Humpback Whale

| Humpback whale [1] | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

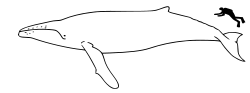

Size comparison against an average human

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||

| Binomial name | ||||||||||||||||||

| Megaptera novaeangliae Borowski, 1781 |

||||||||||||||||||

Humpback whale range

|

The humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae) is a Baleen whale. One of the larger rorqual species, adults range in length from 12–16 metres (40–50 ft) and weigh approximately 36,000 kilograms (79,000 lb). The humpback has a distinctive body shape, with unusually long pectoral fins and a knobbly head. It is an acrobatic animal, often breaching and slapping the water. Males produce a complex whale song, which lasts for 10 to 20 minutes and is repeated for hours at a time. The purpose of the song is not yet clear, although it appears to have a role in mating.

Found in oceans and seas around the world, humpback whales typically migrate up to 25,000 kilometres each year. Humpbacks feed only in summer, in polar waters, and migrate to tropical or sub-tropical waters to breed and give birth in the winter. During the winter, humpbacks fast and live off their fat reserves. The species' diet consists mostly of krill and small fish. Humpbacks have a diverse repertoire of feeding methods, including the bubble net feeding technique.

Like other large whales, the humpback was and is a target for the whaling industry. Due to over-hunting, its population fell by an estimated 90% before a whaling moratorium was introduced in 1966. Stocks of the species have since partially recovered; however, entanglement in fishing gear, collisions with ships, and noise pollution also remain concerns. There are at least 80,000 humpback whales worldwide. Once hunted to the brink of extinction, humpbacks are now sought out by whale-watchers, particularly off parts of Australia and the United States.

Contents |

Taxonomy

A phylogenetic tree of animals related to the humpback whale |

Humpback whales are rorquals (family Balaenopteridae), a family that includes the blue whale, the fin whale, the Bryde's whale, the Sei whale and the Minke whale. The rorquals are believed to have diverged from the other families of the suborder Mysticeti as long ago as the middle Miocene.[3] However, it is not known when the members of these families diverged from each other.

Though clearly related to the giant whales of the genus Balaenoptera, the humpback has been the sole member of its genus since Gray's work in 1846. More recently though, DNA sequencing analysis has indicated both the humpback and the Gray whale are close relatives of the Blue Whale, the world's largest animal. If further research confirms these relationships, it will be necessary to reclassify the rorquals.

The humpback whale was first identified as "baleine de la Nouvelle Angleterre" by Mathurin Jacques Brisson in his Regnum Animale of 1756. In 1781, Georg Heinrich Borowski described the species, converting Brisson's name to its Latin equivalent, Balaena novaeangliae. Early in the 19th century Lacépède shifted the humpback from the Balaenidae family, renaming it Balaenoptera jubartes. In 1846, John Edward Gray created the genus Megaptera, classifying the humpback as Megaptera longpinna, but in 1932, Remington Kellogg reverted the species names to use Borowski's novaeangliae.[4] The common name is derived from their humping motion when diving. The generic name Megaptera from the Greek mega-/μεγα- "giant" and ptera/πτερα "wing",[5] refers to their large front flippers. The specific name means "New Englander" and was probably given by Brisson due the regular sightings of humpbacks off the coast of New England.[4]

Description and lifecycle

Humpback whales can easily be identified by their stocky bodies with obvious humps and black dorsal colouring. The head and lower jaw are covered with knobs called tubercles, which are actually hair follicles and are characteristic of the species. The tail flukes, which are lifted high in some dive sequences, have wavy trailing edges.[6] There are four global populations, all being studied. North Pacific, Atlantic, and southern ocean humpbacks have distinct populations which make an annual migration. One population in the Indian Ocean does not migrate. The Indian Ocean has a northern coastline, while the Atlantic and Pacific oceans do not, thereby preventing the humpbacks from migrating to the pole.

