Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

| Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi | |

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi, pictured in the 1930's

|

|

| Born | 2 October 1869 Porbandar, Kathiawar Agency, British India |

|---|---|

| Died | 30 January 1948 (aged 78) New Delhi, Union of India |

| Cause of death | Assassination |

| Nationality | Indian |

| Other names | Mahatma Gandhi |

| Education | University College London |

| Known for | Indian Independence Movement |

| Political party | Indian National Congress |

| Religious beliefs | Hinduism |

| Spouse(s) | Kasturba Gandhi |

| Children | Harilal Manilal Ramdas Devdas |

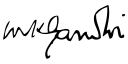

Signature

|

|

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi listen (Gujarati: મોહનદાસ કરમચંદ ગાંધી, IPA: [moɦən̪d̪äs kəɾəmʧən̪d̪ gän̪d̪ʱi]) (2 October 1869 – 30 January 1948) was a major political and spiritual leader of India and the Indian independence movement. He was the pioneer of Satyagraha—resistance to tyranny through mass civil disobedience, firmly founded upon ahimsa or total non-violence—which led India to independence and inspired movements for civil rights and freedom across the world. He is commonly known around the world as Mahatma Gandhi (Sanskrit: महात्मा mahātmā or "Great Soul", an honorific first applied to him by Rabindranath Tagore) and in India also as Bapu (Gujarati: બાપુ bāpu or "Father"). He is officially honoured in India as the Father of the Nation; his birthday, 2 October, is commemorated there as Gandhi Jayanti, a national holiday, and worldwide as the International Day of Non-Violence.

Gandhi first employed non-violent civil disobedience as an expatriate lawyer in South Africa, in the resident Indian community's struggle for civil rights. After his return to India in 1915, he set about organising peasants, farmers, and urban labourers in protesting excessive land-tax and discrimination. Assuming leadership of the Indian National Congress in 1921, Gandhi led nationwide campaigns for easing poverty, for expanding women's rights, for building religious and ethnic amity, for ending untouchability, for increasing economic self-reliance, but above all for achieving Swaraj—the independence of India from foreign domination. Gandhi famously led Indians in protesting the British-imposed salt tax with the 400 km (249 mi) Dandi Salt March in 1930, and later in calling for the British to Quit India in 1942. He was imprisoned for many years, on numerous occasions, in both South Africa and India.

Gandhi was a practitioner of non-violence and truth, and advocated that others do the same. He lived modestly in a self-sufficient residential community and wore the traditional Indian dhoti and shawl, woven with yarn he had hand spun on a charkha. He ate simple vegetarian food, and also undertook long fasts as means of both self-purification and social protest.

Early life

Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi[1] was born in Porbander, a coastal town in present-day Gujarat, Western India, on 2 October 1869. His father, Karamchand Gandhi, who belonged to the Hindu Modh community, was the diwan (Prime Minister) of the eponymous Porbander state, a small princely state in the Kathiawar Agency of British India. His mother, Putlibai, who came from the Hindu Pranami Vaishnava community, was Karamchand's fourth wife, the first three wives having apparently died in childbirth. Growing up with a devout mother and the Jain traditions of the region, the young Mohandas absorbed early the influences that would play an important role in his adult life; these included compassion to sentient beings, vegetarianism, fasting for self-purification, and mutual tolerance between individuals of different creeds.

In May 1883, the 13-year old Mohandas was married to 14-year old Kasturbai Makhanji (her first name was usually shortened to "Kasturba," and affectionately to "Ba") in an arranged child marriage, as was the custom in the region.[2] However, as was also the custom of the region, the adolescent bride was to spend much time at her parents' house, and away from her husband.[3] In 1885, when Gandhi was 15, the couple's first child was born, but survived only a few days; earlier that year, Gandhi's father, Karamchand Gandhi, had passed away.[4] Mohandas and Kasturbai had four more children, all sons: Harilal, born in 1888; Manilal, born in 1892; Ramdas, born in 1897; and Devdas, born in 1900. At his middle school in Porbandar and high school in Rajkot, Gandhi remained an average student academically. He passed the matriculation exam for Samaldas College at Bhavnagar, Gujarat with some difficulty. While there, he was unhappy, in part because his family wanted him to become a barrister.

On 4 September 1888, less than a month shy of his nineteenth birthday, Gandhi traveled to London, England, to study law at University College London and to train as a barrister. His time in London, the Imperial capital, was influenced by a vow he had made to his mother in the presence of the Jain monk Becharji, upon leaving India, to observe the Hindu precepts of abstinence from meat, alcohol, and promiscuity. Although Gandhi experimented with adopting "English" customs—taking dancing lessons for example—he could not stomach his landlady's mutton and cabbage. She pointed him towards one of London's few vegetarian restaurants. Rather than simply go along with his mother's wishes, he read about, and intellectually embraced vegetarianism. He joined the Vegetarian Society, was elected to its executive committee, and founded a local chapter. He later credited this with giving him valuable experience in organizing institutions. Some of the vegetarians he met were members of the Theosophical Society, which had been founded in 1875 to further universal brotherhood, and which was devoted to the study of Buddhist and Hindu literature. They encouraged Gandhi to read the Bhagavad Gita. Not having shown a particular interest in religion before, he read works of and about Hinduism, Christianity, Buddhism, Islam and other religions. He returned to India after being called to the bar of England and Wales by Inner Temple, but had limited success establishing a law practice in Mumbai. Later, after applying and being turned down for a part-time job as a high school teacher, he ended up returning to Rajkot to make a modest living drafting petitions for litigants, but was forced to close down that business as well when he ran afoul of a British officer. In his autobiography, he describes this incident as a kind of unsuccessful lobbying attempt on behalf of his older brother. It was in this climate that (in 1893) he accepted a year-long contract from an Indian firm to a post in Natal, South Africa, then part of the British Empire.

Civil rights movement in South Africa (1893–1914)

In South Africa, Gandhi faced discrimination directed at Indians. Initially, he was thrown off a train at Pietermaritzburg, after refusing to move from the first class to a third class coach while holding a valid first class ticket. Traveling further on by stagecoach, he was beaten by a driver for refusing to travel on the foot board to make room for a European passenger. He suffered other hardships on the journey as well, including being barred from many hotels. In another of many similar events, the magistrate of a Durban court ordered him to remove his turban, which Gandhi refused. These incidents have been acknowledged as a turning point in his life, serving as an awakening to contemporary social injustice and helping to explain his subsequent social activism. It was through witnessing firsthand the racism, prejudice and injustice against Indians in South Africa that Gandhi started to question his people's status within the British Empire, and his own place in society.

Gandhi extended his original period of stay in South Africa to assist Indians in opposing a bill to deny them the right to vote. Though unable to halt the bill's passage, his campaign was successful in drawing attention to the grievances of Indians in South Africa. He founded the Natal Indian Congress in 1894, and through this organization, he molded the Indian community of South Africa into a homogeneous political force. In January 1897, when Gandhi returned from a brief trip to India, a white mob attacked and tried to lynch him. In an early indication of the personal values that would shape his later campaigns, he refused to press charges against any member of the mob, stating it was one of his principles not to seek redress for a personal wrong in a court of law.

In 1906, the Transvaal government promulgated a new Act compelling registration of the colony's Indian population. At a mass protest meeting held in Johannesburg on 11 September that year, Gandhi adopted his still evolving methodology of satyagraha (devotion to the truth), or non-violent protest, for the first time, calling on his fellow Indians to defy the new law and suffer the punishments for doing so, rather than resist through violent means. This plan was adopted, leading to a seven-year struggle in which thousands of Indians were jailed (including Gandhi), flogged, or even shot, for striking, refusing to register, burning their registration cards, or engaging in other forms of non-violent resistance. While the government was successful in repressing the Indian protesters, the public outcry stemming from the harsh methods employed by the South African government in the face of peaceful Indian protesters finally forced South African General Jan Christiaan Smuts to negotiate a compromise with Gandhi. Gandhi's ideas took shape and the concept of Satyagraha matured during this struggle.

