Mount St. Helens

| Mount St. Helens | |

|---|---|

3,000 ft (1 km) steam plume on May 19, 1982 |

|

| Elevation | 8,365 feet (2,550 m) |

| Location | Washington, USA |

| Range | Cascade Range |

| Prominence | 4,605 feet (1,404 m) |

| Topo map | USGS Mount St. Helens |

| Type | Active stratovolcano |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Age of rock | < 40,000 yrs |

| Last eruption | 2004–July 10, 2008 |

| First ascent | 1853 by Thomas J. Dryer |

| Easiest route | Hike via south slope of volcano (closest area near eruption site) |

Mount St. Helens is an active stratovolcano located in Skamania County, Washington, in the Pacific Northwest region of the United States. It is 96 miles (154 km) south of Seattle and 53 miles (85 km) northeast of Portland, Oregon. Mount St. Helens takes its English name from the British diplomat Lord St Helens, a friend of explorer George Vancouver who made a survey of the area in the late 18th century. The volcano is located in the Cascade Range and is part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc, a segment of the Pacific Ring of Fire that includes over 160 active volcanoes. This volcano is well known for its ash explosions and pyroclastic flows.

Mount St. Helens is most famous for its catastrophic eruption on May 18, 1980,[1] which was the deadliest and most economically destructive volcanic event in the history of the United States. Fifty-seven people were killed; 250 homes, 47 bridges, 15 miles (24 km) of railways, and 185 miles (298 km) of highway were destroyed. The eruption caused a massive debris avalanche, reducing the elevation of the mountain's summit from 9,677 feet (2,950 m) to 8,365 feet (2,550 m) and replacing it with a 1 mile (1.6 km) wide horseshoe-shaped crater.[2] The debris avalanche was up to 0.7 cubic miles (2.9 km3) in volume. The Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument was created to preserve the volcano and allow for its aftermath to be scientifically studied.

As with most other volcanoes in the Cascade Range, Mount St. Helens is a large eruptive cone consisting of lava rock interlayered with ash, pumice, and other deposits. The mountain includes layers of basalt and andesite through which several domes of dacite lava have erupted. The largest of the dacite domes formed the previous summit, and off its northern flank sat the smaller Goat Rocks dome. Both were destroyed in the 1980 eruption.

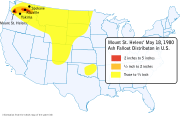

Shaken by an earthquake measuring 5.1 on the Richter scale, the north face of this tall symmetrical mountain collapsed in a massive rock debris avalanche. Nearly 230 square miles (600 km2) of forest was blown down or buried beneath volcanic deposits. At the same time a mushroom-shaped column of ash rose thousands of feet skyward and drifted downwind, turning day into night as dark, gray ash fell over eastern Washington and beyond. The eruption lasted 9 hours, but Mount St. Helens and the surrounding landscape were dramatically changed within moments.

Contents |

Geographic setting and description

General

Mount St. Helens is 45 miles (72 km) west of Mount Adams, in the western part of the Cascade Range. These "sister and brother" volcanic mountains are approximately 50 miles (80 km) from Mount Rainier, the highest of Cascade volcanoes. Mount Hood, the nearest major volcanic peak in Oregon, is 60 miles (97 km) southeast of Mount St. Helens.

Mount St. Helens is geologically young compared to the other major Cascade volcanoes. It formed only within the past 40,000 years, and the pre-1980 summit cone began rising about 2,200 years ago.[3] The volcano is considered the most active in the Cascades within the Holocene epoch (the last 10,000 or so years).[4]

Prior to the 1980 eruption, Mount St. Helens was the fifth-highest peak in Washington. It stood out prominently from surrounding hills because of the symmetry and extensive snow and ice cover of the pre-1980 summit cone, earning it the nickname "Fuji-san of America" ("Mount Fuji of America").[5] The peak rose more than 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above its base, where the lower flanks merge with adjacent ridges. The mountain is 6 miles (9.7 km) across at its base, which is at an altitude of 4,400 feet (1,300 m) on the northeastern side and 4,000 feet (1,200 m) elsewhere. At the pre-eruption tree line, the width of the cone was4 miles (6.4 km).

