Melatonin

|

|

|

|

|

Melatonin

|

|

| Systematic (IUPAC) name | |

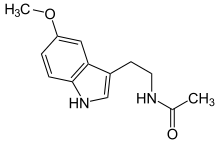

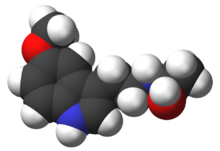

| N-[2-(5-methoxy-1H-indol-3-yl)ethyl] ethanamide |

|

| Identifiers | |

| CAS number | |

| ATC code | N05 |

| PubChem | |

| DrugBank | |

| ChemSpider | |

| Chemical data | |

| Formula | C13H16N2O2 |

| Mol. mass | 232.278 g/mol |

| Pharmacokinetic data | |

| Bioavailability | 30 – 50% |

| Metabolism | Hepatic via CYP1A2 mediated 6-hydroxylation |

| Half life | 35 to 50 minutes |

| Excretion | Urine |

| Therapeutic considerations | |

| Pregnancy cat. |

? |

| Legal status |

POM(UK) |

| Routes | ? |

Melatonin (pronounced /ˌmɛ lə ˈtoʊ nən/ melatonin), also known chemically as N-acetyl-5-methoxytryptamine [1], is a naturally occurring hormone found in most animals, including humans, and some other living organisms, including algae.[2] Circulating levels vary in a daily cycle, and melatonin is important in the regulation of the circadian rhythms of several biological functions.[3] Many biological effects of melatonin are produced through activation of melatonin receptors,[4] while others are due to its role as a pervasive and powerful antioxidant[5] with a particular role in the protection of nuclear and mitochondrial DNA.[6]

The use of melatonin as a drug can entrain (synchronize) the circadian clock to environmental cycles and can have beneficial effects for treatment of certain insomnias. Its therapeutic potential may be limited by its short biological half-life, poor bioavailability, and the fact that it has numerous non-specific actions.[7] In recent studies though, prolonged release melatonin has shown good results in treating insomnia in older adults.[8]

Products containing melatonin have been available as a dietary supplement in the United States since 1993,[9] and met with good consumer acceptance and enthusiasm.[10] However, over-the-counter sales remain illegal in many other countries including some members of the European Union and New Zealand,[11] and the U.S. Postal Service lists melatonin among items prohibited by Germany.[12]

Contents |

Biosynthesis

In higher animals and humans, melatonin is produced by pinealocytes in the pineal gland (located in the brain) and also by the retina, lens and GI tract. It is naturally synthesized from the amino acid tryptophan (via synthesis of serotonin) by the enzyme 5-hydroxyindole-O-methyltransferase.

Production of melatonin by the pineal gland is under the influence of the suprachiasmatic nucleus (SCN) of the hypothalamus, which receives information from the retina about the daily pattern of light and darkness. Both SCN rhythmicity and melatonin production are affected by non-image-forming light information traveling through the recently-identified retinohypothalamic tract (RHT).

The light/dark information reaches the SCN via retinal photosensitive ganglion cells, intrinsically photosensitive photoreceptor cells, distinct from those involved in image forming (that is, these light sensitive cells are a third type in the retina, in addition to rods and cones). These cells represent approximately 2% of the retinal ganglion cells in humans and express the photopigment melanopsin.[13] The sensitivity of melanopsin fits with that of a vitamin A-based photopigment with a peak sensitivity at 484 nm (blue light).[14] This photoperiod cue entrains the circadian rhythm, and the resultant production of specific "dark"- and "light"-induced neural and endocrine signals regulates behavioral and physiological circadian rhythms.

Melatonin may also be produced by a variety of peripheral cells such as bone marrow cells,[15][16] lymphocytes and epithelial cells. Usually, the melatonin concentration in these cells is much higher than that found in the blood but it does not seem to be regulated by the photoperiod.

Melatonin is also synthesized by various plants, such as rice, and ingested melatonin has been shown to be capable of reaching and binding to melatonin binding sites in the brains of mammals.[17][18]

Distribution

Melatonin produced in the pineal gland acts as an endocrine hormone since it is released into the blood. By contrast, melatonin produced by the retina and the gastrointestinal (GI) tract acts as a paracrine hormone.

Roles in the animal kingdom

Many animals use the variation in duration and quantity of melatonin production each day as a seasonal clock.[19] In animals and in some conditions also in humans[20] the profile of melatonin synthesis and secretion is affected by the variable duration of night in summer as compared to winter. The change in duration of secretion thus serves as a biological signal for the organisation of daylength-dependent (photoperiodic) seasonal functions such as reproduction, behaviour, coat growth and camouflage colouring in seasonal animals.[20] In seasonal breeders which do not have long gestation periods, and which mate during longer daylight hours, the melatonin signal controls the seasonal variation in their sexual physiology, and similar physiological effects can be induced by exogenous melatonin in animals including mynah birds[21] and hamsters.[22] Melatonin can suppress libido by inhibiting secretion of luteinizing hormone (LH) and follicle stimulating hormone (FSH) from the anterior pituitary gland, especially in mammals that have a breeding season when daylight hours are long. The reproduction of long-day breeders is repressed by melatonin and the reproduction of short-day breeders is stimulated by melatonin.