Role in Zulu War of 1906

In 1906, after the British introduced a new poll-tax, Zulus in South Africa killed two British officers. The British declared a war against the Zulus, in retaliation. Gandhi actively encouraged the British to recruit Indians. He argued that Indians should support the war efforts in order to legitimize their claims to full citizenship. The British, however, refused to offer Indians positions of rank in their military. However, they accepted Gandhi's offer to let a detachment of Indians volunteer as a stretcher bearer corps to treat wounded British soldiers. This corps was commanded by Gandhi. On 21 July 1906, Gandhi wrote in Indian Opinion: "The corps had been formed at the instance of the Natal Government by way of experiment, in connection with the operations against the Natives consists of twenty three Indians".[5] Gandhi urged the Indian population in South Africa to join the war through his columns in Indian Opinion: “If the Government only realized what reserve force is being wasted, they would make use of it and give Indians the opportunity of a thorough training for actual warfare.”[6]

In Gandhi's opinion, the Draft Ordinance of 1906 brought the status of Indians below the level of Natives. He therefore urged Indians to resist the Ordinance along the lines of Satyagraha, by taking the example of "Kaffirs". In his words, "Even the half-castes and kaffirs, who are less advanced than we, have resisted the government. The pass law applies to them as well, but they do not take out passes."[7]

In 1927 Gandhi wrote of the event: "The Boer War had not brought home to me the horrors of war with anything like the vividness that the [Zulu] 'rebellion' did. This was no war but a man-hunt, not only in my opinion, but also in that of many Englishmen with whom I had occasion to talk."[8]

Struggle for Indian Independence (1916–1945)

- See also: Indian Independence Movement

In 1915, Gandhi returned from South Africa to live in India. He spoke at the conventions of the Indian National Congress, but was primarily introduced to Indian issues, politics and the Indian people by Gopal Krishna Gokhale, a respected leader of the Congress Party at the time.

Champaran and Kheda

Gandhi's first major achievements came in 1918 with the Champaran agitation and Kheda Satyagraha, although in the latter it was indigo and other cash crops instead of the food crops necessary for their survival. Suppressed by the militias of the landlords (mostly British), they were given measly compensation, leaving them mired in extreme poverty. The villages were kept extremely dirty and unhygienic; and alcoholism, untouchability and purdah were rampant. Now in the throes of a devastating famine, the British levied an oppressive tax which they insisted on increasing. The situation was desperate. In Kheda in Gujarat, the problem was the same. Gandhi established an ashram there, organizing scores of his veteran supporters and fresh volunteers from the region. He organized a detailed study and survey of the villages, accounting for the atrocities and terrible episodes of suffering, including the general state of degenerate living. Building on the confidence of villagers, he began leading the clean-up of villages, building of schools and hospitals and encouraging the village leadership to undo and condemn many social evils, as accounted above.

But his main impact came when he was arrested by police on the charge of creating unrest and was ordered to leave the province. Hundreds of thousands of people protested and rallied outside the jail, police stations and courts demanding his release, which the court reluctantly granted. Gandhi led organized protests and strikes against the landlords, who with the guidance of the British government, signed an agreement granting the poor farmers of the region more compensation and control over farming, and cancellation of revenue hikes and its collection until the famine ended. It was during this agitation, that Gandhi was addressed by the people as Bapu (Father) and Mahatma (Great Soul). In Kheda, Sardar Patel represented the farmers in negotiations with the British, who suspended revenue collection and released all the prisoners. As a result, Gandhi's fame spread all over the nation.

Non-cooperation

Gandhi employed non-cooperation, non-violence and peaceful resistance as his "weapons" in the struggle against British. In Punjab, the Jallianwala Bagh massacre of civilians by British troops (also known as the Amritsar Massacre) caused deep trauma to the nation, leading to increased public anger and acts of violence. Gandhi criticized both the actions of the British Raj and the retaliatory violence of Indians. He authored the resolution offering condolences to British civilian victims and condemning the riots, which after initial opposition in the party, was accepted following Gandhi's emotional speech advocating his principle that all violence was evil and could not be justified.[9] But it was after the massacre and subsequent violence that Gandhi's mind focused upon obtaining complete self-government and control of all Indian government institutions, maturing soon into Swaraj or complete individual, spiritual, political independence.

In December 1921, Gandhi was invested with executive authority on behalf of the Indian National Congress. Under his leadership, the Congress was reorganized with a new constitution, with the goal of Swaraj. Membership in the party was opened to anyone prepared to pay a token fee. A hierarchy of committees was set up to improve discipline, transforming the party from an elite organization to one of mass national appeal. Gandhi expanded his non-violence platform to include the swadeshi policy — the boycott of foreign-made goods, especially British goods. Linked to this was his advocacy that khadi (homespun cloth) be worn by all Indians instead of British-made textiles. Gandhi exhorted Indian men and women, rich or poor, to spend time each day spinning khadi in support of the independence movement.[10] This was a strategy to inculcate discipline and dedication to weed out the unwilling and ambitious, and to include women in the movement at a time when many thought that such activities were not respectable activities for women. In addition to boycotting British products, Gandhi urged the people to boycott British educational institutions and law courts, to resign from government employment, and to forsake British titles and honours.

"Non-cooperation" enjoyed wide-spread appeal and success, increasing excitement and participation from all strata of Indian society. Yet, just as the movement reached its apex, it ended abruptly as a result of a violent clash in the town of Chauri Chaura, Uttar Pradesh, in February 1922. Fearing that the movement was about to take a turn towards violence, and convinced that this would be the undoing of all his work, Gandhi called off the campaign of mass civil disobedience.[11] Gandhi was arrested on 10 March 1922, tried for sedition, and sentenced to six years imprisonment. He began his sentence on 18 March 1922. He was released in February 1924 for an appendicitis operation, having served only 2 years.

Without Gandhi's uniting personality, the Indian National Congress began to splinter during his years in prison, splitting into two factions, one led by Chitta Ranjan Das and Motilal Nehru favouring party participation in the legislatures, and the other led by Chakravarti Rajagopalachari and Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, opposing this move. Furthermore, cooperation among Hindus and Muslims, which had been strong at the height of the non-violence campaign, was breaking down. Gandhi attempted to bridge these differences through many means, including a three-week fast in the autumn of 1924, but with limited success.[12]

Swaraj and the Salt Satyagraha (Salt March)

Gandhi stayed out of active politics and as such limelight for most of the 1920s, preferring to resolve the wedge between the Swaraj Party and the Indian National Congress, and expanding initiatives against untouchability, alcoholism, ignorance and poverty. He returned to the fore in 1928. The year before, the British government had appointed a new constitutional reform commission under Sir John Simon, which did not include any Indian as its member. The result was a boycott of the commission by Indian political parties. Gandhi pushed through a resolution at the Calcutta Congress in December 1928 calling on the British government to grant India dominion status or face a new campaign of non-cooperation with complete independence for the country as its goal. Gandhi had not only moderated the views of younger men like Subhas Chandra Bose and Jawaharlal Nehru, who sought a demand for immediate independence, but also reduced his own call to a one year wait, instead of two.[13] The British did not respond. On 31 December 1929, the flag of India was unfurled in Lahore. 26 January 1930 was celebrated by the Indian National Congress, meeting in Lahore, as India's Independence Day. This day was commemorated by almost every other Indian organization. Gandhi then launched a new satyagraha against the tax on salt in March 1930, highlighted by the famous Salt March to Dandi from 12 March to 6 April, marching 400 kilometres (248 miles) from Ahmedabad to Dandi, Gujarat to make salt himself. Thousands of Indians joined him on this march to the sea. This campaign was one of his most successful at upsetting British hold on India; Britain responded by imprisoning over 60,000 people. The government, represented by Lord Edward Irwin, decided to negotiate with Gandhi. The Gandhi–Irwin Pact was signed in March 1931. The British Government agreed to set all political prisoners free in return for the suspension of the civil disobedience movement. As a result of the pact, Gandhi was also invited to attend the Round Table Conference in London as the sole representative of the Indian National Congress. The conference was a disappointment to Gandhi and the nationalists, as it focused on the Indian princes and Indian minorities rather than the transfer of power. Furthermore, Lord Irwin's successor, Lord Willingdon, embarked on a new campaign of controlling and subduing the movement of the nationalists. Gandhi was again arrested, and the government attempted to negate his influence by completely isolating him from his followers. However, this tactic was not successful. In 1932, through the campaigning of the Dalit leader B. R. Ambedkar, the government granted untouchables separate electorates under the new constitution. In protest, Gandhi embarked on a six-day fast in September 1932, successfully forcing the government to adopt a more equitable arrangement via negotiations mediated by the Dalit cricketer turned political leader Palwankar Baloo. This was the start of a new campaign by Gandhi to improve the lives of the untouchables, whom he named Harijans, the children of God. On 8 May 1933 Gandhi began a 21-day fast of self-purification to help the Harijan movement.[14] This new campaign was not universally embraced within the Dalit community, however, as prominent leader B. R. Ambedkar condemned Gandhi's use of the term Harijans as saying that Dalits were socially immature, and that privileged caste Indians played a paternalistic role. Ambedkar and his allies also felt Gandhi was undermining Dalit political rights. Gandhi, although born into the Vaishya caste, insisted that he was able to speak on behalf of Dalits, despite the availability of Dalit activists such as Ambedkar.

