Migration Period

The Migration Period, also called Barbarian Invasions, or sometimes Völkerwanderung (German for "wandering of peoples") is the English name used by historians to a human migration which occurred within the period of roughly AD 300–700 in Europe,[1] marking the transition from Late Antiquity to the Early Middle Ages. The migration included the Goths, Vandals, Bulgars, Alans, Suebi, Frisians and Franks, among other Germanic, Iranian and Slavic tribes. The migration may have been triggered by the incursions of the Huns, in turn connected to the Turkic migration in Central Asia, population pressures, or climate changes.

Migrations would continue well beyond AD 1000, with successive waves of Slavs, Avars, Hungarians, the Turkic expansion and, finally, the Mongol invasions, radically changing the ethnic makeup of Eastern Europe. Western European historians tend to emphasize the earlier migrations most relevant to Western Europe.

Contents |

Modern account

The migration movement may be divided into two phases; the first phase, between AD 300 and 500, largely seen from the Mediterranean perspective of Greek and Latin historians,[2] with the aid of some archaeology, put Germanic peoples in control of most areas of the former Western Roman Empire. (See also: Ostrogoths, Visigoths, Burgundians, Alans, Langobards, Angles, Saxons, Jutes, Suebi, Alamanni, Vandals). The first to formally enter Roman territory — as refugees from the Huns — were the Visigoths in 376. Tolerated by the Romans on condition that they defend the Danube frontier, they rebelled, eventually invading Italy and sacking Rome itself (410) before settling in Iberia and founding a kingdom there that endured 300 years. They were followed into Roman territory by the Ostrogoths led by Theodoric the Great, who settled in Italy itself.

In Gaul, the Franks, a fusion of western Germanic tribes whose leaders had been strongly aligned with Rome, entered Roman lands more gradually and peacefully during the 5th century, and were generally accepted as rulers by the Roman-Gaulish population. Fending off challenges from the Allemanni, Burgundians and Visigoths, the Frankish kingdom became the nucleus of the future states of France and Germany. Meanwhile Roman Britain was more slowly conquered by Angles and Saxons.

The second phase, between AD 500 and 700, saw Slavic tribes settling in Central and Eastern Europe, particularly in eastern Magna Germania, and gradually making it predominantly Slavic. The Bulgars, who had been present in far eastern Europe since the second century, conquered the eastern Balkan territory of the Byzantine Empire in the seventh century. The Lombards, a Germanic people, settled northern Italy in the region now known as Lombardy.

The Arabs tried to invade Europe via Asia Minor in the second half of the seventh century and the early eighth century, but were eventually defeated at the siege of Constantinople by the joint forces of Byzantium and Bulgars in 717-18. Khazars stopped the Arab expansion into Eastern Europe across the Caucasus. At the same time, Moors invaded Europe via Gibraltar, conquering Hispania (the Iberian Peninsula) from the Visigoths in 711 before finally being halted by the Franks at the Battle of Tours in 732. These battles largely fixed the frontier between Christendom and Islam for the next three centuries.

During the eighth to tenth centuries, not usually counted as part of the Migration Period but still within the Early Middle Ages, new waves of migration, first of the Magyars and later of the Turkic peoples, as well as Viking expansion from Scandinavia, threatened the newly established order of the Frankish Empire in Central Europe.

Migration vs invasion

The German term Völkerwanderung [ˈfœlkɐˌvandəʁʊŋ] ("migration of peoples") is still used as an alternative label for the Migration Period in English-language historiography.[3] However, the term Völkerwanderung is also strongly associated with a certain romantic historical style which has strong roots in the German-speaking world of the 19th century. The Völkerwanderung is seen an indication of cultural energy and dynamism. This analysis became associated with nineteenth century German Romantic nationalism.

Even the term "barbarian invasion" is still in use in some English works.[4] It has its roots in the Latin point of view on the migration period: whereas Germans and Slavic peoples use the term "migration" (Völkerwanderung in German, Stěhování národů in Czech, etc.), in cultures speaking Latin-derived languages (French, Italian, Spanish, etc.), these migrations are called "barbarian invasions" (e.g. the Italian term Invasioni barbariche). "Barbarian" historically has the neutral meaning of "foreigner"[5][6] but it also has a pejorative meaning of "uncivilized" and "cruel" (cf. Russian "варвар"), making it problematic as a neutral historical descriptor. Even the old romantic vision of the Migration age differs between differing cultures: on one side the Völkerwanderung, the myth of young and vigorous people who succeeded the old and decadent Roman society; on the other side the stereotype of uncivilized and savage 'barbarians', who destroyed the highly developed Roman civilization, starting a Dark Age of disorder and violence.

