Mobile, Alabama

| City of Mobile | |||

|

|||

|

|||

| Nickname(s): The Port City or Azalea City or The City of Six Flags | |||

|

|||

| Coordinates: | |||

| Country | United States | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| State | Alabama | ||

| County | Mobile | ||

| Founded | 1702 | ||

| Incorporated | 1814 | ||

| Government | |||

| - Mayor | Sam Jones | ||

| Area | |||

| - City | 159.4 sq mi (412.9 km²) | ||

| - Land | 117.9 sq mi (305.3 km²) | ||

| - Water | 41.5 sq mi (107.6 km²) | ||

| Elevation (lowest)[1] | 10 ft (3 m) | ||

| Population (2000)[2][3] | |||

| - City | 198,915 | ||

| - Metro | 399,843 | ||

| Time zone | CST (UTC-6) | ||

| - Summer (DST) | CDT (UTC-5) | ||

| ZIP Codes | 36601-36613, 36615-36619, 36621-36622, 36625, 36628, 36630, 36633, 36640-36641, 36644, 33652, 36660, 36663, 36670-36671, 36675, 36685, 36688-36691, 36693, 36695 | ||

| Area code(s) | 251 | ||

| FIPS code | 01-50000 | ||

| GNIS feature ID | 0155153 | ||

| Website: http://www.cityofmobile.org | |||

Mobile (IPA: /moʊˈbiːl/) is the third most populous city in the Southern U.S. state of Alabama and is the county seat of Mobile County.[4] It is located on the central Gulf Coast of the United States. The population within the city limits was 198,915 during the 2000 census.[2] Mobile is the principal municipality of the Mobile Metropolitan Statistical Area, a region of 399,843 residents which is composed solely of Mobile County and is the second largest MSA in the state.[3] Mobile is included in the Mobile-Daphne-Fairhope Combined Statistical Area with a total population of 540,258, the second largest CSA in the state.[5]

Mobile began as the first capital of colonial French Louisiana in 1702, and during its first 100 years, Mobile was a colony for France, then Britain, and lastly Spain. The city gained its name from the Native American Mobilian tribe that the French colonists found in the area of Mobile Bay.[6] Mobile first became a part of the United States of America in 1813, left the United States with Alabama in 1861 to become a part of the Confederate States of America, and then returned to the United States in 1865.[7]

Located at the junction of the Mobile River and Mobile Bay on the northern Gulf of Mexico, the city is the only seaport in Alabama.[8] The Port of Mobile has always played a key role in the economic health of the city beginning with the city as a key trading center between the French and Native Americans[9] down to its current role as the 10th largest port in the United States.[10]

As one of the Gulf Coast's cultural centers, Mobile houses several art museums, a symphony orchestra, a professional opera, a professional ballet company, and a large concentration of historic architecture.[11][12] Mobile is known for having the oldest organized Carnival celebrations in the United States, dating to its early colonial period. It was also host to the first formally organized Carnival mystic society or krewe in the United States, dating to 1830.[13] People from Mobile are known as Mobilians.[9]

Contents |

History

- See also: History of Mobile, Alabama

Colonial

The settlement of Mobile, then known as Fort Louis de la Louisiane, was first established in 1702, at Twenty-seven Mile Bluff on the Mobile River, as the first capital of the French colony of Louisiana. It was founded by French Canadian brothers Pierre Le Moyne d'Iberville and Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville, in order to establish control over France's Louisiana claims with Bienville having been made governor of French Louisiana in 1701. Mobile’s Roman Catholic parish was established on 20 July 1703, by Jean-Baptiste de la Croix de Chevrières de Saint-Vallier, Bishop of Quebec.[14] The parish was the first established on the Gulf Coast of the United States.[14] The year 1704 saw the arrival of 23 women to the colony aboard the Pélican, along with yellow fever introduced to the ship in Havana.[15] Though most of the "Pélican girls" recovered, a large number of the existing colonists and the neighboring Native Americans died from the illness.[15] This early period also saw the arrival of the first African slaves aboard a French supply ship from Saint-Domingue.[15] The population of the colony fluctuated over the next few years, growing to 279 persons by 1708 yet descending to 178 persons two years later due to disease.[14]

These additional outbreaks of disease and a series of floods caused Bienville to order the town relocated several miles downriver to its present location at the confluence of the Mobile River and Mobile Bay in 1711.[16] A new earth and palisade Fort Louis was constructed at the new site during this time.[17] By 1712, when Antoine Crozat took over administration of the colony by royal appointment, the colony boasted a population of 400 persons. The capital of Louisiana was moved to Biloxi in 1720,[17] leaving Mobile in the role of military and trading center. In 1723 the construction of a new brick fort with a stone foundation began[17] and it was renamed Fort Condé in honor of Louis Henri, Duc de Bourbon and prince of Condé.[18]

In 1763, the Treaty of Paris was signed, ending the French and Indian War. The treaty ceded Mobile and the surrounding territory to the Kingdom of Great Britain, and it was made a part of the expanded British West Florida colony.[19] The British changed the name of Fort Condé to Fort Charlotte, after Charlotte of Mecklenburg-Strelitz, King George III's queen.[20] The British were eager not to lose any useful inhabitants and promised religious tolerance to the French colonists, ultimately 112 French Mobilians remained in the colony.[21] In 1766 the population was estimated to be 860, though the town's borders were smaller than they had been during the French colonial efforts.[21] During the American Revolutionary War, West Florida and Mobile became a refuge for loyalists fleeing the other colonies.[22]

The Spanish captured Mobile during the Battle of Fort Charlotte in 1780. They wished to eliminate any British threat to their Louisiana colony, which they had received from France in 1763s Treaty of Paris.[22] Their actions were also condoned by the revolting American colonies due to the fact that West Florida, for the most part, remained loyal to the British Crown.[22] The fort was renamed Fortaleza Carlota, with the Spanish holding Mobile as a part of Spanish West Florida until 1813, when it was seized by the U.S. General James Wilkinson during the War of 1812.[23]

19th century

When Mobile was made a part of the Mississippi Territory in 1813, the population had dwindled to roughly 300 people.[24] The city was included in the Alabama Territory in 1817, after Mississippi gained statehood. Alabama was granted statehood in 1819 and Mobile's population had increased to 809 by that time.[24] As the inland areas of Alabama and Mississippi were settled by farmers and the plantation economy became established, Mobile's population exploded. It came to be settled by merchants, attorneys, mechanics, doctors and others seeking to capitalize on trade with these upriver areas.[24] With its location at the mouth of the Mobile River, a river system that served as the principal navigational access for most of Alabama and a large part of Mississippi, Mobile was well situated for this purpose. By 1822 the population was 2800.[24]

