Musical theatre

Musical theatre is a form of theatre combining music, songs, spoken dialogue and dance. The emotional content of the piece – humor, pathos, love, anger – as well as the story itself, is communicated through the words, music, movement and technical aspects of the entertainment as an integrated whole. Since the early 20th century, musical theatre stage works have generally been called simply, "musicals".

Musicals are performed all around the world. They may be presented in large venues, such as big budget West End and Broadway theatre productions in London and New York City, or in smaller Fringe Theatre, Off-Broadway or regional productions, on tour, or by amateur groups in schools, theatres and other performance spaces. In addition to Britain and North America, there are vibrant musical theatre scenes in many countries in Europe, Latin America and Asia.

Some famous musicals include Show Boat, Oklahoma!, West Side Story, The Fantasticks, Hair, A Chorus Line, Les Misérables, The Phantom of the Opera, Rent, and The Producers.

Contents

|

Definitions

The three main components of a musical are the music, the lyrics, and the book. The book of a musical refers to the story of the show – in effect its spoken (not sung) lines; however, "book" can also refer to the dialogue and lyrics together, which are sometimes referred to (as in opera) as the libretto (Italian for “little book”). The music and lyrics together form the score of the musical. The interpretation of the musical by the creative team heavily influences the way that the musical is presented. The creative team includes a director, a musical director and usually a choreographer. A musical's production is also creatively characterized by technical aspects, such as set, costumes, stage properties, lighting, etc. that generally change from production to production (although some famous production aspects tend to be retained from the original production, for example, Bob Fosse's choregraphy in Chicago). The 20th century "book musical" has been defined as a musical play where the songs and dances are fully integrated into a well-made story, with serious dramatic goals, that is able to evoke genuine emotions other than laughter.[2]

There is no fixed length for a musical, and it can range from a short one-act entertainment to several acts and several hours in length (or even a multi-evening presentation); however, most musicals range from one and a half hours to three hours. Musicals today are typically presented in two acts, with one intermission ten to 20 minutes in length. The first act is almost always somewhat longer than the second act, and generally introduces most of the music. A musical may be built around four to six main theme tunes that are reprised throughout the show, or consist of a series of songs not directly musically related. Spoken dialogue is generally interspersed between musical numbers, although the use of "sung dialogue" or recitative is not unknown, especially in so-called "sung-through" musicals such as Les Misérables and Evita.

Musical theatre is closely related to another theatrical performance art, opera. These forms are usually distinguished by weighing a number of factors. Musicals generally have a greater focus on spoken dialogue (though some musicals are entirely accompanied and sung through, such as Jesus Christ Superstar and Les Misérables; and on the other hand some operas, such as Die Zauberflöte, and most operettas, have some unaccompanied dialogue), on dancing (particularly by the principal performers as well as the chorus), on the use of various genres of popular music (or at least popular singing styles), and on the avoidance of certain operatic conventions. In particular, a musical is almost never performed in any but the language of its audience. Musicals produced in London or New York, for instance, are invariably sung in English, even if they were originally written in another language (again, Les Misérables, originally written in French, is a good example).

While an opera singer is primarily a singer and only secondarily an actor (and rarely needs to dance at all), a musical theatre performer is usually an actor first and then a singer and dancer. Someone who is equally accomplished at all three is referred to as a "triple threat". Composers of music for musicals often consider the vocal demands of roles with musical theatre performers in mind, and theatres staging musicals generally use amplification of the actors' singing voices in a way that would normally be disapproved of in an operatic context. Some works (e.g. by Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim) have received both "musical theatre" and "operatic" productions. Similarly, some older operettas or light operas (such as The Pirates of Penzance by Gilbert and Sullivan) have had modern productions or adaptations that treat them as musicals. Sondheim said: "I really think that when something plays Broadway it's a musical, and when it plays in an opera house it's opera. That's it. It's the terrain, the countryside, the expectations of the audience that make it one thing or another."[3]

This article primarily concerns musical theatre works that are distinctively "non-operatic", but there inescapably remains some overlap between lighter operatic forms and the more musically complex or ambitious musicals: a grey area, in which production styles are almost as important as actual musical or dramatic content in defining into which art form the piece falls. In isolation, at least, none of these features is truly "defining", and in practice it is often difficult to distinguish among the various kinds of light musical theatre, including "operetta", "comic opera", "light opera", "burletta", "musical play", "musical comedy", "extravaganza", "burlesque", "music hall" and "revue".

A "book" musical's moments of greatest dramatic intensity are often performed in song. Proverbially, "when the emotion becomes too strong for speech (or recitative) you sing; when it becomes too strong for song, you dance." A song is ideally crafted to suit the character (or characters) and their situation within the story; although there have been times in the history of the musical (e.g. the 1890s and 1920s) when this integration between music and story has been tenuous. As New York Times critic Ben Brantley described the ideal of song in theatre in reviewing the 2008 revival of Gypsy, "There is no separation at all between song and character, which is what happens in those uncommon moments when musicals reach upward to achieve their ideal reasons to be."[4]

A musical often opens with a song that sets the tone of the show, introduces some or all of the major characters, and shows the setting of the play. Within the compressed nature of the musical, the writers must develop the characters and the plot. Music provides a means to express emotion. However, typically, many fewer words are sung in a five-minute song than are spoken in a five-minute block of dialogue. Therefore there is less time to develop drama than in a straight play of equivalent length, since a musical usually devotes more time to music than to dialogue.

The material for musicals is often original, but many musicals are adapted from novels (Wicked and Man of La Mancha), plays (Hello, Dolly!), classic legends (Camelot), historical events (Evita) or films (The Producers and Hairspray). On the other hand, many familiar musical theatre works have been the basis for musical films, such as The Sound of Music, West Side Story, My Fair Lady, Beauty and the Beast and Chicago. India produces numerous musical films, referred to as "Bollywood" musicals, and Japan produces Anime-style musicals. Another recent genre of musicals, called "jukebox musicals" (Mamma Mia!), weaves songs written by (or introduced by) a popular artist or group into a story – sometimes based on the life or career of the person/group in question.

