West Bank

|

||

|

JENIN

Jenin

TULKARM

Tulkarm

Tubas

TUBAS

Nablus

Shomron

Qalqiliya

QALQILYA

Salfit

Ramallah and al-Bireh

Matte Binyamin

MODI'IN ILLIT

Biq'at HaYarden

Jericho

Jerusalem

BETAR ILLIT

Gush Etzion

Bethlehem

Megilot

Hebron

Har Hebron

YATTA

|

||

The West Bank (Arabic: الضفة الغربية, aḍ-Ḍiffä l-Ġarbīyä, Hebrew: הגדה המערבית, Hagadah Hamaaravit), also known as "Judea and Samaria", is a landlocked territory on the west bank of the Jordan River in the Middle East. To the west, north, and south the West Bank shares borders with mainland Israel. To the east, across the Jordan River, lies the country of Jordan. The West Bank also contains a significant coast line along the western bank of the Dead Sea. Since 1967 most of the West Bank has been under Israeli military occupation.

Prior to the First World War, the area now known as the West Bank was under Ottoman rule as part of the province of Syria. In the 1920 San Remo conference, the victorious Allied powers allocated the area to the British Mandate of Palestine. The 1948 Arab-Israeli War saw the establishment of Israel in parts of the former Mandate, while the West Bank was captured and annexed by Jordan. The 1949 Armistice Agreements defined its interim boundary. From 1948 until 1967, the area was under Jordanian rule, and Jordan did not officially relinquish its claim to the area until 1988. Jordan's claim was never recognized by the international community, with the exception of the United Kingdom and Pakistan. The West Bank was captured by Israel [1][2] during the Six-Day War. With the exception of East Jerusalem, the West Bank was not annexed by Israel. Most of the residents are Arabs, although a large number of Israeli settlements have been built in the region since 1967.

Contents |

Origin of the name

West Bank

The region did not have a separate existence until 1948–1949, when it was defined by the Armistice Agreement between Israel and Jordan. The name "West Bank" was apparently first used by Jordanians at the time of their annexation of the region, and has become the most common name used in English and related languages. The term literally means 'the West bank of the river Jordan'; the Kingdom of Jordan being on the 'East bank' of this same River Jordan.

Cisjordan

The neo-Latin name Cisjordan or Cis-Jordan (literally "on the west side of the [River] Jordan") is the usual name in the Romance languages and Hungarian. The analogous Transjordan has historically been used to designate the region now comprising the state of Jordan which lies on the "other side" of the River Jordan. In English, the name Cisjordan is also occasionally used to designate the entire region between the Jordan River and the Mediterranean Sea, particularly in the historical context of the British Mandate and earlier times. The use of Cisjordan to refer to the smaller region discussed in this article, while common in scholarly fields including archaeology, is rare in general English usage; the name West Bank is standard usage for this geo-political entity. For the low-lying area immediately west of the Jordan, the name Jordan Valley is used instead.

Political terminology

Israelis refer to the region either as a unit: "The West Bank" (Hebrew: "ha-Gada ha-Ma'aravit" "הגדה המערבית"), or as two units: Judea and Samaria (Hebrew: "Yehuda" "יהודה", "Shomron" "שומרון"), after the two biblical kingdoms (the southern Kingdom of Judah and the northern Kingdom of Israel — the capital of which was, for a time, in the town of Samaria). The geographic terms Judea and Samaria have been in continual use by Jews since biblical times. Arab geography also refers to the northern part of the West Bank as ‘’as-Samara’’. However, the name has become somewhat obsolete among Arabs due its politicised use by the Israeli settler movement.

The Arab world and especially the Palestinians strongly object to the term Judea and Samaria, the use of which they deem to reflect Israeli expansionist aims. Instead, they refer to the area as "the occupied West Bank of the Jordan River",[3] emphasizing that the area is under Israeli military control and jurisdiction (see "occupied Palestinian territories").

History

The territory now known as the West Bank was a part of the British Mandate of Palestine entrusted to the United Kingdom by the League of Nations after World War I. The terms of the Mandate called for the creation in Palestine of a Jewish national home without prejudicing the civil and religious rights of the non-Jewish population of Palestine.[4]

The current border of the West Bank was not a dividing line of any sort during the Mandate period, but rather the armistice line between the forces of the neighboring kingdom of Jordan and those of Israel at the close of the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. When the United Nations General Assembly voted in 1947 to partition Palestine into a Jewish State, an Arab State, and an internationally-administered enclave of Jerusalem, a more broad region of the modern-day West Bank was assigned to the Arab State. The West Bank was controlled by Iraqi and Jordanian forces at the end of the 1948 War and the area was annexed by Jordan in 1950 but this annexation was recognized only by the United Kingdom (Pakistan is often, but apparently falsely,[5] assumed to have recognized it also). The idea of the an independent Palestinian state was not on the table. King Abdullah of Jordan was crowned King of Jerusalem and granted Palestinian Arabs in the West Bank and East Jerusalem Jordanian citizenship.[6]

During the 1950s, there was a significant influx of Palestinian refugees and violence together with Israeli reprisal raids across the Green Line.

In May 1967 Egypt ordered out U.N. peacekeeping troops and re-militarized the Sinai peninsula, and blockaded the straits of Tiran. Fearing an Egyptian attack, the government of Levi Eshkol attempted to restrict any confrontation to Egypt alone. In particular it did whatever it could to avoid fighting Jordan. However, "carried along by a powerful current of Arab nationalism", on May 30, 1967 King Hussein flew to Egypt and signed a mutual defense treaty in which the two countries agreed to consider "any armed attack on either state or its forces as an attack on both".[2][7] Fearing an imminent Egyptian attack, on June 5, the Israel Defense Forces launched a pre-emptive attack on Egypt[8] which began what came to be known as the Six Day War.