From the 1830s onward Mobile expanded into a city of commerce with a primary focus on the cotton trade.[24] The waterfront was developed with wharves, terminal facilities, and fire-proof brick warehouses.[24] The exports of cotton grew in proportion to the amounts being produced in the Black Belt and by 1840 Mobile was second only to New Orleans in cotton exports in the nation.[24] With the economy so focused on this one crop, Mobile's fortunes were always tied to those of cotton and the city weathered many financial crises during this period.[24] Though Mobile had a relatively small slave owning population itself compared to the inland areas, it was the slave-trading center of the state until surpassed by Montgomery in the 1850s.[25] By 1860 Mobile's population within the city limits had reached 29,258 people, it was the 27th largest city in the United States and 4th largest in what would soon be the Confederate States of America.[26] The population in the whole of Mobile County, including the city, consisted of 29,754 free citizens, of which 1195 were African American.[27] Additionally, there were 1785 slave owners, holding 11,376 slaves, for a total county population of 41,130 people.[27]

During the American Civil War, Mobile was a Confederate city. The first submarine to successfully sink an enemy ship, the H. L. Hunley, was built in Mobile.[28] One of the most famous naval engagements of the war was the Battle of Mobile Bay, resulting in the Union taking possession of Mobile Bay on 5 August 1864.[29] On 12 April 1865, 3 days after the surrender of Robert E. Lee at Appomattox Courthouse, the city of Mobile surrendered to the Union army to avoid destruction following the Union victories at the Battle of Spanish Fort and the Battle of Fort Blakely.[29] Ironically, on 25 May 1865, the city suffered loss when some three hundred people died as a result of an explosion at a federal ammunition depot on Beauregard Street. The explosion left a 30-foot (9 m) deep hole at the depot's location, sunk ships docked on the Mobile River, and the resulting fires destroyed the northern portion of the city.[30]

Federal Reconstruction in Mobile began after the Civil War and effectively ended in 1874 when the local Democrats gained control of the city government.[31] The last quarter of the 19th century was a time of economic depression and municipal insolvency for Mobile. One example can be provided by the value of Mobile's exports during this period of depression. The value of exports leaving the city fell from $9 million in 1878 to $3 million in 1882.[32]

20th century

The turn of the century brought the Progressive Era to Mobile and saw Mobile's economic structure evolve along with a significant increase in population.[33] The population increased from around 40,000 in 1900 to 60,000 by 1920.[33] During this time the city received $3 million in federal grants for harbor improvements, which drastically deepened the shipping channels in the harbor.[33] During and after World War I manufacturing became increasingly vital to Mobile's economic health with shipbuilding and steel production being two of the most important.[33] During this time social equality and race relations in Mobile worsened, however.[33] In 1902 the city government passed Mobile's first segregation ordinance, one that segregated the city streetcars.[33] Mobile's African American population responded to this with a two-month boycott which was ultimately unsuccessful.[33] After this, Mobile's de facto segregation would increasingly be replaced with legislated segregation.[33]

World War II led to a massive military effort causing a considerable increase in Mobile's population, largely due to the huge influx of workers coming into Mobile to work in the shipyards and at the Brookley Army Air Field.[34] Between 1940 and 1943, more than 89,000 people moved into Mobile to work for war effort industries.[34] Mobile was one of eighteen U.S. cities producing Liberty ships at its Alabama Drydock and Shipbuilding Company to support the war effort by producing ships faster than the Axis powers could sink them.[34] Gulf Shipbuilding Corporation, a subsidiary of Waterman Steamship Corporation, focused on building freighters, Fletcher class destroyers, and minesweepers.[34]

The years after World War II brought about changes in Mobile's social structure and economy. Instead of shipbuilding being a primary economic force, the paper and chemical industries began to take over and most of the old military bases were converted to civilian uses. This period saw the end of racial segregation with the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Though many in Mobile had considered the city to be tolerant and racially accommodating compared to other cities in the South, with the police force and one local college becoming integrated in the 1950s and the voluntary desegregation of buses and lunch counters by the early 1960s, Mobile's African American citizens were not nearly as content with the status quo as some believed. In 1963 three African American students brought a case against the Mobile County School Board for being denied admission to Murphy High School.[35] The court ordered that the three students be admitted to Murphy for the 1964 school year, leading to the desegregation of Mobile County's school system.[35]

Mobile's economy took a large hit in late 1960s with the closing of Brookley Air Force Base. This and other factors ushered in a period of economic depression that lasted through the 1970s. Beginning in the late 1980s, the city council and mayor began an effort termed the "String of Pearls Initiative" to make Mobile into a competitive, urban city.[36] This effort would see the building of numerous new facilities and projects around the city and the restoration of hundreds of other historic downtown buildings and homes.[36] This period also saw a reduction in the rate of violent crime and a concerted effort by city and county leaders to attract new business ventures to the area.[37] The effort continues into the present with new city government leadership.[37] Shipbuilding began to make a major comeback in Mobile with the founding in 1999 of Austal USA, a joint venture of Australian shipbuilder, Austal, and Bender Shipbuilding.[38]

Geography and climate

Geography

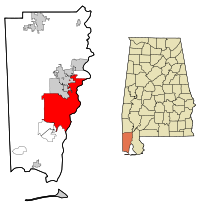

Mobile is located at 30°40'46" North, 88°6'12" West (30.679523, -88.103280)[39], in the southwestern corner of the U.S. state of Alabama. According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 412.9 km² (159.4 mi²). 305.4 km² (117.9 mi²) of it is land and 107.6 km² (41.5 mi²) of it is water.[40] The elevation in Mobile ranges from 10 ft (3 m) on Water Street in downtown[1] to 211 ft (64 m) at the Mobile Regional Airport.[41]

Climate

Mobile's geographical location on the Gulf of Mexico provides a mild subtropical climate, with an average annual temperature of 67.5 °F (20 °C). Normal average January through December temperatures range from 40 °F (4 °C) minimum and 91 °F (33 °C) maximum.[42] Mobile has hot, humid summers and mild, rainy winters. A 2007 study by WeatherBill, Inc. determined that Mobile is the wettest city in the contiguous 48 states, with 67 inches (170 cm) of average annual rainfall.[43] Mobile averages 59 rainy days per year.[43] Snow is rare in Mobile, with the last snowfall being on 18 December 1996.[44]

Being on the Gulf, Mobile is occasionally affected by major tropical storms and hurricanes.[45] Mobile suffered a major natural disaster on the night of 12 September 1979 when Category 3 Hurricane Frederic passed over the heart of the city. The storm caused tremendous damage to Mobile and the surrounding area.[46] Mobile received moderate damage from Hurricane Opal on 4 October 1995 and Hurricane Ivan on 16 September 2004.[47] Mobile also received moderate damage from Hurricane Katrina on 29 August 2005. A storm surge of 11.45 feet (3.49 m) damaged eastern sections of Mobile and caused extensive flooding in downtown.[48]

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Average high °F (°C) | 61 (16) |

65 (18) |

71 (22) |

77 (25) |

84 (29) |

89 (32) |

91 (33) |

91 (33) |

87 (31) |

79 (26) |

70 (21) |

63 (17) |

|

| Average low °F (°C) | 40 (4) |

42 (6) |

49 (9) |

55 (13) |

63 (17) |

69 (21) |

72 (22) |

72 (22) |

68 (20) |

56 (13) |

48 (9) |

42 (6) |

|

| Precipitation inches (mm) | 6 (152.4) |

5 (127) |

7 (177.8) |

5 (127) |

6 (152.4) |

5 (127) |

6 (152.4) |

6 (152.4) |

6 (152.4) |

3 (76.2) |

5 (127) |

5 (127) |

|

| Source: US Travel Weather[49] 2007-12-03 | |||||||||||||

Culture

Mobile is home to an array of cultural influences with its French, British, Spanish, African, Creole and Catholic heritage distinguishing it from all other cities in the state of Alabama. The annual Carnival celebration is perhaps the best illustration of this. Carnival in Mobile has evolved over the course of 300 years from a sedate French Catholic tradition into a mainstream multi-week celebration across the spectrum of cultures.[50]