During the night, melatonin regulates leptin, lowering the levels; see Leptin.

Melatonin is also related to the mechanism by which some amphibians and reptiles change the color of their skin and, indeed, it was in this connection the substance first was discovered.[23][24]

Roles in humans

Circadian rhythm

- See also: Phase response curve

In humans, melatonin is produced by the pineal gland, a gland about the size of a pea, located in the center of the brain. The melatonin signal forms part of the system that regulates the circadian cycle by chemically causing drowsiness and lowering the body temperature, but it is the central nervous system (more specifically, the suprachiasmatic nucleus) that controls the daily cycle in most components of the paracrine and endocrine systems[25][26] rather than the melatonin signal (as was once postulated).

Light dependence

Production of melatonin by the pineal gland is inhibited by light and permitted by darkness. For this reason melatonin has been called "the hormone of darkness" and its onset each evening is called the Dim-Light Melatonin Onset (DLMO). Secretion of melatonin as well as its level in the blood, peaks in the middle of the night, and gradually falls during the second half of the night, with normal variations in timing according to an individual's chronotype.

Until recent history, humans in temperate climates were exposed to only about six hours of daylight in the winter. In the modern world, artificial lighting reduces darkness exposure to typically eight or fewer hours per day all year round. Even low light levels inhibit melatonin production to some extent, but over-illumination can create significant reduction in melatonin production. Since it is principally blue light that suppresses melatonin,[27] wearing glasses that block blue light[28] in the hours before bedtime may avoid melatonin loss. Use of blue-blocking goggles the last hours before bedtime has also been advised for people who need to adjust to an earlier bedtime, as melatonin promotes sleepiness.

Melatonin levels at night are reduced to 50% by exposure to a low-level incandescent bulb for only 39 minutes, and it has been shown that women with the brightest bathrooms have an increased risk for breast cancer.[29]

Reduced melatonin production has been proposed as a likely factor in the significantly higher cancer rates in night workers.[30]

Antioxidant

Besides its primary function as synchronizer of the biological clock, melatonin may exert a powerful antioxidant activity. In many lower life forms, it serves only this purpose.[31] Melatonin is an antioxidant that easily can cross cell membranes and the blood-brain barrier.[5] Melatonin is a direct scavenger of OH, O2−, and NO.[32] Unlike other antioxidants, melatonin does not undergo redox cycling, the ability of a molecule to undergo reduction and oxidation repeatedly. Redox cycling may allow other antioxidants (such as vitamin C) to regain their antioxidant properties. Melatonin, on the other hand, once oxidized, cannot be reduced to its former state because it forms several stable end-products upon reacting with free radicals. Therefore, it has been referred to as a terminal (or suicidal) antioxidant.[33]

Recent research indicates that the first metabolite of melatonin in the melatonin antioxidant pathway may be N(1)-acetyl-N(2)-formyl-5-methoxykynuramine or AFMK rather than the common, excreted 6-hydroxymelatonin sulfate. AFMK alone is detectable in unicellular organisms and metazoans. A single AFMK molecule can neutralize up to 10 ROS/RNS since many of the products of the reaction/derivatives (including melatonin) are themselves antioxidants. This capacity to absorb free radicals extends at least to the quaternary metabolites of melatonin, a process referred to as "the free radical scavenging cascade". This is not true of other, conventional antioxidants.[31]

In animal models, melatonin has been demonstrated to prevent the damage to DNA by some carcinogens, stopping the mechanism by which they cause cancer.[34] It also has been found to be effective in protecting against brain injury caused by ROS release in experimental hypoxic brain damage in newborn rats.[35] Melatonin's antioxidant activity may reduce damage caused by some types of Parkinson's disease, may play a role in preventing cardiac arrhythmia and may increase longevity; it has been shown to increase the average life span of mice by 20% in some studies.[36][37][38]

Immune system

While it is known that melatonin interacts with the immune system,[39][40] the details of those interactions are unclear. There have been few trials designed to judge the effectiveness of melatonin in disease treatment. Most existing data are based on small, incomplete clinical trials. Any positive immunological effect is thought to result from melatonin acting on high affinity receptors (MT1 and MT2) expressed in immunocompetent cells. In preclinical studies, melatonin may enhance cytokine production,[41] and by doing this counteract acquired immunodeficiences. Some studies also suggest that melatonin might be useful fighting infectious disease[42] including viral and bacterial infections. Endogenous melatonin in human lymphocytes has been related to interleukin-2 (IL-2) production and to the expression of IL-2 receptor[43] This suggests that melatonin is involved in the clonal expansion of antigen-stimulated human T lymphocytes. When taken in conjunction with calcium, it is an immunostimulator and is used as an adjuvant in some clinical protocols; conversely, the increased immune system activity may aggravate autoimmune disorders. In rheumatoid arthritis patients, melatonin production has been found increased when compared to age-matched healthy controls.[44]

Dreaming

Many supplemental melatonin users have reported an increase in vivid dreaming. Extremely high doses of melatonin (50mg) dramatically increased REM sleep time and dream activity in both narcoleptics and those without narcolepsy. [45]However, one factor that may influence this perception is that many over-the-counter melatonin tablets also include Vitamin B6 (pyroxidine), which is also known to be capable of producing vivid dreams.

