Nauru

| Republic of Nauru

Ripublik Naoero

|

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

||||||

| Motto: "God's Will First" | ||||||

| Anthem: Nauru Bwiema |

||||||

|

||||||

| Capital | Yaren (de facto)1 | |||||

| Official languages | English, Nauruan | |||||

| Demonym | Nauruan /ˈnaʊruːən/ | |||||

| Government | Republic | |||||

| - | President | Marcus Stephen | ||||

| Independence | ||||||

| - | from the Australia, NZ, and UK-administered UN trusteeship. | 31 January 1968 | ||||

| Area | ||||||

| - | Total | 21 km2 (227th) 8.1 sq mi |

||||

| - | Water (%) | negligible | ||||

| Population | ||||||

| - | July 2008 estimate | 13,770 (212th) | ||||

| - | Density | 649/km2 (14th) 1,681/sq mi |

||||

| GDP (PPP) | 2006 estimate | |||||

| - | Total | $36.9 million (192nd) | ||||

| - | Per capita | $2,500 (2006 est.) (135th) | ||||

| HDI (2003) | n/a (unranked) (n/a) | |||||

| Currency | Australian dollar (AUD) |

|||||

| Time zone | (UTC+12) | |||||

| Drives on the | left | |||||

| Internet TLD | .nr | |||||

| Calling code | 674 | |||||

| 1 Yaren is the largest settlement and the seat of Parliament; it is often cited as capital, but Nauru does not have an officially designated capital. | ||||||

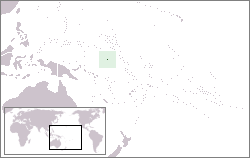

Nauru /nɑːˈuːruː/, officially the Republic of Nauru, is an island nation in the Micronesian South Pacific. The nearest neighbour is Banaba Island in the Republic of Kiribati, 300 km due east. Nauru is the world's smallest island nation, covering just 21 km² (8.1 sq. mi), the smallest independent republic, and the only republican state in the world without an official capital.[1] It is the least populous member of the United Nations.

Initially inhabited by Micronesian and Polynesian peoples, Nauru was annexed and designated a colony by Germany in the late 19th century, and became a mandate territory administered by Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom following World War I. The island was occupied by Japan during World War II, and after the war entered into trusteeship again. Nauru achieved independence in 1968.

Nauru is a phosphate rock island, and its primary economic activity since 1907 has been the export of phosphate mined from the island.[2] With the exhaustion of phosphate reserves, its environment severely degraded by mining, and the trust established to manage the island's wealth significantly reduced in value, the government of Nauru has resorted to unusual measures to obtain income. In the 1990s, Nauru briefly became a tax haven and money laundering center. Since 2001, it has accepted aid from the Australian government; in exchange for this aid, Nauru housed, until early 2008, an offshore detention centre that held and processed asylum seekers trying to enter Australia.[3]

Contents |

History

Nauru was first inhabited by Micronesian and Polynesian people at least 3,000 years ago. There were traditionally 12 clans or tribes on Nauru, which are represented in the 12-pointed star in the nation's flag. The Nauruan people called their island "Naoero"; the word "Nauru" was later derived so that English speakers could easily pronounce the name. Nauruans traced their descent on the female side. Naurans subsisted on coconut and pandanus fruit, and caught juvenile ibija fish, acclimatized them to fresh water conditions and raised them in Buada Lagoon, providing an additional reliable source of food.[4]

British Captain John Fearn, a whale hunter, became the first Westerner to visit the island in 1798, and named it Pleasant Island. From around the 1830s, Nauruans had contact with Europeans from whaling ships and traders who replenished their supplies at the island. Around this time, beachcombers and deserters began to live on the island. The islanders traded food for alcoholic toddy and firearms; the firearms were used during the 10-year war which began in 1878 and by 1888 had resulted in a reduction of the population from 1400 to 900 persons.

Colonial period

The island was annexed by Germany in 1888 and incorporated into Germany's Marshall Islands Protectorate; they called the island Nawodo or Onawero. The arrival of the Germans ended the war; social changes brought about by the war established Kings as rulers of the island, the most widely known being King Auweyida. Christian missionaries from the Gilbert Islands also arrived at the island in 1888.[5] The Germans ruled Nauru for almost 3 decades.