Jordan soon began shelling targets in west Jerusalem, Netanya, and the outskirts of Tel Aviv.[1] Despite this, Israel sent a message promising not to initiate any action against Jordan if it stayed out of the war. Hussein replied that it was too late, "the die was cast".[2] On the evening of June 5 the Israeli cabinet convened to decide what to do; Yigal Allon and Menahem Begin argued that this was an opportunity to take the Old City of Jerusalem, but Eshkol decided to defer any decision until Moshe Dayan and Yitzhak Rabin could be consulted.[9] Uzi Narkis made a number of proposals for military action, including the capture of Latrun, but the cabinet turned him down. The Israeli military only commenced action after Government House was captured, which was seen as a threat to the security of Jerusalem.[10] On June 6 Dayan encircled the city, but, fearing damage to holy places and having to fight in built-up areas, he ordered his troops not to go in. However, upon hearing that the U.N. was about to declare a ceasefire, he changed his mind, and without cabinet clearance, decided to take the city.[9] After fierce fighting with Jordanian troops in and around the Jerusalem area, Israel captured the Old City on June 7.

No specific decision had been made to capture any other territories controlled by Jordan. After the Old City was captured, Dayan told his troops to dig in to hold it. When an armored brigade commander entered the West Bank on his own initiative, and stated that he could see Jericho, Dayan ordered him back. However, when intelligence reports indicated that Hussein had withdrawn his forces across the Jordan river, Dayan ordered his troops to capture the West Bank.[10] Over the next two days, the IDF swiftly captured the rest of the West Bank and blew up the Abdullah and Hussein Bridges over the Jordan, thereby severing the West Bank from the East.[11] According to Narkis:

First, the Israeli government had no intention of capturing the West Bank. On the contrary, it was opposed to it. Second, there was not any provocation on the part of the IDF. Third, the rein was only loosened when a real threat to Jerusalem's security emerged. This is truly how things happened on June 5, although it is difficult to believe. The end result was something that no one had planned.[12]

The Arab League's Khartoum conference in September declared continuing belligerency, and stated the league's principles of "no peace with Israel, no recognition of Israel, no negotiations with it". [13] In November, 1967, UN Security Council Resolution 242 was unanimously adopted, calling for "the establishment of a just and lasting peace in the Middle East" to be achieved by "the application of both the following principles:" "Withdrawal of Israeli armed forces from territories occupied in the recent conflict" (see semantic dispute) and: "Termination of all claims or states of belligerency" and respect for the right of every state in the area to live in peace within secure and recognised boundaries. Egypt, Jordan, Israel and Lebanon entered into consultations with the UN Special representative over the implementation of 242.[14] The text did not refer to the PLO or to any Palestinian representative because none was recognized at that time.

In 1988, Jordan ceded its claims to the West Bank to the Palestine Liberation Organization, as "the sole legitimate representative of the Palestinian people."[15][16]

Administration

The 1993 Oslo Accords declared the final status of the West Bank to be subject to a forthcoming settlement between Israel and the Palestinian leadership. Following these interim accords, Israel withdrew its military rule from some parts of the West Bank, which was divided into three areas:

| Area | Control | Administration | % of WB land |

% of WB Palestinians |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | Palestinian | Palestinian | 17% | 55% |

| B | Israeli | Palestinian | 24% | 41% |

| C | Israeli | Israeli | 59% | 4%[17] |

Area A comprises Palestinian towns, and some rural areas away from Israeli population centers in the north (between Jenin, Nablus, Tubas, and Tulkarm), the south (around Hebron), and one in the center south of Salfit. Area B adds other populated rural areas, many closer to the center of the West Bank. Area C contains all the Israeli settlements, roads used to access the settlements, buffer zones (near settlements, roads, strategic areas, and Israel), and almost all of the Jordan Valley and Judean Desert.

Areas A and B are themselves divided among 227 separate areas (199 of which are smaller than 2 square kilometres (1 sq mi)) that are separated from one another by Israeli-controlled Area C. [18] Areas A, B, and C cross the 11 Governorates used as administrative divisions by the Palestinian National Authority and named after major cities.

While the vast majority of the Palestinian population lives in areas A and B, the vacant land available for construction in dozens of villages and towns across the West Bank is situated on the margins of the communities and defined as area C. [19]

The Palestinian Authority has full civil control in area A, area B is characterized by joint-administration between the PA and Israel, while area C is under full Israeli control. Israel maintains overall control over Israeli settlements, roads, water, airspace, "external" security and borders for the entire territory

Demographics

The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics estimated that approximately 2.5 million Palestinians live in the West Bank (including Israeli-annexed East Jerusalem) at the end of 2006.[20], though a recent study by the American-Israel Demographic Research Group disputes these figures (see #Recent developments). In December 2007, an official Census conducted by the Palestinian Authority found that the Palestinian population of the West Bank (including Israeli-annexed East Jerusalem) was 2,345,000.[21]

There are over 275,000 Israeli settlers living in the West Bank, as well as around 200,000 living in Israeli-annexed East Jerusalem. There are also small ethnic groups, such as the Samaritans living in and around Nablus, numbering in the hundreds. Interactions between the two societies have generally declined following the Palestinian Intifadas, though an economic relationship often exists between adjacent Israeli and Palestinian Arab villages.