In the summer of 1934, three unsuccessful attempts were made on his life.

When the Congress Party chose to contest elections and accept power under the Federation scheme, Gandhi decided to resign from party membership. He did not disagree with the party's move, but felt that if he resigned, his popularity with Indians would cease to stifle the party's membership, that actually varied from communists, socialists, trade unionists, students, religious conservatives, to those with pro-business convictions and that these various voices would get a chance to make themselves heard. Gandhi also did not want to prove a target for Raj propaganda by leading a party that had temporarily accepted political accommodation with the Raj.[15]

Gandhi returned to the head in 1936, with the Nehru presidency and the Lucknow session of the Congress. Although Gandhi desired a total focus on the task of winning independence and not speculation about India's future, he did not restrain the Congress from adopting socialism as its goal. Gandhi had a clash with Subhas Bose, who had been elected to the presidency in 1938. Gandhi's main points of contention with Bose were his lack of commitment to democracy, and lack of faith in non-violence. Bose won his second term despite Gandhi's criticism, but left the Congress when the All-India leaders resigned en masse in protest against his abandonment of the principles introduced by Gandhi.[16]

World War II and Quit India

World War II broke out in 1939 when Nazi Germany invaded Poland. Initially, Gandhi had favored offering "non-violent moral support" to the British effort, but other Congressional leaders were offended by the unilateral inclusion of India into the war, without consultation of the people's representatives. All Congressmen elected to resign from office en masse.[17] After lengthy deliberations, Gandhi declared that India could not be party to a war ostensibly being fought for democratic freedom, while that freedom was denied to India itself. As the war progressed, Gandhi intensified his demand for independence, drafting a resolution calling for the British to Quit India. This was Gandhi's and the Congress Party's most definitive revolt aimed at securing the British exit from Indian shores.[18]

Gandhi was criticized by some Congress party members and other Indian political groups, both pro-British and anti-British. Some felt that opposing Britain in its life or death struggle was immoral, and others felt that Gandhi wasn't doing enough. Quit India became the most forceful movement in the history of the struggle, with mass arrests and violence on an unprecedented scale.[19] Thousands of freedom fighters were killed or injured by police gunfire, and hundreds of thousands were arrested. Gandhi and his supporters made it clear they would not support the war effort unless India were granted immediate independence. He even clarified that this time the movement would not be stopped if individual acts of violence were committed, saying that the "ordered anarchy" around him was "worse than real anarchy." He called on all Congressmen and Indians to maintain discipline via ahimsa, and Karo Ya Maro ("Do or Die") in the cause of ultimate freedom.

Gandhi and the entire Congress Working Committee were arrested in Mumbai by the British on 9 August 1942. Gandhi was held for two years in the Aga Khan Palace in Pune. It was here that Gandhi suffered two terrible blows in his personal life. His 50-year old secretary Mahadev Desai died of a heart attack 6 days later and his wife Kasturba died after 18 months imprisonment in 22 February 1944; six weeks later Gandhi suffered a severe malaria attack. He was released before the end of the war on 6 May 1944 because of his failing health and necessary surgery; the Raj did not want him to die in prison and enrage the nation. Although the Quit India movement had moderate success in its objective, the ruthless suppression of the movement brought order to India by the end of 1943. At the end of the war, the British gave clear indications that power would be transferred to Indian hands. At this point Gandhi called off the struggle, and around 100,000 political prisoners were released, including the Congress's leadership.

Freedom and partition of India

Gandhi advised the Congress to reject the proposals the British Cabinet Mission offered in 1946, as he was deeply suspicious of the grouping proposed for Muslim-majority states—Gandhi viewed this as a precursor to partition. However, this became one of the few times the Congress broke from Gandhi's advice (though not his leadership), as Nehru and Patel knew that if the Congress did not approve the plan, the control of government would pass to the Muslim League. Between 1946 and 1948, over 5,000 people were killed in violence. Gandhi was vehemently opposed to any plan that partitioned India into two separate countries. An overwhelming majority of Muslims living in India, side by side with Hindus and Sikhs, were in favour of Partition. Additionally Muhammad Ali Jinnah, the leader of the Muslim League, commanded widespread support in West Punjab, Sindh, North-West Frontier Province and East Bengal. The partition plan was approved by the Congress leadership as the only way to prevent a wide-scale Hindu-Muslim civil war. Congress leaders knew that Gandhi would viscerally oppose partition, and it was impossible for the Congress to go ahead without his agreement, for Gandhi's support in the party and throughout India was strong. Gandhi's closest colleagues had accepted partition as the best way out, and Sardar Patel endeavoured to convince Gandhi that it was the only way to avoid civil war. A devastated Gandhi gave his assent.

He conducted extensive dialogue with Muslim and Hindu community leaders, working to cool passions in northern India, as well as in Bengal. Despite the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947, he was troubled when the Government decided to deny Pakistan the Rs. 55 crores due as per agreements made by the Partition Council. Leaders like Sardar Patel feared that Pakistan would use the money to bankroll the war against India. Gandhi was also devastated when demands resurged for all Muslims to be deported to Pakistan, and when Muslim and Hindu leaders expressed frustration and an inability to come to terms with one another.[20] He launched his last fast-unto-death in Delhi, asking that all communal violence be ended once and for all, and that the payment of Rs. 55 crores be made to Pakistan. Gandhi feared that instability and insecurity in Pakistan would increase their anger against India, and violence would spread across the borders. He further feared that Hindus and Muslims would renew their enmity and precipitate into an open civil war. After emotional debates with his life-long colleagues, Gandhi refused to budge, and the Government rescinded its policy and made the payment to Pakistan. Hindu, Muslim and Sikh community leaders, including the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh and Hindu Mahasabha assured him that they would renounce violence and call for peace. Gandhi thus broke his fast by sipping orange juice.[21]

Assassination

- See also: Assassination of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi

On 30 January 1948, Gandhi was shot and killed while having his nightly public walk on the grounds of the Birla Bhavan (Birla House) in New Delhi. The assassin, Nathuram Godse, was a Hindu radical with links to the extremist Hindu Mahasabha, who held Gandhi responsible for weakening India by insisting upon a payment to Pakistan.[22] Godse and his co-conspirator Narayan Apte were later tried and convicted; they were executed on 15 November 1949. Gandhi's memorial (or Samādhi) at Rāj Ghāt, New Delhi, bears the epigraph "Hē Ram", (Devanagari: हे ! राम or, He Rām), which may be translated as "Oh God". These are widely believed to be Gandhi's last words after he was shot, though the veracity of this statement has been disputed.[23] Jawaharlal Nehru addressed the nation through radio:

| “ | Friends and comrades, the light has gone out of our lives, and there is darkness everywhere, and I do not quite know what to tell you or how to say it. Our beloved leader, Bapu as we called him, the father of the nation, is no more. Perhaps I am wrong to say that; nevertheless, we will not see him again, as we have seen him for these many years, we will not run to him for advice or seek solace from him, and that is a terrible blow, not only for me, but for millions and millions in this country.[24] | ” |

Gandhi's ashes were poured into urns which were sent across India for memorial services. Most were immersed at the Sangam at Allahabad on 12 February 1948 but some were secreted away.[25] In 1997, Tushar Gandhi immersed the contents of one urn, found in a bank vault and reclaimed through the courts, at the Sangam at Allahabad.[25][26] On 30 January 2008 the contents of another urn were immersed at Girgaum Chowpatty by the family after a Dubai-based businessman had sent it to a Mumbai museum.[25] Another urn has ended up in a palace of the Aga Khan in Pune[25] (where he had been imprisoned from 1942 to 1944) and another in the Self-Realization Fellowship Lake Shrine in Los Angeles.[27] The family is aware that these enshrined ashes could be misused for political purposes but does not want to have them removed because it would entail breaking the shrines.[25]

Gandhi's principles

- See also: Gandhism

Truth

Gandhi dedicated his life to the wider purpose of discovering truth, or Satya. He tried to achieve this by learning from his own mistakes and conducting experiments on himself. He called his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth.

Gandhi stated that the most important battle to fight was overcoming his own demons, fears, and insecurities. Gandhi summarized his beliefs first when he said "God is Truth". He would later change this statement to "Truth is God". Thus, Satya (Truth) in Gandhi's philosophy is "God".