The long black and white tail fin, which can be up to a third of body length, and the pectoral fins have unique patterns, which enable individual whales to be recognised.[7][8] Several suggestions have been made to explain the evolution of the humpback's pectoral fins, which are proportionally the longest fins of any cetacean. The two most enduring hypotheses are the higher maneuverability afforded by long fins, or that the increased surface area is useful for temperature control when migrating between warm and cold climates. Humpbacks also have 'rete mirable' a heat exchanging system, which works similarly to the same structured system in certain species of sharks and other fish.

Humpbacks have 270 to 400 darkly coloured baleen plates on each side of the mouth. The plates measure from a mere 18 inches (460 mm) in the front to approximately 3 feet (0.91 m) long in the back, behind the hinge. Ventral grooves run from the lower jaw to the umbilicus about halfway along the bottom of the whale. These grooves are less numerous (usually 16–20) and consequently more prominent than in other rorquals. The stubby dorsal fin is visible soon after the blow when the whale surfaces, but has disappeared by the time the flukes emerge. Humpbacks have a distinctive 3 m (10 ft) heart shaped to bushy blow, or exhalation of water through the blowholes. Early whalers also noted blows from humpback adults to be 10 - 20 feet (6.1 m) high. Whaling records show they understood each specie has its own distinct shape and height of blows.

Newborn calves are roughly the length of their mother's head. A 50-foot (15 m) mother would have a 20-foot (6.1 m) newborn weighing in at 2 short tons (1.8 MT). They are nursed by their mothers for approximately six months, then are sustained through a mixture of nursing and independent feeding for possibly six months more. Humpback milk is 50% fat and pink in color. Some calves have been observed alone after arrival in Alaskan waters. Females reach sexual maturity at the age of five with full adult size being achieved a little later. According to new research, males reach sexual maturity at approximately 7 years of age. Fully grown the males average 15–16 m (49–52 ft), the females being slightly larger at 16–17 m (52–56 ft), with a weight of 40,000 kg (or 44 tons); the largest recorded specimen was 19 m (62 ft) long and had pectoral fins measuring 6 m (20 ft) each.[9] The largest humpback on record, according to whaling records, was killed in the Caribbean. She was 88 feet (27 m) long, weighing nearly 90 tons.

Females have a hemispherical lobe about 15 centimetres (6 in) in diameter in their genital region. This allows males and females to be distinguished if the underside of the whale can be seen, even though the male's penis usually remains unseen in the genital slit. Male whales have distinctive scars on heads and bodies, some resulting from battles over females.

Females typically breed every two or three years. The gestation period is 11.5 months, yet some individuals can breed in two consecutive years. Humpback whales were thought to live 50–60 years, but new studies using the changes in amino acids behind eye lenses proved another baleen whale, the Bowhead, to be 211 years old. This was an animal taken by the Inuit off Alaska. More studies on ages are currently being done.

Identification

The varying patterns on the humpback's tail flukes are sufficient to identify an individual. Unique visual identification is not possible in most cetacean species (exceptions include Orcas and Right Whales), so the humpback has become one of the most-studied species. A study using data from 1973 to 1998 on whales in the North Atlantic gave researchers detailed information on gestation times, growth rates, and calving periods, as well as allowing more accurate population predictions by simulating the mark-release-recapture technique. A photographic catalogue of all known whales in the North Atlantic was developed over this period and is currently maintained by Wheelock College.[10] Similar photographic identification projects have subsequently begun in the North Pacific by SPLASH (Structure of Populations, Levels of Abundance and Status of Humpbacks), and around the world. Another organization (Cascadia Research) headed by well known researcher John Calambokidis, along with Dr. Robin Baird, have joined with others from NOAA, hoping to soon have an online catalog of more than 3500 fluke identification pictures that the public can access, and possibly contribute to.

Social structure and courtship

- See also: Whale surfacing behaviour

The humpback social structure is loose-knit. Usually, individuals live alone or in small transient groups that assemble and break up over the course of a few hours. Groups may stay together a little longer in summer in order to forage and feed cooperatively. Longer-term relationships between pairs or small groups, lasting months or even years, have been observed, but are rare. Recent studies extrapolate feeding bonds observed with many females in Alaskan waters over the last 10 years. It is possible some females may have these bonds for a lifetime. More studies need to be done on this. The range of the humpback overlaps considerably with many other whale and dolphin species — while it may be seen near other species (for instance, the Minke Whale), it rarely interacts socially with them. Humpback calves have been observed in Hawaiian waters playing with bottlenose dolphin calves.