Streams that originate on the volcano enter three main river systems: the Toutle River on the north and northwest, the Kalama River on the west, and the Lewis River on the south and east. The streams are fed by abundant rain and snow. The average annual rainfall is 140 inches (3.6 m), and the snowpack on the mountain's upper slopes can reach 16 feet (4.9 m).[6] The Lewis River is impounded by three dams for hydroelectric power generation. The southern and eastern sides of the volcano drain into an upstream impoundment, the Swift Reservoir, which is directly south of the volcano's peak.

Although Mount St. Helens is in Skamania County, Washington, the best access routes to the mountain run through Cowlitz County to the west. State Route 504, locally known as the Spirit Lake Memorial Highway, connects with the heavily traveled Interstate 5 at Exit 49, 34 miles (55 km) to the west of the mountain. That major north-south highway skirts the low-lying cities of Castle Rock, Longview and Kelso along the Cowlitz River, and passes through the Vancouver, Washington-Portland, Oregon metropolitan area less than 50 miles (80 km) to the southwest. The community nearest the volcano is Cougar, Washington, in the Lewis River valley 11 miles (18 km) south-southwest of the peak. Gifford Pinchot National Forest surrounds Mount St. Helens.

Crater Glacier and other new rock glaciers

During the winter of 1980–1981, a new glacier appeared. Now officially named Crater Glacier, it was formerly known as the Tulutson Glacier. Shadowed by the crater walls and fed by heavy snowfall and repeated snow avalanches, it grew rapidly (14 feet (4.3 m) per year in thickness). By 2004, it covered about 0.36 square miles (0.93 km2), and was divided by the dome into a western and eastern lobe. Typically, by late summer, the glacier looks dark from rockfall from the crater walls and ash from eruptions. As of 2006, the ice had an average thickness of 328 feet (100 m) and a maximum of 656 feet (200 m), nearly as deep as the much older and larger Carbon Glacier of Mount Rainier. The ice is all post–1980, making the glacier very young geologically. However, the volume of the new glacier is about the same as all the pre–1980 glaciers combined.[7][8][9][10][11]

With the recent volcanic activity starting in 2004, the glacier lobes were pushed aside and upward by the growth of new volcanic domes. The surface of the glacier, once mostly uncrevassed, turned into a chaotic jumble of icefalls heavily criss-crossed with crevasses and seracs caused by movement of the crater floor.[12] The new domes have almost separated the Crater Glacier into an eastern and western lobe. Despite the volcanic activity, the termini of the glacier have still advanced, with a slight advance on the western lobe and a more considerable advance on the more shaded eastern lobe. Due to the advance, two lobes of the glacier joined together in late-May 2008 and thus the glacier completely surrounds the lava domes.[12][13][14] In addition, since 2004, new glaciers have formed on the crater wall above Crater Glacier feeding rock and ice onto its surface below; there are two rock glaciers to the north of the eastern lobe of Crater Glacier.[15]

Human history

Importance to Native Americans

Traces of ancient campsites have been found in the Gifford Pinchot National Forest, which surrounds the monument. Dating of these sites reveals that people have lived in this area for at least 6,500 years.[16] Throughout human history, Mount St. Helens eruptions have had a dramatic effect on the lives of local inhabitants. Work by archaeologists has shown that a massive eruption 3,500 years ago buried native settlements with a thick layer of pumice. As a result, people abandoned the area for nearly 2,000 years.[16] Later, members of the Cowlitz, Taidnapam, Klickitat, Upper Chinook, and Yakama tribes moved seasonally over the land, harvesting huckleberries and hunting salmon, elk, and deer.[16]

Local legends

American Indian lore contains numerous legends to explain the eruptions of Mount St. Helens and other Cascade volcanoes. The most famous of these is the Bridge of the Gods legend told by the Klickitats. In their tale, the chief of all the gods, Tyhee Saghalie and his two sons, Pahto (also called Klickitat) and Wy'east, traveled down the Columbia River from the Far North in search for a suitable area to settle.[17]

They came upon an area that is now called The Dalles and thought they had never seen a land so beautiful. The sons quarreled over the land, so to solve the dispute their father shot two arrows from his mighty bow — one to the north and the other to the south. Pahto followed the arrow to the north and settled there while Wy'east did the same for the arrow to the south. Saghalie then built Tanmahawis, the Bridge of the Gods, so his family could meet periodically.[17]

When the two sons of the Saghalie fell in love with a beautiful maiden named Loowit, she could not choose between them. The two young chiefs fought over her, burying villages and forests in the process. The area was devastated and the earth shook so violently that the huge bridge fell into the river, creating the cascades of the Columbia River Gorge.[18]