Many psychoactive drugs, such as LSD, increase melatonin synthesis.[45] It has been suggested that nonpolar (lipid-soluble) indolic hallucinogenic drugs emulate melatonin activity in the awakened state and that both act on the same areas of the brain.[45] It has been suggested that psychotropic drugs be readmitted in the field of scientific inquiry and therapy.[46] If so, melatonin may be prioritized for research in this reemerging field of psychiatry.[47]

Autism

Individuals with autism spectrum disorders (ASD) may have lower than normal levels of melatonin. A 2008 study found that unaffected parents of individuals with ASD also have lower melatonin levels, and that the deficits were associated with low activity of the ASMT gene, which encodes the last enzyme of melatonin synthesis.[48]

Current and potential medical indications

Melatonin has been studied for the treatment of cancer, immune disorders, cardiovascular diseases, depression, seasonal affective disorder (SAD), circadian rhythm sleep disorders and sexual dysfunction. Studies by Alfred J. Lewy at Oregon Health & Science University and other researchers have found that it may ameliorate circadian misalignment and SAD.[49] Basic research indicates that melatonin may play a significant role in modulating the effects of drugs of abuse such as cocaine.[50]

Treatment of circadian rhythm disorders

Exogenous melatonin, used as a chronobiotic and usually taken orally in the afternoon and/or evening, is, together with light therapy upon awakening, the standard treatment for delayed sleep phase syndrome and non-24-hour sleep-wake syndrome. See Phase response curve, PRC. It appears to have some use against other circadian rhythm sleep disorders, such as jet lag and the problems of people who work rotating or night shifts.

Preventing ischemic damage

Melatonin has been shown to reduce tissue damage in rats due to ischemia in both the brain[51] and the heart;[52] however, this has not been tested in humans.

Learning, memory and Alzheimer's

Melatonin receptors appear to be important in mechanisms of learning and memory in mice,[53] and melatonin can alter electrophysiological processes associated with memory, such as long-term potentiation (LTP). The first published evidence that melatonin may be useful in Alzheimer's disease was the demonstration that this neurohormone prevents neuronal death caused by exposure to the amyloid beta protein, a neurotoxic substance that accumulates in the brains of patients with the disorder.[54] Melatonin also inhibits the aggregation of the amyloid beta protein into neurotoxic microaggregates which seem to underlie the neurotoxicity of this protein, causing death of neurons and formation of neurofibrillary tangles, the other neuropathological landmark of Alzheimer's disease.[54]

Melatonin has been shown to prevent the hyperphosphorylation of the tau protein in rats. Hyperphosphorylation of tau protein can also result in the formation of neurofibrillary tangles. Studies in rats suggest that melatonin may be effective for treating Alzheimer's disease.[55] These same neurofibrillary tangles can be found in the hypothalamus in patients with Alzheimer's, adversely affecting their bodies' production of melatonin. Those Alzheimer's patients with this specific affliction often show heightened afternoon agitation, called sundowning, which has been shown in many studies to be effectively treated with melatonin supplements in the evening.[56]

ADHD

Research shows that after melatonin is administered to ADHD patients, the time needed to fall asleep is significantly reduced. Furthermore, the effects of the melatonin after three months showed no change from its effects after one week of use.[57]

Fertility

Recent research has concluded that melatonin supplementation in perimenopausal women produces a highly significant improvement in thyroid function and gonadotropin levels, as well as restoring fertility and menstruation and preventing the depression associated with the menopause.[58] However, at the same time, some resources warn women trying to conceive not to take a melatonin supplement.[59]

Headaches

Several clinical studies indicate that supplementation with melatonin is an effective preventive treatment for migraines and cluster headaches.[60][61]

Mental disorders

Melatonin has been shown to be effective in treating one form of depression, seasonal affective disorder, [1] and is being considered for bipolar and other disorders where circadian disturbances are involved.[62]

Other

Some studies have shown that melatonin has potential for use in the treatment of various forms of cancer, HIV, and other viral diseases; however, further testing is necessary to confirm this.[63]

Melatonin is involved in the regulation of body weight, and may be helpful in treating obesity (especially when combined with calcium).[64]

Histologically speaking, it is also believed that melatonin has some effects for sexual growth in higher organisms (quoted from Ross Histology and Wheather's Functional Histology).