History

Ancient Greece and middle ages

Musical theatre in Europe dates back to the theatre of the ancient Greeks, who included music and dance in their stage comedies and tragedies in the 5th century BCE[5] The dramatists Aeschylus and Sophocles composed their own music to accompany their plays and choreographed the dances of the chorus. The 3rd-century BCE Roman comedies of Plautus included song and dance routines performed with orchestrations. The Romans introduced technical innovations. For example, to make the dance steps more audible in large open air theatres, Roman actors attached metal chips called "sabilla" to their stage footwear – the first tap shoes.[6] By the Middle Ages, theatre in Europe consisted mostly of traveling minstrels and small performing troupes of performers singing and offering slapstick comedy.[7] In the 12th and 13th centuries, religious dramas, such as The Play of Herod and The Play of Daniel taught the liturgy, set to church chants. Later "Mystery plays" were created that told a biblical story in a sequence of entertaining parts. Several pageant wagons (stages on wheels) would move about the city, and a group of actors would tell their part of the story. Once finished, the group would move on with their wagon, and the next group would arrive to tell its part of the story. These plays developed into an autonomous form of musical theatre, with poetic forms sometimes alternating with the prose dialogues and liturgical chants. The poetry was provided with modified or completely new melodies.[8]

Renaissance to the 1700s

The Renaissance saw these forms evolve into commedia dell'arte, an Italian tradition where raucous clowns improvised their way through familiar stories, and from there, opera buffa. Molière turned several of his farcical comedies into musical entertainments with songs (music provided by Jean Baptiste Lully) and dance in the late 1600s. Arts of all kinds became widely popular, including musical theatre.[5]

By the 1700s, two forms of musical theatre were popular in Britain, France and Germany: ballad operas, like John Gay's The Beggar's Opera (1728), that included lyrics written to the tunes of popular songs of the day (often spoofing opera), and comic operas, with original scores and mostly romantic plot lines, like Michael Balfe's The Bohemian Girl (1845). Other musical theatre forms developed by the 19th century, such as vaudeville, British music hall, melodrama and burlesque. Melodramas and burlettas, in particular, were popularized partly because most London theatres were licensed only as music halls and not allowed to present plays without music. In any event, what a piece was called did not necessarily define what it was. The Broadway extravaganza The Magic Deer (1852) advertised itself as "A Serio Comico Tragico Operatical Historical Extravaganzical Burletical Tale of Enchantment."[7]

The first recorded long running play of any kind was The Beggar's Opera, which ran for 62 successive performances in 1728. It would take almost a century before the first play broke 100 performances, with Tom and Jerry, based on the book Life in London (1821), and the record soon reached 150 in the late 1820s.[9]

New York (and so, America) did not have a significant theatre presence until 1752, when William Hallam sent a company of twelve actors to the colonies with his brother Lewis as their manager. They established a theatre in Williamsburg, Virginia and opened with The Merchant of Venice and The Anatomist. The company moved to New York in the summer of 1753, performing ballad-operas such as The Beggar’s Opera and ballad-farces like Damon and Phillida. By the 1840s, P.T. Barnum was operating an entertainment complex in lower Manhattan (theatre in New York moved from downtown gradually to midtown beginning around 1850, seeking less expensive real estate prices, and did not arrive in the Times Square area until the 1920s and 1930s). Broadway's first "long-run" musical was a 50 performance hit called The Elves in 1857. New York runs continued to lag far behind those in London, but Laura Keene's "musical burletta" Seven Sisters (1860) shattered previous New York records with a run of 253 performances.

Development of musical comedy

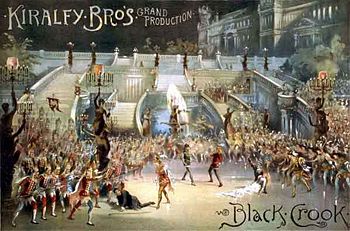

The first theatre piece that conforms to the modern conception of a musical, adding dance and original music that helped to tell the story, is generally considered to be The Black Crook, which premiered in New York on September 12, 1866. The production was a staggering five-and-a-half hours long, but despite its length, it ran for a record-breaking 474 performances. The same year, The Black Domino/Between You, Me and the Post was the first show to call itself a "musical comedy."[1] At that time, in England, musical theatre consisted of mostly of music hall, adaptations of risque French operetta and burlesques, notably at the Gaiety Theatre beginning in 1868. In reaction to these a few family-friendly entertainments were created, such as the German Reed Entertainments.

Comedians Edward Harrigan and Tony Hart produced and starred in musicals on Broadway between 1878 (The Mulligan Guard Picnic) and 1885, with book and lyrics by Harrigan and music by his father-in-law David Braham. These musical comedies featured characters and situations taken from the everyday life of New York's lower classes and represented a significant step forward from vaudeville and burlesque, towards a more literate form. They starred high quality singers (Lillian Russell, Vivienne Segal, and Fay Templeton) instead of the ladies of questionable repute who had starred in earlier musical forms.

The length of runs in the theatre changed rapidly around the same time that the modern musical was born. As transportation improved, poverty in London and New York diminished, and street lighting made for safer travel at night, the number of potential patrons for the growing number of theatres increased enormously. Plays could run longer and still draw in the audiences, leading to better profits and improved production values. The first play to achieve 500 consecutive performances was the London (non-musical) comedy Our Boys, opening in 1875, which set an astonishing new record of 1,362 performances.[10]

This run was not equalled on the musical stage until World War I, but musical theatre soon broke the 500 performance mark London, most notably by the series of more than a dozen long-running Gilbert and Sullivan family-friendly comic opera hits, including H.M.S. Pinafore in 1878 and The Mikado in 1885,[11] whose runs were exceeded by Alfred Cellier and B. C. Stephenson's record-breaking 1886 hit, Dorothy (a show midway between comic opera and musical comedy), with 931 performances, which was chased (but not equalled) by several of the most successful London musicals of the 1890s. Other British composers of the period included Edward Solomon and F. Osmond Carr. The most popular of these shows also enjoyed profitable New York productions and tours of Britain, America, Europe, Australasia and South Africa. These shows were fare for "respectable" audiences, a marked contrast from the risqué burlesques, melodramas, bawdy music hall shows and badly translated French operettas that dominated the stage earlier in the 19th century and drew a sometimes seedy crowd looking for easy entertainment.

Charles Hoyt's A Trip to Chinatown (1891) was Broadway's long-run champion (until Irene in 1919), running for 657 performances. Gilbert and Sullivan's comic operas were both pirated and imitated in New York by productions such as Reginald DeKoven's Robin Hood (1891) and John Philip Sousa's El Capitan (1896). A Trip to Coontown (1898) was the first musical comedy entirely produced and performed by African Americans in a Broadway theatre (largely inspired by the routines of the minstrel shows), followed by the ragtime-tinged Clorindy the Origin of the Cakewalk (1898), and the highly successful In Dahomey (1902). Hundreds of musical comedies were staged on Broadway in the 1890s and early 1900s comprised of songs written in New York's Tin Pan Alley involving composers such as Gus Edwards, John Walter Bratton, and George M. Cohan (Little Johnny Jones (1904), 45 Minutes From Broadway (1906), and George Washington Jr. (1906)). Still, New York runs continued to be relatively short, with a few exceptions, compared with London runs, until World War I.[12]

Meanwhile, musicals had spread to the London stage by the Gay Nineties. George Edwardes had left the management of Richard D'Oyly Carte's Savoy Theatre. He took over the Gaiety Theatre and, at first, he improved the quality of the old Gaiety Theatre burlesques. He perceived that theatregoers wanted a new alternative to the Savoy-style comic operas and their intellectual, political, absurdist satire. He experimented with a modern-dress, family-friendly musical theatre style, with breezy, popular songs, snappy, romantic banter, and stylish spectacle at the Gaiety, Daly's Theatre and other venues. These drew on the the traditions of comic opera and also used elements of burlesque and of the Harrigan and Hart pieces. He replaced the bawdy women of burlesque with his "respectable" corps of dancing, singing Gaiety Girls to complete the musical and visual fun. The success of the first of these, In Town in 1892 and A Gaiety Girl in 1893, confirmed Edwardes on the path he was taking. These "musical comedies", as he called them, revolutionized the London stage and set the tone for the next three decades.

