmitted along each of the axons. Nerves are found only in the peripheral nervous system. In the central nervous system, the analogous structures are known as tracts. [1][2]

Neurons are sometimes called nerve cells, though this term is technically inaccurate since many neurons do not form nerves, and nerves also include non-neuronal Schwann cells that coat the axons in myelin.

Anatomy

Nerves are categorized into three groups based on the direction that signals are conducted:

- Afferent nerves conduct signals from sensory neurons to the central nervous system, for example from the mechanoreceptors in skin.

- Efferent nerves conduct signals from the central nervous system along motor neurons to their target muscles and glands.

- Mixed nerves contain both afferent and efferent axons, and thus conduct both incoming sensory information and outgoing muscle commands in the same bundle.[1][2]

Nerves can be categorized into two groups based on where they connect to the central nervous system:

- Spinal nerves innervate much of the body, and connect through the spinal column to the spinal cord. They are given letter-number designations according to the vertebra through which they connect to the spinal column.

- Cranial nerves innervate parts of the head, and connect directly to the brainstem. They are typically assigned Roman numerals from I to XII, although cranial nerve zero is sometimes included. In addition, cranial nerves have descriptive names.[2]

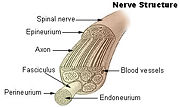

Anatomy of a nerve.

Each nerve is covered externally by a dense sheath of connective tissue, the epineurium. Underlying this is a layer of flat cells, the perineurium, which forms a complete sleeve around a bundle of axons. Perineurial septae extend into the nerve and subdivide it into several bundles of fibers. Surrounding each such fibre is the endoneurium. This forms an unbroken tube which extends from the surface of the spinal cord to the level at which the axon synapses with its muscle fibers, or ends in sensory receptors. The endoneurium consists of an inner sleeve of material called the glycocalyx and an outer, delicate, meshwork of collagen fibers. Nerves are bundled along with blood vessels, since the neurons of a nerve have fairly high energy requirements.[2]

Within the endoneurium, the individual nerve fibers are surrounded by a low protein liquid called endoneurial fluid. The endoneurium has properties analogous to the blood-brain barrier, in that it prevents certain molecules from crossing from the blood into the endoneurial fluid. In this respect, endoneurial fluid is similar to cerebro-spinal fluid in the central nervous system.[2] During the development of nerve edema from nerve irritation or injury, the amount of endoneurial fluid may increase at the site of irritation. This increase in fluid can be visualized using Magnetic resonance neurography, and thus MR neurography can identify nerve irritation and/or injury.

Physiology

A nerve conveys information in the form of electrochemical impulses (known as nerve impulses or action potentials) carried by the individual neurons that make up the nerve. These impulses are extremely fast, with some myelinated neurons conducting at speeds up to 120 m/s. The impulses travel from one neuron to another by crossing a synapse, which can be either electrical or chemical in nature.[1][2]

Nerves can be categorized into two groups based on function:

- Sensory nerves conduct sensory information from their receptors to the central nervous system, where the information is then processed. Thus they are synonymous with afferent nerves.

- Motor nerves conduct signals from the central nervous system to muscles. Thus they are synonymous with efferent nerves.[1][2]

Clinical importance

Damage to nerves can be caused by physical injury, swelling (e.g. carpal tunnel syndrome), autoimmune diseases (e.g. Guillain-Barré syndrome), infection (neuritis), diabetes or failure of the blood vessels surrounding the nerve. A pinched nerve occurs when pressure is placed on a nerve, usually from swelling due to an injury or pregnancy. Nerve damage or pinched nerves are usually accompanied by pain, numbness, weakness, or paralysis. Patients may feel these symptoms in areas far from the actual site of damage, a phenomenon called referred pain. Referred pain occurs because when a nerve is damaged, signalling is defective from all parts of the area from which the nerve receives input, not just the site of the damage. Neurologists usually diagnose disorders of the nerves by a physical examination, including the testing of reflexes, walking and other directed movements, muscle weakness, proprioception, and the sense of touch. This initial exam can be followed with tests such as nerve conduction study and electromyography (EMG).