Today, the notion of the "invasions" of pre-Romantic-generation historians has also fallen out of favour; many scholars today hold that a great deal of the migration did not represent hostile invasion so much as tribes taking the opportunity to enter and settle lands already thinly populated, in part by the recurring pandemic of the Plague of Justinian, which made its first appearance in 541-42 Territories were weakly held by a divided Roman state whose economy was shrinking at a time when the climate was cooling (see Migration Period Pessimum). While there were certainly battles, and sieges of cities, and deaths of innocent civilians fought between the tribes and the Roman peoples, the migration period did not see the kind of wholesale destruction carried out in later centuries by the Mongols or by industrial-era armies. Some twentieth-century English-language historiography largely abandoned the German and Latin terms, replacing them with the term "Migration Period", arguing that it is more neutral, as in the series Studies in Historical Archaeoethnology or Gyula László's The Art of the Migration Period.

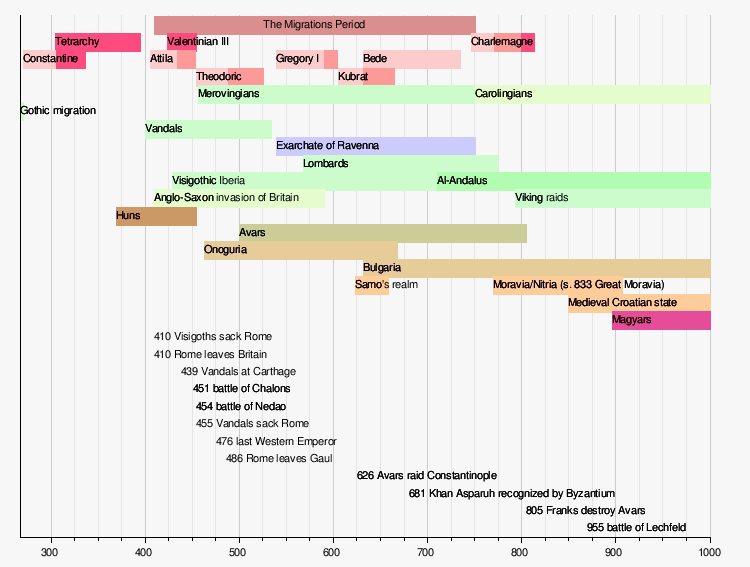

Timeline

See also

- Arnold J. Toynbee

- Dark Ages

- Decline of the Roman Empire

- History of Western civilization

- Early Middle Ages

- Getica

- Gothic and Vandal warfare

- Historical migration

- Human migration

- Late Antiquity

- Magyar invasions of Europe

- Medieval demography

- Migration Period art

- Muslim conquests

- Reidgotaland

- Sassanid dynasty

- Tatar invasions

Notes

- ↑ Precise dates given may vary; often cited is 410, the sack of Rome by Alaric I and 751, the accession of Pippin the Short and the establishment of the Carolingian Dynasty.

- ↑ Even Jordanes, an Alan or Goth by birth, wrote in Latin.

- ↑ "Jene Epoche, in der sich der Übergang von der Spätantike zum Frühmittelalter vollzog, wird in der deutschen Wissenschaftssprache traditionell als 'Völkerwanderungszeit' bezeichnet." Translation: "That epoch in which the transition from Late Antiquity to the early Middle Ages took place is traditionally called "Völkerwanderungszeit", or "migration time", in the German academic language". Manuel Koch, Das Reich der Vandalen und seine Vorgeschichte(n) (The empire of the Vandals and its prehistory) [1] (in German)

- ↑ "Barbarian Invasions" is still a commonly used and accepted term for this period. See for example Katherine Fischer Drew, "Barbarians, Invasions Of" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages, edited by Joseph Strayer, Vol.2 1983

- ↑ Encyclopædia Britannica, 15th Ed., Vol. 20 (Macropædia), page 742, right column, line 57 ff. (Chicago, 1989)

- ↑ Webster's New Universal Unabridged Dictionary, page 149, voice "Barbarian" (New York, 1983)

References

- J.B. Bury: History of the Later Roman Empire. 2 vols. London 1923.

- Guy Halsall: Barbarian Migrations and the Roman West. Cambridge 2007.

- Walter Pohl: Die Völkerwanderung. Eroberung und Integration. Stuttgart 2002.