Necktie

The necktie (or tie) is a long piece of cloth worn around the neck, resting under the shirt collar and knotted at the throat. The modern necktie, ascot, and bow tie are descended from the cravat. Men wear neckties as part of regular office attire or formal wear. Neckties can also be worn as part of a uniform (e.g. military, school, waitstaff). Neck ties are generally unsized, but may be available in longer size.

Variants include the bow tie, ascot tie, bola tie, and the clip-on tie.

Contents |

History

Ancient neckties

- For the history of the tie, see also Cravat.

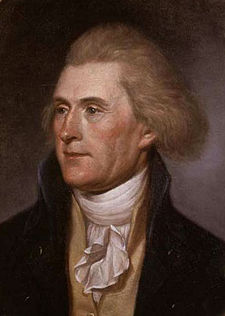

Regardless of the fact that the definition of the necktie in most dictionaries states "a large band of fabric worn around the neck under the collar and tied in front with the ends hanging down as a decoration", its history says a lot more. Men have always found it necessary to tie something around their necks. The earliest historical example is in ancient Egypt. The rectangular piece of cloth that was tied and hung down till the shoulders was a very important part of an Egyptian’s clothing because it showed his social status. In China, all the statues around the grave of Emperor Shi Huang Ti bear a piece of cloth around their necks, which is considered an ancestor of the modern necktie. In art from the Roman Empire, men are also depicted bearing neckwear that much resembles the contemporary necktie.

The necktie can be traced back to the time of the Thirty Years' War (1618-1648) when Croatian mercenaries in French service, wearing their traditional small, knotted neckerchiefs, aroused the interest of the Parisians.[1] The new article of clothing started a fashion craze in Europe where both men and women wore pieces of fabric around their necks. In the late seventeenth century, the men wore lace cravats that took a large amount of time and effort to arrange. These cravats were often tied in place by cravat strings, arranged neatly and tied in a bow.

1650-1720: the Steinkirk

The Battle of Steenkerque took place in 1692. In this battle, the princes, while hurriedly dressing for battle, just wound these cravats around their necks. They twisted the ends of the fabric together and passed the twisted ends through a jacket buttonhole. These cravats were generally referred to as Steinkirks.

1720-1800: Stocks, Solitaires, Neckcloths, Cravats

In 1715, another kind of neckwear, called "Stocks" made its appearance. Stocks were initially just a small piece of muslin folded into a narrow band wound a few times round the shirt collar and secured from behind with a pin. It was fashionable for the men to wear their hair long, past shoulder length. The ends were tucked into a black silk bag worn at the nape of the neck. This was known as the bag-wig hairstyle, and the neckwear worn with it was the stock.

A variation of the bag wig would be the solitaire. This form had matching ribbons stitched around the bag. After the stock was in place, the ribbons would be brought forward and tied in a large bow in front of the wearer.

Sometime in the late eighteenth century, cravats began to make an appearance again. This can be attributed to a group of young men called the maccaronis (of Yankee Doodle fame). These were young Englishmen who returned from Europe and brought with them new ideas about fashion from Italy. The French contemporaries of the maccaronis were the Incroyables.

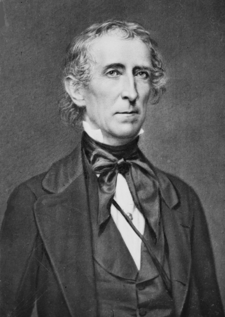

1800-1850: Cravat, Stocks, Scarves, Bandannas

At this time, there was also much interest in the way to tie a proper cravat and this led to a series of publications. This began with Neckclothitania, which is a book that contained instructions and illustrations on how to tie 14 different cravats. It was also the first book to use the word ‘tie’ in association with neckwear.

It was about this time that black stocks made their appearance. Their popularity eclipsed the white Cravat, except for formal and evening wear. These remained popular through to the 1850s. At this time, another form of neckwear worn was the scarf. This was where a neckerchief or bandanna was held in place by slipping the ends through a finger or scarf ring at the neck instead of using a knot. This is the classic sailor neckwear and may have been adopted from them.

1860-1920s: Bow ties, Scarf/Neckerchief, the Ascot, the Long tie

The industrial revolution created a need for neckwear that was easy to put on, comfortable and would last an entire workday. The modern necktie, as is still worn by millions of men today, was born. It was long, thin and easy to knot and it didn’t come undone.