Nerve Growth & stimulation

Nerve growth normally ends in adolescence, but can be re-stimulated with a molecular mechanism known as "Notch signaling", working on a Notch receptor:

Yale Study Shows Way To Re-Stimulate Brain Cell Growth ScienceDaily (Oct. 22, 1999) — Results Could Boost Understanding Of Alzheimer's, Other Brain Disorders http://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/1999/10/991022005127.htm

See also

Additional images

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 Purves, Dale, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, William C. Hall, Anthony-Samuel LaMantia, James O. McNamara, and Leonard E. White (2008). Neuroscience. 4th ed.. Sinauer Associates. pp. 11–20. ISBN 978-0-87893-697-7.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 2.3 2.4 2.5 2.6 Elaine N. Marieb and Katja Hoehn (2007). Human Anatomy & Physiology (7th Ed.). Pearson. pp. 388–602. ISBN 0-805-35909-5.

|

Nerves: spinal nerves |

|

| Cervical (8) |

C1, C2, C3, C4, C5, C6, C7, C8

anterior (Cervical plexus, Brachial plexus) - posterior (Posterior branches of cervical nerves, Suboccipital - C1, Greater occipital - C2, Third occipital - C3)

|

|

| Thoracic (12) |

T1, T2, T3, T4, T5, T6, T7, T8, T9, T10, T11, T12

anterior (Intercostal, Intercostobrachial - T2, Thoraco-abdominal nerves - T7-T11, Subcostal - T12) - posterior (Posterior branches of thoracic nerves)

|

|

| Lumbar (5) |

L1, L2, L3, L4, L5

anterior (Lumbar plexus, Lumbosacral trunk) - posterior (Posterior branches of the lumbar nerves, Superior cluneal L1-L3)

|

|

| Sacral (5) |

S1, S2, S3, S4, S5

anterior (Sacral plexus) - posterior (Posterior branches of sacral nerves, Medial cluneal nerves)

|

|

| Coccygeal (1) |

anterior (Coccygeal plexus) - posterior (Posterior branch of coccygeal nerve)

|

|

|

Nerves of head and neck: the cranial nerves and nuclei |

|

| olfactory (AON->I) |

olfactory bulb - olfactory tract

|

|

| optic (LGN->II) |

optic chiasm - optic tract

|

|

| oculomotor (ON,EWN->III) |

superior branch (parasympathetic root of ciliary ganglion/ciliary ganglion) - inferior branch

|

|

| trochlear (TN->IV) |

no significant branches

|

|

| trigeminal (PSN,TSN,MN,TMN->V) |

trigeminal ganglion • ophthalmic • maxillary • mandibular

|

|

| abducens (AN->VI) |

no significant branches

|

|

| facial (FMN,SN,SSN->VII) |

|

near origin

|

nervus intermedius • geniculate

|

|

|

inside facial canal

|

greater petrosal (pterygopalatine ganglion) - nerve to the stapedius - chorda tympani (lingual nerve, submandibular ganglion)

|

|

|

at stylomastoid foramen

|

posterior auricular - suprahyoid (digastric, stylohyoid) - parotid plexus (temporal, zygomatic, buccal, mandibular, cervical)

|

|

|

| vestibulocochlear (VN,CN->VIII) |

cochlear (striae medullares, lateral lemniscus) • vestibular (Scarpa's ganglion)

|

|

| glossopharyngeal (NA,ISN,SN->IX) |

|

before jugular fossa

|

ganglia (superior, inferior)

|

|

|

after jugular fossa

|

tympanic (tympanic plexus, lesser petrosal, otic ganglion) • stylopharyngeal branch • pharyngeal branches • tonsillar branches • lingual branches • carotid sinus

|

|

|

| vagus (NA,DNVN,SN->X) |

|

before jugular fossa

|

ganglia (superior, inferior)

|

|

|

after jugular fossa

|

meningeal branch - auricular branch

|

|

|

|

pharyngeal branch (pharyngeal plexus) - superior laryngeal (external, internal) - recurrent laryngeal (inferior) - superior cervical cardiac

|

|

|

thorax

|

inferior cardiac - pulmonary - vagal trunks (anterior, posterior)

|

|

|

|

celiac - renal - hepatic - anterior gastric - posterior gastric

|

|

|

| accessory (NA,SAN->XI) |

cranial - spinal

|

|

| hypoglossal (HN->XII) |

lingual branches

|

|

|

Nerves of head and neck: the cervical plexus (C1-C4) |

|

| superficial |

C2: Lesser occipital,

C2-C3:Greater auricular • Transverse cervical

C3-C4: Supraclavicular

|

|

| deep |

C1-C3: Ansa cervicalis (superior root, inferior root)