Nonviolence

Although Mahatama Gandhi was in no way the originator of the principle of non-violence, he was the first to apply it in the political field on a huge scale.[28] The concept of nonviolence (ahimsa) and nonresistance has a long history in Indian religious thought and has had many revivals in Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, Jewish and Christian contexts. Gandhi explains his philosophy and way of life in his autobiography The Story of My Experiments with Truth. He was quoted as saying:

"When I despair, I remember that all through history the way of truth and love has always won. There have been tyrants and murderers and for a time they seem invincible, but in the end, they always fall — think of it, always."

"What difference does it make to the dead, the orphans, and the homeless, whether the mad destruction is wrought under the name of totalitarianism or the holy name of liberty and democracy?"

"An eye for an eye makes the whole world blind."

"There are many causes that I am prepared to die for but no causes that I am prepared to kill for."

In applying these principles, Gandhi did not balk from taking them to their most logical extremes in envisioning a world where even government, police and armies were nonviolent. The quotations below are from the book "For Pacifists."[29]

The science of war leads one to dictatorship, pure and simple. The science of non-violence alone can lead one to pure democracy...Power based on love is thousand times more effective and permanent than power derived from fear of punishment....It is a blasphemy to say non-violence can be practiced only by individuals and never by nations which are composed of individuals...The nearest approach to purest anarchy would be a democracy based on non-violence...A society organized and run on the basis of complete non-violence would be the purest anarchy

I have conceded that even in a non-violent state a police force may be necessary...Police ranks will be composed of believers in non-violence. The people will instinctively render them every help and through mutual cooperation they will easily deal with the ever decreasing disturbances...Violent quarrels between labor and capital and strikes will be few and far between in a non-violent state because the influence of the non-violent majority will be great as to respect the principle elements in society. Similarly, there will be no room for communal disturbances....

A non-violent army acts unlike armed men, as well in times of peace as in times of disturbances. Theirs will be the duty of bringing warring communities together, carrying peace propaganda, engaging in activities that would bring and keep them in touch with every single person in their parish or division. Such an army should be ready to cope with any emergency, and in order to still the frenzy of mobs should risk their lives in numbers sufficient for that purpose. ...Satyagraha (truth-force) brigades can be organized in every village and every block of buildings in the cities. [If the non-violent society is attacked from without] there are two ways open to non-violence. To yield possession, but non-cooperate with the aggressor...prefer death to submission. The second way would be non-violent resistance by the people who have been trained in the non-violent way...The unexpected spectacle of endless rows upon rows of men and women simply dying rather than surrender to the will of an aggressor must ultimately melt him and his soldiery...A nation or group which has made non-violence its final policy cannot be subjected to slavery even by the atom bomb.... The level of non-violence in that nation, if that even happily comes to pass, will naturally have risen so high as to command universal respect.

In accordance with these views, in 1940, when invasion of the British Isles by Nazi Germany looked imminent, Gandhi offered the following advice to the British people (Non-Violence in Peace and War):[30]

"I would like you to lay down the arms you have as being useless for saving you or humanity. You will invite Herr Hitler and Signor Mussolini to take what they want of the countries you call your possessions...If these gentlemen choose to occupy your homes, you will vacate them. If they do not give you free passage out, you will allow yourselves, man, woman, and child, to be slaughtered, but you will refuse to owe allegiance to them."

In a post-war interview in 1946, he offered a view at an even further extreme:

"The Jews should have offered themselves to the butcher's knife. They should have thrown themselves into the sea from cliffs."

However, Gandhi was aware that this level of nonviolence required incredible faith and courage, which he realized not everyone possessed. He therefore advised that everyone need not keep to nonviolence, especially if it were used as a cover for cowardice:

"Gandhi guarded against attracting to his satyagraha movement those who feared to take up arms or felt themselves incapable of resistance. 'I do believe,' he wrote, 'that where there is only a choice between cowardice and violence, I would advise violence.'"[31]

"At every meeting I repeated the warning that unless they felt that in non-violence they had come into possession of a force infinitely superior to the one they had and in the use of which they were adept, they should have nothing to do with non-violence and resume the arms they possessed before. It must never be said of the Khudai Khidmatgars that once so brave, they had become or been made cowards under Badshah Khan's influence. Their bravery consisted not in being good marksmen but in defying death and being ever ready to bare their breasts to the bullets."[32]

Vegetarianism

As a young child, Gandhi experimented with meat-eating. This was due partially to his inherent curiosity as well as his rather persuasive peer and friend Sheikh Mehtab. The idea of vegetarianism is deeply ingrained in Hindu and Jain traditions in India, and, in his native land of Gujarat, most Hindus were vegetarian and so are all Jains. The Gandhi family was no exception. Before leaving for his studies in London, Gandhi made a promise to his mother, Putlibai and his uncle, Becharji Swami that he would abstain from eating meat, taking alcohol, and engaging in promiscuity. He held fast to his promise and gained more than a diet: he gained a basis for his life-long philosophies. As Gandhi grew into adulthood, he became a strict vegetarian. He wrote the book The Moral Basis of Vegetarianism and several articles on the subject, some of which were published in the London Vegetarian Society's publication, The Vegetarian.[33] Gandhi, himself, became inspired by many great minds during this period and befriended the chairman of the London Vegetarian Society, Dr. Josiah Oldfield.

Having also read and admired the work of Henry Stephens Salt, the young Mohandas met and often corresponded with the vegetarian campaigner. Gandhi spent much time advocating vegetarianism during and after his time in London. To Gandhi, a vegetarian diet would not only satisfy the requirements of the body, it would also serve an economic purpose as meat was, and still is, generally more expensive than grains, vegetables, and fruits. Also, many Indians of the time struggled with low income, thus vegetarianism was seen not only as a spiritual practice but also a practical one. He abstained from eating for long periods, using fasting as a form of political protest. He refused to eat until his death or his demands were met. It was noted in his autobiography that vegetarianism was the beginning of his deep commitment to Brahmacharya; without total control of the palate, his success in Bramacharya would likely falter.

Gandhi had been a frutarian,[34] but started taking goat's milk on the advice of his doctor. He never took dairy products obtained from cows because of his view initially that milk is not the natural diet of man, disgust for cow blowing,[35] and, specifically, because of a vow to his late mother.

Brahmacharya

When Gandhi was 16 his father became very ill. Being very devoted to his parents, he attended to his father at all times during his illness. However, one night, Gandhi's uncle came to relieve Gandhi for a while. He retired to his bedroom where carnal desires overcame him and he made love to his wife. Shortly afterward a servant came to report that Gandhi's father had just died. Gandhi felt tremendous guilt and never could forgive himself. He came to refer to this event as "double shame." The incident had significant influence in Gandhi becoming celibate at the age of 36, while still married.[36]

This decision was deeply influenced by the philosophy of Brahmacharya — spiritual and practical purity — largely associated with celibacy and asceticism. Gandhi saw Brahmacharya as a means of becoming close with God and as a primary foundation for self realization. In his autobiography he tells of his battle against lustful urges and fits of jealousy with his childhood bride, Kasturba. He felt it his personal obligation to remain celibate so that he could learn to love, rather than lust. For Gandhi, Brahmacharya meant "control of the senses in thought, word and deed."[37]

Experiments with Brahmacharya

Towards the end of his life, it became public knowledge that Gandhi had been sharing his bed for a number of years with young women.[38][39] He explained that he did this for bodily warmth at night and termed his actions as "nature cure". Later in his life he started experimenting with Brahmacharya in order to test his self control. His letter to Birla in April, 1945 referring to ‘women or girls who have been naked with me’ indicates that several women were part of his experiments.[40] Sex became the most talked about subject matter by Gandhi after ahimsa (non-violence) and increasingly so in his later years. He devoted five full editorials in Harijan discussing the practice of Brahmacharya.[41]

As part of these experiments, he initially slept with his women associates in the same room but at a distance. Afterwards he started to lie in the same bed with his women disciples and later took to sleeping naked alongside them.[40] According to Gandhi active-celibacy meant perfect self control in the presence of opposite sex. Gandhi conducted his experiments with a number of women such as Abha, the sixteen-year-old wife of his grandnephew Kanu Gandhi. Gandhi acknowledged “that this experiment is very dangerous indeed”, but thought “that it was capable of yielding great results”.[42] His nineteen-year-old grandniece, Manu Gandhi, too was part of his experiments. Gandhi had earlier written to her father, Jaisukhlal Gandhi, that Manu had started to share his bed so that he may "correct her sleeping posture".[42] In Gandhi’s view, the experiment of sleeping naked with Manu in Noakhali would help him in contemplating upon Hindu-Muslim unity in India before partition and ease communal tensions. Gandhi saw himself as a mother to these women and would refer to Abha and Manu as “my walking sticks”.