Courtship rituals take place during the winter months, when the whales migrate toward the equator from their summer feeding grounds closer to the poles. Competition for a mate is usually fierce, and female whales as well as mother-calf dyads are frequently trailed by unrelated male whales dubbed escorts by researcher Louis Herman. Groups of two to twenty males typically gather around a single female and exhibit a variety of behaviours in order to establish dominance in what is known as a competitive group. The displays may last several hours, the group size may ebb and flow as unsuccessful males retreat and others arrive to try their luck. Techniques used include breaching, spy-hopping, lob-tailing, tail-slapping, flipper-slapping, charging and parrying. "Super pods" have been observed numbering more than 40 males, all vying for the same female. (M. Ferrari et al)

Whale song is assumed to have an important role in mate selection; however, scientists remain unsure whether the song is used between males in order to establish identity and dominance, between a male and a female as a mating call, or a mixture of the two. All these vocal and physical techniques have also been observed while not in the presence of potential mates. This indicates that they are probably important as a more general communication tool. Recent studies showed singing males attract other males. Scientists are extrapolating possibilities the singing may be a way to keep the migrating populations connected. (Ferrari, Nicklin, Darling, et al.) It has also been noted that the singing begins when the competition ends. Studies on this are ongoing. (www.whaletrust.com)

Feeding

The species feeds only in summer and lives off fat reserves during winter. Humpback whales will only feed rarely and opportunistically while in their wintering waters. It is an energetic feeder, taking krill and small schooling fish, such as herring (Clupea harengus), salmon, capelin (Mallotus villosus) and sand lance (Ammodytes americanus) as well as Mackerel (Scomber scombrus), pollock (Pollachius virens) and haddock (Melanogrammus aeglefinus) in the North Atlantic.[11][12][13] Krill and Copepods have been recorded from Australian and Antarctic waters.[14] It hunts fish by direct attack or by stunning them by hitting the water with its pectoral fins or flukes.

The humpback has the most diverse repertoire of feeding methods of all baleen whales.[15] Its most inventive technique is known as bubble net feeding: a group of whales blows bubbles while swimming in circles to create a ring of bubbles. The ring encircles the fish, which are confined in an ever-tighter area as the whales swim in a smaller and smaller circles. The whales then suddenly swim upward through the bubble net, mouths agape, swallowing thousands of fish in one gulp. This technique can involve a ring of bubbles up to 30 m (100 ft) in diameter and the cooperation of a dozen animals. Some of the whales take the task of blowing the bubbles through their blowholes, some dive deeper to drive fish toward the surface, and others herd fish into the net by vocalizing.[16] Humpbacks have been observed bubblenet feeding alone as well.

Humpback whales are preyed upon by Orcas. The result of these attacks is generally nothing more serious than some scarring of the skin, but it is likely that young calves are sometimes killed.[17]

Song

Both male and female humpback whales can produce sounds, however only the males produce the long, loud, complex "songs" for which the species is famous. Each song consists of several sounds in a low register that vary in amplitude and frequency, and typically lasts from 10 to 20 minutes.[18] Songs may be repeated continuously for several hours; humpback whales have been observed to sing continuously for more than 24 hours at a time. As cetaceans have no vocal cords, whales generate their song by forcing air through their massive nasal cavities.