Carnival and Mardi Gras

- See also: Mardi Gras in Mobile

- See also: Mystic society

Mobile's Carnival celebrations start as early as November with several balls,[51] with the parades usually beginning after January 5.[52] Carnival celebrations end promptly at the stroke of midnight on Mardi Gras, signaling the beginning of Ash Wednesday and the first day of Lent.[53] Mardi Gras, though literally meaning Fat Tuesday and thus the last day of the Carnival season, is normally used locally to refer to the entire Carnival season. During this time Mobile's mystic societies build colorful Carnival floats and parade throughout downtown with masked society members tossing small gifts, known as throws, to the parade spectators.[54] Mobile's mystic societies also give formal masquerade balls, which are almost always invitation only and are oriented to adults.[52]

Mobile first celebrated Carnival in 1703 when French settlers began the festivities at the Old Mobile Site.[13] Mobile's first Carnival society began in 1711 with the Boeuf Gras Society (Fatted Ox Society).[55] Mobile's Cowbellion de Rakin Society was the first formally organized and masked mystic society in the United States to celebrate with a parade in 1830.[13][53] The Cowbellions got their start when a cotton factor from Pennsylvania, Michael Krafft, began a parade with rakes, hoes, and cowbells.[53] The Cowbellians introduced horse-drawn floats to the parades in 1840 with a parade entitled, “Heathen Gods and Goddesses.[55] The Striker's Independent Society was formed in 1843 and is the oldest remaining mystic society in the United States.[55] Carnival celebrations in Mobile were canceled during the American Civil War. Mardi Gras parades were revived by Joe Cain in 1866 when he paraded through the city streets on Fat Tuesday while costumed as a fictional Chickasaw chief named Slacabamorinico, irreverently celebrating the day in front of the occupying Union Army troops.[56] The year 2002 saw Mobile's Tricentennial celebrated with parades that represented all of Mobile's mystic societies.[55]

Archives and libraries

The National African American Archives and Museum features the history of "Colored Carnival", African American participation in Mobile's Mardi Gras, authentic artifacts from the era of slavery, and portraits and biographies of famous African Americans.[57] The University of South Alabama Archives houses primary source material relating to the history of Mobile and southern Alabama as well as the university's history. The archives are located on the ground floor of the USA Spring Hill Campus and are open to the general public.[58] The Mobile Municipal Archives contains the extant records of the City of Mobile, dating from the city's creation as a municipality by the Mississippi Territory in 1814. The majority of the original records of Mobile's colonial history (1702-1813) are housed in Paris, London, Seville, and Madrid.[59] The Mobile Genealogical Society Library and Media Center is located at the Holy Family Catholic Church and School complex and features written and published materials for use in genealogical research.[60] The Mobile Public Library system serves Mobile and consists of eight branches across Mobile County, featuring its own large local history and genealogy division housed in a facility next to the newly restored and enlarged Ben May Main Library on Government Street.[61] The Saint Ignatius Archives, Museum and Theological Research Library contains primary sources, artifacts, documents, photographs and publications that pertain to the history of Saint Ignatius Church and School, the Catholic history of the city, and the history of the Roman Catholic Church.[62]

Entertainment and arts

The Mobile Museum of Art features European, Non-Western, American, and Decorative Arts collections.[11] The Saenger Theatre of Mobile was opened in 1927 and is a modern dynamic performing arts center. It is home to the Mobile Symphony and Space 301, a contemporary art gallery. It also serves as a small concert venue for the city.[63] The Mobile Civic Center contains three facilities under one roof. The 400,000 sq ft (37,161 m2) building has an arena, a theater and an exposition hall. It is the primary concert venue for the city and hosts a wide variety of events. It is home to the Mobile Opera and the Mobile Ballet.[12] The 60-year old Mobile Opera averages about 1,200 attendees per performance.[64] A wide variety of events are held at Mobile's Arthur C. Outlaw Convention Center. It contains a 100,000 sq ft (9,290 m2) exhibit hall, a 15,000 sq ft (1,394 m2) grand ballroom, and sixteen meeting rooms.[65] Additionally, the city is host to BayFest, an annual three day music festival with over 125 live musical acts on nine stages.[66]

Tourism

Museums

Mobile is home to a variety of museums. Battleship Memorial Park is a military park on the shore of Mobile Bay and features the World War II era battleship USS Alabama (BB-60), the World War II era submarine USS Drum (SS-228), Korean War and Vietnam War Memorials, and a variety of historical military equipment.[67] The Museum of Mobile chronicles 300 years of Mobile history and material culture and is housed in the historic Old City Hall (1857).[68] The Oakleigh Historic Complex features three house museums that interpret the lives of people from three levels of Mobile society in the mid-19th century.[69] The Mobile Carnival Museum, which houses the city's Mardi Gras history and memorabilia, documents the variety of floats, costumes, and displays seen during the history of the festival season.[70] The Bragg-Mitchell Mansion (1855),[71] Richards DAR House (1860),[72] and the Conde-Charlotte House (1822)[73] are historic antebellum house museums. Fort Morgan, Fort Gaines, and Historic Blakeley State Park figure into local American Civil War history. The Mobile Medical Museum is housed in the historic Vincent-Doan House (1827) and features artifacts and resources that chronicle the history of medicine in Mobile.[74] The Phoenix Fire Museum is located in the restored Phoenix Volunteer Fire Company Number 6 building and features the history of fire companies in Mobile from their organization in 1838.[75] The Mobile Police Department Museum features exhibits that chronicle the history of law enforcement in Mobile.[76] The Gulf Coast Exploreum is a non-profit science center located in downtown. It features permanent and traveling exhibits, an IMAX dome theater, a digital 3D virtual theater, and a hands-on chemistry laboratory.[77] The Dauphin Island Sea Lab is located south of the city near the mouth of Mobile Bay. It houses the Estuarium, an aquarium which illustrates the four habitats of the Mobile Bay ecosystem: the river delta, bay, barrier islands and Gulf of Mexico.[78]

Parks and other attractions

The Mobile Botanical Gardens feature a variety of flora spread over 100 acres (40 ha). It contains the Millie McConnell Rhododendron Garden with 1,000 evergreen and native azaleas and the 30-acre (12 ha) Longleaf Pine Habitat.[79] The Bellingrath Gardens and Home are located on Fowl River and contain 65 acres (26 ha) of landscaped gardens and a 10,500 sq ft (975 m2) mansion dating to the 1930s.[80] The 5 Rivers Delta Resource Center is a new facility for exploring the Mobile, Spanish, Tensaw, Appalachee, and Blakeley River delta.[81]