Phosphate was discovered on the island in 1900 by prospector Albert Ellis and the Pacific Phosphate Company started to exploit the reserves in 1906 by agreement with Germany; they exported their first shipment in 1907.[6] Following the outbreak of World War I, the island was captured by Australian forces in 1914. After the war, the League of Nations gave Australia a trustee mandate over Nauru; the UK and New Zealand were also co-trustees.[7][8] The three governments signed a Nauru Island Agreement in 1919, creating a board known as the British Phosphate Commission (BPC), which took over the rights to phosphate mining.

World War II

Japanese forces occupied the island on 26 August 1942.[9] The Japanese built an airfield on the island which was bombed in March 1943, preventing food supplies from reaching the island. The Japanese deported 1,200 Nauruans to work as labourers in the Chuuk islands, where 463 died.[10] The island was liberated on 13 September 1945 when the Australian warship HMAS Diamantina approached the island and Japanese forces surrendered. Arrangements were made by the BPC to repatriate Nauruans from Chuuk, and they were returned to Nauru by the BPC ship Trienza in January 1946.[11] In 1947, a trusteeship was approved by the United Nations, and Australia, NZ and the UK again became trustees of the island.

Independence

Nauru became self-governing in January 1966, and following a two-year constitutional convention, became independent in 1968, led by founding president Hammer DeRoburt. In 1967, the people of Nauru purchased the assets of the British Phosphate Commissioners, and in June 1970, control passed to the locally owned Nauru Phosphate Corporation. Income from the exploitation of phosphate gave Nauruans one of the highest living standards in the Pacific and per capita, in the world.[12] In 1989, the country took legal action against Australia in the International Court of Justice over Australia's actions during its administration of Nauru, in particular, Australia's failure to remedy the environmental damage caused by phosphate mining.[13] The action led to an out-of-court settlement to rehabilitate the mined-out areas of Nauru. Diminishing phosphate reserves has led to economic decline in Nauru, which has brought increasing political instability since the mid-1980s. Nauru had 17 changes of administration between 1989 and 2003.[14] Between 1999 and 2003, a series of no-confidence votes and elections resulted in two people, René Harris and Bernard Dowiyogo, leading the country for alternating periods. Dowiyogo died in office in March 2003 and Ludwig Scotty was elected President. Scotty was re-elected to serve a full term in October 2004. Following a vote of no confidence by Parliament against President Scotty on 19 December 2007, Marcus Stephen became president.

In recent times, a significant proportion of the country's income has been in the form of aid from Australia. In 2001, the MV Tampa, a Norwegian ship which had rescued 433[15] refugees (from various countries including Afghanistan) from a stranded 20-metre (65 ft) boat and was seeking to dock in Australia, was diverted to Nauru as part of the Pacific Solution. Nauru operated the detention centre in exchange for Australian aid. By November 2005, only two refugees, Mohammed Sagar and Muhammad Faisal, remained on Nauru from those first sent there in 2001,[16] with Sagar finally resettling in early 2007. The Australian government sent further groups of asylum seekers to Nauru in late 2006 and early 2007.[17] In late January 2008, following Australia's decision to close the processing centre, Nauru announced that they will request a new aid deal to ease the resulting blow to the economy.[18]

Politics

Nauru is a republic with a parliamentary system of government. The president is both the head of state and of government. An 18-member unicameral parliament is elected every three years. The parliament elects a president from its members, who appoints a cabinet of five to six members. Nauru does not have a formal structure for political parties; candidates typically stand as independents. 15 of the 18 members of the current parliament are independents, and alliances within the government are often formed on the basis of extended family ties.[14] Three parties that have been active in Nauruan politics are the Democratic Party, Nauru First and the Centre Party. The fact that Nauru is a democracy makes Nauru a rare and atypical counterexample of the traditional theory of the rentier state, as the sale of Nauru's natural resource has not led to authoritarianism.[19]