For punishment, Saghalie struck down each of the lovers and transformed them into great mountains where they fell. Wy'east, with his head lifted in pride, became the volcano known today as Mount Hood. Pahto, with his head bent toward his fallen love, was turned into Mount Adams. The fair Loowit became Mount St. Helens, known to the Klickitats as Louwala-Clough, which means "smoking or fire mountain" in their language (the Sahaptin called the mountain Loowit).[19]

Exploration by Europeans

Royal Navy Commander George Vancouver and the officers of HMS Discovery made the Europeans' first recorded sighting of Mount St. Helens on May 19, 1792, while surveying the northern Pacific Ocean coast. Vancouver named the mountain for British diplomat Alleyne Fitzherbert, 1st Baron St Helens on October 20, 1792,[19] as it came into view when the Discovery passed into the mouth of the Columbia River.

Years later, explorers, traders, and missionaries heard reports of an erupting volcano in the area. Geologists and historians determined much later that the eruption took place in 1800, marking the beginning of the 57-year-long Goat Rocks Eruptive Period (see geology section).[20] Alarmed by the "dry snow," the Nespelem tribe of northeastern Washington danced and prayed rather than collecting food and suffered during that winter from starvation.[20]

In late 1805 and early 1806, members of the Lewis and Clark Expedition spotted Mount St. Helens from the Columbia River but did not report either an ongoing eruption or recent evidence of one.[21] They did however report the presence of quicksand and clogged channel conditions at the mouth of the Sandy River near Portland, suggesting an eruption by Mount Hood sometime in the previous decades.

European settlement and use of the area

The area's first non-aboriginal inhabitants were European fur traders and trappers. Most of these men worked for the fur trading enterprise of the British-owned Hudson's Bay Company.[22] In the early 1890s, Ole' Peterson set up housekeeping at Cougar Flats, on the Upper Lewis River.[22] He was a true hermit — preferring to keep to himself, and enjoying the quiet solitude of nature.

Also in the early 1890s, a 156-square mile (404 km²) mining district north of Spirit Lake was established. By 1911, over 400 mining claims had been filed.[22] However, the minerals were never found in profitable quantities, and though much effort was spent in attempting to build a road or railroad into the district, by 1911, it was clear that there were no veins of precious minerals rich enough to offset the high transportation costs.[22]

The first authenticated eyewitness report of a volcanic eruption was made in March 1835 by Dr. Meredith Gairdner, while working for the Hudson's Bay Company stationed at Fort Vancouver.[23] He sent an account to the Edinburgh New Philosophical Journal, which published his letter in January 1836. James Dwight Dana of Yale University, while sailing with the United States Exploring Expedition, saw the quiescent peak from off the mouth of the Columbia River in 1841. Another member of the expedition later described "cellular basaltic lavas" at the mountain's base.[24]

In late fall or early winter of 1842, nearby settlers and missionaries witnessed the so-called "Great Eruption." This small-volume outburst created large ash clouds, and mild explosions followed for 15 years.[25] The eruptions of this period were likely phreatic (steam explosions). The Reverend Josiah Parrish in Champoeg, Oregon, witnessed Mount St. Helens in eruption on November 22, 1842. Ash from this eruption may have reached The Dalles, Oregon, 48 miles (80 km) southeast of the volcano.[4]

In October 1843, future California governor Peter H. Burnett recounted a story of an aboriginal American man who badly burned his foot and leg in lava or hot ash while hunting for deer. The likely apocryphal story went that the injured man sought treatment at Fort Vancouver, but the contemporary fort commissary steward, Napolean McGilvery, disclaimed knowledge of the incident.[26] British lieutenant Henry J. Warre sketched the eruption in 1845, and two years later Canadian painter Paul Kane created watercolors of the gently smoking mountain. Warre's work showed erupting material from a vent about a third of the way down from the summit on the mountain's west or northwest side (possibly at Goat Rocks), and one of Kane's field sketches shows smoke emanating from about the same location.[27]

On April 17, 1857, the Republican, a Steilacoom, Washington newspaper, reported that "Mount St. Helens, or some other mount to the southward, is seen ... to be in a state of eruption".[28] The lack of a significant ash layer associated with this event indicates that it was a small eruption. This was the first reported volcanic activity since 1854.[28]

Before the 1980 eruption, Spirit Lake offered year-round recreational activities. In the summer there was boating, swimming, and camping, while in the winter there was skiing.