Mobile has more than 45 public parks with some that are of special interest.[82] Bienville Square is a historic park dating to 1850 in the Lower Dauphin Street Historic District and is named for Mobile’s founder, Jean-Baptiste Le Moyne, Sieur de Bienville.[83] This park was once a principle gathering place for the citizens of the city and remains popular today. Cathedral Square is a performing arts park in the Lower Dauphin Street Historic District overlooked by the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception.[84] Fort Condé is a reconstruction of the original Fort Condé, built on the old fort's footprint. It is the city’s official welcome center and living history museum.[17] Spanish Plaza is a downtown park that honors the Spanish occupation of the city between 1780 and 1813. It features the "Arches of Friendship", a fountain presented to Mobile by the city of Málaga, Spain.[85] Langan Park is a 720-acre (291 ha) municipal park that features lakes and natural spaces.[82] It is home to the Mobile Museum of Art, Azalea City Golf Course, Mobile Botanical Gardens and Playhouse in the Park.[82]

Historic architecture

Mobile has antebellum architectural examples of Greek Revival, Gothic Revival, Italianate, and Creole cottage. Later architectural styles found in the city include the various Victorian types, shotgun types, Colonial Revival, Tudor Revival, Spanish Colonial Revival, Beaux-Arts and many others. The city currently has nine major historic districts consisting of Old Dauphin Way, Oakleigh Garden, Lower Dauphin Street, Leinkauf, De Tonti Square, Church Street East, Ashland Place, Campground, and Midtown.[86]

Mobile has a number of historic structures spread throughout the city. Some of Mobile's historic churches include Christ Church Cathedral, the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception, Government Street Presbyterian Church, and Trinity Episcopal Church. Two historic Roman Catholic convents survive, the Convent and Academy of the Visitation and the Convent of Mercy. The Stone Street Baptist Church is a historic African American church that was established in the 1840s. Barton Academy is a historic Greek Revival school building and local landmark on Government Street. The Bishop Portier House and the Carlen House are two of the many surviving examples of Creole cottages in the city. The Mobile City Hospital and the United States Marine Hospital are both restored Greek Revival hospital buildings that predate the Civil War. The Washington Firehouse No. 5 is a Greek Revival fire station, built in 1851. The Hunter House is an example of the Italianate style and was built by a successful 19th century African American businesswoman. The Shepard House is a good example of the Queen Anne style. The Scottish Rite Temple is the only surviving example of Egyptian Revival architecture in the city. The Gulf, Mobile, and Ohio Passenger Terminal is an example of the Mission Revival style.

The city has several historic cemeteries that were established after the colonial era. They replaced Mobile's colonial Campo Santo, of which no traces remain. The Church Street Graveyard contains above-ground tombs and monuments spread over 4 acres (2 ha) and was founded in 1819, during the height of the yellow fever epidemics.[87] The nearby 120-acre (49 ha) Magnolia Cemetery was established in 1836 and was Mobile's primary burial site during the 19th century with approximately 80,000 burials.[88] It features tombs and many intricately carved monuments and statues.[89][90] The Old Catholic Cemetery was established in 1848 by the Archdiocese of Mobile and covers more than 150 acres (61 ha). It contains plots for the Brothers of the Sacred Heart, Little Sisters of the Poor, Sisters of Charity, and Sisters of Mercy, in addition to many other historically significant burials.[91] Mobile's Jewish community dates back to the 1820s and the city has two historic Jewish cemeteries, Ahavas Chesed Cemetery and Sha'arai Shomayim Cemetery.[92]

Demographics

| Historical populations | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1830 | 3,194 |

|

|

| 1840 | 12,672 | 296.7% | |

| 1850 | 20,515 | 61.9% | |

| 1860 | 29,258 | 42.6% | |

| 1870 | 32,034 | 9.5% | |

| 1880 | 29,132 | −9.1% | |

| 1890 | 31,076 | 6.7% | |

| 1900 | 38,469 | 23.8% | |

| 1910 | 51,521 | 33.9% | |

| 1920 | 60,777 | 18% | |

| 1930 | 68,202 | 12.2% | |

| 1940 | 78,720 | 15.4% | |

| 1950 | 129,009 | 63.9% | |

| 1960 | 202,779 | 57.2% | |

| 1970 | 190,026 | −6.3% | |

| 1980 | 200,452 | 5.5% | |

| 1990 | 196,278 | −2.1% | |

| 2000 | 198,915 | 1.3% | |

| Est. 2006 | 194,822 | −2.1% | |

The 2000 census determined that there were 198,915 people residing within the city limits.[2] Mobile is the center of Alabama's second-largest metropolitan area, which consists of all of Mobile County. Metropolitan Mobile (MSA) had a population of 399,843 as of 2000 census.[3]

There were 73,057 households out of which 22,225 had children under the age of 18 living with them, 29,963 were married couples living together, 15,360 had a female householder with no husband present, 3,488 had a male householder with no wife present, and 24,246 were non-families.[93] 20,957 of all households were made up of individuals and 7,994 had someone living alone who is 65 years of age or older.[93] The racial makeup of the city was 48.2% White, 47.9% Black or African American, 0.2% Native American, 1.8% Asian, 0.3% Pacific Islander, 0.5% from other races, 0.9% from two or more races, and 1.2% of the population were Latino.[93] The average household size was 2.59 and the average family size was 3.23.[93]

The population was spread out with 7.1% under the age of 5, 73.6% over 18, and 13.4% over 65.[93] The median age was 35.6 years.[93] The male population was 47.6% and the female population was 52.4%.[93] The median income for a household in the city was $37,439, and the median income for a family was $45,217.[93] The per capita income for the city was $21,612. 21.3% of the population and 17.6% of families were below the poverty line.[93]

Government

City

- See also: List of mayors of Mobile, Alabama

Since 1985 the government of Mobile has consisted of a mayor and a seven member city council.[94] The mayor is elected at-large and the council members are elected from each of the seven city council districts. A supermajority of five votes is required to conduct council business. This form of city government was chosen by the voters after the previous form of government, which used three city commissioners who were elected at-large, was ruled to substantially dilute the African American vote in the 1975 case Bolden v. City of Mobile.[95] Municipal elections are held every four years.

The current mayor, Sam Jones, was elected in September 2005 and is the first African American mayor of Mobile.[96] As of January 2006, the city council is composed of Fredrick Richardson, Jr. from District 1, William Carroll from District 2, Clinton Johnson from District 3, John C. Williams from District 4, Reggie Copeland, Sr. from District 5, Connie Hudson from District 6, and Gina Gregory from District 7. Reggie Copeland, Sr. is currently serving as Council President with Fredrick Richardson, Jr. serving as Council Vice President.[97]

In January 2008, the city hired EDSA, an urban design firm, to create a new comprehensive master plan for the downtown area and surrounding neighborhoods. The planning area is bordered on the east by the Mobile River, to the south by Interstate 10 and Duval Street, to the west by Houston Street and to the north by Three Mile Creek and the neighborhoods north of Martin Luther King Avenue.[98]