Whales within an area sing the same song, for example all of the humpback whales of the North Atlantic sing the same song, and those of the North Pacific sing a different song. Each population's song changes slowly over a period of years —never returning to the same sequence of notes.[18]

Scientists are still unsure of the purpose of whale song. Only male humpbacks sing, so it was initially assumed that the purpose of the songs was to attract females. However, many of the whales observed to approach singing whales have been other males, with the meeting resulting in a conflict. Thus, one interpretation is that the whale songs serve as a threat to other males.[19] Some scientists have hypothesized that the song may serve an echolocative function.[20] During the feeding season, humpback whales make altogether different vocalizations, which they use to herd fish into their bubble nets.[21]

Population and distribution

The humpback whale is found in all the major oceans, in a wide band running from the Antarctic ice edge to 65° N latitude, though is not found in the eastern Mediterranean or the Baltic Sea. There are at least 80,000 humpback whales worldwide, with 18,000-20,000 in the North Pacific, about 12,000 in the North Atlantic, and over 50,000 in the Southern Hemisphere, down from a pre-whaling population of 125,000.[6]

The humpback is a migratory species, spending its summers in cooler, high-latitude waters, but mating and calving in tropical and sub-tropical waters.[18] An exception to this rule is a population in the Arabian Sea, which remains in these tropical waters year-round.[18] Annual migrations of up to 25,000 kilometres (16,000 statute miles) are typical, making it one of the farthest-travelling of any mammalian species.

A 2007 study identified seven individual whales wintering off the Pacific coast of Costa Rica as those which had made a trip from the Antarctic of around 8,300 km. Identified by their unique tail patterns, these animals have made the longest documented migration by a mammal.[22]

In Australia, two main migratory populations have been identified, off the west and east coast respectively. These two populations are distinct with only a few females in each generation crossing between the two groups.[23]

Whaling

- See also: Whaling in Japan

One of the first attempts to hunt the humpback whale was made by John Smith in 1614 off the coast of Maine. Opportunistic killing of the species is likely to have occurred long before, and it continued with increasing pace in the following centuries. By the 18th century, the commercial value of humpback whales had been recognized, and they became a common target for whalers for many years.

By the 19th century, many nations (the United States in particular), were hunting the animal heavily in the Atlantic Ocean, and to a lesser extent in the Indian and Pacific Oceans. It was, however, the introduction of the explosive harpoon in the late 19th century that allowed whalers to accelerate their take. This, along with hunting beginning in the Antarctic Ocean in 1904, led to a sharp decline in most whale populations.

It is estimated that during the 20th century at least 200,000 humpbacks were taken, reducing the global population by over 90%, with the population in the North Atlantic estimated to have dropped to as low as 700 individuals.[24]

To prevent extinction, the International Whaling Commission introduced a ban on commercial humpback whaling in 1966. That ban is still in force. By that time humpback whales were so scarce that commercial hunting was no longer worthwhile.

At this time, 250,000 were recorded killed. However, the true toll is likely to be higher. It is now known that the Soviet Union was deliberately under-recording its kills; the total Soviet humpback kill was reported at 2,820 whereas the true number is now believed to be over 48,000.[25]

As of 2004, hunting of humpback whales is restricted to a few animals each year off the Caribbean island Bequia in the nation of St. Vincent and the Grenadines.[15] The take is not believed to threaten the local population.

Japan had planned to kill 50 humpback whales in the 2007/08 season under its JARPA II research program in the Antarctic Ocean, starting in November 2007. The announcement sparked global protests.[26] After a visit to Tokyo by the chairman of the IWC, asking the Japanese for their co-operation in sorting out the differences between pro- and anti-whaling nations on the Commission, the Japanese whaling fleet agreed that no humpback whales would be caught for the two years it would take for the IWC to reach a formal agreement.[27]

Conservation

Internationally this species is considered vulnerable. Most monitored stocks of humpback whales have rebounded well since the end of the commercial whaling era,[2][28] such as the North Atlantic where stocks are now believed to be approaching pre-hunting levels. However, the species is considered endangered in some countries where local populations have recovered slowly, including the United States.[29]

Today, individuals are vulnerable to collisions with ships, entanglement in fishing gear, and noise pollution.[2] Like other cetaceans, humpbacks are sensitive to noise and can even be injured by it. In the 19th century, two humpback whales were found dead near sites of repeated oceanic sub-bottom blasting, with traumatic injuries and fractures in the ears.[30]

Once hunted to the brink of extinction the humpback whale has made a dramatic comeback in the North Pacific Ocean. A study released May 22, 2008 estimates that the humpback whale population that hit a low of 1,500 whales before hunting was banned worldwide, has made a comeback to a population of between 18,000 and 20,000.[31]