C3-C5: Phrenic

|

|

|

Nerves of upper limbs (primarily): the brachial plexus (C5-T1) |

|

| Supraclavicular |

root (dorsal scapular, long thoracic) - upper trunk (suprascapular, to the subclavius)

|

|

| Infraclavicular |

|

lateral cord

|

lateral pectoral

musculocutaneous (lateral cutaneous of forearm)

median/lateral root: anterior interosseous - palmar - recurrent - common palmar digital (proper palmar digital) |

|

|

medial cord

|

medial pectoral

cutaneous: medial cutaneous of forearm • medial cutaneous of arm

ulnar: muscular - palmar - dorsal (dorsal digital nerves) - superficial (common palmar digital, proper palmar digital) - deep

median/medial root: see above |

|

|

posterior cord

|

subscapular (upper, lower) • thoracodorsal

axillary (superior lateral cutaneous of arm)

radial: muscular - cutaneous (posterior of arm, inferior lateral of arm, posterior of forearm) - superficial (dorsal digital nerves) - deep (posterior interosseous) |

|

|

| Other |

cutaneous innervation of the upper limbs

|

|

|

Nerves - autonomic nervous system (sympathetic nervous system/ganglion/trunks and parasympathetic nervous system/ganglion) |

|

| Head/cranial |

Ciliary ganglion: roots (Sensory, Parasympathetic, Sympathetic) - Short ciliary

Pterygopalatine ganglion: deep petrosal - nerve of pterygoid canal

branches of distribution: greater palatine (inferior posterior nasal branches) - lesser palatine - nasopalatine (medial superior posterior nasal branches) - pharyngeal

Submandibular ganglion

Otic ganglion |

|

| Neck/cervical |

paravertebral ganglia: Cervical ganglia (Superior, Middle, Inferior) - Stellate ganglion

prevertebral plexus: Cavernous plexus - Internal carotid

|

|

| Chest/thorax |

paravertebral ganglia: Thoracic ganglia

prevertebral plexus: Cardiac plexus - Esophageal plexus - Pulmonary plexus - Thoracic aortic plexus

splanchnic nerves: cardiopulmonary - thoracic

cardiac nerves: Superior - Middle - Inferior

|

|

| Abdomen/Lumbar |

paravertebral ganglia: Lumbar ganglia

prevertebral ganglia: Celiac ganglia (Aorticorenal) - Superior mesenteric ganglion - Inferior mesenteric ganglion

prevertebral plexus: Celiac plexus - (Hepatic, Splenic, Pancreatic) - aorticorenal (Abdominal aortic plexus, Renal/Suprarenal) - Superior mesenteric (Gastric) - Inferior mesenteric (Spermatic, Ovarian) - Superior hypogastric (hypogastric nerve, Superior rectal) - Inferior hypogastric (Vesical, Prostatic/Cavernous nerves of penis, Uterovaginal, Middle rectal)

splanchnic nerves: Lumbar splanchnic nerves

enteric nervous system: Meissner's plexus • Auerbach's plexus

|

|

| Pelvis/sacral |

paravertebral ganglia: Sacral ganglia - Ganglion impar

splanchnic nerves: Pelvic splanchnic nerves - Sacral splanchnic nerves

|

|

| All |

Rami communicans (White, Gray) - Preganglionic fibers - Postganglionic fibers

|

|

|

Nerves of lower limbs and lower torso: the lumbosacral plexus (L1-Co) |

|

| lumbar plexus (L1-L4) |

|

iliohypogastric

|

lateral cutaneous branch - anterior cutaneous branch

|

|

|

ilioinguinal

|

anterior scrotal ♂/labial ♀

|

|

|

genitofemoral

|

femoral branch/lumboinguinal - genital branch

|

|

|

lateral cutaneous of thigh

|

patellar

|

|

|

obturator

|

anterior (cutaneous) - posterior - accessory

|

|

|

femoral

|

anterior cutaneous branches - saphenous (infrapatellar, medial crural cutaneous)

|

|

|

| sacral plexus (L4-S4) |

|

sciatic

|

|

common fibular

|

lateral sural cutaneous (sural communicating branch) - deep fibular (lateral terminal branch, medial terminal branch, dorsal digital) - superficial fibular (medial dorsal cutaneous, intermediate dorsal cutaneous, dorsal digital)

|

|

|

tibial

|

medial sural cutaneous - medial calcaneal - medial plantar (common plantar digital nerves, proper plantar digital) - lateral plantar (deep branch, superficial branch, common plantar digital, proper plantar digital)

|

|

|

sural

|

lateral dorsal cutaneous - lateral calcaneal

|

|

|

|

other

|

muscular: superior gluteal/inferior gluteal - lateral rotator group (to quadratus femoris, to obturator internus, to the piriformis)

cutaneous: posterior cutaneous of thigh (inferior cluneal, perineal branches) - perforating cutaneous

|

|

|

| coccygeal plexus (S4-Co) |

pudendal: inferior anal - perineal (deep, posterior scrotal ♂/labial ♀) - dorsal of the penis ♂/clitoris ♀

anococcygeal

|

|

|

cutaneous innervation of the lower limbs

|

|