Since 1992, local government has been the responsibility of the Nauru Island Council (NIC). The NIC has limited powers and functions as an advisor to the national government on local matters. The role of the NIC is to concentrate its efforts on local activities relevant to Nauruans. An elected member of the Nauru Island Council cannot simultaneously be a member of parliament.[20] Land tenure in Nauru is unusual: all Nauruans have certain rights to all land on the island, which is owned by individuals and family groups; government and corporate entities do not own land and must enter into a lease arrangement with the landowners to use land. Non-Nauruans cannot own lands.[21]

Nauru has a complex legal system. The Supreme Court, headed by the Chief Justice, is paramount on constitutional issues. Other cases can be appealed to the two-judge Appellate Court. Parliament cannot overturn court decisions, but Appellate Court rulings can be appealed to the High Court of Australia;[22] in practice, this rarely happens. Lower courts consist of the District Court and the Family Court, both of which are headed by a Resident Magistrate, who also is the Registrar of the Supreme Court. Finally, there also are two quasi-courts: the Public Service Appeal Board and the Police Appeal Board, both of which are presided over by the Chief Justice.[23]

Nauru has no armed forces; under an informal agreement, defence is the responsibility of Australia. There is a small police force under civilian control.[1]

Districts

Nauru is divided into fourteen administrative districts which are grouped into eight electoral constituencies. The districts are:

|

|

Foreign relations

Following independence in 1968, Nauru joined the Commonwealth as a Special Member, and became a full member in 2000.[2] Nauru was admitted to the Asian Development Bank in 1991 and to the UN in 1999. It is a member of the Pacific Islands Forum, the South Pacific Regional Environmental Program, the South Pacific Commission, and the South Pacific Applied Geoscience Commission. The US Atmospheric Radiation Measurement Program operates a climate-monitoring facility on the island.

Nauru and Australia have close diplomatic ties. In addition to informal defense arrangements, the September 2005 Memorandum of Understanding between the two countries provides Nauru with financial aid and technical assistance, including a Secretary of Finance to prepare Nauru's budget, and advisers on health and education. This aid is in return for Nauru's housing of asylum seekers while their applications for entry into Australia are processed.[14] Nauru uses the Australian dollar as its official currency.

Nauru has used its position as a member of the UN to gain financial support from both Taiwan and the People's Republic of China by changing its position on the political status of Taiwan. During 2002, Nauru signed an agreement to establish diplomatic relations with the People's Republic of China on 21 July. This move followed China's promise to provide more than US$60 million in aid. In response, Taiwan severed diplomatic relations with Nauru two days later. Nauru later re-established links with Taiwan on 14 May 2005,[24] and diplomatic ties with China were officially severed on 31 May 2005; however, the PRC continues to maintain a diplomatic presence in the island nation.

Geography

Nauru is a small, oval-shaped island in the western Pacific Ocean, 42 km (26 mi.) south of the Equator. The island is surrounded by a coral reef, exposed at low tide and dotted with pinnacles. The reef is bound seaward by deep water, and inside by a sandy beach. The presence of the reef has prevented the establishment of a seaport, although sixteen artificial canals have been made in the reef to allow small boats to access the island. A 150–300 m (about 500–1000 ft.) wide fertile coastal strip lies landward from the beach. Coral cliffs surround the central plateau, which is known on the island as Topside. The highest point of the plateau called the Command Ridge is 71 m above sea level[25]. The only fertile areas are the narrow coastal belt, where coconut palms flourish. The land surrounding Buada Lagoon supports bananas, pineapples; vegetable, pandanus trees and indigenous hardwoods such as the tomano tree are cultivated. The population of the island is concentrated in the coastal belt and around Buada Lagoon.

Nauru was one of three great phosphate rock islands in the Pacific Ocean (the others are Banaba (Ocean Island) in Kiribati and Makatea in French Polynesia); however, the phosphate reserves are nearly depleted. Phosphate mining in the central plateau has left a barren terrain of jagged limestone pinnacles up to 15 m (49 ft) high. A century of mining has stripped and devastated four-fifths of the land area. Mining has also had an impact on the surrounding Exclusive Economic Zone with 40% of marine life considered to have been killed by silt and phosphate runoff.[26]