As of October 2007, around 23,000 Palestinians in the West Bank work in Israel every day with another 9,200 working in Israeli settlements. In addition, around 10,000 Palestinian traders from the West Bank are allowed to travel every day into Israel.[22]

Approximately 30% of Palestinians living in the West Bank are refugees or descendants of refugees from villages and towns located in what became Israel during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War (see Palestinian exodus).[23][24][25]

Significant population centers

| Center | Population |

|---|---|

| Al-Bireh | 40,000 |

| Betar Illit | 29,355 |

| Bethlehem | 30,000 |

| Gush Etzion | 40,000 |

| Hebron (al-Khalil) | 120,000 |

| Jericho (Ariha) | 25,000 |

| Jenin | 47,000 |

| Ma'ale Adummim | 33,259 |

| Modi'in Illit | 34,514 |

| Nablus | 135,000 |

| Qalqilyah | 40,000 |

| Ramallah | 23,000 |

| Tulkarm | 75,000 |

| Yattah | 42,000 |

The most densely populated part of the region is a mountainous spine, running north-south, where the Palestinian cities of Nablus, Ramallah, al-Bireh, Abu Dis, Bethlehem, Hebron and Yattah are located as well as the Israeli settlements of Ariel, Ma'ale Adumim and Betar Illit. Ramallah, although relatively small in population compared to other major cities, serves as an economic and political center for the Palestinians. Jenin in the extreme north of the West Bank is on the southern edge of the Jezreel Valley. Modi'in Illit, Qalqilyah and Tulkarm are in the low foothills adjacent to the Israeli Coastal Plain, and Jericho and Tubas are situated in the Jordan Valley, north of the Dead Sea.

Transportation and communication

Roads

The West Bank has 4,500 km (2,796 mi) of roads, of which 2,700 km (1,678 mi) are paved.

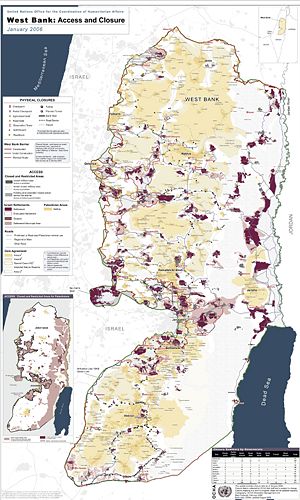

In response to shootings by Palestinians, some highways, especially those leading to Israeli settlements, are completely inaccessible to cars with Palestinian license plates, while many other roads are restricted only to public transportation and to Palestinians who have special permits from Israeli authorities.[26][27][28] Due to numerous shooting assaults targeting Israeli vehicles, the IDF bars Israelis from using most of the original roads in the West Bank. Israel's longstanding policy of separation-to-prevent-friction dictates the development of alternative highway systems for Israelis and Palestinian traffic.

Israel maintains about 500 checkpoints or roadblocks in the region.[29] . As such, movement restrictions are also placed on main roads traditionally used by Palestinians to travel between cities, and such restrictions have been blamed for poverty and economic depression in the West Bank.[30] Since the beginning of 2005, there has been some amelioration of these restrictions. According to recent human rights reports, "Israel has made efforts to improve transport contiguity for Palestinians travelling in the West Bank. It has done this by constructing underpasses and bridges (28 of which have been constructed and 16 of which are planned) that link Palestinian areas separated from each other by Israeli settlements and bypass roads"[31] and by removal of checkpoints and physical obstacles, or by not reacting to Palestinian removal or natural erosion of other obstacles. "The impact (of these actions) is most felt by the easing of movement between villages and between villages and the urban centres".[31]

However, the obstacles encircling major Palestinian urban hubs, particularly Nablus and Hebron, have remained. In addition, the IDF prohibits Israeli citizens from entering Palestinian-controlled land (Area A).

As of August 2007, a divided highway is currently under construction that will pass through the West Bank. The highway has a concrete wall dividing the two sides, one designated for Israeli vehicles, the other for Palestinian. The wall is designed to allow Palestinians to freely pass north-south through Israeli-held land. [32]

Airports

The West Bank has three paved airports which are currently for military use only. Palestinians were previously able to use Israel's Ben Gurion International Airport with permission; however, Israel has discontinued issuing such permits, and Palestinians wishing to travel must cross the land border to either Jordan (via the Allenby Bridge) or Egypt in order to use airports located in these countries.[33]

Telecom

As transportation between the Palestinian cities became very difficult, due to hundreds of Israeli military checkpoints on Palestinian roads, telephone and internet play a more important role in the Palestinian daily life for communication.

The Israeli Bezeq and Palestinian PalTel Group telecommunication companies provide communication services in the West Bank. The Palestinian mobile market was until 2007 monopolized by Jawwal. As the number of internet users is increasing rapidly (year 2005 160.000 users Numerous Palestinian websites are growing to helping the Palestinians communicate and trade through the internet like:

News Agencies

Ma'an News

PNN

WAFA

Bethlehem News

Market

Sayarti for Used Cars in Palestine

Palestine Shop for Traditional Products

Tatreez for Palestinian Embroidery

Radio and television

The Palestinian Broadcasting Corporation broadcasts from an AM station in Ramallah on 675 kHz; numerous local privately owned stations are also in operation. Most Palestinian households have a radio and TV, and satellite dishes for receiving international coverage are widespread. Recently, PalTel announced and has begun implementing an initiative to provide ADSL broadband internet service to all households and businesses.

Israel's cable television company 'HOT', satellite television provider (DBS) 'Yes', AM & FM radio broadcast stations and public television broadcast stations all operate. Broadband internet service by Bezeq's ADSL and by the cable company are available as well.

The Al-Aqsa Voice broadcasts from Dabas Mall in Tulkarem at 106.7 FM. The Al-Aqsa TV station shares these offices.

Higher education

Before 1967 there were no universities in the West Bank (except for the Hebrew University in Jerusalem - see below). There were a few lesser institutions of higher education; for example, An-Najah, which started as an elementary school in 1918 and became a community college in 1963. As the Jordanian government did not allow the establishment of such universities in the West Bank, Palestinians could obtain degrees only by travelling abroad to places such as Jordan, Lebanon, or Europe.

After the region was captured by Israel in the Six-Day War, several educational institutions began offering undergraduate courses, while others opened up as entirely new universities. In total, seven Universities have been commissioned in the West Bank since 1967:

- Bethlehem University, a Roman Catholic institution partially funded by the Vatican, opened its doors in 1973 [3].

- In 1975, Birzeit College (located in the town of Bir Zeit north of Ramallah) became Birzeit University after adding third- and fourth-year college-level programs [4].