Gandhi called Sarladevi, a married woman with children and a devout follower, his “spiritual wife”. He later said that he had come close to having sexual relations with her.[43] He had told a correspondent in March, 1945 that “sleeping together came with my taking up of bramhacharya or even before that”; he said he had experimented with his wife “but that was not enough”.[42] Gandhi felt satisfied with his experiments and wrote to Manu that “I have successfully practiced the eleven vows taken by me. This is the culmination of my striving for last thirty six years. In this yajna I got a glimpse of the ideal truth and purity for which I have been striving”.

Gandhi had to take criticism for his experiments by many of his followers and opponents. His stenographer, R. P. Parasuram, resigned when he saw Gandhi sleeping naked with Manu.[44] Gandhi insisted that he never felt aroused while he slept beside her, or with Sushila or Abha. "I am sorry" Gandhi said to Parasuram, "you are at liberty to leave me today." Nirmal Kumar Bose, another close associate of Gandhi, parted company with him in April 1947, post Gandhi's tour of Noakhali, where some sort of altercation had taken place between Gandhi and Sushila Nayar in his bedroom at midnight that caused Gandhi to slap his forehead. Bose had stated that the nature of his experiments in Bramhacharya still remained unknown and unstated.[44][45]

N. K. Bose, who stayed close to Gandhi during his Noakhali tour, testified that “there was no immorality on part of Gandhi. Moreover Gandhi tried to conquer the feeling of sex by consciously endeavouring to convert himself into a mother of those who were under his care, whether men or women”. Dattatreya Balkrishna Kalelkar, a revolutionary turned disciple of Gandhi, used to say that Gandhi’s “relationships with women were, from beginning to end, as pure as mother’s milk”.[46]

Simplicity

Gandhi earnestly believed that a person involved in social service should lead a simple life which he thought could lead to Brahmacharya. His simplicity began by renouncing the western lifestyle he was leading in South Africa. He called it "reducing himself to zero," which entailed giving up unnecessary expenditure, embracing a simple lifestyle and washing his own clothes.[47] On one occasion he returned the gifts bestowed to him from the natals for his diligent service to the community.[48]

Gandhi spent one day of each week in silence. He believed that abstaining from speaking brought him inner peace. This influence was drawn from the Hindu principles of mauna (Sanskrit:मौनं — silence) and shanti (Sanskrit:शांति — peace). On such days he communicated with others by writing on paper. For three and a half years, from the age of 37, Gandhi refused to read newspapers, claiming that the tumultuous state of world affairs caused him more confusion than his own inner unrest.

After reading John Ruskin's Unto This Last, he decided to change his lifestyle and create a commune called Phoenix Settlement.

Upon returning to India from South Africa, where he had enjoyed a successful legal practice, he gave up wearing Western-style clothing, which he associated with wealth and success. He dressed to be accepted by the poorest person in India, advocating the use of homespun cloth (khadi). Gandhi and his followers adopted the practice of weaving their own clothes from thread they themselves spun, and encouraged others to do so. While Indian workers were often idle due to unemployment, they had often bought their clothing from industrial manufacturers owned by British interests. It was Gandhi's view that if Indians made their own clothes, it would deal an economic blow to the British establishment in India. Consequently, the spinning wheel was later incorporated into the flag of the Indian National Congress. He subsequently wore a dhoti for the rest of his life to express the simplicity of his life.

Faith

Gandhi was born a Hindu and practised Hinduism all his life, deriving most of his principles from Hinduism. As a common Hindu, he believed all religions to be equal, and rejected all efforts to convert him to a different faith. He was an avid theologian and read extensively about all major religions. He had the following to say about Hinduism:

- "Hinduism as I know it entirely satisfies my soul, fills my whole being...When doubts haunt me, when disappointments stare me in the face, and when I see not one ray of light on the horizon, I turn to the Bhagavad Gita, and find a verse to comfort me; and I immediately begin to smile in the midst of overwhelming sorrow. My life has been full of tragedies and if they have not left any visible and indelible effect on me, I owe it to the teachings of the Bhagavad Gita."

Gandhi wrote a commentary on the Bhagavad Gita in Gujarati. The Gujarati manuscript was translated into English by Mahadev Desai, who provided an additional introduction and commentary. It was published with a Foreword by Gandhi in 1946.[49][50]

Gandhi believed that at the core of every religion was truth and love (compassion, nonviolence and the Golden Rule). He also questioned hypocrisy, malpractices and dogma in all religions and was a tireless social reformer. Some of his comments on various religions are:

- "Thus if I could not accept Christianity either as a perfect, or the greatest religion, neither was I then convinced of Hinduism being such. Hindu defects were pressingly visible to me. If untouchability could be a part of Hinduism, it could but be a rotten part or an excrescence. I could not understand the raison d'etre of a multitude of sects and castes. What was the meaning of saying that the Vedas were the inspired Word of God? If they were inspired, why not also the Bible and the Koran? As Christian friends were endeavouring to convert me, so were Muslim friends. Abdullah Sheth had kept on inducing me to study Islam, and of course he had always something to say regarding its beauty." (source: his autobiography)

- "As soon as we lose the moral basis, we cease to be religious. There is no such thing as religion over-riding morality. Man, for instance, cannot be untruthful, cruel or incontinent and claim to have God on his side."

- "The sayings of Muhammad are a treasure of wisdom, not only for Muslims but for all of mankind."

Later in his life when he was asked whether he was a Hindu, he replied:

- "Yes I am. I am also a Christian, a Muslim, a Buddhist and a Jew."

In spite of their deep reverence to each other, Gandhi and Rabindranath Tagore engaged in protracted debates more than once. These debates exemplify the philosophical differences between the two most famous Indians at the time. On 15 January 1934, an earthquake hit Bihar and caused extensive damage and loss of life. Gandhi maintained this was because of the sin committed by upper caste Hindus by not letting untouchables in their temples (Gandhi was committed to the cause of improving the fate of untouchables, referring to them as Harijans, people of Krishna). Tagore vehemently opposed Gandhi's stance, maintaining that an earthquake can only be caused by natural forces, not moral reasons, however repugnant the practice of untouchability may be.[51]

Writings

Gandhi was a prolific writer. For decades he edited several newspapers including Harijan in Gujarati, Hindi and English; Indian Opinion while in South Africa and, Young India, in English, and Navajivan, a Gujarati monthly, on his return to India. Later Navajivan was also published in Hindi.[52] In addition, he wrote letters almost every day to individuals and newspapers.

Gandhi also wrote a few books including his autobiography, An Autobiography or My Experiments with Truth, Satyagraha in South Africa about his struggle there, Hind Swaraj or Indian Home Rule, a political pamphlet, and a paraphrase in Gujarati of John Ruskin's Unto This Last.[53] This last essay can be considered his program on economics. He also wrote extensively on vegetarianism, diet and health, religion, social reforms, etc. Gandhi usually wrote in Gujarati, though he also revised the Hindi and English translations of his books.

Gandhi's complete works were published by the Indian government under the name The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi in the 1960s. The writings comprise about 50,000 pages published in about a hundred volumes. In 2000, a revised edition of the complete works sparked a controversy, as Gandhian followers argue that the government incorporated the changes for political purposes.[54]

Books on Gandhi

Several biographers have undertaken the task of describing Gandhi's life. Among them, two works stand out: D. G. Tendulkar with his Mahatma. Life of Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi in eight volumes, and Pyarelal and Sushila Nayar with their Mahatma Gandhi in 10 volumes. Colonel G. B. Singh from the US Army wrote the book Gandhi: Behind the Mask of Divinity[55]. In the book, G. B. Singh argues that much of the existing Gandhi literature has promulgated from Gandhi's own autobiographies and there is little critical review of Gandhi's words and actions. In his thesis built on Gandhi's own words, letters and newspapers columns and his actions, Singh argues that that Gandhi had a racial dislike for the native black Africans and later against the white British in India. Singh's later work with Dr. Tim Watson called Gandhi Under Cross Examination(2008) argues that Gandhi himself gave various varying accounts of the famous train incident in South Africa and the authors argue that this incident did not happen as understood today.