State

Mobile is represented in the Alabama Legislature by three senators and nine representatives. Mobile is represented in the Alabama Senate by Democrat Vivian Davis Figures from the 33rd district, by Republican Rusty Glover from the 34th district, and by Republican Ben Brooks from the 35th district.[99] Mobile is represented in the Alabama House of Representatives by Democrat Yvonne Kennedy from the 97th district, Democrat James O. Gordon from the 98th district, Democrat James Buskey from the 99th district, Republican Victor Gaston from the 100th district, Republican Jamie Ison from the 101st district, Republican Chad Fincher from the 102nd district, Democrat Joseph C. Mitchell from the 103rd district, Republican Jim Barton from the 104th district, and Republican Spencer Collier from the 105th district.[100]

Education

Primary and secondary

Public facilities

- See also: Mobile County Public School System

Public schools in Mobile are operated by the Mobile County Public School System. The Mobile County Public School System has an enrollment of over 65,000 students, employs approximately 8,500 public school employees, and had a budget in 2005-2006 of $617,162,616.[101] The State of Alabama operates the Alabama School of Mathematics and Science on Dauphin Street in Mobile, which boards advanced Alabama high school students. It was founded in 1989 to identify, challenge, and educate future leaders.[102]

Private facilities

Mobile also has a large number of private schools, most of them being parochial in nature. Many of these belong to the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Mobile. The private Catholic institutions include McGill-Toolen Catholic High School (1896), Corpus Christi School, Little Flower Catholic School (1934), Most Pure Heart of Mary Catholic School (1900), Saint Dominic School (1961), Saint Ignatius School (1952), Saint Mary Catholic School (1867), Saint Pius X Catholic School (1957), and Saint Vincent DePaul Catholic School (1976).[103] The private Protestant institutions include St. Paul's Episcopal School (1947), Mobile Christian School (1961), St. Lukes Episcopal School (1961), Faith Academy (1967), and the Cottage Hill Baptist School System (1970), which operates Cottage Hill Baptist School and Cottage Hill Christian Academy.[103] UMS-Wright Preparatory School (1893) is an independent, non-religious, co-educational preparatory school.[103]

Tertiary

Colleges and universities in Mobile include the University of South Alabama, Spring Hill College, the University of Mobile, Faulkner University, and Bishop State Community College.[104]

The University of South Alabama is a public, doctoral-level university established in 1963. The university is composed of the College of Arts and Sciences, the Mitchell College of Business, the College of Education, the College of Engineering, the College of Medicine, the Doctor of Pharmacy Program, the College of Nursing, the School of Computer and Information Sciences, and the School of Continuing Education and Special Programs.[105]

Spring Hill College, chartered in 1830, was the first Catholic college in the southeastern U.S. and is the third oldest Jesuit college in the country.[106] This four-year private college offers graduate programs in Business Administration, Education, Liberal Arts, Nursing (MSN), and Theological Studies.[107] Undergraduate divisions and programs include the Division of Business, the Communications/Arts Division, International Studies, Interdivisional Studies, the Language and Literature Division, Nursing (BSN), Philosophy and Theology, Political Science, the Sciences Division, the Social Sciences Division, and the Teacher Education Division.[108]

The University of Mobile is a four-year private Baptist-affiliated university that was founded in 1961. It consists of the College of Arts and Sciences, School of Business, School of Christian Studies, School of Education, the School of Leadership Development, and the School of Nursing.[109]

Faulkner University is a four-year private Church of Christ-affiliated university based in Montgomery, Alabama. The Mobile campus was established in 1975 and offers bachelor's degrees in Business Administration, Management of Human Resources, and Criminal Justice.[110] It also offers associate degrees in Business Administration, Business Information Systems, Computer & Information Science, Criminal Justice, Informatics, Legal Studies, Arts, and Science.[111]

Bishop State Community College, founded in 1927, is a two-year public institution with four campuses in Mobile and offers a wide array of associate degrees.[112]

Healthcare

Mobile serves the central Gulf Coast as a regional center for medicine. The city is served by over 850 physicians and 175 dentists. There are four major medical centers within the city limits: Mobile Infirmary Medical Center with 704 beds, Springhill Medical Center with 252 beds, Providence Hospital with 349 beds, and the University of South Alabama Medical Center with 346 beds and a level I trauma center.[113] Additionally, the University of South Alabama also operates USA Children's & Women's Hospital with 219 beds, dedicated exclusively to the care of children and women, and Mobile Infirmary Medical Center operates Infirmary West with 100 acute care beds.[113] BayPointe Hospital and Children’s Residential Services is a 94-bed psychiatric hospital that houses a residential unit for children, an acute unit for children and adolescents, and an involuntary hospital unit for adults undergoing evaluation ordered by the Mobile Probate Court.[114] The city has a broad array of outpatient surgical centers, emergency clinics, home health care services, assisted-living facilities and skilled nursing facilities.[115][113]

Economy

Aerospace, retail, services, construction, medicine, and manufacturing are Mobile's major industries. After experiencing economic decline for several decades, Mobile's economy began to rebound in the late 1980s. Between 1993 and 2003 13,983 new jobs were created as 87 new companies were founded and 399 existing companies were expanded. 1,700 new jobs were created from February 2003 to February 2004.[116] According to the U.S. Department of Labor's Bureau of Labor Statistics, Mobile's unemployment rate is 4.2% as of May 2008.[117]

Expansion

Mobile's Alabama State Docks is currently undergoing the largest expansion in its history by expanding its container processing and storage facility and increasing container storage at the docks by over 1,000%.[118] As of 2006, the Port of Mobile was the 10th largest by tonnage in the United States.[10]

In 2005 Austal USA, based in Mobile, expanded their production facility for US defense and commercial aluminium shipbuilding.[119] In 2007 German steel manufacturer ThyssenKrupp announced plans for a $3.7 billion steel mill.[120] The new plant is currently under construction in northern Mobile County. Company officials state that 2,700 permanent jobs will be added to the local economy.[120]

On 29 February 2008, the United States Air Force announced that a partnership between Northrop Grumman and EADS had won the contract to produce the new KC-45 aerial refueling tanker. The contract is considered to be worth up to $40 billion with 179 planes to be delivered over the next ten to fifteen years. The production of these aircraft will be at Mobile's Brookley Complex.[121][122][123]

Brookley Complex

The Brookley Complex, also known as the Mobile Downtown Airport, is an industrial complex and airport located 3 miles (5 km) south of the central business district of the city. It is currently the largest industrial and transportation complex in the region with over 100 companies, many of which are aerospace, and 4000 employees on 1,700 acres (688 ha).[124] Brookley includes the largest private employer in Mobile County, Mobile Aerospace Engineering, a subsidiary of Singapore Technologies Engineering.[124]

Transportation

Air

Local airline passengers are served by the Mobile Regional Airport which directly connects to five major hub airports: Charlotte, Dallas, Atlanta, Houston, and Memphis.[125] It is served by American Airlines, Continental Express, Delta Air Lines, Northwest Airlink and US Airways Express.[125] The Brookley Complex serves corporate, cargo and private cargo aircraft.[125]