The ingestion of saxitoxin, a Paralytic shellfish poisoning (PSP) from contaminated mackerel has been implicated in humpback whale deaths.[32]

Some countries are creating action plans to protect the humpback; for example, in the United Kingdom, the humpback whale has been designated as a priority species under the national Biodiversity Action Plan, generating a set of actions to conserve the species. The sanctuary provided by National Parks such as Glacier Bay National Park and Preserve and Cape Hatteras National Seashore, among others, have also become a major factor in sustaining the populations of the species in those areas.[33]

Although much was known about the humpback whale due to information obtained through whaling, the migratory patterns and social interactions of the species were not well known until two separate studies by R. Chittleborough and W. H. Dawbin in the 1960s.[34] Roger Payne and Scott McVay made further studies of the species in 1971.[35] Their analysis of whale song led to worldwide media interest in the species, and left an impression in the public mind that whales were a highly intelligent cetacean species, a contributing factor to the anti-whaling stance of many countries.

In August 2008, the IUCN changed the whale's status from Vulnerable to Least Concern, although two subpopulations remain endangered.[36]

Whale-watching

Humpback whales are generally curious about objects in their environment. Some individuals, referred to as "friendlies", will approach whale-watching boats very closely, often staying under or near the boat for many minutes. Because humpbacks are often easily approachable, curious, easily identifiable as individuals, and display many behaviors, they have become the mainstay of whale-watching tourism in many locations around the world since the 1980s.

There are many commercial whale-watching operations on both the humpback's summer and winter ranges:

| North Atlantic | North Pacific | Southern Hemisphere | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Summer | New England, Nova Scotia and Newfoundland, the northern St. Lawrence River, the Snaefellsnes peninsula in the west of Iceland | central California, Alaska, Oregon, Washington, Vancouver | Antarctica |

| Winter | Samaná Province of the Dominican Republic, the Bay of Biscay France, | Hawaii, Baja, the Bahía de Banderas off Puerto Vallarta | Sydney, Byron Bay north of Sydney, Hervey Bay north of Brisbane, North and East of Cape Town, New Zealand, the Tongan islands, |

As with other cetacean species, however, a mother whale will generally be extremely protective of her infant, and will seek to place herself between any boat and the calf before moving quickly away from the vessel. Whale-watching tour operators are asked to avoid stressing the mother.

Famous humpbacks

Migaloo

A presumably albino humpback whale that travels up and down the east coast of Australia has become famous in the local media, on account of its extremely rare all-white appearance. The whale, first sighted in 1991 and believed to be 3-5 years old at that time, is called Migaloo (a word for "white fellow" from one of the languages of the Indigenous Australians). Speculation about the whale's gender was resolved in October 2004 when researchers from Southern Cross University collected sloughed skin samples from Migaloo as he migrated past Lennox Head, and subsequent genetic analysis of the samples proved he is a male. Because of the intense interest, environmentalists feared that the whale was becoming distressed by the number of boats following it each day. In response, the Queensland and New South Wales governments introduce legislation each year to order the maintenance of a 500 m (1,600 ft) exclusion zone around the whale. Recent close up pictures have shown Migaloo to have skin cancer and/or skin cysts as a result of his lack of protection from the sun.[37]

In 2006, a white calf was spotted with a normal humpback mother in Byron Bay, New South Wales.[38]

Humphrey

One of the most notable humpback whales is Humphrey the whale, who was rescued twice in California by The Marine Mammal Center and other concerned groups.[39][40] The first rescue was in 1985, when he swam into San Francisco Bay and then up the Sacramento River towards Rio Vista.[41] Five years later, Humphrey returned and became stuck on a mudflat in San Francisco Bay immediately north of Sierra Point below the view of onlookers from the upper floors of the Dakin Building. He was pulled off the mudflat with a large cargo net and the help of a Coast Guard boat. Both times he was successfully guided back to the Pacific Ocean using a "sound net" in which people in a flotilla of boats made unpleasant noises behind the whale by banging on steel pipes, a Japanese fishing technique known as "oikami." At the same time, the attractive sounds of humpback whales preparing to feed were broadcast from a boat headed towards the open ocean.[42] Since leaving the San Francisco Bay in 1990 Humphrey has been seen only once, at the Farallon Islands in 1991.