Human impact from the 1980 eruption

St. Helens catastrophically erupted on May 18, 1980. After many months of lead-up activity, including the growth of a huge bulge on the north part of the mountain, a moderate earthquake caused the entire north flank of the mountain to slide away in the largest landslide in recorded history.[29] The newly-exposed hot and pressurized rock in the volcano responded by producing the largest historic volcanic eruption in the 48 contiguous U.S. states.[29] (See the Geology section for more detail.)

During the lead-up to the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens, 83-year-old Harry R. Truman, who had lived near the mountain for 54 years, became famous when he decided not to evacuate before the impending eruption, despite repeated pleas by local authorities. His body was never found after the eruption. Fifty-seven people were killed or never found. Had the eruption occurred one day later, when loggers would have been at work, rather than on a Sunday, the death toll would almost certainly have been much higher.[6]

Among the victims of the 1980 eruption was 30-year-old volcanologist David A. Johnston, who was stationed on the nearby Coldwater Ridge. Moments before his position was hit by the hot ash cloud, Johnston uttered his famous last words: "Vancouver! Vancouver! This is it!"[30] Johnston's body was never found.

U.S. President Jimmy Carter surveyed the damage and said "Someone said this area looked like a moonscape. But the moon looks more like a golf course compared to what's up there."[31] A film crew, led by Seattle filmmaker Otto Seiber, was dropped by helicopter on St. Helens on May 23 to document the destruction. Their compasses, however, spun in circles and they quickly became lost. A second eruption occurred on May 25, but the crew survived and was rescued two days later by National Guard helicopter pilots. Their film, The Eruption of Mount St. Helens, later became a popular documentary.

Protection and later history

In 1982, President Ronald Reagan and the U.S. Congress established the Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument, a 110,000 acres (450 km2) area around the mountain and within the Gifford Pinchot National Forest.[32]

Following the 1980 eruption, the area was left to gradually return to its natural state. In 1987, the National Forest Service reopened the mountain to climbing. It remained open until 2004 when renewed activity caused the closure of the area around the mountain (see Geology section for more detail).

Most notable was the closure of the Monitor Ridge trail, which previously let up to 100 permitted hikers per day climb to the summit. However, on July 21, 2006, the mountain was again opened to climbers.[33]

Geologic history

Ancestral stages of eruptive activity

The early eruptive stages of Mount St. Helens are known as the "Ape Canyon Stage" (around 40–35,000 years ago), the "Cougar Stage" (ca. 20–18,000 years ago), and the "Swift Creek Stage" (roughly 13–8,000 years ago).[34] The modern period, since about 2500 BCE, is called the "Spirit Lake Stage." Collectively, the pre-Spirit Lake stages are known as the "ancestral stages." The ancestral and modern stages differ primarily in the composition of the erupted lavas; ancestral lavas consisted of a characteristic mixture of dacite and andesite, while modern lava is very diverse (ranging from olivine basalt to andesite and dacite).[35]

St. Helens started its growth in the Pleistocene 37,600 years ago, during the Ape Canyon stage, with dacite and andesite eruptions of hot pumice and ash.[35] 36,000 years ago a large mudflow cascaded down the volcano;[35] mudflows were significant forces in all of St. Helens' eruptive cycles. The Ape Canyon eruptive period ended around 35,000 years ago and was followed by 17,000 years of relative quiet. Parts of this ancestral cone were fragmented and transported by glaciers 14,000 to 18,000 years ago during the last glacial period of the current ice age.[35]

The second eruptive period, the Cougar Stage, started 20,000 years ago and lasted for 2,000 years.[35] Pyroclastic flows of hot pumice and ash along with dome growth occurred during this period. Another 5,000 years of dormancy followed, only to be upset by the beginning of the Swift Creek eruptive period, typified by pyroclastic flows, dome growth and blanketing of the countryside with tephra. Swift Creek ended 8,000 years ago.