- An-Najah College in Nablus likewise became An-Najah National University in 1977 [5].

- The Hebron University was established in 1980 [6]

- Al-Quds University, whose founders had yearned to establish a university in Jerusalem since the early days of Jordanian rule, finally realized their goal in 1995 [7].

- Also in 1995, after the signing of the Oslo Accords, the Arab American University—the only private university in the West Bank—was founded right outside of Zababdeh, with the purpose of providing courses according to the American system of education [8].

- In 2005, the Israeli government recommended to upgrade the College of Judea and Samaria in Ariel to become a full fledged university [9]. This move to create a university within an Israeli settlement has angered some Palestinians, although no official response was made by the Palestinian authority.

- The Hebrew University of Jerusalem, established in 1918, is one of Israel's oldest, largest, and most important institutes of higher learning and research. During the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, the leader of the Palestinian forces in Jerusalem, Abdul Kader Husseini, threatened that the Hadassah Hospital and the Hebrew University would be captured or destroyed "if the Jews continued to use them as bases for attacks".[34] Medical convoys between the Yishuv-controlled section of Jerusalem and Mount Scopus were attacked since December 1947.[35] After the Hadassah medical convoy massacre in 1948, which also included university staff, the Mount Scopus campus was cut off from the Jewish part of Jerusalem. After the War, the University was forced to relocate to a new campus in Givat Ram in western Jerusalem. After Israel captured East Jerusalem in the Six-Day War of June 1967, the University returned to its original campus in Mount Scopus. [Note that Mount Scopus is technically not part of the West Bank as it is an internationally-recognized Israeli enclave within the West Bank].

Most universities in the West Bank have politically active student bodies, and elections of student council officers are normally along party affiliations. Although the establishment of the universities was initially allowed by the Israeli authorities, some were sporadically ordered closed by the Israeli Civil Administration during the 1970s and 1980s to prevent political activities and violence against the IDF. Some universities remained closed by military order for extended periods during years immediately preceding and following the first Palestinian Intifada, but have largely remained open since the signing of the Oslo Accords despite the advent of the Al-Aqsa Intifada in 2000.

The founding of Palestinian universities has greatly increased education levels among the population in the West Bank. According to a Birzeit University study, the percentage of Palestinians choosing local universities as opposed to foreign institutions has been steadily increasing; as of 1997, 41% of Palestinians with bachelor degrees had obtained them from Palestinian institutions.[36] According to UNESCO, Palestinians are one of the most highly educated groups in the Middle East "despite often difficult circumstances".[37] The literacy rate among Palestinians in the West Bank (and Gaza) (89%) is third highest in the region after Israel (95%) and Jordan (90%).[38][39][40]

Status

- See also: Political status of the West Bank and Gaza Strip

Legal status

The West Bank is currently considered under international law to be, de jure, a territory not part of any state. The United Nations Security Council,[41] the United Nations General Assembly,[42] the International Court of Justice,[43] and the International Committee of the Red Cross[44] refer to it as occupied by Israel.

According to Alan Dowty, legally the status of the West Bank falls under the international law of belligerent occupation, as distinguished from nonbelligerent occupation that follows an armistice. This assumes the possibility of renewed fighting, and affords the occupier "broad leeway". The West Bank has a unique status in two respects; first, there is no precedent for a belligerent occupation lasting for more than a brief period, and second, that the West Bank was not part of a sovereign country before occupation — thus, in legal terms, there is no "reversioner" for the West Bank. This means that sovereignty of the West Bank is currently suspended, and, according to some, Israel, as the only successor state to the Palestine Mandate, has a status that "goes beyond that of military occupier alone."[45]

The current status arises from the facts (see above reference) that Great Britain surrendered its mandate in 1948 and Jordan relinquished its claim in 1988. Since the area has never in modern times been an independent state, there is no "legitimate" claimant to the area other than the present occupier, which currently happens to be Israel. This argument however is not accepted by the international community and international lawmaking bodies, virtually all of whom regard Israel's activities in the West Bank and Gaza as an occupation that denies the fundamental principle of self-determination found in the Article One of the United Nations Charter, and in the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights. Further, UN Security Council Resolution 242 notes the "inadmissibility of the acquisition of territory by war" regardless of whether the war in which the territory was acquired was offensive or defensive. Prominent Israeli human rights organizations such as B'tselem also refer to the Israeli control of the West Bank and Gaza as an occupation.[46] John Quigley has noted that "...a state that uses force in self-defense may not retain territory it takes while repelling an attack. If Israel had acted in self-defense, that would not justify its retention of the Gaza Strip and West Bank. Under the UN Charter there can lawfully be no territorial gains from war, even by a state acting in self-defense. The response of other states to Israel's occupation shows a virtually unanimous opinion that even if Israel's action was defensive, its retention of the West Bank and Gaza Strip was not."[47]

Political positions

The future status of the West Bank, together with the Gaza Strip on the Mediterranean shore, has been the subject of negotiation between the Palestinians and Israelis, although the current Road Map for Peace, proposed by the "Quartet" comprising the United States, Russia, the European Union, and the United Nations, envisions an independent Palestinian state in these territories living side by side with Israel (see also proposals for a Palestinian state). However, the "Road Map" states that in the first phase, Palestinians must end all terror and attacks on Israel, whereas Israel must dismantle outposts. Since neither condition has been met since the Road Map was "accepted," by all sides, final negotiations have not yet begun on major political differences.

The Palestinian Authority believes that the West Bank ought to be a part of their sovereign nation, and that the presence of Israeli military control is a violation of their right to Palestinian Authority rule. The United Nations calls the West Bank and Gaza Strip Israeli-occupied (see Israeli-occupied territories). The United States State Department also refers to the territories as occupied.[48][49][50] Many Israelis and their supporters prefer the term disputed territories, because they claim part of the territory for themselves, and state the land has not, in 2000 years, been sovereign.