Rail

Mobile is served by seven railroads. Five of these are Class I railroads and include the Burlington Northern Santa Fe (BNSF), Canadian National Railway (CNR), CSX Transportation (CSX), the Kansas City Southern Railway (KCS), and the Norfolk Southern Railway (NS). All five of these converge at the Port of Mobile, which provides intermodal freight transport service to companies engaged in importing and exporting.[126] Mobile is also served by a switching railroad, the Terminal Railway of Alabama State Docks (TASD). The seventh railroad is the Central Gulf Railroad, which is a rail ship service to Coatzacoalcos, Veracruz in Mexico.[126] The city was served by Amtrak's Sunset Limited passenger train service until 2005, when the service was suspended due to the effects of Hurricane Katrina.[127][128]

Road

Two major interstate highways and a spur converge in Mobile. Interstate 10 runs northeast to southwest across the city while Interstate 65 starts in Mobile at Interstate 10 and runs north. Interstate 165 connects to Interstate 65 north of the city in Prichard and joins Interstate 10 in downtown Mobile.[129] Mobile is well served by many major highway systems. United States Highways US 31, US 43, US 45, US 90 and US 98 radiate from Mobile traveling east, west, and north. Mobile has three routes east across the Mobile River and Mobile Bay into neighboring Baldwin County, Alabama. Interstate 10 leaves downtown through the George Wallace Tunnel under the river and then over the bay across the Jubilee Parkway to Spanish Fort/Daphne. US 98 leaves downtown through the Bankhead Tunnel under the river onto Blakeley Island and then over the bay across the Battleship Parkway into Spanish Fort, Alabama. US 90 travels over the Cochrane-Africatown USA Bridge to the north of downtown onto Blakeley Island where it becomes co-routed with US 98.[129]

Mobile's public transportation is the Wave Transit System which features buses with 18 fixed routes and neighborhood service.[130] The Wave Transit System also operates the Moda! electric trolley service in downtown Mobile with 22 stops Monday through Saturday.[131] Baylinc is a public transportation bus service provided by the Baldwin Rural Transit System in cooperation with the Wave Transit System that provides service between eastern Baldwin County and downtown Mobile. Baylinc operates Monday through Friday.[132] Greyhound Lines provides intercity bus service between Mobile and many locations throughout the United States. Mobile is served by several taxi and limousine services.[133]

Water

The Port of Mobile has public, deepwater terminals with direct access to 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of inland and intracoastal waterways serving the Great Lakes, the Ohio and Tennessee river valleys (via the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway), and the Gulf of Mexico.[134] The Alabama State Port Authority owns and operates the public terminals at the Port of Mobile.[134] The public terminals handle containerized, bulk, breakbulk, roll-on/roll-off, and heavy lift cargoes.[134] The port is also home to private bulk terminal operators, as well as a number of highly specialized shipbuilding and repair companies with two of the largest floating dry docks on the Gulf Coast.[134]

The city is home port for Carnival Cruise Lines' MS Holiday cruise ship which sails on four and five day itineraries through the Western Caribbean from the Alabama Cruise Terminal on Water Street.[135]

Media

- See also: Media in Mobile, Alabama

Mobile's Press-Register is Alabama's oldest active newspaper, dating back to 1813.[136] The paper focuses on Mobile and Baldwin counties and the city of Mobile, but also serves southwestern Alabama and southeastern Mississippi.[136] Mobile's alternative newspaper is the Lagniappe.[137] The Mobile area's local magazine is Mobile Bay Monthly.[138]

Television

Mobile is served locally by four television stations: WPMI 15 (NBC), WKRG 5 (CBS), WALA 10 (FOX), and WBPG 55 (CW).[139] The regional area is also served by WEAR 3 (ABC) and WJTC 44, an independent station. They are both based in Pensacola, Florida. Mobile is included in the Mobile-Pensacola-Fort Walton Beach designated market area, as defined by Nielsen Media Research, and is ranked 61st in the United States for the 2007-08 television season.[140]

Radio

Thirteen FM radio stations transmit from Mobile: WABB-FM, WAVH, WBHY, WBLX, WDLT, WHIL, WKSJ, WKSJ-HD2, WMXC, WMXC-HD2, WQUA, WRKH, and WRKH-HD2. Nine AM radio stations transmit from Mobile: WABB, WBHY, WGOK, WIJD, WLPR, WLVV, WMOB, WNTM, and WXQW. The content ranges from Christian Contemporary to Hip hop to Top 40.[141] Arbitron ranks Mobile's radio market as 93rd in the United States as of autumn 2007.[142]

Sports

- See also: History of sports in Mobile, Alabama.

Mobile is the home of Ladd-Peebles Stadium. The football stadium opened in 1948. With a current capacity of 40,646, Ladd-Peebles Stadium is the 4th largest stadium in the state.[143] Ladd-Peebles Stadium has been home to the Senior Bowl since 1951, featuring the best college seniors in NCAA football.[144] The GMAC Bowl has been played since 1999 featuring opponents from the Mid-American Conference and Conference USA.[145] Since 1988, Ladd-Peebles Stadium has hosted the Alabama-Mississippi All-Star Classic. The top graduating high school seniors from their respective states compete each June.[146] The public Mobile Tennis Center includes over 50 courts, all lighted and hard-court.[147] For golfers, Magnolia Grove, part of the Robert Trent Jones Golf Trail, has 36 holes. The Falls course was recently named the best par 3 course in America.[148] Since 1999, the LPGA Tournament of Champions has been played annually at Magnolia Grove. The Crossings course is home of this tournament. Beginning in 2008, the Bell Micro LPGA Classic will also be held in Mobile. Mobile is also home to the Azalea Trail Run, which races through historic midtown and downtown Mobile. This 10k run has been an annual event since 1978.[149] The Azalea Trail Run is one of the premier 10k road races in the U.S., attracting runners from all over the world.[150] Mobile's Hank Aaron Stadium is the home of the Mobile BayBears minor league baseball team.[151] As of December 2007, Mobile's University of South Alabama approved a NCAA Football program to be played at Ladd-Peebles Stadium.[152]

International sister cities

Mobile has international links with the following cities:[153][154]

|

See also

- Mobile in popular culture

- People from Mobile

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Mobile County, Alabama

- Gaillard Island- Bird Habitat

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 ""Mobile Alabama"". "GNIS Feature Query Results". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 ""2000 census for Mobile, Alabama"". "U.S. Census Bureau". Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 ""Population of Metropolitan Statistical Areas"". "U.S. Census Bureau 2000 MSA Populations". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ "USA: Alabama". CityPopulation.de. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- ↑ ""Population of Combined Statistical Areas"" (PDF). "U.S. Census Bureau 2000 CSA Populations". Retrieved on 2007-12-01.

- ↑ ""The Old Mobile Project Newsletter"" (PDF). "University of South Alabama Center for Archaeological Studies". Retrieved on 2007-11-19.

- ↑ U.S. History, Retrieved May 5, 2007

- ↑ ""Mobile Alabama"". "Britannica Online". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Drechsel, Emanuel. Mobilian Jargon: Linguistic and Sociohistorical Aspects of a Native American Pidgin. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. ISBN 0198240333

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 ""Tonnage for Selected U.S. Ports in 2006"". "U.S. Army Corps of Engineers: Waterborne Commerce Statistics". Retrieved on 2008-03-20.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 ""General Information"". "Mobile Museum of Art". Retrieved on 2007-10-23.