Edwardes' early Gaiety hits included a series of light, romantic "poor maiden loves aristocrat and wins him against all odds" shows, usually with the word "Girl" in the title, including The Shop Girl (1894) and A Runaway Girl (1898), with music by Ivan Caryll and Lionel Monckton. These shows were immediately widely copied at other London theatres (and soon in America), and the Edwardian musical comedy swept away the earlier musical forms of comic opera and operetta. At Daly's Theatre, Edwardes presented slightly more complex comedy hits. The Geisha (1896) by Sidney Jones with lyrics by Harry Greenbank and Adrian Ross and then Jones' San Toy (1899) each ran for more than two years and also found great international success.

The British musical comedy Florodora (1899) by Leslie Stuart and Paul Rubens made a splash on both sides of the Atlantic, as did A Chinese Honeymoon (1901), by British lyricist George Dance and American-born composer Howard Talbot, which ran for a record setting 1,074 performances in London and 376 in New York. The story concerns couples who honeymoon in China and inadvertently break the kissing laws (shades of The Mikado). The Belle of New York (1898) ran for 697 performances in London after a brief New York run, becoming the first American musical to run for over a year in London. After the turn of the century, Seymour Hicks (who joined forces with American producer Charles Frohman) wrote popular shows with composer Charles Taylor and others, and Edwardes and Ross continued to churn out hits like The Toreador (1901), A Country Girl, The Orchid (1903), The Girls of Gottenberg (1907) and Our Miss Gibbs (1909). Other Edwardian musical comedy hits included The Arcadians (1909) and The Quaker Girl (1910).

Operetta and World War I

Probably the best known composers of operetta, beginning in the second half of the 19th century, were Jacques Offenbach and Johann Strauss II (usually played in bad, bawdy translations in London and New York). In England in the 1870s and 1880s, W. S. Gilbert and Arthur Sullivan created a family-friendly alternative to French operetta, styled British comic opera. Although British and American musicals of the 1890s and the first few years of the 20th century had virtually swept operetta and comic opera from the stage, operettas returned to the London and Broadway stages in 1907 with The Merry Widow, and operettas and musicals became direct competitors for a while.

In the early years of the 20th century, English-language adaptations of 19th century continental operettas, as well as operettas by a new generation of European composers, such as Franz Lehár and Oscar Straus, among others, spread throughout the English-speaking world. and Victor Herbert, whose work included some intimate musical plays with modern settings as well as his string of famous operettas (The Fortune Teller (1898), Babes in Toyland (1903), Mlle. Modiste (1905), The Red Mill (1906), and Naughty Marietta (1910)). These operetta composers were joined by British and American composers and librettists of the 1910s, including P. G. Wodehouse, Guy Bolton and Harry B. Smith (the "Princess Theatre" shows), who paved the way for Jerome Kern's later work by showing that a musical could combine a light popular touch with real continuity between story and musical numbers. These owed much to Gilbert and Sullivan and the composers of the 1890s.[13]

The winner of this competition between operetta and musicals was the theatre-going public, who needed escapist entertainment during the dark times of World War I and flocked to theatres for musical theatre hits like Maid of the Mountains, Irene,[14] and especially Chu Chin Chow (whose run of 2,238 performances, more than twice as many as any previous musical, set a record that stood for nearly forty years until Salad Days) as well as popular revues like The Bing Boys Are Here. The legacy of the operetta composers served as an inspiration to the next generation of composers of operettas and musicals in the 1920s and 1930s, such as Rudolf Friml, Irving Berlin, Sigmund Romberg, George Gershwin, and Noel Coward, and these, in turn, influenced Rodgers, Sondheim, and many others later in the century.[7]

At the same time, the primacy of British musical theatre in the late 19th century faded and was gradually replaced by American innovation through the first decades of the 20th century, as George M. Cohan filled the theatres with lively musical entertainments, the Tin Pan Alley composers began to produce international hits, new musical styles such as ragtime and jazz were created, and the Shubert Brothers began to take control of the Broadway theatres. Critic Andrew Lamb notes, "The triumph of American works over European in the first decades of the twentieth century came about against a changing social background. The operatic and theatrical styles of nineteenth-century social structures were replaced by a musical style more aptly suited to twentieth-century society and its vernacular idiom. It was from America that the more direct style emerged, and in America that it was able to flourish in a developing society less hidebound by nineteenth-century tradition."[15]

The Roaring Twenties

The motion picture mounted a challenge to the stage. At first, films were silent and presented only a limited challenge to theatre. But by the end of the 1920s, films like The Jazz Singer could be presented with synchronized sound, and critics wondered if the cinema would replace live theatre altogether. The musicals of the Roaring Twenties, borrowing from vaudeville, music hall and other light entertainments, tended to ignore plot in favor of emphasizing star actors and actresses, big dance routines, and popular songs. Throughout the first half of the twentieth century, popular music was dominated by theatre writers. Many shows were revues with little plot. For instance, Florenz Ziegfeld produced annual spectacular song-and-dance revues on Broadway featuring extravagant sets and elaborate costumes, but there was little to tie the various numbers together. In London, the Aldwych Farces were similarly successful, and stars such as Ivor Novello were popular. These spectacles also raised production values, and mounting a musical generally became more expensive.

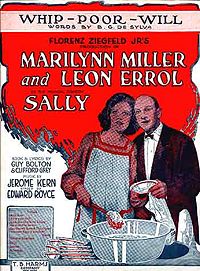

Typical of the decade were lighthearted productions like Sally; Lady Be Good; Sunny; No, No, Nanette; Oh, Kay!; and Funny Face. Their books may have been forgettable, but they produced enduring standards from George Gershwin, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Vincent Youmans, and Richard Rodgers and Lorenz Hart, among others, and stars like Marilyn Miller and Fred Astaire. Audiences tapped their toes to these musicals on both sides of the Atlantic ocean while continuing to patronize the popular operettas that were continuing to come out of continental Europe and also from composers like Noel Coward in London and Sigmund Romberg and Rudolf Friml in America. Clearly, cinema had not killed live theatre.