The English called it the “four in hand” because the knot resembled the reins of the four horse carriage used by the British upper class. By this time, the sometimes complicated array of knots and styles of neckwear gave way to the neckties and bow ties, the latter a much smaller, more convenient version of the cravat. In formal dinner parties and when attending races, another type of neckwear was considered de rigueur; this was the Ascot tie, which had wide flaps that were crossed and pinned together on the chest.

This was until 1926, when a New York tie maker, Jesse Langsdorf came up with a method of cutting the fabric on the bias and sewing it in three segments. This technique improved elasticity and facilitated the fabric's return to its original shape. Since that time, most men have worn the “Langsdorf” tie. Yet another development of that time was the method used to secure the lining and interlining once the tie had been folded into shape. Richard Atkinson and Company of Belfast claim to have introduced the slipstitch for this purpose in the late 1920s.

1920s-present day

After the First World War, hand-painted ties became an accepted form of decoration in America. The widths of some of these ties went up to 4.5 inches (110 mm). These loud, flamboyant ties sold very well all the way through the 1950s.

In Britain, Regimental stripes have been continuously used in tie designs since the 1920s. Traditionally, English stripes ran from the left shoulder down to the right side; however, when Brooks Brothers introduced the striped ties in the United States around the beginning of the 20th century, they had theirs cut in the opposite direction.

Before the Second World War ties were worn shorter as well as wider than they are today; although in Britain in the 1970s short and wide ties (known as 'Kipper ties') became fashionable for a few years.

The 1960s brought about an influx of pop art influenced designs. The first was designed by Michael Fish when he worked at Turnbull & Asser. The term kipper was a pun on his name. The exuberance of the styles of the late 1960s and early 1970s gradually gave way to more restrained designs. Ties became narrower, returning to their 2-3 inch width with subdued colors and motifs, traditional designs of the 1930s and 1950s reappeared, particularly Paisley patterns. Ties began to be sold along with shirts and designers slowly began to experiment with bolder colors.

This continued in the 1980s, when very narrow ties approximately 1 inch wide became popular. Into the 1990s, increasingly unusual designs became common, such as joke ties or deliberately kitsch ties designed to make a statement. These included ties featuring cartoon characters or made of unusual materials such as plastic or wood.

Types

Cravat

In 1660, in celebration of its hard-fought victory over the Ottoman Empire, a crack regiment from Croatia visited Paris. There, the soldiers were presented as glorious heroes to Louis XIV, a monarch well known for his eye toward personal adornment. It so happened that the officers of this regiment were wearing brightly colored handkerchiefs fashioned of silk around their necks. These neck cloths struck the fancy of the king, and he soon made them an insignia of royalty as he created a regiment of Royal Cravattes. The word "cravat" is derived from the "à la croate" - like the Croats (wear them).

Four-in-hand

The four-in-hand necktie (as distinct from the four-in-hand knot) was fashionable in Great Britain in the 1850s. Early neckties were simple, rectangular cloth strips cut on the square, with square ends. The term "four-in-hand" originally described a carriage with four horses and a driver; later, it also was the name of a London gentlemen's club. Some etymologic reports are that carriage drivers knotted their reins with a four-in-hand knot (see below), whilst others claim the carriage drivers wore their scarves knotted 'four-in-hand', but, most likely, members of the club began wearing their neckties so knotted, thus making it fashionable. In the latter half of the 19th century, the four-in-hand knot and the four-in-hand necktie were synonymous. As fashion changed from stiff shirt collars to soft, turned-down collars, the four-in-hand necktie knot gained popularity; its sartorial dominance rendered the term "four-in-hand" redundant usage, shortened "long tie" and "tie".

In 1926, Jesse Langsdorf from New York introduced ties cut on the bias (US) or cross-grain (UK), allowing the tie to evenly fall from the knot without twisting; this also caused any woven pattern such as stripes to appear diagonally across the tie.

Today, four-in-hand ties are part of men's formal clothing in both Western and non-Western societies, particularly for business.