Smith Creek and Pine Creek eruptive periods

A dormancy of about 4,000 years was broken around 2500 BCE with the start of the Smith Creek eruptive period, when eruptions of large amounts of ash and yellowish-brown pumice covered thousands of square miles. An eruption in 1900 BCE was the largest known eruption from St. Helens during the Holocene epoch, judged by the volume of one of the tephra layers from that period. This eruptive period lasted until about 1600 BCE and left 18 inches (46 cm) deep deposits of material 50 miles (80 km) distant in what is now Mt. Rainier National Park. Trace deposits have been found as far northeast as Banff National Park in Alberta, and as far southeast as eastern Oregon.[36] All told there may have been up to 2.5 cubic miles (10 km3) of material ejected in this cycle.[36] Some 400 years of dormancy followed.

St. Helens came alive again around 1200 BCE — the Pine Creek eruptive period.[36] This lasted until about 800 BCE and was characterized by smaller-volume eruptions. Numerous dense, nearly red hot pyroclastic flows sped down St. Helens' flanks and came to rest in nearby valleys. A large mudflow partly filled 40 miles (64 km) of the Lewis River valley sometime between 1000 BCE and 500 BCE.

Castle Creek and Sugar Bowl eruptive periods

The next eruptive period, the Castle Creek period, began about 400 BCE, and is characterized by a change in composition of St. Helens' lava, with the addition of olivine and basalt.[37] The pre-1980 summit cone started to form during the Castle Creek period. Significant lava flows in addition to the previously much more common fragmented and pulverized lavas and rocks (tephra) distinguished this period. Large lava flows of andesite and basalt covered parts of the mountain, including one around the year 100 CE that traveled all the way into the Lewis and Kalama river valleys.[37] Others, such as Cave Basalt (known for its system of lava tubes), flowed up to 9 miles (14 km) from their vents.[37] During the first century, mudflows moved 30 miles (48 km) down the Toutle and Kalama river valleys and may have reached the Columbia River. Another 400 years of dormancy ensued.

The Sugar Bowl eruptive period was short and markedly different from other periods in Mount St. Helens history. It produced the only unequivocal laterally directed blast known from Mount St. Helens before the 1980 eruptions.[38] During Sugar Bowl time, the volcano first erupted quietly to produce a dome, then erupted violently at least twice producing a small volume of tephra, directed-blast deposits, pyroclastic flows, and lahars.[38]

Kalama and Goat Rocks eruptive periods

Roughly 700 years of dormancy were broken about 1480, when large amounts of pale gray dacite pumice and ash started to erupt, beginning the Kalama period. The eruption in 1480 was several times larger than the May 18, 1980 eruption.[38] In 1482, another large eruption rivaling the 1980 eruption in volume is known to have occurred.[38] Ash and pumice piled 6 miles (9.7 km) northeast of the volcano to a thickness of 3 feet (0.91 m); 50 miles (80 km) away, the ash was 2 inches (5.1 cm) deep. Large pyroclastic flows and mudflows subsequently rushed down St. Helens' west flanks and into the Kalama River drainage system.

This 150-year period next saw the eruption of less silica-rich lava in the form of andesitic ash that formed at least eight alternating light- and dark-colored layers.[37] Blocky andesite lava then flowed from St. Helens' summit crater down the volcano's southeast flank.[37] Later, pyroclastic flows raced down over the andesite lava and into the Kalama River valley. It ended with the emplacement of a dacite dome several hundred feet (~100 m) high at the volcano's summit, which filled and overtopped an explosion crater already at the summit.[20] Large parts of the dome's sides broke away and mantled parts of the volcano's cone with talus. Lateral explosions excavated a notch in the southeast crater wall. St. Helens reached its greatest height and achieved its highly symmetrical form by the time the Kalama eruptive cycle ended, about 1647.[20] 150 years of quiet returned to the volcano.

The 57-year eruptive period that started in 1800 was named after the Goat Rocks dome, and is the first time that both oral and written records exist.[20] Like the Kalama period, the Goat Rocks period started with an explosion of dacite tephra, followed by an andesite lava flow, and culminated with the emplacement of a dacite dome. The 1800 eruption probably rivalled the 1980 eruption in size, although it did not result in massive destruction of the cone. The ash drifted northeast over central and eastern Washington, northern Idaho, and western Montana. There were at least a dozen reported small eruptions of ash from 1831 to 1857, including a fairly large one in 1842. The vent was apparently at or near Goat Rocks on the northeast flank.[20] Goat Rocks dome was the site of the bulge in the 1980 eruption, and it was obliterated in the major eruption event on May 18, 1980 that destroyed the entire north face and top 1,300 feet (400 m) of the mountain.