Leaving these comparatively frivolous entertainments behind, and taking the drama a giant step beyond Victor Herbert and sentimental operetta, Show Boat, which premiered on December 27, 1927 at the Ziegfeld Theatre in New York, represented a far more complete integration of book and score, with dramatic themes, as told through the music, dialogue, setting and movement, woven together more seamlessly than in previous musicals. Show Boat, with a book and lyrics adapted from Edna Ferber's novel by Oscar Hammerstein II and P. G. Wodehouse, and music by Jerome Kern, presented a new concept that was embraced by audiences immediately. "Here we come to a completely new genre – the musical play as distinguished from musical comedy. Now... the play was the thing, and everything else was subservient to that play. Now... came complete integration of song, humor and production numbers into a single and inextricable artistic entity."[16] Despite some of its startling themes—miscegenation among them—the original production ran a total of 572 (or 575, depending on the source) performances. Still, Broadway runs lagged behind London's in general. By way of comparison, in 1920, The Beggar's Opera began an astonishing run of 1,463 performances at the Lyric Theatre in Hammersmith, England.

1930s

The Great Depression affected theatre audiences on both sides of the Atlantic, as people had little money to spend on entertainment. In addition, "talkie" films at low prices presented a strong challenge to theatre of all kinds. Only a few shows exceeded a run on Broadway or in London of 500 performances. Still, for those who could afford it, this was an exciting time in the development of musical theatre. Encouraged by the success of Show Boat, creative teams began following the "format" of that popular hit. Of Thee I Sing (1931), a political satire with music by George Gershwin and lyrics by Ira Gershwin and Morrie Ryskind, was the first musical to be awarded the Pulitzer Prize. The Band Wagon (1931), starred dancing partners Fred Astaire and his sister Adele. Porter's Anything Goes (1934) affirmed Ethel Merman's position as the First Lady of musical theatre – a title she maintained for many years. As Thousands Cheer (1933) was an Irving Berlin and Moss Hart success that marked Marilyn Miller's last show and the first Broadway show to star an African-American, Ethel Waters).[17]

Gershwin's Porgy and Bess (1935) was a step closer to opera than Show Boat and the other musicals of the era, and in some respects it foreshadowed such "operatic" musicals as West Side Story and Sweeney Todd. The Cradle Will Rock (1937), with a book and score by Marc Blitzstein and directed by Orson Welles, was a highly political piece that, despite the controversy surrounding it, managed to run for 108 performances. Kurt Weill's Knickerbocker Holiday brought to the musical stage New York City's early history, using as its source writings by Washington Irving, while good-naturedly satirizing the good intentions of President Franklin D. Roosevelt.

British writers such as Noel Coward and Ivor Novello continued to deliver old fashioned, sentimential musicals, such as The Dancing Years. Similarly, Rodgers & Hart returned from Hollywood to churn out a series of lighthearted Broadway hits, including On Your Toes (1936, with Ray Bolger, the first Broadway musical to make dramatic use of classical dance), Babes In Arms (1937), I'd Rather Be Right, a political satire with George M. Cohan as President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and The Boys From Syracuse (1938), and Cole Porter wrote a similar string of hits, including Anything Goes (1934) and DuBarry Was a Lady (1939). He later would go on to write scores for such classics as Can-Can (1953) and Silk Stockings (1955). But the longest running piece of musical theatre of the 1930s was Hellzapoppin (1938), a revue with audience participation, which played for 1,404 performances, setting a new Broadway record that was finally beaten by Oklahoma!

Despite the economic woes and the competition from film, the musical survived. In fact, the move towards political satire in Of Thee I Sing, I'd Rather Be Right and Knickerbocker Holiday, together with the musical sophistication of the Gershwin, Kern, Rodgers and Weill musicals and the fast-paced staging and naturalistic dialogue style created by director George Abbott showed that musical theatre was finally evolving beyond the gags and showgirls musicals of the Gay Nineties and Roaring Twenties and the sentimental romance of operetta.

The Golden Age (1943 to 1968)

The Golden Age of the Broadway musical is generally considered to have begun with Oklahoma! (1943) and to have ended with Hair (1968).

1940s

The 1940s would begin with more hits from Porter, Irving Berlin, Rodgers and Hart, Weill and Gershwin, some with runs over 500 performances as the economy rebounded, but artistic change was in the air.

Rodgers and Hammerstein's Oklahoma! completed the revolution begun by Show Boat, by tightly integrating all the aspects of musical theatre, with a cohesive plot, songs that furthered the action of the story, and featured dream ballets and other dances that advanced the plot and developed the characters, rather than using dance as an excuse to parade scantily-clad women across the stage. Rodgers and Hammerstein hired ballet choreographer Agnes de Mille, who used everyday motions to help the characters express their ideas. It defied musical conventions by raising its first act curtain not on a bevy of chorus girls, but rather on a woman churning butter, with an off-stage voice singing the opening lines of Oh, What a Beautiful Mornin'. It was the first "blockbuster" Broadway show, running a total of 2,212 performances, and was made into a hit film. It remains one of the most frequently produced of the team's projects. William A. Everett and Paul R. Laird wrote that this was a "show, that, like Show Boat, became a milestone, so that later historians writing about important moments in twentieth-century theatre would begin to identify eras according to their relationship to Oklahoma!"[18]

"After Oklahoma!, Rodgers and Hammerstein were the most important contributors to the musical-play form.... The examples they set in creating vital plays, often rich with social thought, provided the necessary encouragement for other gifted writers to create musical plays of their own".[16] The two collaborators created an extraordinary collection of some of musical theatre's best loved and most enduring classics, including Carousel (1945), South Pacific (1949), The King and I (1951), and The Sound of Music (1959). Some of these musicals, including Oklahoma!, Carousel, South Pacific and The King and I, treat more serious subject matter than most earlier shows: the villain in Oklahoma! is a suspected murderer and psychopath with a fondness for lewd post cards; Carousel deals with spousal abuse, thievery, suicide and the afterlife; South Pacific explores miscegenation even more thoroughly than Show Boat; and the hero of The King and I dies onstage.

Americana was displayed on Broadway during the "Golden Age", as the wartime cycle of shows began to arrive. An example of this is On the Town (1944), written by Betty Comden and Adolph Green, composed by Leonard Bernstein and choreographed by Jerome Robbins. The musical is set during wartime, where a group of three sailors are on a 24 hour shore leave in New York. During their day, they each meet a wonderful woman. The women in this show have a specific power to them, as if saying, "Come here! I need a man!" The show also gives the impression of a country with an uncertain future, as the sailors also have with their women before leaving.

Oklahoma! inspired others to continue the trend. Irving Berlin used sharpshooter Annie Oakley's career as a basis for his Annie Get Your Gun (1946, 1,147 performances); Burton Lane, E. Y. Harburg, and Fred Saidy combined political satire with Irish whimsy for their fantasy Finian's Rainbow (1947, 1,725 performances); and Cole Porter found inspiration in William Shakespeare's Taming of the Shrew for Kiss Me, Kate (1948, 1,077 performances). The American musicals overwhelmed the old-fashioned British Coward/Novello-style shows, one of the last big successes of which was Novello's Perchance to Dream (1945, 1,021 performances).