There are limited natural fresh water resources on Nauru. Roof storage tanks collect rainwater, but islanders are mostly dependent on a single, aging desalination plant. Nauru's climate is hot and extremely humid year-round, because of the proximity of the land to the Equator and the ocean. The island is affected by monsoonal rains between November and February. Annual rainfall is highly variable and influenced by the El Niño-Southern Oscillation, with several recorded droughts.[21] The temperature ranges between 26 and 35 °C (79 and 95 °F) during the day and between 25 and 28 °C (77 and 82 °F) at night. As an island nation, Nauru may be vulnerable to climate and sea level change, but to what degree is difficult to predict; at least 80% of the land area of Nauru is well elevated, but this area will be uninhabitable until the phosphate mining rehabilitation program is implemented.[26]

There are only sixty recorded vascular plant species native to the island, none of which are endemic. Coconut farming, mining and introduced species have caused serious disturbance to the native vegetation.[21] There are no native land mammals; there are native birds, including the endemic Nauru Reed Warbler, insects and land crabs. The Polynesian Rat, cats, dogs, pigs and chickens have been introduced to the island.

Economy

Nauru's economy depends almost entirely on declining phosphate deposits; there are few other resources, and most necessities are imported.[27] Small-scale mining is still conducted by the RONPhos, formerly known as the Nauru Phosphate Corporation. The government places a percentage of RONPhos' earnings in the Nauru Phosphate Royalties Trust. The Trust manages long-term investments, intended to support the citizens once the phosphate reserves have been exhausted. However, a history of bad investments, financial mismanagement, overspending and corruption has reduced the Trust's fixed and current assets, many of them were in Melbourne and many never fully recovered. Some of the failed investments included a loan to the Fitzroy Football Club which went into liquidation in 1996, the Queen Victoria Village site which was repossessed in 1999, while the Mercure Hotel in Sydney[28] and Nauru House in Melbourne were sold in 2004 to finance debts and Air Nauru's only Boeing 737-400 which was repossessed in December 2005 (though the aircraft was replaced in June of the next year with a Boeing 737-300 model, and normal service was resumed by the company).[29][30] The value of the Trust is estimated to have shrunk from A$1,300 million in 1991 to A$138 million in 2002.[31] Nauru currently lacks money to perform many of the basic functions of government (the national Bank of Nauru is insolvent). GDP per capita has fallen to only US$2,038, from its peak in the early 1980s of second in the world, only after the United Arab Emirates.[32]

There are no personal taxes in Nauru, and the government employs 95% of those Nauruans who work; unemployment is estimated to be 90%.[33][1] The Asian Development Bank notes that although the administration has a strong public mandate to implement economic reforms, in the absence of an alternative to phosphate mining, the medium-term outlook is for continued dependence on external assistance.[31] The sale of deep-sea fishing rights may generate some revenue. Tourism is not a major contributor to the economy, because there are few facilities for tourists; the Menen Hotel and OD-N-Aiwo Hotel are the only hotels on the island.

In the 1990s, Nauru became a tax haven and offered passports to foreign nationals for a fee. The inter-governmental Financial Action Task Force on Money Laundering (FATF) then identified Nauru as one of 15 "non-cooperative" countries in its fight against money laundering. During the 1990s, it was possible to establish a licensed bank in Nauru for $25,000, no questions asked. Under pressure from FATF, Nauru introduced anti-avoidance legislation in 2003, following which foreign hot money flew out of the country. In October 2005, this legislation—and its effective enforcement—led the FATF to lift the non-cooperative designation.[34]

From 2001 to 2007, the Nauru detention centre provided a source of income for the small country. The Nauruan authorities reacted with concern to its closure by Australia.[35] In February 2008, foreign affairs minister Dr. Kieren Keke stated that it would result in 100 Nauruans losing their jobs, and would affect 10% of the island's population directly or indirectly:

- "We have got a huge number of families that are suddenly going to be without any income. We are looking at ways we can try and provide some welfare assistance but our capacity to do that is very limited. Literally we have got a major unemployment crisis in front of us."[36]

Demographics

The island had 9265 residents at end 2006, and 96 percent speak Nauruan at home.[32] The population was previously higher but in 2006 some 1500 people left the island during a repatriation of immigrant workers from Kiribati and Tuvalu. The repatriation was motivated by widescale redundancies in the phosphate industry.[32] The official language of Nauru is Nauruan, a distinct Pacific island language. English is widely spoken and is the language of government and commerce.