Followers and influence

| “ | Christ gave us the goals and Mahatma Gandhi the tactics. | ” |

|

— Martin Luther King Jr, 1955[56]

|

Gandhi influenced important leaders and political movements. Leaders of the civil rights movement in the United States, including Martin Luther King and James Lawson, drew from the writings of Gandhi in the development of their own theories about non-violence.[57] Anti-apartheid activist and former President of South Africa, Nelson Mandela, was inspired by Gandhi.[58] Others include Khan Abdul Ghaffar Khan,[59] Steve Biko, and Aung San Suu Kyi.[60]

Gandhi's life and teachings inspired many who specifically referred to Gandhi as their mentor or who dedicated their lives to spreading Gandhi's ideas. In Europe, Romain Rolland was the first to discuss Gandhi in his 1924 book Mahatma Gandhi, and Brazilian anarchist and feminist Maria Lacerda de Moura wrote about Gandhi in her work on pacifism. In 1931, notable European physicist Albert Einstein exchanged written letters with Gandhi, and called him "a role model for the generations to come" in a later writing about him.[61] Lanza del Vasto went to India in 1936 intending to live with Gandhi; he later returned to Europe to spread Gandhi's philosophy and founded the Community of the Ark in 1948 (modeled after Gandhi's ashrams). Madeleine Slade (known as "Mirabehn") was the daughter of a British admiral who spent much of her adult life in India as a devotee of Gandhi.

In addition, the British musician John Lennon referred to Gandhi when discussing his views on non-violence.[62] At the Cannes Lions International Advertising Festival in 2007, former U.S. Vice-President and environmentalist Al Gore spoke of Gandhi's influence on him.[63]

Legacy

Gandhi's birthday, 2 October, is a national holiday in India, Gandhi Jayanti. On 15 June 2007, it was announced that the "United Nations General Assembly" has "unanimously adopted" a resolution declaring 2 October as "the International Day of Non-Violence."[64]

The word Mahatma, while often mistaken for Gandhi's given name in the West, is taken from the Sanskrit words maha meaning Great and atma meaning Soul. Most sources, such as Dutta and Robinson's Rabindranath Tagore: An Anthology, state that Rabindranath Tagore first accorded the title of Mahatma to Gandhi.[65] Other sources state that Nautamlal Bhagavanji Mehta accorded him this title on 21 January 1915.[66] In his autobiography, Gandhi nevertheless explains that he never felt worthy of the honour.[67] According to the manpatra, the name Mahatma was given in response to Gandhi's admirable sacrifice in manifesting justice and truth.[68]

Time magazine named Gandhi the Man of the Year in 1930. Gandhi was also the runner-up to Albert Einstein as "Person of the Century" at the end of 1999. Time Magazine named The Dalai Lama, Lech Wałęsa, Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr., Cesar Chavez, Aung San Suu Kyi, Benigno Aquino, Jr., Desmond Tutu, and Nelson Mandela as Children of Gandhi and his spiritual heirs to non-violence.[69] The Government of India awards the annual Mahatma Gandhi Peace Prize to distinguished social workers, world leaders and citizens. Nelson Mandela, the leader of South Africa's struggle to eradicate racial discrimination and segregation, is a prominent non-Indian recipient.

In 1996, the Government of India introduced the Mahatma Gandhi series of currency notes in rupees 5, 10, 20, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 denomination. Today, all the currency notes in circulation in India contain a portrait of Mahatma Gandhi. In 1969, the United Kingdom issued a series of stamps commemorating the centenary of Mahatma Gandhi.

In the United Kingdom, there are several prominent statues of Gandhi, most notably in Tavistock Square, London near University College London where he studied law. 30 January is commemorated in the United Kingdom as the "National Gandhi Remembrance Day." In the United States, there are statues of Gandhi outside the Union Square Park in New York City, and the Martin Luther King, Jr. National Historic Site in Atlanta, and on Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, D.C., near the Indian Embassy. The city of Pietermaritzburg, South Africa—where Gandhi was ejected from a first-class train in 1893—now hosts a commemorative statue. There are wax statues of Gandhi at the Madame Tussaud's wax museums in London, New York, and other cities around the world.

Gandhi never received the Nobel Peace Prize, although he was nominated five times between 1937 and 1948, including the first-ever nomination by the American Friends Service Committee.[70] Decades later, the Nobel Committee publicly declared its regret for the omission, and admitted to deeply divided nationalistic opinion denying the award. Mahatma Gandhi was to receive the Prize in 1948, but his assassination prevented the award. The war breaking out between the newly created states of India and Pakistan could have been an additional complicating factor that year.[71] The Prize was not awarded in 1948, the year of Gandhi's death, on the grounds that "there was no suitable living candidate" that year, and when the Dalai Lama was awarded the Prize in 1989, the chairman of the committee said that this was "in part a tribute to the memory of Mahatma Gandhi."[72]

In New Delhi, the Birla Bhavan (or Birla House), where Gandhi was assassinated on 30 January 1948, was acquired by the Government of India in 1971 and opened to the public in 1973 as the Gandhi Smriti or "Gandhi Remembrance". It preserves the room where Mahatma Gandhi lived the last four months of his life and the grounds where he was shot while holding his nightly public walk. A Martyr's Column now marks the place where Mohandas Gandhi was assassinated.

On 30 January every year, on the anniversary of the death of Mahatma Gandhi, in schools of many countries is observed the School Day of Non-violence and Peace (DENIP), founded in Spain in 1964. In countries with a Southern Hemisphere school calendar, it can be observed on 30 March or thereabouts.

Ideals and criticisms

Gandhi's rigid ahimsa implies pacifism, and is thus a source of criticism from across the political spectrum.

Concept of partition

As a rule, Gandhi was opposed to the concept of partition as it contradicted his vision of religious unity.[73] Of the partition of India to create Pakistan, he wrote in Harijan on 6 October 1946:

[The demand for Pakistan] as put forth by the Moslem League is un-Islamic and I have not hesitated to call it sinful. Islam stands for unity and the brotherhood of mankind, not for disrupting the oneness of the human family. Therefore, those who want to divide India into possibly warring groups are enemies alike of India and Islam. They may cut me into pieces but they cannot make me subscribe to something which I consider to be wrong [...] we must not cease to aspire, in spite of [the] wild talk, to befriend all Moslems and hold them fast as prisoners of our love.[74]

However, as Homer Jack notes of Gandhi's long correspondence with Jinnah on the topic of Pakistan: "Although Gandhi was personally opposed to the partition of India, he proposed an agreement...which provided that the Congress and the Moslem League would cooperate to attain independence under a provisional government, after which the question of partition would be decided by a plebiscite in the districts having a Moslem majority."[75]

These dual positions on the topic of the partition of India opened Gandhi up to criticism from both Hindus and Muslims. Muhammad Ali Jinnah and contemporary Pakistanis condemned Gandhi for undermining Muslim political rights. Vinayak Damodar Savarkar and his allies condemned Gandhi, accusing him of politically appeasing Muslims while turning a blind eye to their atrocities against Hindus, and for allowing the creation of Pakistan (despite having publicly declared that "before partitioning India, my body will have to be cut into two pieces").[76] This continues to be politically contentious: some, like Pakistani-American historian Ayesha Jalal argue that Gandhi and the Congress' unwillingness to share power with the Muslim League hastened partition; others, like Hindu nationalist politician Pravin Togadia have also criticized Gandhi's leadership and actions on this topic, but indicating that excessive weakeness on his part led to the division of India.