1950s

Damon Runyon's eclectic characters were at the core of Frank Loesser's and Abe Burrows' Guys and Dolls, (1950, 1,200 performances); and the Gold Rush was the setting for Alan Jay Lerner and Frederick Loewe's Paint Your Wagon (1951). The relatively brief seven-month run of that show didn't discourage Lerner and Loewe from collaborating again, this time on My Fair Lady (1956), an adaptation of George Bernard Shaw's Pygmalion starring Rex Harrison and Julie Andrews, which at 2,717 performances held the long-run record for many years. Popular Hollywood movies were made of all of these musicals. The Boy Friend (1954) ran for 2,078 performances in London, briefly becoming the third-longest running musical in West End or Broadway history (after Chu Chin Chow and Oklahoma!), until it was demoted by Salad Days. It marked Julie Andrews' American debut. Another record was set by The Threepenny Opera, which ran for 2,707 performances, becoming the longest-running off-Broadway musical until The Fantasticks. The production also broke ground by showing that musicals could be profitable off-Broadway in a small-scale, small orchestra format. This was confirmed in 1959 when a revival of Jerome Kern and P. G. Wodehouse's Leave it to Jane ran for more than two years. The 1959-1960 Off-Broadway season included a dozen musicals and revues including Little Mary Sunshine, The Fantasticks and Ernest in Love, a musicalization of Oscar Wilde's 1895 hit The Importance of Being Earnest.[19]

As in Oklahoma!, dance was an integral part of West Side Story (1957), which transported Romeo and Juliet to modern day New York City and converted the feuding Montague and Capulet families into opposing ethnic gangs, the Jets and the Sharks. The book was adapted by Arthur Laurents, with music by Leonard Bernstein and lyrics by newcomer Stephen Sondheim. It was embraced by the critics but failed to be a popular choice for the "blue-haired matinee ladies," who preferred the small town River City, Iowa of Meredith Willson's The Music Man to the alleys of Manhattan's Upper West Side. Apparently Tony Award voters were of a similar mind, since they favored the former over the latter. West Side Story had a respectable run of 732 performances (1,040 in the West End), while The Music Man ran nearly twice as long, with 1,375 performances. However, the film of West Side Story was extremely successful.

Laurents and Sondheim teamed up again for Gypsy (1959, 702 performances), with Jule Styne providing the music for a backstage story about the most driven stage mother of all-time, stripper Gypsy Rose Lee's mother Rose. The original production ran for 702 performances, and was given four subsequent revivals, with Angela Lansbury, Tyne Daly, Bernadette Peters and Patti LuPone later tackling the role made famous by Ethel Merman.

Automotive companies and other types of corporations began to hire Broadway talent to write corporate musicals, private shows which were only seen by their employees or customers. The 1950s ended with Rodgers and Hammerstein's last hit, The Sound of Music, which also became another hit for Mary Martin. It ran for 1,443 performances and shared the Tony Award for Best Musical. Together with its extremely successful 1965 film version, it has become one of the most popular musicals in history.

1960s

In 1960, The Fantasticks was first produced off-Broadway. This intimate allegorical show would quietly run for over 40 years at the Sullivan Street Theatre in Greenwich Village, becoming by far the longest-running musical in history. Its authors produced other innovative works in the 1960s, such as Celebration and I Do! I Do!, the first two-character Broadway musical. The 1960s would see a number of blockbusters, like Fiddler on the Roof (1964; 3,242 performances), Hello, Dolly! (1964; 2,844 performances), Funny Girl (1964; 1,348 performances), and Man of La Mancha (1965; 2,328 performances), and some more risqué pieces like Cabaret, before ending with the emergence of the rock musical. Two men had considerable impact on musical theatre history beginning in this decade, Stephen Sondheim and Jerry Herman.

The first project for which Sondheim wrote both music and lyrics was A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (1962, 964 performances), with a book based on the works of Plautus by Burt Shevelove and Larry Gelbart, and starring Zero Mostel. Sondheim moved the musical beyond its concentration on the romantic plots typical of earlier eras; his work tended to be darker, exploring the grittier sides of life both present and past. Some of his earlier works include Anyone Can Whistle (1964, which—at a mere nine performances, despite having star power in Lee Remick and Angela Lansbury—is an infamous flop), Company (1970), Follies (1971), and A Little Night Music (1973). He has found inspiration in the unlikeliest of sources—the opening of Japan to Western trade for Pacific Overtures, a legendary murderous barber seeking revenge in the Industrial Age of London for Sweeney Todd, the paintings of Georges Seurat for Sunday in the Park with George, fairy tales for Into the Woods, and a collection of individuals intent on eliminating the President of the United States in Assassins.

While some critics have argued that some of Sondheim’s musicals are less popular with the public because of their unusual lyrical sophistication and musical complexity, others have praised these features of his work, as well as the interplay of lyrics and music in his shows. Some of Sondheim's notable innovations include a show presented in reverse (Merrily We Roll Along) and the above-mentioned Anyone Can Whistle, in which Act 1 ends with the cast informing the audience that they are mad.

Jerry Herman played a significant role in American musical theatre, beginning with his first Broadway production, Milk and Honey (1961, 563 performances), about the founding of the state of Israel, and continuing with the smash hits Hello, Dolly! (1964, 2,844 performances), Mame (1966, 1,508 performances), and La Cage aux Folles (1983, 1,761 performances). Even his less successful shows like Dear World (1969) and Mack & Mabel (1974) have had memorable scores (Mack & Mabel was later reworked into a London hit). Writing both words and music, many of Herman's showtunes have become popular standards, including "Hello, Dolly!", "We Need a Little Christmas", "I Am What I Am", "Mame", "The Best of Times", "Before the Parade Passes By", "Put On Your Sunday Clothes", "It Only Takes a Moment", "Bosom Buddies", and "I Won't Send Roses", recorded by such artists as Louis Armstrong, Eydie Gorme, Barbra Streisand, Petula Clark and Bernadette Peters. Herman's songbook has been the subject of two popular musical revues, Jerry's Girls (Broadway, 1985), and Showtune (off-Broadway, 2003).

The musical started to diverge from the relatively narrow confines of the 1950s. Rock music would be used in several Broadway musicals, beginning with Hair, which featured not only rock music but also nudity and controversial opinions about the Vietnam War.