Israel argues that its presence is justified because:

- Israel's eastern border has never been defined by anyone;

- The disputed territories have not been part of any state (Jordanian annexation was never officially recognized) since the time of the Ottoman Empire;

- According to the Camp David Accords (1978) with Egypt, the 1994 agreement with Jordan and the Oslo Accords with the PLO, the final status of the territories would be fixed only when there was a permanent agreement between Israel and the Palestinians.

Palestinian public opinion opposes Israeli military and settler presence on the West Bank as a violation of their right to statehood and sovereignty.[51] Israeli opinion is split into a number of views:

- Complete or partial withdrawal from the West Bank in hopes of peaceful coexistence in separate states (sometimes called the "land for peace" position); (According to a 2003 poll 76% of Israelis support a peace agreement based on that principle).[52]

- Maintenance of a military presence in the West Bank to reduce Palestinian terrorism by deterrence or by armed intervention, while relinquishing some degree of political control;

- Annexation of the West Bank while considering the Palestinian population as (for instance) citizens of Jordan with Israeli residence permit as per the Elon Peace Plan;

- Annexation of the West Bank and assimilation of the Palestinian population to fully fledged Israeli citizens;

- Transfer of the East Jerusalem Palestinian population (a 2002 poll at the height of the Al Aqsa intifada found 46% of Israelis favoring Palestinian transfer of Jerusalem residents;[53] in 2005 two polls using a different methodology put the number at approximately 30%).[54]

Accession of West Bank to Jordan

There has been a proposal of the West Bank's accession to Jordan by the people of Jordan, Palestine and even Israel. It is also supported by Pakistan, Turkey and Syria.

Annexation

Israel annexed the territory of East Jerusalem, and its Palestinian residents (if they should decline Israeli citizenship) have legal permanent residency status.[55][56] Although permanent residents are permitted, if they wish, to receive Israeli citizenship if they meet certain conditions including swearing allegiance to the State and renouncing any other citizenship, most Palestinians did not apply for Israeli citizenship for political reasons.[57] There are various possible reasons as to why the West Bank had not been annexed to Israel after its capture in 1967. The government of Israel has not formally confirmed an official reason, however, historians and analysts have established a variety of such, most of them demographic. Among the most agreed upon:

- Reluctance to award its citizenship to an overwhelming number of a potentially hostile population whose allies were sworn to the destruction of Israel [58][59][60]

- Fear that the population of non-Zionist Arabs would outnumber the Israelis, appeal to different political interests, and vote Israel out of existence; thus failing to maintain the concept and safety of a Jewish state [61][62]

- To ultimately exchange land for peace with neighbouring states[58][59]

Settlements and international law

Israeli settlements on the West Bank beyond the Green Line border are considered by some legal scholars to be illegal under international law.[63][64][65][66] Other legal scholars[67] including Julius Stone,[68] have argued that the settlements are legal under international law, on a number of different grounds. The Independent reported in March 2006 that immediately after the 1967 war Theodor Meron, legal counsel of Israel's Foreign Ministry advised Israeli ministers in a "top secret" memo that any policy of building settlements across occupied territories violated international law and would "contravene the explicit provisions of the Fourth Geneva Convention".[69][70] A contrasting opinion was held by Eugene Rostow, a former Dean of the Yale Law School and undersecretary of state for political affairs in the administration of U.S. President Lyndon Johnson, who wrote in 1991 that Israel has a right to have settlements in the West Bank under 1967's UN Security Council Resolution 242.[71] The European Union[72] and the Arab League consider the settlements to be illegal. Israel also recognizes that some small settlements are "illegal" in the sense of being in violation of Israeli law.[73][74]

Although Israel has formally pledged to stop settlement efforts in the West Bank as part of internationally-backed peace efforts, it has failed to honor the commitment and construction has continued to grow.[75] Israel has also stopped monitoring new construction at the settlements.[76]

In 2005 the United States ambassador to Israel, Dan Kurtzer, expressed U.S. support "for the retention by Israel of major Israeli population centres [in the West Bank] as an outcome of negotiations",[77] reflecting President Bush's statement a year earlier that a permanent peace treaty would have to reflect "demographic realities" on the West Bank.[78]

The UN Security Council has issued several non-binding resolutions addressing the issue of the settlements. Typical of these is UN Security Council resolution 446 which states [the] practices of Israel in establishing settlements in the Palestinian and other Arab territories occupied since 1967 have no legal validity, and it calls on Israel as the occupying Power, to abide scrupulously by the 1949 Fourth Geneva Convention.[79]

The Conference of High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention held in Geneva on 5 December, 2001 called upon "the Occupying Power to fully and effectively respect the Fourth Geneva Convention in the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including East Jerusalem, and to refrain from perpetrating any violation of the Convention." The High Contracting Parties reaffirmed "the illegality of the settlements in the said territories and of the extension thereof."[80]

On December 30, 2007, Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Olmert issued an order requiring approval by both the Israeli Prime Minister and Israeli Defense Minister of all settlement activities (including planning) in the West Bank.[81]

West Bank barrier

The Israeli West Bank barrier is a physical barrier being constructed by Israel consisting of a network of fences with vehicle-barrier trenches surrounded by an on average 60 metres (197 ft) wide exclusion area (90%) and up to 8 metres (26 ft) high concrete walls (10%) (although in most areas the wall is not nearly that high).[82] It is located mainly within the West Bank, partly along the 1949 Armistice line, or "Green Line" between the West Bank and Israel. As of April 2006 the length of the barrier as approved by the Israeli government is 703 kilometers (436 miles) long. Approximately 58.4% has been constructed, 8.96% is under construction, and construction has not yet begun on 33% of the barrier.[83] The space between the barrier and the green line is a closed military zone known as the Seam Zone, cutting off 8.5% of the West Bank and encompassing tens of villages and tens of thousands of Palestinians.[84].[85]

The barrier generally runs along or near the 1949 Jordanian-Israeli armistice/Green Line, but diverges in many places to include on the Israeli side several of the highly populated areas of Jewish settlements in the West Bank such as East Jerusalem, Ariel, Gush Etzion, Emmanuel, Karnei Shomron, Givat Ze'ev, Oranit, and Maale Adumim.