Four-in-hand ties are generally made from silk, cotton, polyester or, common before World War II but not as popular nowadays, wool. They appear in a very wide variety of colours and patterns, notably striped (often diagonally), club ties (often with a small motif repeated regularly all over the tie) and solids. "Novelty ties" featuring icons from popular culture (such as cartoons, actors, holiday images), sometimes with flashing lights, have been quite prevalent since the 1990s, as have paisley ties.

Six- and seven-fold tie

The sevenfold tie is a construction variant of the four-in-hand necktie revived after the austerity of the Great Depression. A square yard of silk (usually two or more pieces sewn together) is folded to seven sections of silk between the folds. Its weight and body derive exclusively from the layering of silk. It can require an hour or more to construct.

There are newly designed spinoffs to sevenfold ties, often referred to as four folds, or lined seven folds. These imposters frequently have the folds of the silk ending halfway through the middle of the inside of the tie. These ties, while very thick, are essentially the same as regular lined ties, with the exception of the decorative origami like folds at the ends of the tie. They are most easily identified by the bottom square, the part of the back of the tie that hangs in front of the belt, which is not one single sheet of silk-normally the introverted pattern is exposed-but is two pieces of the silk with the liner in between. In contrast to authentic sevenfolds, these ties' heft and body are derived by the weight of created by the folding of the silk upon itelf.

These other "seven-fold ties" are also referred to as Six-fold ties. They are typically self-tipped and lined. These are historically Italian made, although they are increasingly being made elsewhere. For this reason, they are often referrd to as being "Italian style", while the sevenfold tie is usually untipped, unlined and is the "American style". The Talbott (Robert) Family is often credited with bringing back the sevenfold design which was almost lost as a result of the 1920s era depression. It was much more expensive to make a tie completely of silk, so the lined tie with other tiping fabric was born. The classic sevenfold tie has no interfacing (interlining) of any kind yet drapes beautifully due to the weight derived from the precise folding of the silk upon itself. Generally a medium weight, 25-30mm, silk is best used for creating one of these truly handmade ties.

Clip-on tie

The clip-on necktie is permanently knotted bow tie or four-in-hand style affixed with a metal clip to the front of the shirt collar. This 20th-century innovation is considered by some to be stylistically inferior, but may be considered appropriate by some for wear in occupations (e.g., law enforcement, service clerks, airline pilots, etc.) where a traditional necktie could pose a safety hazard. Clip-on ties are also the most common form of child-sized ties.

Types of knots

- See also Category:Necktie knots

A half windsor knot with a dimple also known as american knot

There are four main knots used to knot neckties. The simplest, the four-in-hand knot, may be the most common. The others (in order of difficulty) are:

The Windsor knot is named after the Duke of Windsor, although he did not invent it. The Duke did favour a voluminous knot; however, he achieved this by having neckties specially made of thicker cloths. In the late 1990s, two researchers, Thomas Fink and Yong Mao of Cambridge's Cavendish Laboratory, used mathematical modeling to discover that eighty-five (85) knots are possible with a conventional tie. (They limited the number of "moves" used to tie the knot to nine; longer sequences of moves result in too large a knot or leave the hanging ends of the tie too short.)[1] Ties as signs of membershipThe two variants of the school tie for Phillips Academy. The striped version uses American-style stripes (high side of stripe on wearer's right).

A cryptic motif on the official WE.177 project tie.