Social themes

After Show Boat and Porgy and Bess, and as the struggle in America and elsewhere for minorities' civil rights progressed, Hammerstein, Harold Arlen, Yip Harburg and others were emboldened to write more musicals and operas which aimed to normalize societal toleration of minorities and urged racial harmony. Early Golden Age works that focused on racial tolerance included Finian's Rainbow, South Pacific, and the The King and I. Towards the end of the Golden Age, several shows tackled Jewish subjects and issues, such as Fiddler on the Roof, Milk and Honey, Blitz! and later Rags. The original concept that became West Side Story was set in the Lower East Side during Easter-Passover celebrations; the rival gangs were to be Jewish and Italian Catholic. The creative team later decided that the Polish (white) vs. Puerto Rican conflict was fresher.[20]

Tolerance as an important theme in musicals has continued in recent decades. The final expression of West Side Story left a message of racial tolerance. By the end of the '60s, musicals became racially integrated, with black and white cast members even covering each others' roles, as they did in Hair. Casting in some musicals is an attempt to represent the community at the subject of the drama, as in Rent and In the Heights. Homosexuality has been explored in such musicals, beginning with Hair, and even more overtly in La Cage aux Folles and Falsettos. Parade is a sensitive exploration of both anti-Semitism and historical American racism.

More recent eras

1970s

After the success of Hair, rock musicals flourished in the 1970s, with Jesus Christ Superstar, Godspell, Grease and Two Gentlemen of Verona. Some of these rock musicals began with "concept albums" and then moved to film or stage, such as Tommy. Others had no dialogue or were otherwise reminiscent of opera, with dramatic, emotional themes; these sometimes started as concept albums and were referred to as rock operas. The musical also went in other directions. Shows like Raisin, Dreamgirls, Purlie, and The Wiz brought a significant African-American influence to Broadway. More varied musical genres and styles were incorporated into musicals both on and especially off-Broadway.

1975 brought one of the great contemporary musicals to the stage. A Chorus Line emerged from recorded group therapy-style sessions Michael Bennett conducted with Gypsies — those who sing and dance in support of the leading players —from the Broadway community. From hundreds of hours of tapes, James Kirkwood, Jr. and Nick Dante fashioned a book about an audition for a musical, incorporating into it many of the real-life stories of those who had sat in on the sessions — and some of whom eventually played variations of themselves or each other in the show. With music by Marvin Hamlisch and lyrics by Edward Kleban, A Chorus Line first opened at Joseph Papp's Public Theater in lower Manhattan. Advance word-of-mouth— that something extraordinary was about to explode — boosted box office sales, and after critics ran out of superlatives to describe what they witnessed on opening night, what initially had been planned as a limited engagement eventually moved to the Shubert Theatre uptown for a run that seemed to last forever. The show swept the Tony Awards and won the Pulitzer Prize, and its hit song, What I Did for Love, became an instant standard.

Clearly, Broadway audiences were eager to welcome musicals that strayed from the usual style and substance. John Kander and Fred Ebb explored pre-World War II Nazi Germany in Cabaret and Prohibition-era Chicago, which relied on old vaudeville techniques to tell its tale of murder and the media. Pippin, by Stephen Schwartz, was set in the days of Charlemagne. Federico Fellini's autobiographical film 8½ became Maury Yeston's Nine. At the end of the decade, Evita gave a more serious political biography than audiences were used to at musicals, and Sweeney Todd was the precursor to the darker, big budget musicals of the 1980s like Les Misérables, Miss Saigon, and The Phantom of the Opera, that depended on dramatic stories, sweeping scores and spectacular effects. But during this same period, old-fashioned values were still embraced in such hits as Annie, 42nd Street, My One and Only, and popular revivals of No, No, Nanette and Irene.

1980s and 1990s

The 1980s and 1990s saw the influence of European "mega-musicals" or "pop operas," which typically featured a pop-influenced score and had large casts and sets and were identified as much by their notable effects—a falling chandelier (in Phantom), a helicopter landing on stage (in Miss Saigon)—as they were by anything else in the production. Many were based on novels or other works of literature. The most important writers of mega-musicals include the French team of Claude-Michel Schönberg and Alain Boublil, responsible for Les Misérables, which became the longest-running international musical hit in history. The team, in collaboration with Richard Maltby, Jr., continued to produce hits with Miss Saigon (inspired by the Puccini opera Madame Butterfly). The British composer Andrew Lloyd Webber, saw similar mega-success with Evita, based on the life of Argentina's Eva Perón, and Cats, derived from the poems of T. S. Eliot, both of which musicals originally starred Elaine Paige, who with continued success has become known as the First Lady of British Musical Theatre. Other Lloyd Webber musical successes include Starlight Express, famous for being performed on rollerskates; The Phantom of the Opera, derived from the novel "Le Fantôme de l'Opéra" written by Gaston Leroux; and Sunset Boulevard (from the classic film of the same name). Several of these mega-musicals ran (or are still running) for decades in both New York and London. The 90s also saw the influence of large corporations on the production of musicals. The most important has been The Walt Disney Company, which began adapting some of its animated movie musicals—such as Beauty and the Beast and The Lion King—for the stage, and also created original stage productions like Aida, with music by Elton John. Disney continues to create new musicals for Broadway and West End theatres, such as, Tarzan, a stage adaptation of the classic Mary Poppins, and, most recently, a stage version of 1989's The Little Mermaid.

With the growing scale (and cost) of musicals, style was sometimes emphasized in favor of substance during the last two decades of the 20th century. At the same time, however, many writers broke from this pattern and began to create smaller scale, but critically-acclaimed and financially successful musicals, such as Falsettoland, Passion, Little Shop of Horrors, Bat Boy: The Musical, and Blood Brothers. The topics vary widely, and the music ranges from rock to pop, but they often are produced off-Broadway (or for smaller London theatres) and feature smaller casts and generally less expensive productions. Some of these have been noted as imaginative and innovative.[21]

The cost of tickets to Broadway and West End musicals was escalating beyond the budget of many theatregoers, and the trend was for these musicals to be viewed by a smaller and smaller audience. Jonathan Larson's musical Rent (based on the opera La Bohème) attempted to increase the popularity of musicals among a younger audience. It features a cast of twentysomethings, and the score is heavily rock-influenced. The musical became a hit, even with its composer dying of an aortic aneurysm on the night of the final dress rehearsal at New York Theatre Workshop, before he could see it reach Broadway. A group of young fans, styled RENTheads, line up at the Nederlander Theatre hours early in hopes of winning the lottery for $20 front row tickets, and some have seen the show more than 50 times. Other writers who have attempted to bring a taste of modern rock music to the stage include Jason Robert Brown.

Another trend has been to create a minimal plot to fit a collection of songs that have already been hits. These have included Buddy - The Buddy Holly Story (1995), Movin' Out (2002, based on the tunes of Billy Joel), Good Vibrations (the Beach Boys), All Shook Up (Elvis Presley), Jersey Boys (2006, The Four Seasons), Daddy Cool—The Boney M Musical, and many others. This style is often referred to as the "jukebox musical". Similar but more plot-driven musicals have been built around the canon of a particular pop group including Mamma Mia! (1999, featuring songs by ABBA), Our House (based on the songs of Madness), and We Will Rock You (based on the works of Queen).