Delta and Dawn

A humpback whale mother and calf captivated the San Francisco Bay Area in May 2007.[43] This pair appeared to have gotten lost on their Northern migration, swam into the bay and up the Sacramento River as far as the Port of Sacramento. First spotted on 13 May, the whales inspired intense news coverage and were named Delta and Dawn. Whale fans became worried as the whales, both injured with what were possibly cuts caused by boat propellers, continued their stay in the brackish waters, despite efforts to get them to return to the sea. Unexpectedly, on 20 May they headed back towards the bay, but they tarried near the Rio Vista bridge for 10 days. Finally, on Memorial Day weekend, they left Rio Vista, California; passing Tuesday night, 29 May, through the Golden Gate Bridge out to the Pacific Ocean.

Mister Splashy Pants

Mister Splashy Pants is a humpback in the south Pacific Ocean. It's being tracked with a satellite tag by Greenpeace as a part of its Great Whale Trail Expedition.[44] The whale's name was chosen in an online poll that garnered attention from several websites, including Boing Boing and Reddit.[45] The name "Mister Splashy Pants" received over 78% of the votes.[46]

Colin

Colin was the name given to a presumably abandoned starving humpback calf that was discovered in August 2008 at Pittwater, north of Sydney, Australia. It attempted to suckle from moored boats to obtain food.[47][48] Despite attempts to reunite the calf with whale pods by luring it out to sea, it returned to Pittwater. Opinion was divided on how best to handle the situation, with some advocating feeding artificial milk formula to the calf, and others advocating euthanasia.[49]

Colin was euthanised on 22 August 2008 due to his deteriorating condition.[50]

The calf's plight gained media attention as far afield as the United States, [51] United Kingdom, [52] Italy, [53] Netherlands, [54] Russia, [55] Canada [56] and New Zealand. [57]

A subsequent autopsy found that Colin was terminally ill with an emaciated pancreas, ulcers of the stomach and oesophagus, intestinal erosion and infected shark bites.[58] The calf was estimated to be only 7-10 days old and must have been separated from its mother shortly after birth.[59]

Media

- See also: List of whale songs

Footnotes

- ↑ Mead, James G. and Robert L. Brownell, Jr (November 16 2005). Wilson, D. E., and Reeder, D. M. (eds). ed.. Mammal Species of the World (3rd edition ed.). Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 723–743. ISBN 0-801-88221-4. http://www.bucknell.edu/msw3/browse.asp?id=14300027.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Reilly, S.B., Bannister, J.L., Best, P.B., Brown, M., Brownell Jr., R.L., Butterworth, D.S., Clapham, P.J., Cooke, J., Donovan, G.P., Urbán, J. & Zerbini, A.N. (2008). Megaptera novaeangliae. 2008 IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. IUCN 2008. Retrieved on 7 October 2008.

- ↑ Gingerich P (2004). "Whale Evolution". McGraw-Hill Yearbook of Science & Technology. The McGraw Hill Companies.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Martin S (2002). The Whales' Journey. Allen & Unwin Pty., Limited. pp. 251. ISBN 1865082325.

- ↑ Liddell & Scott (1980). Greek-English Lexicon, Abridged Edition. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK. ISBN 0-19-910207-4.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 (PDF)Recovery Plan for the Humpback Whale (Megapten Novaeangliae), National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, 1991, http://www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/pdfs/recovery/whale_humpback.pdf

- ↑ Katona S.K. and Whitehead, H.P. (1981). "Identifying humpback whales using their mural markings". Polar Record (20): 439–444.

- ↑ Kaufman G., Smultea M.A. and Forestell P. (1987). "Use of lateral body pigmentation patterns for photo ID of east Australian (Area V) humpback whales". Cetus 7 (1): 5–13.