Use as a dietary supplement

The primary motivation for the use of melatonin as a supplement may be as a natural aid to better sleep. Incidental benefits to health and well-being may accumulate, due to melatonin's role as an antioxidant and its stimulation of the immune system and several components of the endocrine system.

Studies from Massachusetts Institute of Technology have said that melatonin pills sold as supplements contain three to ten times the amount needed to produce the desirable physiologic nocturnal blood melatonin level for enhancement of sleep. Dosages are designed to raise melatonin levels for several hours to enhance quality of sleep, but some studies suggest that smaller doses (for example 0.3 mg as opposed to 3 mg) are just as effective at improving sleep quality.[65] Large doses of melatonin can even be counterproductive: Lewy et al[66] provide support to the "idea that too much melatonin may spill over onto the wrong zone of the melatonin phase-response curve" (PRC). In one of their subjects, 0.5 mg of melatonin was effective while 20 mg was not.

Safety of supplementation

Melatonin is available without prescription in most cases in the United States and Canada, while it is available only by prescription or not at all in some other countries. The hormone is available as oral supplements (capsules, tablets or liquid) and as transdermal patches.

In the USA, because it is sold as a dietary supplement and not as a drug, the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) regulations that apply to medications are not applicable to melatonin.[3] However, new FDA rules will, by June 2010, ensure that all production of dietary supplements must comply with current good manufacturing practices, and be manufactured with "controls that result in a consistent product free of contamination, with accurate labeling."[67] In addition, the industry is now required to report to the FDA "all serious dietary supplement related adverse events."

Melatonin appears to cause very few side effects in the short term, up to three months, when healthy people take it at low doses. A systematic review[68] in 2006 looked specifically at efficacy and safety in two categories of melatonin usage: first, for sleep disturbances which are secondary to other diagnoses and, second, for sleep disorders such as jet lag and shift work which accompany sleep restriction. These Canadian researchers found no trials showing evidence of effects on sleep onset latency in subjects with secondary sleep disorders or in subjects with disorders accompanying sleep restriction. Seventeen randomised controlled trials with 651 participants showed no evidence of adverse effects of melatonin with short term use. The study concludes: "There is evidence that melatonin is safe with short term use." In most of their analyses they are able to state that there is no significant difference between melatonin and placebo; even the most common adverse events reported; headache, dizziness, nausea and drowsiness; did not significantly differ for melatonin vs. placebo. A similar analysis[69] by the same team a year earlier on the efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin in the management of primary sleep disorders found that: "There is some evidence to suggest that melatonin is effective in treating delayed sleep phase syndrome," and that evidence suggests that melatonin is safe with short-term use, three months or less.

Some unwanted effects in some people, especially at high doses (~more than 3 mg/day) may include: headaches, nausea, next-day grogginess or irritability, hormone fluctuations, vivid dreams or nightmares[70] and reduced blood flow (see below).

While no large, long-term studies which might reveal side effects have been conducted, there do exist case reports about patients who have taken melatonin for years.[71]

If taken several hours before bedtime according to the phase response curve (PRC) for melatonin, it merely advances the phase of melatonin production. If taken 30 to 90 minutes before bedtime, it advances the period of melatonin's presence in the blood. Melatonin can cause somnolence (drowsiness), and therefore caution should be shown when driving, operating machinery, etc. When taken several hours before bedtime in accordance with the PRC for melatonin in humans, the dosage should be so tiny as to not cause tiredness/sleepiness.

In individuals with auto-immune disorders, there is concern that melatonin supplementation may ameliorate or exacerbate symptoms due to immunomodulation.[72][73]

Individuals who experience orthostatic intolerance, a cardiovascular condition that results in reduced blood pressure and blood flow to the brain when a person stands, may experience a worsening of symptoms when taking melatonin supplements, a study at Penn State College of Medicine's Milton S. Hershey Medical Center suggests. Melatonin can exacerbate symptoms by reducing nerve activity in those who experience the condition, the study found.[74]

Because of concerns of transmission of viruses through melatonin derived from animal sources, melatonin derived from cow or sheep pineal glands is no longer administered. The synthetic form does not carry this risk.[3][75]

See also

- Ramelteon

- Agomelatine

References

- ↑ http://www.sleepdex.org/melatonin.htm

- ↑ Caniato R, Filippini R, Piovan A, Puricelli L, Borsarini A, Cappelletti E (2003). "Melatonin in plants". Adv Exp Med Biol 527: 593–7. PMID 15206778.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 3.2 Altun A, Ugur-Altun B (2007). "Melatonin: therapeutic and clinical utilization". Int. J. Clin. Pract. 61 (5): 835–45. doi:. PMID 17298593.

- ↑ Boutin J, Audinot V, Ferry G, Delagrange P (2005). "Molecular tools to study melatonin pathways and actions". Trends Pharmacol Sci 26 (8): 412–9. doi:. PMID 15992934.