The barrier is a very controversial project. Supporters claim the barrier is a necessary tool protecting Israeli civilians from the Palestinian attacks that increased significantly during the al-Aqsa Intifada;[86][87] it has helped reduce incidents of terrorism by 90% from 2002 to 2005; over a 96% reduction in terror attacks in the six years ending in 2007,[88] though Israel's State Comptroller has acknowledged that most of the suicide bombers crossed into Israel through existing checkpoints [10]. Its supporters claim that the onus is now on the Palestinian Authority to fight terrorism.[89]

Opponents claim the barrier is an illegal attempt to annex Palestinian land under the guise of security,[90] violates international law,[91] has the intent or effect to pre-empt final status negotiations,[92] and severely restricts Palestinians who live nearby, particularly their ability to travel freely within the West Bank and to access work in Israel, thereby undermining their economy.[93] According to a 2007 World Bank report, the Israeli occupation of the West Bank has destroyed the Palestinian economy, in violation of the 2005 Agreement on Movement and Access. All major roads (with a total length of 700 km) are basically off-limits to Palestinians, making it impossible to do normal business. Economic recovery would reduce Palestinian dependence on international aid by one billion dollars per year. [94]

Pro-settler opponents claim that the barrier is a sly attempt to artificially create a border that excludes the settlers, creating "facts on the ground" that justify the mass dismantlement of hundreds of settlements and displacement of over 100,000 Jews from the land they claim as their biblical homeland.[95]

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "On June 5, Israel sent a message to Hussein urging him not to open fire. Despite shelling into western Jerusalem, Netanya, and the outskirts of Tel Aviv, Israel did nothing." The Six Day War and Its Enduring Legacy, Washington Institute for Near East Policy, July 2, 2002.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "In May-June 1967 Eshkol's government did everything in its power to confine the confrontation to the Egyptian front. Eshkol and his colleagues took into account the possibility of some fighting on the Syrian front. But they wanted to avoid having a clash with Jordan and the inevitable complications of having to deal with the predominantly Non-Jewish Arab population of the West Bank. The fighting on the eastern front was initiated by Jordan, not by Israel. King Hussein got carried along by a powerful current of Arab nationalism. On 30 May he flew to Cairo and signed a defense pact with Nasser. On 5 June, Jordan started shelling the Israeli side in Jerusalem. This could have been interpreted either as a salvo to uphold Jordanian honor or as a declaration of war. Eshkol decided to give King Hussein the benefit of the doubt. Through General Odd Bull, the Norwegian commander of UNTSO, he sent the following message the morning of 5 June: 'We shall not initiate any action whatsoever against Jordan. However, should Jordan open hostilities, we shall react with all our might, and the king will have to bear the full responsibility of the consequences.' King Hussein told General Bull that it was too late; the die was cast." Avi Shlaim, The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World, W. W. Norton & Company, 2000, pp. 243-244.

- ↑ Alan Cowell, Special To The New York Times (Published: November 16, 1988). "Arafat Urges U.S. To Press Israelis To Negotiate Now - New York Times". Query.nytimes.com. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ The Palestine Mandate

- ↑ Beyond the Veil, Israel-Pakistan Relations P. R. Kumuraswami.

- ↑ Armstrong, Karen. Jerusalem: One City, Three Faiths. New York: Ballantine Books, 1996. p. 387.

- ↑ Michael Oren, Six Days of War, Oxford University Press, 2002, ISBN 0195151747, p. 130

- ↑ Pre-emptive strike:

- "In a pre-emptive attack on Egypt..." Israel and the Palestinians in depth, 1967: Six Day War, BBC website. URL accessed May 14, 2006.

- "a massive pre-emptive strike on Egypt." BBC on this day, BBC website. URL accessed May 14, 2006.

- "Israel launched a pre-emptive strike on June 5" Mideast 101: The Six Day War, CNN website. URL accessed May 14, 2006.

- "Most historians now agree that although Israel struck first, this pre-emptive strike was defensive in nature." The Mideast: A Century of Conflict Part 4: The 1967 Six Day War, NPR morning edition, October 3, 2002. URL accessed May 14, 2006.

- "a massive preemptive strike by Israel that crippled the Arabs’ air capacity." SIX-DAY WAR, Funk & Wagnalls® New Encyclopedia. © 2006 World Almanac Education Group via The History Channel website, 2006, URL accessed February 17, 2007.

- "In a pre-emptive strike, Israel smashed its enemies’ forces in just six days..." Country Briefings: Israel, The Economist website, Jul 28th 2005. URL accessed March 15, 2007.

- "Yet pre-emptive strikes can often be justified even if they don't meet the letter of the law. At the start of the Six-Day War in 1967, Israel, fearing that Egypt was aiming to destroy the Jewish state, devastated Egypt's air force before its pilots had scrambled their jets." Strike First, Explain Yourself Later Michael Elliott, Time, Jul. 01, 2002. URL accessed March 15, 2007.

- "the situation was similar to the crisis that preceded the 1967 Six Day war, when Israel took preemptive military action." Delay with Diplomacy, Marguerite Johnson, Time, May 18, 1981. URL accessed March 15, 2007.

- "Israel made a preemptive attack against a threatened Arab invasion..." Six-Day War, Encarta Answers, URL accessed April 10, 2007.

- "Israel preempted the invasion with its own attack on June 5, 1967." Six-Day War, Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia 2007. URL accessed April 10, 2007.

- "In 1967, Egypt ordered the UN troops out and blocked Israeli shipping routes - adding to already high levels of tension between Israel and its neighbours." Israel and the Palestinians in depth, 1967: Six Day War, BBC website. URL accessed May 14, 2006.