- ↑ Clapham P. "Humpback Whale". Encyclopedia of Marine Mammals. pp. 589–592. ISBN 0125513402.

- ↑ Williamson JM (2005). "Whalenet Data Search". Wheelock College. Retrieved on 2007-04-03.

- ↑ Overholtz W.J. and Nicholas J.R. (1979). "Apparent feeding by the fin whale, Balaenoptera physalus, and humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, on the American sand lance, Ammodytes americanus, in the Northwest Atlantic". Fish. Bull. (77): 285–287.

- ↑ Whitehead H. (1987). "Updated status of the humpback whale, Megaptera novaeangliae, in Canada". Canadian Field-Naturalist 101 (2): 284–294.

- ↑ Meyer T.L., Cooper R.A. and Langton R.W. (1979). "Relative abundance, behavior and food habits of the American sand lance (Ammodytes americanus) from the Gulf of Maine". Fish. Bull 77 (1): 243–253.

- ↑ Nemoto T. (1959). "Food of baleen whales with reference to whale movements". Science Report Whales Research Institute Tokyo (14): 149–290.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 Prepared by the Humpback Whale Recovery Team for the National Marine Fisheries Service, Silver Spring, Maryland (1991). Recovery Plan for the Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)'. National Marine Fisheries Service. pp. 105.

- ↑ Acklin, Deb (2005-08-05). "Crittercam Reveals Secrets of the Marine World", National Geographic News. Retrieved on 2007-11-01.

- ↑ Clapham, P.J. (1996). "The social and reproductive biology of humpback whales: an ecological perspective" (PDF). Mammal New studies (Ferrari, Mizroch, et.al.) show first year calf mortality is 18-20%. Beyond the first year is still being studied. Review (26): 27–49. http://www.sitkawhalefest.org/review.pdf. Retrieved on 2007-04-26.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 18.3 "American Cetacean Society Fact Sheet". American Cetacean Society. Retrieved on 2007-04-17.

- ↑ "Humpback Whales. Song of the Sea.". Public Broadcasting Station. Retrieved on 2007-04-22.

- ↑ Mercado E III & Frazer LN (July 2001). "Humpback Whale Song or Humpback Whale Sonar? A Reply to Au et al." (PDF). IEEE Journal of Oceanic Engineering 26 (3): 406–415. doi:. http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~emiii/00946514.pdf.

- ↑ Mercado E III, Herman LM & Pack AA (2003). "Stereotypical sound patterns in humpback whale songs: Usage and function" (PDF). Aquatic Mammals 29 (1): 37–52. doi:. http://www.acsu.buffalo.edu/~emiii/mercado_et_al_03.pdf.

- ↑ Rasmussen K, Palacios DM, Calambokidis J, Saborío MT, Dalla Rosa L, Secchi ER, Steiger GH, Allen JM, & Stone GS (2007). "Southern Hemisphere humpback whales wintering off Central America: insights from water temperature into the longest mammalian migration". Biology Letters 3 (10.1098/rsbl.2007.0067): 302. doi:. ISSN 1744-957X. http://www.journals.royalsoc.ac.uk/openurl.asp?genre=article&doi=10.1098/rsbl.2007.0067.

- ↑ "Megaptera novaeangliae in Species Profile and Threats Database". Australian Government: Department of the Environment and Water Resources (2007). Retrieved on 2007-04-17.

- ↑ Breiwick JM, Mitchell E, Reeves RR (1983) Simulated population trajectories for northwest Atlantic humpback whales 1865–1980. Fifth biennial Conference on Biology of Marine Mammals, Boston Abstract. p14

- ↑ Prof. Alexey V. Yablokov (1997). "On the Soviet Whaling Falsification, 1947–1972". Whales Alive! (Cetacean Society International) 6 (4). http://csiwhalesalive.org/csi97403.html.

- ↑ scoop.co.nz: Leave Humpback Whales Alone Message To Japan 16 May 2007

- ↑ BBC NEWS | World | Asia-Pacific | Japan changes track on whaling

- ↑ "Study: Humpback whale population is rising" (2008-05-23). Retrieved on 2008-05-23.