- ↑ 5.0 5.1 Hardeland R (2005). "Antioxidative protection by melatonin: multiplicity of mechanisms from radical detoxification to radical avoidance". Endocrine 27 (2): 119–30. doi:. PMID 16217125.

- ↑ Reiter R, Acuña-Castroviejo D, Tan D, Burkhardt S (2001). "Free radical-mediated molecular damage. Mechanisms for the protective actions of melatonin in the central nervous system". Ann N Y Acad Sci 939: 200–15. PMID 11462772.

- ↑ Turek FW, Gillette MU (November 2004). "Melatonin, sleep, and circadian rhythms: rationale for development of specific melatonin agonists". Sleep Med. 5 (6): 523–32. doi:. PMID 15511698.

- ↑ Wade AG, Ford I, Crawford G, et al (October 2007). "Efficacy of prolonged release melatonin in insomnia patients aged 55-80 years: quality of sleep and next-day alertness outcomes". Curr Med Res Opin 23 (10): 2597–605. doi:. PMID 17875243.

- ↑ Ratzburg, Courtney (Undated). "Melatonin: The Myths and Facts". Vanderbilt University. Retrieved on 2007-12-02.

- ↑ Lewis, Alan (1999). Melatonin and the Biological Clock. McGraw-Hill. pp. pp. 7. ISBN 0879837349.

- ↑ Hammell, John (1997). "CODEX: INTERNATIONAL THREAT TO HEALTH FREEDOM". Life Extension Foundation. Retrieved on 2007-11-02.

- ↑ USPS. "Country Conditions for Mailing — Germany". Retrieved on 2008-01-15.

- ↑ Nayak SK, Jegla T, Panda S (January 2007). "Role of a novel photopigment, melanopsin, in behavioral adaptation to light". Cell. Mol. Life Sci. 64 (2): 144–54. doi:. PMID 17160354.

- ↑ Roberts JE (2005). "Update on the positive effects of light in humans". Photochem. Photobiol. 81 (3): 490–2. doi:. PMID 15656701.

- ↑ Maestroni GJ (March 2001). "The immunotherapeutic potential of melatonin". Expert Opin Investig Drugs 10 (3): 467–76. doi:. PMID 11227046.

- ↑ Conti A, Conconi S, Hertens E, Skwarlo-Sonta K, Markowska M, Maestroni JM (May 2000). "Evidence for melatonin synthesis in mouse and human bone marrow cells". J. Pineal Res. 28 (4): 193–202. doi:. PMID 10831154. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/openurl?genre=article&sid=nlm:pubmed&issn=0742-3098&date=2000&volume=28&issue=4&spage=193.

- ↑ Hattori A, Migitaka H, Iigo M, Itoh M, Yamamoto K, Ohtani-Kaneko R, Hara M, Suzuki T, Reiter R (1995). "Identification of melatonin in plants and its effects on plasma melatonin levels and binding to melatonin receptors in vertebrates". Biochem Mol Biol Int 35 (3): 627–34. PMID 7773197.

- ↑ Uz T, Arslan A, Kurtuncu M, Imbesi M, Akhisaroglu M, Dwivedi Y, Pandey G, Manev H (2005). "The regional and cellular expression profile of the melatonin receptor MT1 in the central dopaminergic system". Brain Res Mol Brain Res 136 (1 – 2): 45 – 53. doi:. PMID 15893586.

- ↑ Lincoln G, Andersson H, Loudon A (2003). "Clock genes in calendar cells as the basis of annual timekeeping in mammals — a unifying hypothesis". J Endocrinol 179 (1): 1 – 13. doi:. PMID 14529560.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Arendt J, Skene DJ (2005). "Melatonin as a chronobiotic". Sleep Med Rev 9 (1): 25–39. PMID 15649736. "Exogenous melatonin has acute sleepiness-inducing and temperature-lowering effects during 'biological daytime', and when suitably timed (it is most effective around dusk and dawn) it will shift the phase of the human circadian clock (sleep, endogenous melatonin, core body temperature, cortisol) to earlier (advance phase shift) or later (delay phase shift) times.".

- ↑ CM Chaturvedi (1984). "Effect of Melatonin on the Adrenl and Gonad of the Common Mynah Acridtheres tristis". Australian Journal of Zoology 32 (6): 803 – 809. doi:. http://www.publish.csiro.au/paper/ZO9840803.htm.

- ↑ Chen H (1981). "Spontaneous and melatonin-induced testicular regression in male golden hamsters: augmented sensitivity of the old male to melatonin inhibition". Neuroendocrinology 33 (1): 43–6. doi:. PMID 7254478.

- ↑ Filadelfi A, Castrucci A (1996). "Comparative aspects of the pineal/melatonin system of poikilothermic vertebrates". J Pineal Res 20 (4): 175–86. doi:. PMID 8836950.