- "In June 1967, Egypt, Syria and Jordan massed their troops on Israel's borders in preparation for an all-out attack." Mideast 101: The Six Day War, CNN website. URL accessed May 14, 2006.

- "Nasser... closed the Gulf of Aqaba to shipping, cutting off Israel from its primary oil supplies. He told U.N. peacekeepers in the Sinai Peninsula to leave. He then sent scores of tanks and hundreds of troops into the Sinai closer to Israel. The Arab world was delirious with support," The Mideast: A Century of Conflict Part 4: The 1967 Six Day War, NPR morning edition, October 3, 2002. URL accessed May 14, 2006.

- "War returned in 1967, when Egypt, Syria and Jordan massed forces to challenge Israel." Country Briefings: Israel, The Economist website. URL accessed March 3, 2007.

- "After Israel declared its statehood, several Arab states and Palestinian groups immediately attacked Israel, only to be driven back. In 1956 Israel overran Egypt in the Suez-Sinai War. Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser vowed to avenge Arab losses and press the cause of Palestinian nationalism. To this end, he organized an alliance of Arab states surrounding Israel and mobilized for war." Six-Day War, Microsoft® Encarta® Online Encyclopedia 2007. URL accessed April 10, 2007.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 Shlaim, 2000, p. 244.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 Shlaim, 2000, p. 245.

- ↑ Benny Morris, Righteous Victims, pp. 324-5

- ↑ Shlaim, 2000, p. 246.

- ↑ League of Arab States, Khartoum Resolution, 1 September 1967

- ↑ "See Security Council Document S/10070 Para 2.".

- ↑ "Address to the Nation". Kinghussein.gov.jo. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "West Bank - MSN Encarta". Encarta.msn.com. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "JURIST - Palestinian Authority: Palestinian law, legal research, human rights". Jurist.law.pitt.edu. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "The West Bank and Gaza: A Population Profile - Population Reference Bureau". Prb.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "B'Tselem - Publications - Land Grab: Israel's Settlement Policy in the West Bank, May 2002". Btselem.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ The Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics

- ↑ "Palestinians grow by a million in decade". The Jerusalem Post (February 2008). Retrieved on 2008-10-08.

- ↑ Israel labour laws apply to Palestinian workers

- ↑ "UNRWA in Figures: Figures as of 31 December 2004" (PDF). United Nations (April 2005). Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ "Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics". Palestinian National Authority Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (2007).

- ↑ Ksenia Svetlova (December 1, 2005). "Can trust be rebuilt?". The Jerusalem Post. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ http://www.humanitarianinfo.org/opt/docs/UN/OCHA/OCHAoPt_ClosureAnalysis0106_En.pdf

- ↑ "A/57/366/Add.1 of 16 September 2002". Domino.un.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ YESHA. "A/57/366 of 29 August 2002". Domino.un.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS | Middle East | New plan for W Bank checkpoints". News.bbc.co.uk (30 April 2008). Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ http://www.reliefweb.int/library/documents/2005/ocha-opt-26apr.pdf

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 http://www.humanitarianinfo.org/opt/docs/UN/OCHA/ochaHU0805_En.pdf

- ↑ Erlanger, Steven. A Segregated Road in an Already Divided Land, The New York Times, (2007-08-11). Retrieved on 2007-08-11.

- ↑ "MIFTAH-Israel bars Palestinians from using Ben-Gurion airport". Miftah.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ 'Husseini Threatens Hadassah', The Palestine Post, 18 March, 1948, p. 1.

- ↑ The Palestine Post, 14 April, 1948, p. 3

- ↑ "chapter 4??" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "UNESCO | Education - Palestinian Authority". Portal.unesco.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ http://www.undp.org/hdr2003/indicator/indic_2_1_1.html

- ↑ [1]

- ↑ "CIA - The World Factbook - West Bank". Cia.gov. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Resolution 446, Resolution 465, Resolution 484, among others

- ↑ "Applicability of the Geneva Convention relative to the Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War, of 12 August 1949, to the Occupied Palestinian Territory, including Jerusalem, and the other occupied Arab territories". United Nations (December 17, 2003). Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ "Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory". International Court of Justice (July 9, 2004). Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ "Conference of High Contracting Parties to the Fourth Geneva Convention: statement by the International Committee of the Red Cross". International Committee of the Red Cross (December 5, 2001). Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ Dowty, 2001, p. 217.

- ↑ "B'Tselem - Land Expropriation and Settlements in the International Law". Btselem.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Quigley, The Case for Palestine, 2005, p. 172

- ↑ "Jordan (03/08)". State.gov. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "Israel". State.gov. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "Israel and the Occupied Territories". State.gov. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "PSR Survey". Retrieved on 2007-04-16.

- ↑ "Israeli public opinion regarding the conflict". The Center for Middle East Peace and Economics Cooperation. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ Asher Arian (June 2002). "A Further Turn to the Right: Israeli Public Opinion on National Security - 2002". Strategic Assessment (Tel Aviv University: Jaffee Center for Strategic Studies) 5 (1): 50–57. http://www.tau.ac.il/jcss/sa/v5n1p4Ari.html. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ Aaron Klein (February 24, 2005). "Suppressed poll released following WND story: Results show plurality of Israelis favor booting Palestinians". WorldNetDaily. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ Yael Stein (April 1997). "The Quiet Deportation: Revocation of Residency of East Jerusalem Palestinians" (

DOC). Joint report by Hamoked & B'Tselem. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

DOC). Joint report by Hamoked & B'Tselem. Retrieved on 2006-09-27. - ↑ Yael Stein (April 1997). "The Quiet Deportation: Revocation of Residency of East Jerusalem Palestinians (Summary)". Joint report by Hamoked & B'Tselem. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ "Legal status of East Jerusalem and its residents". B'Tselem. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ 58.0 58.1 Bard

- ↑ 59.0 59.1 David Bamberger (1985, 1994). A Young Person's History of Israel. USA: Behrman House. pp. 182. ISBN 0-87441-393-1.

