Near-Earth asteroid

Near-Earth asteroids (NEAs) are asteroids whose orbits are close to Earth's orbit. All near-Earth asteroids spend part of their orbits between 0.983 and 1.3 astronomical units away from the Sun.[1] Some near-Earth asteroids' orbits intersect Earth's so they pose a collision danger.[2] Near-Earth asteroids are comparatively easy to access for spacecraft from Earth; in fact, some can be reached with much less fuel than it takes to reach the Moon.[3] This makes them an attractive target for exploration.[4] Two near-Earth asteroids have been visited by spacecraft: 433 Eros, by NASA's Near Earth Asteroid Rendezvous probe,[5] and 25143 Itokawa, by the JAXA Hayabusa mission.[6] Near-Earth asteroids are a sub-class of near-Earth object.

Contents |

Characteristics

Over 5,490 near-Earth asteroids are known, ranging in size up to ~32 kilometers (1036 Ganymed).[7][8] The number of near-Earth asteroids over one kilometer in diameter is estimated to be 500 - 1,000.[9][10] The composition of near-Earth asteroids is comparable to that of asteroids from the main asteroid belt, reflecting a variety of asteroid spectral types.[11]

NEAs only survive in their orbits for a few million years.[1] They are eventually eliminated by orbital decay and accretion by the Sun, collisions with the inner planets, or by being ejected from the solar system by near misses with the planets. With orbital lifetimes short compared to the age of the solar system, new asteroids must be constantly moved into near-Earth orbits to explain the observed asteroids. The accepted origin of these asteroids is that main belt asteroids are moved into the inner solar system through orbital resonances with Jupiter. The interaction with Jupiter through the resonance perturbs the asteroid's orbit and it comes into the inner solar system. The asteroid belt has gaps, known as Kirkwood gaps, where these resonances occur as the asteroids in these resonances have been moved onto other orbits. New asteroids migrate into these resonances due to the Yarkovsky effect which provides a continuing supply of near-Earth asteroids.[12]

NEA classification

A small fraction of near-Earth asteroids are extinct comets that have lost all their volatile constituents, and a few near-Earth asteroids still show faint comet-like tails. These near-Earth asteroids were probably derived from the Kuiper belt, a repository of comets residing beyond the orbit of Neptune. The rest of the near-Earth asteroids appear to be true asteroids, driven out of the asteroid belt by gravitational interactions with Jupiter.[1][13]

There are three families of near-Earth asteroids:[1]

- The Atens, which have average orbital radii closer than one astronomical unit (AU, the distance from the Earth to the Sun) and aphelia of greater than Earth's perihelion (0.983 AU), placing them usually inside the orbit of Earth.

- The Apollos, which have average orbital radii greater than that of the Earth and perihelia less than Earth's aphelion (1.017 AU).

- The Amors, which have average orbital radii in between the orbits of Earth and Mars and perihelia slightly outside Earth's orbit (1.017 - 1.3 AU). Amors often cross the orbit of Mars, but they do not cross the orbit of Earth.

Many Atens and all Apollos have orbits which cross that of the Earth, so they are a threat to impact the Earth on their current orbits. Amors do not cross the Earth's orbit and are not immediate impact threats, however their orbits may evolve into Earth-crossing orbits in the future.

Also sometimes used is the Arjuna asteroid classification for asteroids with extremely Earth-like orbits.[14]

The Near Earth Asteroid threat

Impact rate

Asteroids with diameters of 5-10m impact the Earth's atmosphere approximately once per year, with as much energy as the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, approximately 15 kilotonnes of TNT. These ordinarily explode in the upper atmosphere, and most or all of the solids are vaporized.[15] Objects of diameters of order 50 meters strike the Earth approximately once every thousand years, producing explosions comparable to the one observed at Tunguska in 1908.[16] Asteroids with a diameter of one kilometer hit the Earth an average of twice every million year interval.[1] Large collisions with five kilometer objects happen approximately once every ten million years.

Historic impacts

The general acceptance of the Alvarez hypothesis, explaining the Cretaceous–Tertiary extinction event as the result of a large asteroid or comet impact event, raised the awareness of the possibility of future Earth impacts with asteroids that cross the Earth's orbit.[16]

1908 Tunguska Event

On 30 June 1908 a stony asteroid exploded over Tunguska with the energy of the explosion of 10 megatons of TNT. The explosion occurred at a height of 8.5 kilometers. The asteroid which caused the explosion has been estimated to have had a diameter of 45-70 meters.[17]

2002 Eastern Mediterranean event

On June 6, 2002 an object with an estimated diameter of 10 meters collided with Earth. The collision occurred over the Mediterranean Sea, between Greece and Libya, at approximately 34°N 21°E and the object exploded in mid-air. The energy released was estimated (from infrasound measurements) to be equivalent to 26 kilotons of TNT, comparable to a small nuclear weapon.[18]

2008 Sudan event

On 5 October 2008, scientists calculated that a little Near-Earth asteroid 2008 TC3 just sighted that night should impact the Earth on 6 October over Sudan, at 0246 UTC, 5:46 a.m. local time.[19][20]. The asteroid arrived as predicted.[21][22]. This is the first time that an asteroid impact on Earth has been predicted before it occurred.