Modern eruptive period

1980 to 2001 activity

On March 20, 1980, Mount St. Helens experienced a magnitude 4.2 earthquake.[1] Steam venting started on March 27.[39] By the end of April, the north side of the mountain started to bulge.[40] With little warning, a second earthquake of magnitude 5.1 May 18 triggered a massive collapse of the north face of the mountain. It was the largest known debris avalanche in recorded history. The magma inside of St. Helens burst forth into a large-scale pyroclastic flow that flattened vegetation and buildings over 230 square miles (600 km2). On the Volcanic Explosivity Index scale, the eruption was rated a five (a Plinian eruption).

The collapse of the northern flank of St. Helens mixed with ice, snow, and water to create lahars (volcanic mudflows). The lahars flowed many miles down the Toutle and Cowlitz Rivers, destroying bridges and lumber camps. A total of 3,900,000 cubic yards (2,980,000 m3) of material was transported 17 miles (27 km) south into the Columbia River by the mudflows.[41]

For more than nine hours, a vigorous plume of ash erupted, eventually reaching 12 to 16 miles (20 to 27 km) above sea level.[42] The plume moved eastward at an average speed of 60 miles per hour (95 km/h), with ash reaching Idaho by noon.

By about 5:30 p.m. on May 18, the vertical ash column declined in stature, and less severe outbursts continued through the night and for the next several days. The St. Helens May 18 eruption released 24 megatons of thermal energy;[43][44] it ejected more than 0.67 cubic miles (2.8 cubic km) of material.[29] The removal of the north side of the mountain reduced St. Helens' height by about 1,300 feet (400 m) and left a crater one to 2 miles (3.2 km) wide and 0.5 miles (800 m) deep, with its north end open in a huge breach. The eruption killed 57 people, nearly 7,000 big game animals (deer, elk, and bear), and an estimated 12 million fish from a hatchery.[6] It destroyed or extensively damaged over 200 homes, 185 miles (298 km) of highway and 15 miles (24 km) of railways.[6]

Between 1980 and 1986, activity continued at Mount St. Helens, with a new lava dome forming in the crater. Numerous small explosions and dome-building eruptions occurred. From December 7, 1989 to January 6, 1990, and from November 5, 1990 to February 14, 1991, the mountain erupted with sometimes huge clouds of ash.[45]

2004 to 2008 activity

Magma reached the surface of the volcano about October 11, 2004, resulting in the building of a new lava dome on the existing dome's south side. This new dome continued to grow throughout 2005 and into 2006. Several transient features were observed, such as the "whaleback," which comprised long shafts of solidified magma being extruded by the pressure of magma beneath. These features are fragile and break down soon after they are formed. On July 2, 2005, the tip of the whaleback broke off, causing a rockfall that sent ash and dust several hundred meters into the air. [46]

Mount St. Helens showed significant activity on March 8, 2005, when a 36,000 feet (11,000 m) plume of steam and ash emerged — visible from Seattle.[47] This relatively minor eruption was a release of pressure consistent with ongoing dome building. The release was accompanied by a magnitude 2.5 earthquake.

Another feature to emerge from the dome is called the "fin" or "slab." Approximately half the size of a football field, the large, cooled volcanic rock was being forced upward as quickly as 6 feet (2 m) per day.[48][49] In mid-June 2006, the slab was crumbling in frequent rockfalls, although it was still being extruded. The height of the dome was 7,550 feet (2,300 m), still below the height reached in July 2005 when the whaleback collapsed.

On October 22, 2006, at 3:13 p.m. PST, a magnitude 3.5 earthquake broke loose Spine 7. The collapse and avalanche of the lava dome sent an ash plume 2,000 feet (610 m) over the western rim of the crater; the ash plume then rapidly dissipated.

On December 19, 2006, a large white plume of condensing steam was observed, leading some media people to assume there had been a small eruption. However, the Cascades Volcano Observatory of the USGS does not mention any significant ash plume.[50] The volcano has been in continuous eruption since October 2004, but this eruption has in large part consisted of a gradual extrusion of lava forming a dome in the crater.

On January 16, 2008, steam began seeping from a fracture atop the lava dome. Associated seismic activity is the most noteworthy since 2004. Scientists have suspended activities in the crater and the mountain flanks, but the risk of a major eruption is deemed low.[51] During the end of January, the eruption paused; no more lava was being extruded from the lava dome. On July 10, 2008 it was determined that the eruption had ended after more than six months of no volcanic activity.[52]

See also

- Geology of the Pacific Northwest

- Cascade Volcanoes

- Silver Lake (Washington)

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument". USDA Forest Service. (accessed November 26, 2006)

- ↑ "May 18, 1980 Eruption of Mount St. Helens". USDA Forest Service. Retrieved on 2007-08-11.