- ↑ Sugden D, Davidson K, Hough K, Teh M (2004). "Melatonin, melatonin receptors and melanophores: a moving story" (HTML: full text). Pigment Cell Res 17 (5): 454–60. doi:. PMID 15357831. http://www.blackwell-synergy.com/doi/full/10.1111/j.1600-0749.2004.00185.x. Retrieved on 2008-05-03.

- ↑ Richardson G (2005). "The human circadian system in normal and disordered sleep". J Clin Psychiatry 66 Suppl 9: 3 – 9; quiz 42–3. PMID 16336035.

- ↑ Perreau-Lenz S, Pévet P, Buijs R, Kalsbeek A (2004). "The biological clock: the bodyguard of temporal homeostasis". Chronobiol Int 21 (1): 1 – 25. doi:. PMID 15129821.

- ↑ Brainard GC, Hanifin JP, Greeson JM, Byrne B, Glickman G, Gerner E, Rollag (August 15, 2001). "Action spectrum for melatonin regulation in humans: evidence for a novel circadian photoreceptor". J Neurosci. 15;21 (16): 6405–12. PMID 11487664.

- ↑ Kayumov L, Casper RF, Hawa RJ, Perelman B Chung SA, Sokalsky S, Shipiro (May 2005). "Blocking low-wavelength light prevents nocturnal melatonin suppression with no adverse effect on performance during simulated shift work". J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 90 (5): 2755–61. doi:. PMID 15713707.

- ↑ Navara, Kristen J.; Nelson, Randy J. (2007). "The dark side of light at night: physiological, epidemiological, and ecological consequences" (Review, PDF: full text). J. Pineal Res. 43 (43): 215–224. doi:. http://www.psy.ohio-state.edu/nelson/documents/JPinealRes2007.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-05-07.

- ↑ Schernhammer E, Rosner B, Willett W, Laden F, Colditz G, Hankinson S (2004). "Epidemiology of urinary melatonin in women and its relation to other hormones and night work". Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev 13 (62): 936–43. PMID 15184249.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Dun-Xian Tan, Lucien C. Manchester, Maria P. Terron, Luis J. Flores, Russel J. Reiter (2007). "One molecule, many derivatives: a never-ending interaction of melatonin with reactive oxygen and nitrogen species?". Journal of Pineal Research 42 (1): 28 – 42. doi:. PMID 17198536.

- ↑ Poeggeler B, Saarela S, Reiter RJ, et al (1994). "Melatonin--a highly potent endogenous radical scavenger and electron donor: new aspects of the oxidation chemistry of this indole accessed in vitro". Ann. N. Y. Acad. Sci. 738: 419–20. PMID 7832450.

- ↑ Tan D, Manchester L, Reiter R, Qi W, Karbownik M, Calvo J (2000). "Significance of melatonin in anti oxidative defense system: reactions and products". Biol Signals Recept 9 (3 – 4): 137–59. doi:. PMID 10899700.

- ↑ Karbownik M, Reiter R, Cabrera J, Garcia J (2001). "Comparison of the protective effect of melatonin with other antioxidants in the hamster kidney model of estradiol-induced DNA damage". Mutat Res 474 (1 – 2): 87 – 92. PMID 11239965.

- ↑ Tütüncüler F, Eskiocak S, Başaran UN, Ekuklu G, Ayvaz S, Vatansever U (2005). "The protective role of melatonin in experimental hypoxic brain damage". Pediatr Int 47 (4): 434–9. doi:. PMID 16091083.

- ↑ Ward Dean, John Morgenthaler, Steven William Fowkes (1993). Smart Drugs II: The Next Generation : New Drugs and Nutrients to Improve Your Memory and Increase Your Intelligence (Smart Drug Series, V. 2). Smart Publications. ISBN 0-9627418-7-6.

- ↑ Anisimov V, Alimova I, Baturin D, Popovich I, Zabezhinski M, Rosenfeld S, Manton K, Semenchenko A, Yashin A (2003). "Dose-dependent effect of melatonin on life span and spontaneous tumor incidence in female SHR mice". Exp Gerontol 38 (4): 449–61. doi:. PMID 12670632.

- ↑ Oaknin-Bendahan S, Anis Y, Nir I, Zisapel N (1995). "Effects of long-term administration of melatonin and a putative antagonist on the ageing rat". Neuroreport 6 (5): 785–8. doi:. PMID 7605949.

- ↑ Carrillo-Vico A, Guerrero J, Lardone P, Reiter R (2005). "A review of the multiple actions of melatonin on the immune system". Endocrine 27 (2): 189 – 200. doi:. PMID 16217132.

- ↑ Arushanian E, Beier E (2002). "Immunotropic properties of pineal melatonin". Eksp Klin Farmakol 65 (5): 73 – 80. PMID 12596522.

- ↑ Carrillo-Vico A, Reiter RJ, Lardone PJ, et al (2006). "The modulatory role of melatonin on immune responsiveness". Curr Opin Investig Drugs 7 (5): 423–31. PMID 16729718.