Near misses

On August 10, 1972 a meteor which became known as The Great Daylight 1972 Fireball was witnessed by many people moving north over the Rocky Mountains from the U.S. Southwest to Canada. It was an Earth-grazing meteoroid which passed within 57 kilometres (about 34 miles) of the Earth's surface. It was filmed by a tourist at the Grand Teton National Park in Wyoming with an 8-millimeter color movie camera. [23]

On March 23, 1989 the 300 meter (1,000-foot) diameter Apollo asteroid 4581 Asclepius (1989 FC) missed the Earth by 700,000 kilometers (400,000 miles) passing through the exact position where the Earth was only 6 hours before. If the asteroid had impacted it would have created the largest explosion in recorded history, thousands of times more powerful than the Tsar Bomba. It attracted widespread attention as early calculations had its passage being as close as 40,000 miles from the Earth, with large uncertainties that allowed for the possibility of it striking the Earth.[24]

On March 18, 2004, LINEAR announced a 30 meter asteroid 2004 FH which would pass the Earth that day at only 42,600 km (26,500 miles), about one-tenth the distance to the moon, and the closest miss ever noticed. They estimated that similar sized asteroids come as close about every two years.[25]

Future impacts

Although there have been a few false alarms, a number of asteroids are definitely known to be threats to the Earth. Asteroid (29075) 1950 DA was lost after its discovery in 1950 since not enough observations were made to allow plotting its orbit, and then rediscovered on December 31, 2000. The chance it will impact Earth on March 16, 2880 during its close approach has been estimated as 1 in 300. This chance of impact for such a large object is roughly 50% greater than that for all other such objects combined between now and 2880.[26] It has a diameter of about a kilometer.

Projects to minimize the threat

Astronomers have been conducting surveys to locate the NEAs. One of the best-known is the LINEAR which began in 1996. By 2004 LINEAR was discovering tens of thousands of objects each year and accounting for 65% of all new asteroid detections.[27] LINEAR uses two one-meter telescopes and one half-meter telescope based in New Mexico.[28]

Spacewatch, which uses a 90 centimeter telescope sited at the Kitt Peak Observatory in Arizona, updated with automatic pointing, imaging, and analysis equipment to search the skies for intruders, was set up in 1980 by Tom Gehrels and Dr. Robert S. McMillan of the Lunar and Planetary Laboratory of the University of Arizona in Tucson, and is now being operated by Dr. McMillan. The Spacewatch project has acquired a 1.8 meter telescope, also at Kitt Peak, to hunt for NEAs, and has provided the old 90 centimeter telescope with an improved electronic imaging system with much greater resolution, improving its search capability.[29]

Other near-earth asteroid tracking programs include Near-Earth Asteroid Tracking (NEAT), Lowell Observatory Near-Earth-Object Search (LONEOS), Catalina Sky Survey, Campo Imperatore Near-Earth Objects Survey (CINEOS), Japanese Spaceguard Association, and Asiago-DLR Asteroid Survey.[30]

"Spaceguard" is the name for these loosely affiliated programs, some of which receive NASA funding to meet a U.S. Congressional requirement to detect 90% of near-earth asteroids over 1 km diameter by 2008.[31] A 2003 NASA study of a follow-on program suggests spending US$250-450 million to detect 90% of all near-earth asteroids 140 meters and larger by 2028. [32]

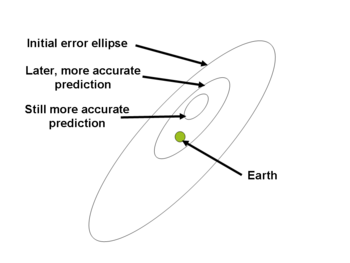

Asteroid impact predictions often make the news. The next few observations show an increasing chance of impact, but then further observations rule out any impact. The reason for this pattern is shown in the diagram at the right. The ellipses in this diagram show the likely asteroid position at closest earth approach. At first, with only a few asteroid observations, the error ellipse is very large and includes the Earth. This leads to a small, but non-zero, impact probability. Further observations shrink the error ellipse, but it still includes the Earth. This raises the impact probability, since the Earth now covers a larger fraction of the error region. Finally, yet more observations (often radar observations, or discovery of a previous sighting of the same asteroid on archival images) shrink the ellipse still further. Now the earth is outside the error region, and the impact probability returns to near zero.[33]

See also

- Asteroid deflection strategies

- Co-orbital moon

- List of NEAs by distance from Sun

- List of NEAs with record-setting close approaches to Earth

- Palermo Technical Impact Hazard Scale

- Quasi-satellite

- Sentry monitoring system

- Torino Scale

- Asteroid mining

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 1.3 1.4 A. Morbidelli, W. F. Bottke Jr., Ch. Froeschlé, P. Michel (January 2002). W. F. Bottke Jr., A. Cellino, P. Paolicchi, and R. P. Binzel. ed.. "Origin and Evolution of Near-Earth Objects" (PDF). Asteroids III (University of Arizona Press): 409–422. http://www.boulder.swri.edu/~bottke/Reprints/Morbidelli-etal_2002_AstIII_NEOs.pdf.