- ↑ Mullineaux, The Eruptive History of Mount St. Helens, USGS Professional Paper 1250, page 3

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 USGS Description of Mount St. Helens, USGS.gov (accessed 15 Nov 2006)

- ↑ Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 201

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 Tilling et al., Eruptions of Mount St. Helens: Past, Present, and Future, USGS Special Interest Publication, 1990 (accessed 12 Nov 2006)

- ↑ Brugman, Melinda M.; Austin Post (1981). "USGS Circular 850-D: Effects of Volcanism on the Glaciers of Mount St. Helens". Retrieved on 2007-03-07.

- ↑ Wiggins, Tracy B.; Hansen, Jon D.; Clark, Douglas H. (2002). "Growth and flow of a new glacier in Mt. St. Helens Crater". Abstracts with Programs - Geological Society of America 34 (5): 91.

- ↑ Schilling, Steve P.; Paul E. Carrara, Ren A. Thompson, and Eugene Y. Iwatsubo (2004). "Posteruption glacier development within the crater of Mount St. Helens, Washington, USA". Quaternary Research (Elsevier Science (USA)) 61 (3): 325–329. doi:.

- ↑ McCandless, Melanie; Plummer, Mitchell; Clark, Douglas (2005). "Predictions of the growth and steady-state form of the Mount St. Helens Crater Glacier using a 2-D glacier model". Abstracts with Programs - Geological Society of America 37 (7): 354.

- ↑ Schilling, Steve P.; David W. Ramsey, James A. Messerich, and Ren A. Thompson (2006-08-08). "USGS Scientific Investigations Map 2928: Rebuilding Mount St. Helens". Retrieved on 2007-03-07.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Volcano Review" (PDF). US Forest Service. Retrieved on 2008-06-07.

- ↑ Schilling, Steve (2008-05-30). "MSH08_aerial_new_dome_from_north_05-30-08". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved on 2008-06-07. - Glacier is still connected south of the lava dome.

- ↑ Schilling, Steve (2008-05-30). "MSH08_aerial_st_helens_crater_from_north_05-30-08". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved on 2008-06-07. - Glacier arms touch on North end of glacier.

- ↑ Haugerud, R. A.; Harding, D. J., Mark, L. E.; Zeigler, J., Queija, V., Johnson, S. Y. (2004-12). "Lidar measurement of topographic change during the 2004 eruption of Mount St. Helens, WA". Retrieved on 2007-09-26.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 Native Americans, USGS (accessed 12 Nov 2006)

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 Archie Satterfield, Country Roads of Washington (Backinprint.com: 2003) ISBN 0-595-26863-3, page 82

- ↑ The Bridge of the Gods, theoutlaws.com (accessed November 26, 2006)

- ↑ 19.0 19.1 USGS. "Volcanoes and History: Cascade Range Volcano Names". Retrieved on 2006-10-20.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 20.2 20.3 20.4 20.5 Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 217

- ↑ Pringle, Roadside Geology of Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument and Vicinity

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Explorers and Settlers, USGS.gov (accessed 12 Nov 2006)

- ↑ Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 219

- ↑ The Volcanoes of Lewis and Clark, USGS.gov (accessed 15 Nov 2006)

- ↑ Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, pages 220–221

- ↑ Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 224

- ↑ Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 225, 227

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 228

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 29.2 Mount St. Helens – From the 1980 Eruption to 2000, USGS Fact Sheet 036-00 (accessed 12 Nov 2006)

- ↑ Scott LaFee. "Perish the thought: A life in science sometimes becomes a death, too." SignOnSanDiego.com: December 3, 2003. Retrieved October 26, 2006.