- ↑ 12.0 12.1 "Cultural". SeniorsResourceGuide.com. Retrieved on 2007-05-05.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 ""Mobile Mardi Gras Timeline"". "The Museum of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-11-14.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 14.2 Higginbotham, Jay. Old Mobile: Fort Louis de la Louisiane, 1702-1711,pages 106-107. Museum of the City of Mobile, 1977. ISBN 0914334034.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city,pages 20-21. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city,pages 17-27. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 17.2 17.3 "Other Locations: Historic Fort Conde" (history), Museum of Mobile, Mobile, Alabama, 2006, webpage:MoM-Other

- ↑ ""Historic Fort Conde"". "Museum of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ ""Early European Conquests and the Settlement of Mobile"". "Alabama Department of Archives and History". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ ""Mobile: Alabama's Tricentennial City"". "Alabama Department of Archives and History". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 Thomason, Michael. Mobile: the new history of Alabama's first city,pages 44-45. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 Delaney, Caldwell. The Story of Mobile, page 45. Mobile, Alabama: Gill Press, 1953. ISBN 0940882140

- ↑ ""James Wilkinson"". "War of 1812". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 24.3 24.4 24.5 24.6 24.7 Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city, page 65. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city, pages 79-80. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ ""Population of the 100 Largest Urban Places: 1860"". "U.S. Bureau of the Census ". Retrieved on 2007-11-02.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 ""Census Data for the Year 1860"". "Inter-University Consortium for Political and Social Research". Retrieved on 2007-11-13.

- ↑ ""H. L. Hunley"". "Naval Historical Center". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city, page 113. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ Delaney, Caldwell. The Story of Mobile, pages 144-146. Mobile, Alabama: Gill Press, 1953. ISBN 0940882140

- ↑ Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city, page 153. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city, page 145. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 33.2 33.3 33.4 33.5 33.6 33.7 Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city, pages 154-169. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 34.2 34.3 Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city, pages 213-217. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city, pages 260-261. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ 36.0 36.1 ""Mobile Wins Title of All American City"". "City of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 ""2005 State of the City" "". "City of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-11-15.

- ↑ ""Austal USA, Mobile AL Construction Record"". "The Colton Company ". Retrieved on 2007-11-02.

- ↑ "US Gazetteer files: 2000 and 1990". United States Census Bureau (2005-05-03). Retrieved on 2008-01-31.

- ↑ ""Alabama: Place: Population, Housing Units, Area, and Density"". "U.S. Census Bureau". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ ""Welcome to Mobile"" (PDF). "Mobile Chamber of Commerce". Retrieved on 2007-11-30.

- ↑ "Climate Normals" (PDF). National Climatic Data Centre. Retrieved on 2007-12-04.

- ↑ 43.0 43.1 Thompsen, Andrea (May 22, 2007) "Study Reveals Top 10 Wettest U.S. Cities."

- ↑ "Evolution of a Central Gulf Coast Heavy Snowband". NOAA.gov. Retrieved on 2007-11-09.

- ↑ "Mobile's Climate". SeniorsResourceGuide.com. Retrieved on 2007-05-05.

- ↑ ""Hurricane Frederic newspaper headlines courtesy of Hurricane City"". "Hurricane City". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ "" Powerful Hurricane Ivan Slams the IS Central Gulf Coast as an Upper Category-3 Storm"". "National Weather Service Forecast Office Mobile/Pensacola". Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ↑ ""Extremely Powerful Hurricane Katrina leaves a Historic Mark on the Gulf Coast". "National Weather Service Forecast Office Mobile/Pensacola". Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ↑ "Mobile Weather". US Travel Weather. Retrieved on 2007-12-03.

- ↑ ""History of Mardi Gras"". "Mobile Bay Convention & Visitors Bureau". Retrieved on 2007-11-29.

- ↑ ""Mardi Gras FAQS"". "Mobile Carnival Museum". Retrieved on 2007-12-02.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 ""Mardi Gras Terminology"". "Mobile Bay Convention & Visitors Bureau". Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 ""Mardi Gras - Mobile's Paradoxical Party"". "The Wisdom of Chief Slacabamorinico". Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ↑ Houston, Susan (2007-02-04). "Mobile; It Has History", The News & Observer, News & Observer Publishing Company, (Raleigh, NC). Retrieved on 2007-05-22.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 ""History"". "Mobile Carnival Museum". Retrieved on 2007-11-17.

- ↑ "Joe Cain Articles" (newspaper story), Joe Danborn & Cammie East, Mobile Register, 2001, webpage: CMW-history.

- ↑ ""National African American Archives and Museum"". "Alabama Bureau of Tourism and Travel". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ ""USA Archives"". "University of South Alabama". Retrieved on 2007-10-24.

- ↑ ""Mobile Municipal Archives"". "City of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-10-24.

- ↑ ""MGS library"". "The Mobile Genealogical Society ". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ ""Local History and Genealogy"". "Mobile Public Library". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ ""St. Ignatius Archives and Museum"". "PastPerfect Museum Software Newsletter January 2004". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ Mobile Saenger Theater History, Retrieved May 5, 2007

- ↑ "Setting the Stage: Mobile Opera offers a three show season for 2007-08". Press Register.

- ↑ ""Arthur C. Outlaw Convention Center"" (PDF). "www.mobile.org". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ ""About BayFest"". "Bayfest, Inc.". Retrieved on 2008-01-12.

- ↑ ""See Courage Up Close"". "USS Alabama Battleship Commission". Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ↑ ""About Us"". "Museum of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ↑ ""OakleighMuseum"". "Historic Mobile Preservation Society". Retrieved on 2007-09-26.

- ↑ Andrews, Casandra, "Master of make-Believe", Press Register, Mobile, Alabama: 28 January 2007.

- ↑ ""Tour"". "Bragg Mitchell Mansion". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ ""Welcome"". "Richards DAR House Museum". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ ""Conde"". "Conde-Charlotte Museum House". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ ""Welcome to the Mobile Medical Museum"". "Mobile Medical Museum". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ ""Phoenix Fire Museum"". "Museum of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ ""Mobile Police Department Museum"". "Mobile Police Department". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ ""About Us"". "Gulf Coast Exploreum". Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ↑ Motyka, John. "You Can Call It the Little Easy". New York Times. Retrieved on 2007-05-08.

- ↑ ""Explore the Gardens"". "Mobile Botanical Gardens". Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ↑ ""About Us"". "Bellingrath Gardens and Home Website". Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ↑ ""5 Rivers Delta Resource Center"" (PDF). "Mobile Bay Convention and Visitors Bureau". Retrieved on 2007-10-16.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 82.2 ""Parks and Recreation"". "City of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ↑ Delaney, Caldwell. The Story of Mobile,page 79. Mobile, Alabama: Gill Press, 1953.

- ↑ ""Main Street Mobile"". "Dauphin Street Virtual Walking Tour". Retrieved on 2007-09-26.

- ↑ ""Mobile Attractions"". "www.al.com". Retrieved on 2007-11-17.

- ↑ ""Historic Districts Maps from the Mobile Historical Development Commission"". "Alabama Historical Commission". Retrieved on 2007-09-21.