- ↑ Clark R. Chapman (May 2004). "The hazard of near-Earth asteroid impacts on earth". Earth and Planetary Science Letters 222 (1): 1–15. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2004E%26PSL.222....1C. Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Dan Vergano (February 2 2007). "Near-Earth asteroids could be 'steppingstones to Mars'", USA Today. Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Rui Xu, Pingyuan Cui, Dong Qiao and Enjie Luan (18 March 2007). "Design and optimization of trajectory to Near-Earth asteroid for sample return mission using gravity assists". Advances in Space Research 40 (2): 200–225. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2007AdSpR..40..220X. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Donald Savage and Michael Buckley (January 31, 2001). "NEAR Mission Completes Main Task, Now Will Go Where No Spacecraft Has Gone Before". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Don Yeomans (August 11, 2005). "Hayabusa's Contributions Toward Understanding the Earth's Neighborhood". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

- ↑ "Unusual Minor Planets". Minor Planet Center.

- ↑ Dr. David R. Williams (September 13 2006). "Near Earth Object Fact Sheet". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Jane Platt (January 12, 2000). "Asteroid Population Count Slashed". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

- ↑ David Rabinowitz, Eleanor Helin, Kenneth Lawrence and Steven Pravdo (13 January 2000). "A reduced estimate of the number of kilometre-sized near-Earth asteroids". Nature 403: 165–166. doi:. http://www.nature.com/nature/journal/v403/n6766/full/403165a0.html. Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

- ↑ D.F. Lupishko and T.A. Lupishko (May 2001). "On the Origins of Earth-Approaching Asteroids". Solar System Research 35 (3): 227–233. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2001SoSyR..35..227L. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ A. Morbidelli, D. Vokrouhlický (May 2003). "The Yarkovsky-driven origin of near-Earth asteroids". Icarus 163 (1): 120–134. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2003Icar..163..120M. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ D.F. Lupishko, M. di Martino and T.A. Lupishko (September 2000). "What the physical properties of near-Earth asteroids tell us about sources of their origin?". Kinematika i Fizika Nebesnykh Tel Supplimen (3): 213–216. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/2000KFNTS...3..213L.

- ↑ Ron Cowen (February 20 1993). "Near-Earth asteroids: class consciousness - new asteroids identified", Science News. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Clark R. Chapman & David Morrison (6 January 1994). "Impacts on the Earth by asteroids and comets: assessing the hazard". Nature 367: 33–40. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1994Natur.367...33C. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Richard Monastersky (March 1 1997). "The Call of Catastrophes". Science News Online. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Christopher F. Chyba, Paul J. Thomas & Kevin J. Zahnle (January 7 1993). "The 1908 Tunguska explosion: atmospheric disruption of a stony asteroid". Nature 361 (6407): 40–44. doi:. http://adsabs.harvard.edu/abs/1993Natur.361...40C. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ P. Brown, R.E. Spalding, D.O. ReVelle, E. Tagliaferri and S.P. Worden (21 November 2002). "The flux of small near-Earth objects colliding with the Earth" (PDF). Nature 420 (6913): 294–296. doi:. http://www.astro.uwo.ca/~pbrown/documents/flux-final.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Don Yeomans (October 6, 2008). "Small Asteroid Predicted to Cause Brilliant Fireball over Northern Sudan". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Richard A. Kerr (6 October 2008). "FLASH! Meteor to Explode Tonight". ScienceNOW Daily News. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Don Yeomans (October 7, 2008). "Impact of Asteroid 2008 TC3 Confirmed". NASA/JPL Near-Earth Object Program Office. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Richard A. Kerr (8 October 2008). "Asteroid Watchers Score a Hit". ScienceNOW Daily News. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Grand Teton Meteor Video, Youtube

- ↑ Brian G. Marsden (1998 March 29). "HOW THE ASTEROID STORY HIT: AN ASTRONOMER REVEALS HOW A DISCOVERY SPUN OUT OF CONTROL". The Boston Globe. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Steven R. Chesley and Paul W. Chodas (March 17, 2004). "Recently Discovered Near-Earth Asteroid Makes Record-breaking Approach to Earth". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ "Asteroid 1950 DA". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ Stokes, GStokes, G.; J. Evans (18 - 25 July, 2004). "Detection and discovery of near-earth asteroids by the linear program" in 35th COSPAR Scientific Assembly.: 4338. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ "Lincoln Near-Earth Asteroid Research (LINEAR)". National Aeronautics and Space Administration (23 October 2007).

- ↑ "The Spacewatch Project". Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ "Near-Earth Objects Search Program". National Aeronautics and Space Administration (23 October 2007).

- ↑ "NASA Releases Near-Earth Object Search Report". National Aeronautics and Space Administration. Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ David Morrison. "NASA NEO Workshop". National Aeronautics and Space Administration.

- ↑ "Why we have Asteroid “Scares”". Spaceguard UK.

External links

- JPL Near Earth Asteroid Tracking program (NEAT) (last updated May 2004)

- Near Earth Objects Dynamics Site

- Earth Impact Database

|

||||||||