- ↑ Mount St. Helens: Senator Murray Speaks on the 25th Anniversary of the May 18, 1980 Eruption, Senate.gov (accessed 12 Nov 2006)

- ↑ Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument: General Visitor Information, USDA Forest Service (accessed 12 Nov 2006)

- ↑ Climbing Mount St. Helens, USDA Forest Service (accessed 12 Nov 2006)

- ↑ "Mount St. Helens - Summary of Volcanic History". USDA Forest Service. (accessed November 26, 2006)

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 35.2 35.3 35.4 Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 214

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 36.2 Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 215

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 37.2 37.3 37.4 Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 216

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 38.2 38.3 Mount St. Helens Eruptive History, USGS.gov (accessed 15 Nov 2006)

- ↑ "Summary of Events Leading Up to the May 18, 1980 Eruption of Mount St. Helens: March 22–28.". USDA Forest Service. Retrieved on 2006-10-28.

- ↑ "Summary of Events Leading Up to the May 18, 1980 Eruption of Mount St. Helens: April 26–May 2.". USDA Forest Service. Retrieved on 2006-10-28.

- ↑ Harris, Fire Mountains of the West, 1st edition, page 209

- ↑ Kiver and Harris, Geology of U.S. Parklands, 6th edition, page 149

- ↑ Mount St. Helens – From the 1980 Eruption to 2000, Fact Sheet 036-00 usgs.gov

- ↑ Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument fs.fed.us, '24 megatons thermal energy'

- ↑ Bobbie Myers, 1992, Small Explosions Interrupt 3-year Quiescence at Mount St. Helens, Washington: IN: Earthquakes and Volcanoes, v.23, n.2, p.58–73 (accessed November 26, 2006)

- ↑ see USGS before and after images

- ↑ Mount St. Helens, Washington, "Plume in the Evening", March 8, 2005, USGS.gov (accessed 15 Nov 2006)

- ↑ Northwest NewsChannel8. "New slab growing in Mount St. Helens dome". Retrieved on 2006-10-20.

- ↑ See close-up of the slab.

- ↑ Cascades Volcano Observatory, vulcan.wr.usgs.gov (accessed January 4, 2007)

- ↑ Small Quake Report- ap.google.com (accessed January 16, 2008)

- ↑ "CVO Menu - Mount St. Helens Eruption 2004". Vulcan.wr.usgs.gov. Retrieved on 2008-10-06.

References

- Harris, Stephen L. (1988). "Mount St. Helens: A Living Fire Mountain". Fire Mountains of the West: The Cascade and Mono Lake Volcanoes (1st edition ed.). Missoula, Montana: Mountain Press Publishing Company. pp. 201–228. ISBN 0-87842-220-X.

- Mullineaux, D.R.; Crandell, D.R. (1981). The Eruptive History of Mount St. Helens, USGS Professional Paper 1250. Retrieved on October 28, 2006.

- Mullineaux, D.R. (1996). Pre-1980 Tephra-Fall Deposits Erupted From Mount St. Helens, USGS Professional Paper 1563. Retrieved on October 28, 2006.

- Pringle (1993). Roadside Geology of Mount St. Helens National Volcanic Monument and Vicinity, Washington State Department of Natural Resources, Division of Geology and Earth Resources Information; Circular 88.

- USGS/Cascades Volcano Observatory, Vancouver, Washington. DESCRIPTION: Mount St. Helens Volcano, Washington. Retrieved on October 28, 2006.

External links

- Smithsonian Institution Global Volcanism Program: Mount St. Helens

- Mount St. Helens Watch links to webcams, live video feeds and news sites to monitor Mount St. Helens

- Mount St. Helens photographs and current conditions from the United States Geological Survey website

- The VolcanoCam image of Mount St. Helens automatically updated approximately every five minutes from the U.S. Forest Service. It is located at Johnston Ridge and is able to view the new dome, even at night when the glow of new magma may be visible via the camera's infrared capabilities.

- USGS: Mount St. Helens Eruptive History

- USGS: Mount St. Helens — From the 1980 Eruption to 2000

- Most recent photos (most aerial) from the United States Geological Survey

- Enhanced night time images of Mount St Helens

- Virtual Tour of Mt St Helens. Comparison of 2003 and 2006 crater

- University of Washington Libraries: Digital Collections:

- Mount St. Helens Post-Eruption Chemistry Database This collection contains photographs of Mount St. Helens, post-eruption, taken over the span of three years to provide a look at both the human and the scientific sides of studying the eruption of a volcano.

- Mount St. Helens Succession Collection This collection consists of 235 photographs in a study of plant habitats following the May 18, 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens.

- Audio recording of the May 18, 1980 eruption Recorded 140 miles (225 km) southwest of the mountain. Believed to be the only audio recording of the eruption.

|

||||||||||||||||