The main religion practiced on the island is Christianity (two-thirds Protestant, one-third Roman Catholic). There is also a sizable Bahá'í population (10 percent of the population) and a Buddhist population (3%). The Constitution provides for freedom of religion; however, the government restricts this right in some circumstances, and has restricted the practice of religion by The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints and members of Jehovah's Witnesses, most of whom are foreign workers employed by RONPhos.[37]

Nauruans are statistically considered among the most obese people in the world, with 90% of adults having a higher BMI than the world average.[38] Nauru has the world's highest level of type 2 diabetes, with more than 40% of the population affected.[39] Other significant diet-related problems on Nauru include renal failure and heart disease. Life expectancy in 2006 was 58.0 years for males and 65.0 years for females.[40]

Literacy on the island is 96%, education is compulsory for children from six to 15 years of age (years 1–10), and two non-compulsory years are taught (Years 11 and 12).[41] There is a campus of the University of the South Pacific on the island; before the campus was built, students traveled to Australia for their university education.

Culture

Nauruans descended from Polynesian and Micronesian seafarers who believed in a female deity, Eijebong, and a spirit land, an island called Buitani. Two of the 12 original tribal groups became extinct in the 20th century. Angam Day, held on 26 October, celebrates the recovery of the Nauruan population after the two world wars, which together reduced the indigenous population to fewer than 1500. The displacement of the indigenous culture by colonial and contemporary, western influences is palpable. Few of the old customs have been preserved, but some forms of traditional music, arts and crafts, and fishing are still practiced.

There is no daily news publication, but there are several weekly or fortnightly publications, including the Bulletin, the Central Star News and The Nauru Chronicle. There is a state-owned television station, Nauru Television (NTV) which broadcasts programmes from New Zealand, and there is a state-owned non-commercial radio station, Radio Nauru, which carries items from Radio Australia and the BBC.[42]

Australian rules football is the most popular sport in Nauru; there is an elite national league with seven teams. All games are played at the island's only stadium, Linkbelt Oval. Other sports popular in Nauru include softball, cricket, golf, sailing, tennis, and soccer. Nauru participates in the Commonwealth and Summer Olympic Games, where it has been successful in weightlifting; Marcus Stephen has been a prominent medallist, who was elected to parliament in 2003, and was elected president of Nauru in 2007.

A traditional activity is catching noddy birds when they return from foraging at sea. At sunset, men stand on the beach ready to throw their lasso at the incoming birds. The Nauruan lasso is supple rope with a weight at the end. When a bird approaches, the lasso is thrown up, hits or drapes itself over the bird, and then falls to the ground. The captured noddies are cooked and eaten.[43]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 CIA World Fact Book URL accessed 2006-05-02.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 Republic of Nauru Permanent Mission to the United Nations URL Accessed 2006-05-10

- ↑ "Australia ends 'Pacific Solution'", BBC News (2008-02-08). Retrieved on 2008-08-05.

- ↑ McDaniel, C. N. and Gowdy, J. M. 2000. Paradise for Sale. University of California Press ISBN 0-520-22229-6 pp 13–28

- ↑ Ellis, A. F. 1935. Ocean Island and Nauru - their story. Angus and Robertson Limited. pp 29–39

- ↑ Ellis, A. F. 1935. Ocean Island and Nauru - their story. Angus and Robertson Limited. pp 127–139

- ↑ Cain, Timothy M., comp. "Nauru." The Book of Rule. 1st ed. 1 vols. New York: DK Inc., 2004.

- ↑ Agreement between Australia, New Zealand and United Kingdom regarding Nauru]

- ↑ Lundstrom, John B., The First Team and the Guadalcanal Campaign, Naval Institute Press, 1994, p. 175.

- ↑ Haden, J. D. 2000. Nauru: a middle ground in World War II Pacific Magazine URL Accessed 2006-05-05

- ↑ Garrett, J. 1996. Island Exiles. ABC. ISBN 0-7333-0485-0. pp176–181

- ↑ Nauru seeks to regain lost fortunes Nick Squires, 2008-03-15, BBC News Online. URL Accessed 2008-03-16

- ↑ Highet, K and Kahale, H. 1993. Certain Phosphate Lands in Nauru. The American Journal of International Law 87:282–288

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade. Republic of Nauru Country Brief - November 2005 URL accessed on 2006-05-02.