- ↑ Maestroni GJ (2001). "The immunotherapeutic potential of melatonin". Expert Opin Investig Drugs 10 (3): 467–76. doi:. PMID 11227046.

- ↑ Carrillo-Vico A, Lardone PJ, Fernández-Santos JM, et al (2005). "Human lymphocyte-synthesized melatonin is involved in the regulation of the interleukin-2/interleukin-2 receptor system". J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 90 (2): 992–1000. doi:. PMID 15562014.

- ↑ Cutolo M, Maestroni GJ (2005). "The melatonin-cytokine connection in rheumatoid arthritis". Ann. Rheum. Dis. 64 (8): 1109–11. doi:. PMID 16014678.

- ↑ 45.0 45.1 45.2 Lewis, Alan (1999). Melatonin and the Biological Clock. McGraw-Hill. pp. pp. 23. ISBN 0879837349.

- ↑ Sessa, Ben (2005). "Can psychedelics have a role in psychiatry once again?". The British Journal of Psychiatry 186: 457 – 458. doi:. PMID 15928353.

- ↑ Sessa, Ben (2005). "Endogenous psychoactive tryptamines reconsidered: an anxiolytic role for dimethyltryptamine". Med Hypotheses 5 (64): 930–7. PMID 15780487.

- ↑ Melke J, Botros HG, Chaste P et al. (2008). "Abnormal melatonin synthesis in autism spectrum disorders". Mol Psychiatry 13 (1): 90–8. doi:. PMID 17505466.

- ↑ Lewy A, Sack R, Miller L, Hoban T (1987). "Antidepressant and circadian phase-shifting effects of light". Science 235 (4786): 352–4. doi:. PMID 3798117.

- ↑ Uz T, Akhisaroglu M, Ahmed R, Manev H (2003). "The pineal gland is critical for circadian Period1 expression in the striatum and for circadian cocaine sensitization in mice". Neuropsychopharmacology 28 (12): 2117 – 23. doi:. PMID 12865893.

- ↑ Lee MY, Kuan YH, Chen HY, Chen TY, Chen ST, Huang CC, Yang IP, Hsu YS, Wu TS, Lee EJ. Intravenous administration of melatonin reduces the intracerebral cellular inflammatory response following transient focal cerebral ischemia in rats. J Pineal Res. 2007 Apr;42(3):297 – 309. PMID 17349029

- ↑ Dominguez-Rodriguez A, Abreu-Gonzalez P, Garcia-Gonzalez MJ, Kaski JC, Reiter RJ, Jimenez-Sosa A. A unicenter, randomized, double-blind, parallel-group, placebo-controlled study of Melatonin as an Adjunct in patients with acute myocardial infarction undergoing primary Angioplasty The Melatonin Adjunct in the acute myocardial infarction treated with Angioplasty (MARIA) trial: Study design and rationale. Contemp Clin Trials. 2006 Oct 17. PMID 17123867.

- ↑ Larson J, Jessen R, Uz T, Arslan A, Kurtuncu M, Imbesi M, Manev H (2006). "Impaired hippocampal long-term potentiation in melatonin MT2 receptor-deficient mice". Neurosci Lett 393 (1): 23–6. doi:. PMID 16203090.

- ↑ 54.0 54.1 Pappolla MA, Sos M, Omar RA, Bick RJ, Hickson-Bick DL, Reiter RJ, Efthimiopoulos S, Robakis NK. (1997). "Melatonin prevents death of neuroblastoma cells exposed to the Alzheimer amyloid peptide". J Neurosci 17 (5): 1683 – 1690. PMID 9030627.

- ↑ Wang X, Zhang J, Yu X, Han L, Zhou Z, Zhang Y, Wang J (2005). "Prevention of isoproterenol-induced tau hyperphosphorylation by melatonin in the rat". Sheng Li Xue Bao 57 (1): 7 – 12. PMID 15719129.

- ↑ Volicer L, Harper D, Manning B, Goldstein R, Satlin A (2001). "Sundowning and circadian rhythms in Alzheimer's disease". Am J Psychiatry 158 (5): 704–11. doi:. PMID 11329390.

- ↑ Tjon Pian Gi CV, Broeren JP, Starreveld JS, Versteegh FG (2003). "Melatonin for treatment of sleeping disorders in children with attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder: a preliminary open label study". Eur J Pediatr. 162 (7): 554 – 555. doi:. PMID 12783318.

- ↑ Bellipanni G, DI Marzo F, Blasi F, Di Marzo A (2005). "Effects of melatonin in perimenopausal and menopausal women: our personal experience". Ann N Y Acad Sci 1057 (Dec): 393 – 402. doi:. PMID 16399909.

- ↑ "Melatonin". About.com: Sleep Disorders: 4.