2000s

- Recent trends

In recent years, familiarity has been embraced by producers anxious to guarantee that they recoup their considerable investments, if not show a healthy profit. Some are willing to take (usually modest-budget) chances on the new and unusual, such as Urinetown (2001), Bombay Dreams (2002; about the Bollywood musicals churned out by Indian cinema), Avenue Q (2003; utilizes puppets to tell its adult-themed story) and The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee (2005; people watching the show can become "spellers" in the show). But the majority prefer to hedge their bets by sticking with revivals of familiar fare like Wonderful Town or Fiddler on the Roof, or proven hits like La Cage aux Folles. Today's composers are finding their sources in already proven material, such as films (roughly one-third of current Broadway musicals, including The Producers, Spamalot, Hairspray, Legally Blonde, Billy Elliot, The Color Purple, and Grey Gardens) or literature (such as Little Women, The Scarlet Pimpernel, Dracula, and Wicked) hoping that the shows will have a built-in audience as a result. The reuse of plots, especially those from The Walt Disney Company, has been considered by some critics to be a redefinition of Broadway: rather than a creative outlet, it has become a tourist attraction.[7]

The musical is being pulled in a number of different directions. It is less likely today that a sole producer—a David Merrick or a Cameron Mackintosh—backs a production. Corporate sponsors dominate Broadway, and often alliances are formed to stage musicals which require an investment of $10 million or more. In 2002, the credits for Thoroughly Modern Millie listed ten producers, and among those names were entities comprised of several individuals. Typically, off-Broadway and regional theatres tend to produce smaller and therefore less expensive musicals, and development of new musicals has increasingly taken place outside of New York and London or in smaller venues. Spring Awakening was developed off-Broadway before being launched on Broadway in 2006.

It also appears that the spectacle format is on the rise again, returning to the times when Romans would have mock sea battles on stage. This was true of Starlight Express and is most apparent in the musical adaptation of The Lord of the Rings that ran in Toronto, Canada in 2006, and opened for previews in May 2007 at the Theatre Royal, Drury Lane in London, billed as the biggest stage production in musical theatre history. The expensive production lost money in Toronto. Conversely, The Drowsy Chaperone, The 25th Annual Putnam County Spelling Bee, Xanadu and others are part of a Broadway trend to present musicals uninterrupted by an intermission, with short running time of less than two hours. The latter two, together with works like Avenue Q, also represent a trend towards presenting smaller-scale, small cast musicals that are able to show a good profit in a smaller house.

- Renaissance of the movie-musical and TV "musicals"

After the 1996 film of Evita, the first successful movie musical in nearly two decades, Baz Luhrmann continued the revival of the movie musical with Moulin Rouge! (2001). This was followed by a number of film successes, including Chicago in 2002, Phantom of the Opera in 2004, Dreamgirls in 2006, and Hairspray and Sweeney Todd in 2007. Dr. Seuss's How the Grinch Stole Christmas! (2000) and The Cat in the Hat (2003), made the children's book into live-action musicals. Disney and other animated musicals and more adult animated musical films, like South Park: Bigger, Longer & Uncut (1999), paved the way for the revival of the movie musical. In addition, India is producing numerous "Bollywood" film musicals, and Japan is producing "Anime" film musicals. Occasionally, "made for TV" movies, such as Gypsy (1993), and Cinderella (1997), are made in musical format.

Some recent television shows have set an episode as a musical as a play on their usual format (examples include episodes of Ally McBeal, Buffy the Vampire Slayer's episode Once More, with Feeling, That's So Raven, Daria's episode Daria!, Oz's Variety, Space Ghost Coast to Coast's O Coast to Coast!/Boatshow, Scrubs (in an episode written by the creators of Avenue Q), and the 100th Episode of That '70s Show) or have included scenes where characters suddenly begin singing and dancing in a musical-theatre style during an episode, such as in several episodes of The Simpsons, 30 Rock, Hannah Montana, South Park, and Family Guy. The television series Cop Rock, extensively used the musical format as does the series The Mighty Boosh.

There have also been musicals made for the internet, including Dr. Horrible's Sing-Along Blog, about a low-rent supervillain played by Neil Patrick Harris. It was written during the WGA writer's strike.[22]

International musicals

The U.S. and Britain were the most active sources of book musicals from the 19th century through much of the 20th century (although Europe produced various forms of popular light opera and operetta, for example Spanish Zarzuela, during that period and even earlier). However, the light musical stage in other countries has become more active in recent decades.

Musicals from other English speaking countries (notably Australia and Canada) often do well locally, and occasionally even reach Broadway or the West End (e.g., The Boy from Oz and The Drowsy Chaperone). South Africa has an active musical theatre scene, with revues like African Footprint and Umoja and book musicals, such as Kat and the Kings and Taliep Petersen and Sarafina! touring internationally. Locally, musicals like Vere, Love and Green Onions, Over the Rainbow: the all-new all-gay... extravaganza and Bangbroek Mountain have been produced successfully.

Successful musicals from continental Europe include shows from (among other countries) Germany (Elixier and Ludwig II ), Austria (Dance of the Vampires and Elisabeth), Czech Republic (Angelika), France (Notre Dame de Paris, Les Misérables, Angélique, Marquise des Anges and Romeo & Juliette) and Spain (Hoy No Me Puedo Levantar).

Japan has recently seen the growth of an indigenous form of musical theatre, both animated and live action, mostly based on Anime and Manga, such as Kiki's Delivery Service and Tenimyu. The popular Sailor Moon metaseries has had twenty-nine Sailor Moon musicals, spanning thirteen years. Beginning in 1914, a series of popular revues have been performed by the all-female Takarazuka Revue, which currently fields five performing troupes. Elsewhere in Asia, the Indian Bollywood musical, mostly in the form of motion pictures, is tremendously successful. Hong Kong's first modern musical, produced in both Mandarin and Cantonese, is Snow.Wolf.Lake.

Other countries with an especially active musicals scene include the Netherlands, Italy, Sweden, Mexico, Brazil, Argentina, Russia, Turkey and China.

Relevance

The Broadway League (formerly "The League of American Theatres and Producers") announced that in the 2007-08 season, 12.27 million tickets were purchased for Broadway shows for a gross sale amount of almost a billion dollars.[23] The League further reported that during the 2006-07 season, approximately 65% of Broadway tickets were purchased by tourists, and that foreign tourists were 16% of attendees.[24] (This does not include off-Broadway and smaller venues.) The Society of London Theatre reported that 2007 set a record for attendance in London. Total attendees in the major commercial and grant-aided theatres in Central London were 13.6 million, and total ticket revenues were £469.7 million.[25] Also, as noted above, the international musicals scene has been particularly active in recent years.