- ↑ The Bulletin publishes for the last time

- ↑ Gordon, M. 5 November 2005. Nauru's last two asylum seekers feel the pain. The Age URL Accessed 2006-05-08

- ↑ ABC News. 12 February 2007. Nauru detention centre costs $2m per month. ABC News Online URL Accessed 2007-02-12

- ↑ ABC News. 31 January 2008. Nauru wants aid deal after camp closure. ABC News Online URL Accessed 2008-01-31

- ↑ Kirkpatrick, Andrew. "Democracy and the Resource-Rich State: Towards a Sequential Theory of Rentierism" Paper presented at the annual meeting of The Midwest Political Science Association, Palmer House Hilton, Chicago, Illinois, 20 April 2006.

- ↑ Ogden, M.R. Republic of Nauru URL Accessed 2006-05-02.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 Nauru Department of Economic Development and Environment. 2003 First National Report To the United Nations Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD) URL Accessed 2006-05-03

- ↑ Nauru (High Court Appeals) Act (Australia) 1976. Australian Legal Information Institute URL Accessed 2006-08-07

- ↑ State Department Bureau of East Asian and Pacific Affairs September 2005 URL Accessed 2006-05-11

- ↑ AAP. 14 May 2005. Taiwan Re-establishes Diplomatic Ties with Nauru URL Accessed 2006-05-05

- ↑ (English) Republic of Nauru National Assessment Report

- ↑ 26.0 26.1 26.2 Republic of Nauru. 1999. Climate Change Response Under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change URL Accessed 2006-05-03

- ↑ Big tasks for a small island URL Accessed 2006-05-10

- ↑ http://www.smh.com.au/articles/2004/07/08/1089000294157.html

- ↑ Receivers take over Nauru House. The Age URL Accessed 2006-05-09

- ↑ Air Nauru flight Schedule URL Accessed 2006-05-02.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Asian Development Bank. 2005. Asian Development Outlook 2005 - Nauru URL Accessed 2006-05-02

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 [1]PDF (446 KiB)

- ↑ "Paradise well and truly lost", The Economist, 20 December 2001 [2] URL Accessed 2006-05-02.

- ↑ FATF. 13 October 2005. Nauru de-listed URL Accessed 2006-05-11

- ↑ "Nauru fears gap when camps close", Jewel Topsfield, The Age, 11 December 2007

- ↑ "Nauru 'hit' by detention centre closure", The Age, 7 February 2008

- ↑ US Department of State. 2003. International Religious Freedom Report 2003 - Nauru URL accessed 2005-05-02.

- ↑ Obesity in the Pacific: too big to ignore. 2002. Secretariat of the Pacific Community ISBN 982-203-925-5

- ↑ King, H. and Rewers M. 1993. Diabetes in adults is now a Third World problem. World Health Organization Ad Hoc Diabetes Reporting Group. Ethnicity & Disease 3:S67–74.

- ↑ WHO The world health report 2005. Nauru URL Accessed 2006-05-02

- ↑ Waqa, B. 1999. UNESCO Education for all Assessment Country report 1999 Country: Nauru URL Accessed 2006-05-02.

- ↑ BBC News. Country Profile: Nauru. URL Accessed 2006-05-02.

- ↑ Banaba/Ocean Island News. URL Accessed 2006-05-11.

- This article incorporates public domain text from the websites of the United States Department of State & CIA World Factbook.

External links

- Government

- General information

- Nauru entry at The World Factbook

- Nauru from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Nauru at the Open Directory Project

- Wikimedia Atlas of Nauru

- Travel

- Discover Nauru The Official Nauru Tourism Website

- Nauru travel guide from Wikitravel

- Our Airline - the former Air Nauru

- Our Airline Flight Schedule

- Other

- High resolution aerial views of Nauru on Google Maps

- Six Fivers

- Nauru country information on globalEDGE

- CenPac - The ISP of the Republic of Nauru

- Radio program "This American Life" featured a 30-minute story on Nauru

- Asian Development Bank Country Economic Report, Nauru, November, 2007

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||

|

||||||||