Gandhi also expressed his dislike for partition during the late 1930s in response to the topic of the partition of Palestine to create Israel. He stated in Harijan on 26 October 1938:

Several letters have been received by me asking me to declare my views about the Arab-Jew question in Palestine and persecution of the Jews in Germany. It is not without hesitation that I venture to offer my views on this very difficult question. My sympathies are all with the Jews. I have known them intimately in South Africa. Some of them became life-long companions. Through these friends I came to learn much of their age-long persecution. They have been the untouchables of Christianity [...] But my sympathy does not blind me to the requirements of justice. The cry for the national home for the Jews does not make much appeal to me. The sanction for it is sought in the Bible and the tenacity with which the Jews have hankered after return to Palestine. Why should they not, like other peoples of the earth, make that country their home where they are born and where they earn their livelihood? Palestine belongs to the Arabs in the same sense that England belongs to the English or France to the French. It is wrong and inhuman to impose the Jews on the Arabs. What is going on in Palestine today cannot be justified by any moral code of conduct.[77][78]

Rejection of violent resistance

Gandhi also came under some political fire for his criticism of those who attempted to achieve independence through more violent means. His refusal to protest against the hanging of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev, Udham Singh and Rajguru were sources of condemnation among some parties.[79][80]

Of this criticism, Gandhi stated, "There was a time when people listened to me because I showed them how to give fight to the British without arms when they had no arms...but today I am told that my non-violence can be of no avail against the [Hindu–Moslem riots] and, therefore, people should arm themselves for self-defense."[81]

He continued this argument in a number of articles reprinted in Homer Jack's The Gandhi Reader: A Sourcebook of His Life and Writings. In the first, "Zionism and Anti-Semitism," written in 1938, Gandhi commented upon the 1930s persecution of the Jews in Germany within the context of Satyagraha. He offered non-violence as a method of combating the difficulties Jews faced in Germany, stating,

If I were a Jew and were born in Germany and earned my livelihood there, I would claim Germany as my home even as the tallest Gentile German might, and challenge him to shoot me or cast me in the dungeon; I would refuse to be expelled or to submit to discriminating treatment. And for doing this I should not wait for the fellow Jews to join me in civil resistance, but would have confidence that in the end the rest were bound to follow my example. If one Jew or all the Jews were to accept the prescription here offered, he or they cannot be worse off than now. And suffering voluntarily undergone will bring them an inner strength and joy...the calculated violence of Hitler may even result in a general massacre of the Jews by way of his first answer to the declaration of such hostilities. But if the Jewish mind could be prepared for voluntary suffering, even the massacre I have imagined could be turned into a day of thanksgiving and joy that Jehovah had wrought deliverance of the race even at the hands of the tyrant. For to the God-fearing, death has no terror.[82]

Gandhi was highly criticized for these statements and responded in the article "Questions on the Jews" with "Friends have sent me two newspaper cuttings criticizing my appeal to the Jews. The two critics suggest that in presenting non-violence to the Jews as a remedy against the wrong done to them, I have suggested nothing new...what I have pleaded for is renunciation of violence of the heart and consequent active exercise of the force generated by the great renunciation.[83] He responded to the criticisms in "Reply to Jewish Friends"[84] and "Jews and Palestine."[85] by arguing that "What I have pleaded for is renunciation of violence of the heart and consequent active exercise of the force generated by the great renunciation."[83]

Gandhi's statements regarding Jews facing the impending Holocaust have attracted criticism from a number of commentators.[86] Martin Buber, himself an opponent of a Jewish state, wrote a sharply critical open letter to Gandhi on 24 February 1939. Buber asserted that the comparison between British treatment of Indian subjects and Nazi treatment of Jews was inapposite; moreover, he noted that when Indians were the victims of persecution, Gandhi had, on occasion, supported the use of force.[87]

Gandhi commented upon the 1930s persecution of the Jews in Germany within the context of Satyagraha. In the November 1938 article on the Nazi persecution of the Jews quoted above, he offered non-violence as a solution:

The German persecution of the Jews seems to have no parallel in history. The tyrants of old never went so mad as Hitler seems to have gone. And he is doing it with religious zeal. For he is propounding a new religion of exclusive and militant nationalism in the name of which any inhumanity becomes an act of humanity to be rewarded here and hereafter. The crime of an obviously mad but intrepid youth is being visited upon his whole race with unbelievable ferocity. If there ever could be a justifiable war in the name of and for humanity, a war against Germany, to prevent the wanton persecution of a whole race, would be completely justified. But I do not believe in any war. A discussion of the pros and cons of such a war is therefore outside my horizon or province. But if there can be no war against Germany, even for such a crime as is being committed against the Jews, surely there can be no alliance with Germany. How can there be alliance between a nation which claims to stand for justice and democracy and one which is the declared enemy of both?"[88][89]

Early South African articles

Some of Gandhi's early South African articles are controversial. On 7 March 1908, Gandhi wrote in the Indian Opinion of his time in a South African prison: "Kaffirs are as a rule uncivilised - the convicts even more so. They are troublesome, very dirty and live almost like animals."[90] Writing on the subject of immigration in 1903, Gandhi commented: "We believe as much in the purity of race as we think they do... We believe also that the white race in South Africa should be the predominating race."[91] During his time in South Africa, Gandhi protested repeatedly about the social classification of blacks with Indians, who he described as "undoubtedly infinitely superior to the Kaffirs".[92] It is worth noting that during Gandhi's time, the term Kaffir had a different connotation than its present-day usage. Remarks such as these have led some to accuse Gandhi of racism.[93]

Two professors of history who specialize in South Africa, Surendra Bhana and Goolam Vahed, examined this controversy in their text, The Making of a Political Reformer: Gandhi in South Africa, 1893–1914. (New Delhi: Manohar, 2005).[94] They focus in Chapter 1, "Gandhi, Africans and Indians in Colonial Natal" on the relationship between the African and Indian communities under "White rule" and policies which enforced segregation (and, they argue, inevitable conflict between these communities). Of this relationship they state that, "the young Gandhi was influenced by segregationist notions prevalent in the 1890s."[95] At the same time, they state, "Gandhi's experiences in jail seemed to make him more sensitive to their plight...the later Gandhi mellowed; he seemed much less categorical in his expression of prejudice against Africans, and much more open to seeing points of common cause. His negative views in the Johannesburg jail were reserved for hardened African prisoners rather than Africans generally."[96]

Former President of South Africa Nelson Mandela is a follower of Gandhi,[58] despite efforts in 2003 on the part of Gandhi's critics to prevent the unveiling of a statue of Gandhi in Johannesburg.[93] Bhana and Vahed commented on the events surrounding the unveiling in the conclusion to The Making of a Political Reformer: Gandhi in South Africa, 1893–1914. In the section "Gandhi's Legacy to South Africa," they note that "Gandhi inspired succeeding generations of South African activists seeking to end White rule. This legacy connects him to Nelson Mandela...in a sense Mandela completed what Gandhi started."[97] They continue by referring to the controversies which arose during the unveiling of the statue of Gandhi.[98] In response to these two perspectives of Gandhi, Bhana and Vahed argue: "Those who seek to appropriate Gandhi for political ends in post-apartheid South Africa do not help their cause much by ignoring certain facts about him; and those who simply call him a racist are equally guilty of distortion."[99]

Anti Statism

- See also: Swaraj

Gandhi was an anti statist in the sense that his vision of India meant India without an underlying government.[100] His idea was that true self rule in a country means that every person rules himself and that there is no state which enforces laws upon the people.[101][102] On occasions he described himself as a philosophical anarchist.[103] A free India for him meant existence of thousands of self sufficient small communities (an idea possibly from Tolstoy) who rule themselves without hindering others. It did not mean merely transferring a British established administrative structure into Indian hands which he said was just making Hindustan into Englistan.[104] He wanted to dissolve the Congress Party after independence and establish a system of direct democracy in India,[105] having no faith in the British styled parliamentary system.[104]

See also

- Gandhi Memorial International Foundation

- Gandhi Peace Prize

- List of artistic depictions of Mahatma Gandhi

Notes

- ↑ Gandhi means "grocer" in Gujarati (L. R. Gala, Popular Combined Dictionary, English-English-Gujarati & Gujarati-Gujarati-English, Navneet), or "perfumer" in Hindi (Bhargava's Standard Illustrated Dictionary Hindi-English).

- ↑ Gandhi 1940, pp. 5–7

- ↑ Gandhi 1940, p. 9

- ↑ Gandhi 1940, pp. 20–22

- ↑ Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi Vol 5 Document#393 from Gandhi: Behind the Mask of Divinity p106

- ↑ http://www.gandhism.net/sergeantmajorgandhi.php Sergeant Major Gandhi

- ↑ Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi VOL 5 p 410

- ↑ Gandhi: An Autobiography: The Story of My Experiments with Truth, trans. Mahaved Desai, (Boston, Beacon Press, 1993) p313

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 82.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 89.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 105.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 131.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 172.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 230–32.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 246.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 277–81.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 283–86.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 309.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 318.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 462.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, pp. 464–66.

- ↑ R. Gandhi, Patel: A Life, p. 472.

- ↑ Vinay Lal. ‘Hey Ram’: The Politics of Gandhi’s Last Words. Humanscape 8, no. 1 (January 2001): pp. 34–38.

- ↑ Nehru's address on Gandhi's death. Retrieved on 15 March 2007.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 25.2 25.3 25.4 "Gandhi's ashes to rest at sea, not in a museum" The Guardian, 16 January 2008

- ↑ "GANDHI'S ASHES SCATTERED" The Cincinnati Post, 30 January 1997 "For reasons no one knows, a portion of the ashes was placed in a safe deposit box at a bank in Cuttack, 1,100 miles (1,800 km) southeast of New Delhi. Tushar Gandhi went to court to gain custody of the ashes after newspapers reported in 1995 that they were at the bank."