However, Stephen Sondheim has been less than optimistic:

- "You have two kinds of shows on Broadway – revivals and the same kind of musicals over and over again, all spectacles. You get your tickets for The Lion King a year in advance, and essentially a family... pass on to their children the idea that that's what the theater is – a spectacular musical you see once a year, a stage version of a movie. It has nothing to do with theater at all. It has to do with seeing what is familiar.... I don't think the theatre will die per se, but it's never going to be what it was.... It's a tourist attraction."[26]

The success of original material like Avenue Q, Urinetown, and Spelling Bee, as well as creative re-imaginings of film properties, including Thoroughly Modern Millie, Hairspray, Billy Elliot and The Color Purple, and plays-turned-musicals, such as Spring Awakening prompts Broadway historian John Kenrick to write: "Is the Musical dead? ...Absolutely not! Changing? Always! The musical has been changing ever since Offenbach did his first rewrite in the 1850s. And change is the clearest sign that the musical is still a living, growing genre. Will we ever return to the so-called "golden age," with musicals at the center of popular culture? Probably not. Public taste has undergone fundamental changes, and the commercial arts can only flow where the paying public allows."[7]

Musical theatre in East Asian traditions

China

India

See also

- List of musicals

- List of musicals by composer

- Cast recording

- Show tunes

- Industrial musical

- List of musical theatre composers

- List of the 100 Longest-Running Broadway shows

- Long-running musical theatre productions

- List of Tony Award and Olivier Award winning musicals

- List of choreographers

- AFI's 100 Years of Musicals

- Euphemism

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Sheridan, Morley. Spread A Little Happiness, New York: Thames and Hudson, 1987, p.15

- ↑ The Cambridge Companion to the Musical, William A. Everett and Paul R. Laird eds., Chapter by Thomas L. Riis with Ann Sears and William A. Everett, Cambridge University Press, 2002, ISBN 0 521 79189 8, p. 137

- ↑ Sondheim website

- ↑ Brantley, Ben. "Curtain Up! It’s Patti’s Turn", New York Times, March 28, 2008

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Study guide history of musical theatre

- ↑ See Flynn, Denny Martin. Musical: A Grand Tour (New York: Schirmer Books, 1997), p. 22.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Article on the Musicals 101 website

- ↑ See Rochard H. Hoppin, Medieval Music (New York: W.W. Norton & Co, 1978), pp. 180-181.

- ↑ Article on long-running musicals before 1920

- ↑ Article on long-running musicals before 1920

- ↑ The Chimes of Normandy, 1878 (adapted from the French Les Cloches de Corneville), ran for 705 performances in London, beating any of the Gilbert and Sullivan pieces. Its run was not exceeded by any other piece of musical theatre until Dorothy broke its record in 1886

- ↑ Article on long-running musicals before 1920

- ↑ Midkoff, Neil article

- ↑ Irene 's run of 670 performances was a Broadway record that held until 1938's Hellzapoppin.

- ↑ Lamb, Andrew. "From Pinafore to Porter: United States-United Kingdom Interactions in Musical Theater, 1879–1929", American Music, Vol. 4, No. 1, British-American Musical Interactions (Spring, 1986), pp. 34-49, University of Illinois Press, retrieved September 18, 2008

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 "American Musical Theatre: An Introduction", theatrehistory.com, republished from The Complete Book of Light Opera. Mark Lubbock. New York: Appleton-Century-Crofts, 1962. pp. 753-56, accessed December 3, 2008

- ↑ Information about As Thousands Cheer

- ↑ Everett, William A. and Laird, Paul R. (2002), The Cambridge Companion to the Musical, Cambridge University Press, p. 124, ISBN 0521796393

- ↑ Suskin, Steven. "On the Record: Ernest In Love, Marco Polo, Puppets and Maury Yeston", Playbill.com, August 10, 2003.

- ↑ Arthur Laurents, Theatre: West Side Story; The Growth of an Idea, New York Herald Tribune, August 4, 1957. Reproduced on leonardbernstein.com. Accessed 12 February 2006.

- ↑ BroadwayBaby site article on Bat Boy

- ↑ Matt Roush (2008-06-30). "Exclusive: First Look at Joss Whedon's "Dr. Horrible"". Roush Dispatch. TV Guide. Retrieved on 2006-08-30.

- ↑ Announcement of 2007-08 Broadway Theatre Season Results, May 28, 2008

- ↑ "League Releases Annual "Demographics of the Broadway Audience Report" for 06-07", November 05, 2007

- ↑ Press Release "Record Attendances as Theatreland Celebrates 100 Years", Jan. 18, 2008

- ↑ quoted by Frank Rich in Conversations with Sondheim, New York Times Magazine, March 12, 2000, pp. 40 and 88

References

- Ganzl, Kurt. The Encyclopedia of Musical Theatre (3 Volumes). New York: Schirmer Books, 2001.

- The Broadway Musical Home

- The Cyber Encyclopedia of Musical Theatre, TV and Film

- Information from History.com

- Bloom, Ken; Frank Vlastnik (2004-10-01). Broadway Musicals : The 101 Greatest Shows of All Time. New York, New York: Black Dog & Leventhal Publishers. ISBN 1-57912-390-2.

- Kantor, Michael; Laurence Maslon (2004). Broadway: the American musical. New York, New York: Bulfinch Press. ISBN 0-8212-2905-2.

- Botto, Louis (2002-09-01). Robert Viagas. ed.. At This Theatre. Applause Books. ISBN 1-55783-566-7.

- Mordden, Ethan (1999). Beautiful Mornin': The Broadway Musical in the 1940s. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-512851-6.

- Article on history of musical theatre, focusing on American musicals

- Stacy's Musical Village - large musical theatre site

- Traubner, Richard. Operetta: A Theatrical History. Garden City, NY: Doubleday & Company, 1983

- Bauch, Marc. The American Musical. Marburg, Germany: Tectum Verlag, 2003. ISBN 382888458X described here

- Bauch, Marc. Themes and Topics of the American Musical after World War II. Marburg, Germany: Tectum Verlag, 2001. ISBN 3828811418 described here

External links

- A TIME collection of Broadway's evolution

- Australia's leading musical theatre website (aussietheatre.com)

- Internet Broadway Database (ibdb.com)

- Musical Cast Album Database (castalbumdb.com)

- Broadway.com - extensive theater site with news, photos and more

- Theatre.com - extensive theatre site with London news, photos and more

- Musical Cyberspace: Broadway and Beyond

- Science Fiction Musicals Sourcebook

- Musical Workshop - listings of contemporary musicals

- Edwardian theatre site with numerous midi files and other information

- Guide to Broadway

- List of articles available from British musical theatre publication The Gaiety and related publications

- Long running plays (over 400 performances) on Broadway, Off-Broadway, London, Toronto, Melbourne, Paris, Vienna, and Berlin

- Class Act Movie Musicals

- The Broadway Musical Home

- League of American Theatres amd Producers

- Broadway In Chicago

- Thoroughly modern 'movicals' Friday November 04 2005, Arts Hub

- A Tube Map of Musical Theatre HIstory

- A Guide to musical theatre detailing synopsis, cast lists, song lists and rights holder, etc

- MMD - development organisation for writers of new musicals