- ↑ Sledge, John (April 2002), "Church Street Graveyard", The Alabama Review 55: 96–105

- ↑ ""Welcome to the Magnolia Cemetery Website"". "Magnolia Cemetery website". Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ↑ ""The Story of Magnolia Cemetery"". "City of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-11-18.

- ↑ Sledge, John Sturdivant. Cities of Silence: A Guide to Mobile's Historic Cemeteries, pages 24-26. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- ↑ Sledge, John Sturdivant. Cities of Silence: A Guide to Mobile's Historic Cemeteries, pages 66-79. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- ↑ Sledge, John Sturdivant. Cities of Silence: A Guide to Mobile's Historic Cemeteries, pages 80-89. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: University of Alabama Press, 2002.

- ↑ 93.0 93.1 93.2 93.3 93.4 93.5 93.6 93.7 93.8 ""2006 census estimates for Mobile, Alabama"". "U.S. Census Bureau". Retrieved on 2007-10-14.

- ↑ ""City Officials"". "City of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ Thomason, Michael. Mobile : the new history of Alabama's first city, pages 272-273. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2001. ISBN 0817310657

- ↑ "Dean Congratulates Sam Jones, First Black Mayor of Mobile, Alabama on Victory". "Democrats.org (2005-09-16). Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ↑ ""Elected Officials"". "City of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-11-17.

- ↑ ""New Master Plan Coming for Mobile"". "City of Mobile" (10 January 2008). Retrieved on 2008-01-28.

- ↑ ""Roster of the Alabama State Senate"". "Official Website Of The Alabama Legislature". Retrieved on 2007-11-30.

- ↑ ""Roster of the Alabama House of Representatives"". "Official Website Of The Alabama Legislature". Retrieved on 2007-11-30.

- ↑ " "About Us"". "Mobile County Public School System". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ ""About ASMS"". "Alabama School of Math and Science". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ 103.0 103.1 103.2 ""Mobile's Private Schools"". "Private Schools Report". Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

- ↑ ""Mobile Alabama Colleges and Universities"". "U.S. College Search". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ ""Schools, Colleges, Departments"". "University of South Alabama". Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

- ↑ ""History of the College"". "Spring Hill College". Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

- ↑ ""Graduate Studies"". "Spring Hill College". Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

- ↑ ""Undergraduate Studies"". "Spring Hill College". Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

- ↑ ""About Us"". "University of Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

- ↑ ""Bachelor Degrees Mobile Campus"". "Faulkner University". Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

- ↑ ""Associate Degrees Mobile Campus"". "Faulkner University". Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

- ↑ ""Academic Programs"". "Bishop State Community College". Retrieved on 2007-10-25.

- ↑ 113.0 113.1 113.2 ""Healthcare"". "Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce". Retrieved on 2008-01-28.

- ↑ ""Children’s Hospital and Residential Services"". "AltaPointe Health Systems". Retrieved on 2008-02-02.

- ↑ ""Nursing Homes in Mobile, Alabama"". "Alabama Nursing Home Association". Retrieved on 2008-01-29.

- ↑ ""Mobile: Economy"". "City-Data.com". Retrieved on 2007-12-28.

- ↑ ""Local Area Unemployment Statistics - Alabama"". "Bureau of Labor Statistics". Retrieved on 2008-04-04.

- ↑ ""ALABAMA SENATE APPROVES PORT FUNDING - ALABAMA STATE PORT AUTHORITY POISED TO LET NEW CONTAINER TERMINAL CONTRACTS"". "Alabama State Port Authority (2005-05-17). Retrieved on 2007-05-09.

- ↑ ""New Shipbuilding Facility"". "Austal USA". Retrieved on 2007-10-19.

- ↑ 120.0 120.1 ""Mobile County Wins ThyssenKrupp Plant"". "Press Register". Retrieved on 2007-05-11.

- ↑ ""Northrop/EADS wins tanker contract"". "al.com.". Retrieved on 2008-02-29.

- ↑ ""Northrop beats out Boeing, wins tanker deal"". "Seattle Post Intelligencer.com". Retrieved on 2008-02-29.

- ↑ ""EADS wins $40bn US aircraft deal"". "BBC news.com". Retrieved on 2008-02-29.

- ↑ 124.0 124.1 ""Mobile Airport Authority FAQs"". "Mobile Airport Authority website". Retrieved on 2007-12-06.

- ↑ 125.0 125.1 125.2 ""MAA Properties Overview"". "Mobile Airport Authority". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ 126.0 126.1 ""Infrastructure: Rail Overview"". "Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce". Retrieved on 2007-11-17.

- ↑ Amtrak (2005-09-02). "Modified Amtrak Service to and from the Gulf Coast to be in Effect Until Further Notice". Retrieved on 2007-12-06.

- ↑ Amtrak (2007-04-02). "Sunset Limited timetable" (PDF). Retrieved on 2007-06-19.

- ↑ 129.0 129.1 ""Alabama Roads"" (PDF). "Milebymile.com". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ ""Wave Transit Buses"". "The Wave Transit System". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ ""Wave Transit moda!"". "The Wave Transit System". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ ""Baylinc Facts"" (PDF). "The Wave Transit System". Retrieved on 2007-11-06.

- ↑ ""Mobile City Guide"". "AL.com". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ 134.0 134.1 134.2 134.3 ""Infrastructure: Seaport Transportation"". "Mobile Area Chamber of Commerce". Retrieved on 2007-11-17.

- ↑ ""The Holiday"". "Carnival Cruise Lines". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ 136.0 136.1 "Newhouse News Service - The Press-Register" (description), Newhouse News Service, 2007, webpage:NH-Register.

- ↑ ""About us"". "Lagniappe, Something Extra For Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ ""Mobile Bay Monthly"". "PMT Publishing". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ ""Television in Mobile"". "www.thecityofmobile.com". Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ ""Local Television Market Universe Estimates"". "www.nielsenmedia.com". Retrieved on 2007-11-17.

- ↑ "Radio in Mobile". TheCityOfMobile.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-20.

- ↑ "Arbitron Radio Market Rankings: Fall 2007" (PDF). Arbitron.com. Retrieved on 2007-11-17.

- ↑ "Ladd-Peebles Stadium". LaddPeeblesStadium.com. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- ↑ "The Senior Bowl". Seniorbowl.com. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- ↑ "Game Recaps". GMACbowl.com. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- ↑ "History of the Alabama-Mississippi All-Star Classic". ahsaasports.com. Retrieved on 2007-04-23.

- ↑ ""Mobile Tennis Center"". "Tennis in Mobile". Retrieved on 2007-10-15.

- ↑ "Magnolia Grove". RTJgolf.com. Retrieved on 2007-05-05.

- ↑ "Event Calendar". CityOfMObile.org. Retrieved on 2007-04-30.

- ↑ "Azalea Trail Run". VulcanTri.com. Retrieved on 2007-05-05.

- ↑ ""Hank Aaron Stadium"". "Mobile Bay Bears". Retrieved on 2007-10-18.

- ↑ ""Proposal for NCAA-Football at USA"". "University of South Alabama". Retrieved on 2008-03-03.

- ↑ "Online Directory: Alabama, USA". SisterCities.org. Retrieved on 2007-11-17.

- ↑ "Regional Overview" (PDF). MobileChamber.com. Retrieved on 2007-10-15.

External links

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|