- ↑ "What Occupation?". Palestine Facts. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ Bard

- ↑ (Bard"Our Positions: Solving the Palestinian/Israeli Conflict". Free Muslim Coalition Against Terrorism. Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ Emma Playfair (Ed.) (1992). International Law and the Administration of Occupied Territories. USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 396. ISBN 0-19-825297-8.

- ↑ Cecilia Albin (2001). Justice and Fairness in International Negotiation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 150. ISBN 0-521-79725-X.

- ↑ Mark Gibney; Stanlislaw Frankowski (1999). Judicial Protection of Human Rights: Myth or Reality?. Westport, CT: Praeger/Greenwood. pp. 72. ISBN 0-275-96011-0.

- ↑ 'Plia Albeck, legal adviser to the Israeli Government was born in 1937. She died on September 27, 2005, aged 68', The Times, October 5, 2005, p. 71.

- ↑ "FAQ on Israeli settlements". CBC News (February 26, 2004). Retrieved on 2006-09-27.

- ↑ "International Law" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Donald Macintyre, 'Israelis were warned on illegality of settlements in 1967 memo', The Independent (London), March 11, 2006, p. 27.

- ↑ "Israelis Were Warned on Illegality of Settlements in 1967 Memo". Commondreams.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ "Resolved: are the settlements legal? Israeli West Bank policies". Tzemachdovid.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ [2] EU Committee Report. Retrieved April 19, 2007

- ↑ Diplomatic and Legal Aspects of the Settlement Issue, Jerusalem Issue Brief, Vol. 2, No. 16, 19 January, 2003.

- ↑ How to Respond to Common Misstatements About Israel: Israeli Settlements, Anti-Defamation League website. URL accessed April 10, 2006.

- ↑ BBC November 2007

- ↑ BBC November 2007

- ↑ 'US will accept Israel settlements', BBC News Online, 25 March, 2005.

- ↑ 'UN Condemns Israeli settlements', BBC News Online, 14 April, 2005.

- ↑ UNSC Resolution 446 (1979) of 22 March 1979

- ↑ Implementation of the Fourth Geneva Convention in the occupied Palestinian territories: history of a multilateral process (1997-2001), International Review of the Red Cross, 2002 - No. 847.

- ↑ "Olmert curbs WBank building, expansion and planning", Reuters (2007-12-31). Retrieved on 2007-12-31.

- ↑ Israel High Court Ruling Docket H.C.J. 7957/04

- ↑ "B'Tselem - The Separation Barrier - Statistics". Btselem.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Margarat Evans (2006-01-06). "Indepth Middle East:Israel's Barrier". CBC. Retrieved on 2007-11-05.

- ↑ "Israel's Separation Barrier:Challenges to the Rule of Law and Human Rights: Executive Summary Part I and II". International Commission of Jurists (6 July 2004). Retrieved on 2007-05-11.

- ↑ "Israel Security Fence - Ministry of Defense". Securityfence.mod.gov.il. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

- ↑ Map of Palestine - Land of Israel, 1845

- ↑ Wall Street Journal, "After Sharon", January 6, 2006.

- ↑ Sen. Clinton: I support W. Bank fence, PA must fight terrorism

- ↑ Under the Guise of Security, B'Tselem]

- ↑ "U.N. court rules West Bank barrier illegal" (CNN)

- ↑ Set in stone, The Guardian, June 15, 2003

- ↑ The West Bank Wall - Unmaking Palestine

- ↑ Movement and access restrictions in the West Bank: Uncertainty and inefficiency in the Palestinian economy. World Bank Technical Team. May 9, 2007.

- ↑ "Women in Green - What We Say". Womeningreen.org. Retrieved on 2008-10-09.

References

- Albin, Cecilia (2001). Justice and Fairness in International Negotiation. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-79725-X

- Bamberger, David (1985, 1994). A Young Person's History of Israel. Behrman House. ISBN 0-87441-393-1

- Dowty, Alan (2001). The Jewish State: A Century Later. University of California Press. ISBN 0520229118

- Oren, Michael (2002). Six Days of War, Oxford University Press. ISBN 0195151747

- Gibney, Mark and Frankowski, Stanislaw (1999). Judicial Protection of Human Rights. Praeger/Greenwood. ISBN 0-275-96011-0

- Playfair, Emma (Ed.) (1992). International Law and the Administration of Occupied Territories. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-825297-8

- Shlaim, Avi (2000). The Iron Wall: Israel and the Arab World, W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 0393048160

- Howell, Mark (2007). What Did We Do to Deserve This? Palestinian Life under Occupation in the West Bank, Garnet Publishing. ISBN 1859641954

See also

- Rule of the West Bank and East Jerusalem by Jordan

- Economy of the West Bank

- Geography of the West Bank

- Second Intifada

- Israeli West Bank barrier

- West Bank Closures

External links

- West Bank from the CIA World Factbook

- Palestine Facts & Info from Palestinian Academic Society for the Study of International Affairs

- The Legal Status of Palestine Under International Law (Supports Palestinian claims), a publication by Birzeit University.

- United Nations - Question of Palestine

- Disputed Territories: Forgotten Facts about the West Bank and Gaza Strip - from the Israeli government

- The Westbank Dispute Analysis from ProCon

- Large map of West Bank (1992)

- MOVING UP: An Aliyah Journal, the new book, is an upbeat account about Aliyah and life in Israel.

- A series of geopolitical maps of the West Bank

- "American Thinker" opinion article which disputes some of the data in this article

- 1988 "Address to the Nation" by King Hussein of Jordan Ceding Jordanian Claims to the West Bank to the PLO

- Camden Abu Dis Friendship Association - establishing links between the North London Borough of Camden and the town of Abu Dis in the West Bank

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||