The use of coloured and patterned neckties indicating the wearer's membership in a club, military regiment, school, et cetera, dates only from late-nineteenth century England. The first definite occurrence was in 1880, when Exeter College, Oxford rowers took the College-colour ribbons from their straw boaters and wore them as neckties (knotted four-in-hand), and then went on to order a proper set of ties in the same colours, thus creating the first example of a college necktie. Soon other colleges followed suit, as well as schools, universities, and clubs. At about the same time, the British military moved from dressing in brightly and distinctively coloured uniforms to subdued and discreet uniforms, and they used neckties to retain regimental colours. Some secondary schools in the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand maintain the wearing of a tie as part of their school uniforms, with its design being specified. Some primary schools also permit pupils to wear ties. The most common pattern for such ties in the UK and most of Europe consists of diagonal stripes of alternating colours running down the tie from the wearer's left. Note that neckties are cut on the bias (diagonally), so the stripes on the source cloth are parallel or perpendicular to the selvage, not diagonal. The colours themselves may be particularly significant. The dark blue and red regimental tie of the Household Cavalry is said to represent the blue blood (i.e. nobility) of the Royal Family, and the red blood of the Guards. In the United States, diagonally striped ties are commonly worn with no connotation of group membership. Typically, American striped ties have the stripes running downward from the wearer's right (the opposite of the European style). However, when Americans wear striped ties as a sign of membership, the European stripe style may be used. An alternative membership tie pattern to diagonal stripes is either a single emblem or a crest centred and placed where a tie pin normally would be, or a repeated pattern of such motifs. Sometimes, both types are used by an organisation, either simply to offer a choice or to indicate a distinction among and levels of membership. Occasionally, a hybrid design is used, in which alternating stripes of colour are overlaid with repeated motif pattern. Many British schools use variations on their basic necktie to indicate the wearer's age, house, status (e.g. prefect), or participation in competition (especially sports). Usually, the Old Boys and Girls (alumni) wear a different design. Opposition to and problems with necktiesThe debate between proponents and opponents of the necktie center on social conformity, professional expectation, and personal, sartorial expression. Quoting architect Louis Sullivan, Frank Lloyd Wright said: "Form follows function". Applied sartorially, the necktie's decorative function is so criticized. Health issuesNecktie opponents cite risks of wearing a necktie as argument for discontinuing it. Their cited risks are entanglement, infection, and vasoconstriction. Entanglement when working with machinery or dangerous, possibly violent jobs such as policemen and prison guards, and certain medical fields. [2] The answer is to avoid wearing neckties, or to wear pre-knotted neckties that easily detach from the wearer when grabbed; vascular constriction occurs with over-tight collars. Studies have shown increased intraocular pressure in such cases, which can aggravate the condition of people with weakened retinas.[3] There may be additional risks for people with glaucoma. Sensible precautions can mitigate the risk. Paramedics performing life support remove an injured man's necktie as a first step to ensure it does not block his airway. Neckties might also be a health risk for persons other than the wearer. They are believed to be major vectors in disease transmission in hospitals. Notwithstanding such fears, doctors and dentists wear neckties for a professional image. Hospitals take seriously the cross-infection of patients by doctors wearing infected neckties, [4] because neckties are less frequently cleaned than most other clothes. On 17 September 2007, British hospitals published rules banning neckties.[5] Anti-necktie sentimentIn the early 20th century, the number of office workers began increasing. Many such men and women were required to wear neckties, because it was perceived as improving work attitudes, morale, and sales. Removing the necktie as a social and sartorial business requirement (and sometimes forbidding it) is a modern trend often attributed to the rise of popular culture. Although it was common as everyday wear as late as 1966, over the years 1967–69, the necktie fell out of fashion almost everywhere, except where required. There was a resurgence in the 1980s, but in the 1990s, ties again fell out of favor, with many Internet-based companies having very casual dress requirements. In North America, a phenomemon known as Casual Friday has arisen, in which employees were not required to wear ties on Fridays, and then — increasingly — on other, announced, special days. Some businesses extended casual-dress days to Thursday, and even Wednesday; others required neckties only on Monday (to start the work week). At the furniture company IKEA, neckties are not allowed. An extreme example of anti-necktie sentiment is found in Iran, whose theocratic rulers have denounced the accessory as a decadent symbol of Western oppression. In the late 1970s (at the time of the Islamic Revolution) members of the US press even metonymized Iran's hardliners as turbans and its moderates as neckties. To date, most Iranian men have retained the Western-style long-sleeved collared shirt and three-piece suit, while excluding the necktie.[2][3] Neckties are viewed by various sub and counter culture movements as being a symbol of submission and slavery (ie having a symbolic chain around ones neck) to the corrupt elite of society, as a "wage-slave". Designers of necktiesFor 60 years, designers and manufacturers of neckties were members of the Men's Dress Furnishings Association but the trade group shut down in 2008 due to declining membership due to the declining numbers of men wearing neckties.[6] Some of the finest[7] designer ties are:

Use by womenNeckties are sometimes part of uniforms worn by women, particularly at restaurants and hotels. Many secondary school students in countries requiring ties also require girls to wear them as part of the uniform. It can also be used by women as a fashion statement, becoming especially popular after Diane Keaton wore a tie as the titular character in Annie Hall. [8] See also

References

Further reading

External linksNecktie knots at the Open Directory Project

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||