- ↑ Ferrell, David (2001-09-27). "A Little Serenity in a City of Madness", pp. B 2.

- ↑ Asirvatham, Eddy. Political Theory. S.chand. ISBN 8121903467.

- ↑ Bharatan Kumarappa, Editor, "For Pacifists," by M.K. Gandhi, Navajivan Publishing House, Ahmedabad, India, 1949.

- ↑ Gandhi, Mahatma (1972). Non-violence in peace and war, 1942–[1949]. Garland Publishing. ISBN 0-8240-0375-6.

- ↑ Bondurant, p. 28.

- ↑ Bondurant, p. 139.

- ↑ "International Vegetarian Union — Mohandas K. Gandhi (1869–1948)".

- ↑ Gokhale's Charity, My Experiments with Truth, M.K. Gandhi.

- ↑ The Rowlatt Bills and my Dilemma, My Experiments with Truth, M.K. Gandhi.

- ↑ Time magazine people of the century

- ↑ The Story of My Experiments with Truth — An Autobiography, p. 176.

- ↑ Birkett, Dea; Susanne Hoeber Rudolph, Lloyd I Rudolph. Gandhi: The Traditional Roots of Charisma. Orient Longman. pp. 56. ISBN 0002160056.

- ↑ Caplan, Pat; Patricia Caplan (1987). The Cultural construction of sexuality. Routledge. pp. 278. ISBN 0415040132.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 Parekh, Bhikhu C. (1999). Colonialism, Tradition and Reform: An Analysis of Gandhi's Political Discourse. Sage. pp. 210. ISBN 0761993835.

- ↑ Kumar, Girja (1997). The Book on Trial: Fundamentalism and Censorship in India. Har-Anand Publications. pp. 98. ISBN 8124105251.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 42.2 Tidrick, Kathryn (2007). Gandhi: A Political and Spiritual Life. I.B.Tauris. pp. 302–304. ISBN 1845111664.

- ↑ Tidrick, Kathryn (2007). Gandhi: A Political and Spiritual Life. I.B.Tauris. pp. 160. ISBN 1845111664.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 Wolpert, Stanley (2001). Gandhi's Passion: The Life and Legacy of Mahatma Gandhi. Oxford University Press. pp. 226–227. ISBN 019515634X.

- ↑ Kumar, Girja (1997). The Book on Trial: Fundamentalism and Censorship in India. Har-Anand Publishers. pp. 73–107. ISBN 8124105251.

- ↑ Ghose, Sankar (1991). Mahatma Gandhi. Allied Publishers. pp. 356. ISBN 8170232058.

- ↑ The Story of My Experiments with Truth — An Autobiography, p. 177.

- ↑ The Story of My Experiments with Truth — An Autobiography, p. 183.

- ↑ Desai, Mahadev. The Gospel of Selfless Action, or, The Gita According To Gandhi. (Navajivan Publishing House: Ahmedabad: First Edition 1946). Other editions: 1948, 1951, 1956.

- ↑ A shorter edition, omitting the bulk of Desai's additional commentary, has been published as: Anasaktiyoga: The Gospel of Selfless Action. Jim Rankin, editor. The author is listed as M.K. Gandhi; Mahadev Desai, translator. (Dry Bones Press, San Francisco, 1998) ISBN 1-883938-47-3.

- ↑ http://www.indiatogether.org/2003/may/rvw-gndhtgore.htm Overview of debates between Gandhi and Tagore

- ↑ Peerless Communicator by V.N. Narayanan. Life Positive Plus, October–December 2002

- ↑ Gandhi, M. K. (in English; trans. from Gujarati) (PDF). Unto this Last: A paraphrase. Ahmedabad: Navajivan Publishing House. ISBN 81-7229-076-4. http://wikilivres.info/wiki/Unto_This_Last_%E2%80%94_M._K._Gandhi.

- ↑ Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi (CWMG) Controversy (gandhiserve)

- ↑ "Gandhi Behind the Mask of Divinity". Retrieved on 2007-12-17.

- ↑ Life Magazine: Remembering Martin Luther King Jr. 40 Years Later. Time Inc, 2008. Pg 12

- ↑ COMMEMORATING MARTIN LUTHER KING JR.: Gandhi's influence on King

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Nelson Mandela, The Sacred Warrior: The liberator of South Africa looks at the seminal work of the liberator of India, Time Magazine, 3 January 2000.

- ↑ A pacifist uncovered — Abdul Ghaffar Khan, Pakistani pacifist

- ↑ An alternative Gandhi

- ↑ Einstein on Gandhi

- ↑ Lennon Lives Forever. Taken from rollingstone.com. Retrieved on 20 May 2007.

- ↑ Of Gandhigiri and Green Lion, Al Gore wins hearts at Cannes. Taken from exchange4media.com. Retrieved on 23 June 2007.

- ↑ Chaudhury, Nilova (15 June 2007). "2 October is global non-violence day", hindustantimes.com, Hindustan Times. Retrieved on 2007-06-15.

- ↑ Dutta, Krishna and Andrew Robinson, Rabindranath Tagore: An Anthology, p. 2.

- ↑ "Kamdartree: Mahatma and Kamdars".

- ↑ M.K. Gandhi: An Autobiography. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ↑ Documentation of how and when Mohandas K. Gandhi became known as the "Mahatma". Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ↑ The Children Of Gandhi. Time (magazine). Retrieved on 21 April 2007.

- ↑ AFSC's Past Nobel Nominations.

- ↑ Amit Baruah. "Gandhi not getting the Nobel was the biggest omission". The Hindu, 2006. Retrieved 17 October 2006.

- ↑ Øyvind Tønnesson. Mahatma Gandhi, the Missing Laureate. Nobel e-Museum Peace Editor, 1998–2000. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ↑ reprinted in The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas., Louis Fischer, ed., 2002 (reprint edition) pp. 106–108.

- ↑ reprinted in The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas.Louis Fischer, ed., 2002 (reprint edition) pp. 308–9.

- ↑ Jack, Homer. The Gandhi Reader, p. 418.

- ↑ "The life and death of Mahatma Gandhi", on BBC News, see section "Independence and partition."

- ↑ reprinted in The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas., Louis Fischer, ed., 2002 (reprint edition) pp. 286-288.

- ↑ SANET-MG Archives - September 2001 (#303)

- ↑ Mahatama Gandhi on Bhagat Singh.

- ↑ Gandhi — 'Mahatma' or Flawed Genius?.

- ↑ reprinted in The Essential Gandhi: An Anthology of His Writings on His Life, Work, and Ideas., Louis Fischer, ed., 2002 (reprint edition) p. 311.

- ↑ Jack, Homer. The Gandhi Reader, pp. 319–20.

- ↑ 83.0 83.1 Jack, Homer. The Gandhi Reader, p. 322.

- ↑ Jack, Homer. The Gandhi Reader, pp. 323–4.

- ↑ Jack, Homer The Gandhi Reader, pp. 324–6.

- ↑ David Lewis Schaefer. What Did Gandhi Do?. National Review, 28 April 2003. Retrieved 21 March 2006; Richard Grenier. "The Gandhi Nobody Knows". Commentary Magazine. March 1983. Retrieved 21 March 2006.

- ↑ Hertzberg, Arthur. The Zionist Idea. PA: Jewish Publications Society, 1997, pp. 463-464.; see also Gordon, Haim. "A Rejection of Spiritual Imperialism: Reflections on Buber's Letter to Gandhi." Journal of Ecumenical Studies, 22 June 1999.

- ↑ Jack, Homer. The Gandhi Reader, Harijan, 26 November 1938, pp. 317–318.

- ↑ Mohandas K. Gandhi. A Non-Violent Look at Conflict & Violence Published in Harijan on 26 November 1938

- ↑ The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. 8. pp. 199.

- ↑ The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. 3. pp. 255.

- ↑ The Collected Works of Mahatma Gandhi. 2. pp. 270.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 Rory Carroll, "Gandhi branded racist as Johannesburg honours freedom fighter", The Guardian, 17 October 2003.

- ↑ The Making of a Political Reformer: Gandhi in South Africa, 1893–1914

- ↑ The Making of a Political Reformer: Gandhi in South Africa, 1893–1914. Surendra Bhana and Goolam Vahed, 2005: p.44