- ↑ Dodick D, Capobianco D (2001). "Treatment and management of cluster headache". Curr Pain Headache Rep 5 (1): 83 – 91. doi:. PMID 11252143.

- ↑ Gagnier J (2001). "The therapeutic potential of melatonin in migraines and other headache types". Altern Med Rev 6 (4): 383–9. PMID 11578254.

- ↑ Bhattacharjee, Yudhijit (14 September 2007). "Is Internal Timing Key to Mental Health?" (PDF). ScienceMag (AAAS) 317: 1488–90. http://www.ohsu.edu/ohsuedu/academic/som/images/Al-Lewy-Science.pdf. Retrieved on 2008-02-18.

- ↑ Maestroni G (1999). "Therapeutic potential of melatonin in immunodeficiency states, viral diseases, and cancer". Adv Exp Med Biol 467: 217–26. PMID 10721059.

- ↑ Barrenetxe J, Delagrange P, Martínez J (2004). "Physiological and metabolic functions of melatonin". J Physiol Biochem 60 (1): 61 – 72. PMID 15352385.

- ↑ Zhdanova I, Wurtman R, Regan M, Taylor J, Shi J, Leclair O (2001). "Melatonin treatment for age-related insomnia". J Clin Endocrinol Metab 86 (10): 4727 – 30. doi:. PMID 11600532.

- ↑ Lewy AJ, Emens JS, Sack RL, Hasler BP, Bernert RA (2002). "Low, but not high, doses of melatonin entrained a free-running blind person with a long circadian period". Chronobiol Int. 19 (3): 649–58. doi:. PMID 12069043.

- ↑ U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2007-06-22). "FDA Issues Dietary Supplements Final Rule". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-09-10.

- ↑ Buscemi, Nina; Ben Vandermeer, Nicola Hooton, Rena Pandya, Lisa Tjosvold, Lisa Hartling, Sunita Vohra, Terry P Klassen, Glen Baker (2006-02-18). "Efficacy and safety of exogenous melatonin for secondary sleep disorders and sleep disorders accompanying sleep restriction: meta-analysis" (HTML: Full text). BMJ 332 (7538): 385–393. doi:. PMID 16473858. http://www.bmj.com/cgi/content/full/332/7538/385. Retrieved on 2008-05-17.

- ↑ Buscemi, Nina; Ben Vandermeer, Nicola Hooton, Rena Pandya, Lisa Tjosvold, Lisa Hartling, Glen Baker, Terry P Klassen, Sunita Vohra (December 2005). "The Efficacy and Safety of Exogenous Melatonin for Primary Sleep Disorders: A Meta-Analysis" (HTML: Full text). J Gen Intern Med. (Society of General Internal Medicine) 20 (12): 1151–1158. doi:10.1111/j.1525-1497.2005.0243.x. (inactive 2008-06-29). PMID 16423108. http://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?tool=pubmed&pubmedid=16423108. Retrieved on 2008-05-17.

- ↑ "melatonin cautions". www.melatonin.com.

- ↑ Sack, Robert L.; Richard W. Brandes, Adam R. Kendall, Alfred J. Lewy (12 October 2000). "Entrainment of Free-Running Circadian Rhythms by Melatonin in Blind People". The NEW ENGLAND JOURNAL of MEDICINE 343 (15): 1070–1077. doi:. PMID 11027741. http://content.nejm.org/cgi/content/abstract/343/15/1070. Retrieved on 2008-04-13.

- ↑ Morera A, Henry M, de La Varga M (2001). "Safety in melatonin use". Actas Esp Psiquiatr 29 (5): 334–7. PMID 11602091.

- ↑ Terry PD, Villinger F, Bubenik GA, Sitaraman SV (2008). "Melatonin and ulcerative colitis: Evidence, biological mechanisms, and future research". Inflamm Bowel Dis. [Epub ahead of print]. PMID 18626968.

- ↑ Penn State College of Medicine, Milton S. Hershey Medical Center (September 2003). "Study Shows Melatonin Supplements May Make Standing A Hazard For The Cardiovascular-Challenged" (DOC). Press release. Retrieved on 2006-07-21. (MS Word Format)

- ↑ "Melatonin Information from Drugs.com".

External links

- ASSESSMENT REPORT FOR CIRCADIN by European Medicines Agency (PDF)

- SUMMARY OF PRODUCT CHARACTERISTICS FOR CIRCADIN by European Medicines Agency (PDF)

- Melatonin for jet lag?, Bandolier #82 (2000), reporting Spitzer et al (1999).

- Herxheimer A, Petrie KJ. Melatonin for the prevention and treatment of jet lag (Cochrane Review). In: The Cochrane Library, Issue 2, 2003.

- MedlinePlus DrugInfo natural-patient-melatonin

- Melatonin and aging (National Institute on Aging)

- A report on melatonin as sleep aid, March 2005 at MIT

- Melatonin clinical trials currently recruiting (National Institutes of Health)

|

||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||

|

|||||