- ↑ "Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)". Division of Wildlife Conservation, Alaska Department of Fish and Game (2006). Retrieved on 2008-02-10.

- ↑ "Blast injury in humpback whale ears". Journal of the Acoustic Society of America (94). 1849–1850.

- ↑ Study: N. Pacific humpback whale population rises - Yahoo! News

- ↑ Dierauf L & Gulland F (2001). Marine Mammal Medicine. CRC Press. ISBN 0849308399.

- ↑ "Humpback Whale (Megaptera novaeangliae)". National Parks Conservation Association. Retrieved on 2007-04-19.

- ↑ Chittleborough RG. (1965) Dynamics of two populations of the humpback whale. Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research 16: 33–128.

- ↑ Payne RS, McVay S. (1971) Songs of humpback whales. Science 173:585–597.

- ↑ "Humpback whale on road to recovery, reveals IUCN Red List". IUCN (2008-08-12). Retrieved on 2008-08-12.

- ↑ "Migaloo, the White Humpback Whale". Pacific Whale Foundation (2004). Retrieved on 2007-04-03.

- ↑ (BBC News, Sydney) " New white whale spotted", 22 July 2008.

- ↑ Tokuda W (1992) Humphrey the lost whale, Heian Intl Publishing Company. ISBN 0-89346-346-9

- ↑ Callenbach E & Leefeldt C Humphrey the Wayward Whale, ISBN 0-930588-23-1

- ↑ Jane Kay, San Francisco Examiner Monday, 9 October 1995

- ↑ Toni Knapp, The Six Bridges of Humphrey the Whale. Illustrated by Craig Brown. Roberts Rinehart, 1993 (1989)

- ↑ Lee, Henry & Martin, Glen, San Francisco Chronicle, "Whales disappear -- rescuers believe they're back at sea", 2007-03-30,http://sfgate.com/cgi-bin/article.cgi?f=/c/a/2007/05/30/BAG9EQ3TU818.DTL

- ↑ Timothy Marshall (2007-11-29). "Whale name makes a big splash". Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

- ↑ AbiSilvester (2007-11-29). "'Mister Splashy Pants' emerges as clear favourite in Greenpeace whale-naming competition". Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "Mister Splashy Pants the whale - you named him, now save him" (2007-12-10). Retrieved on 2007-12-10.

- ↑ "Prognosis 'grim' for abandoned baby whale". The Australian (2008-08-20). Retrieved on 2008-08-20.

- ↑ "No baby whale feeding solution after expert talks". Australian Broadcasting Corporation (2008-08-20). Retrieved on 2008-08-20.

- ↑ "BBC NEWS Asia-Pacific Hopes fade for Sydney whale calf". BBC (2008-08-20). Retrieved on 2008-08-20.

- ↑ "Colins time runs out". Sydney Morning Herald (2008-08-22). Retrieved on 2008-08-22.

- ↑ Thomas, Pete (2008-08-22). "Colin the humpback whale put to sleep", The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ "Australians mourn baby whale 'Colin'", The Independent (2008-08-22). Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ "Australia: Euthanasia Ends Sad Tale of Orphaned Whale Cub", AGI (2008-08-22). Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ "Conservationists put down baby whale", Radio Netherlands (2008-08-22). Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ "Abandoned baby whale euthanized in Australia", RIA Novosti (2008-08-22). Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ "Dying whale calf euthanized", Times Colonist (2008-08-22). Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ "Whale's euthanasia defended", The New Zealand Herald (2008-08-23). Retrieved on 2008-08-23.

- ↑ "Abandoned whale calf was 'terminally ill'", ABC News (2008-10-17).

- ↑ "Euthanased whale calf had fatal illnesses", Sydney Morning Herald (2008-10-17).

References

Books

- Clapham, Phil. (1996). Humpback Whales. ISBN 0-948661-87-9

- Clapham, Phil. Humpback Whale. pp 589–592 in the Encyclopeadia of Marine Mammals. ISBN 0-12-551340-2

- Reeves, Stewart, Clapham and Powell. Date? National Audubon Society Guide to Marine Mammals of the World. ISBN 0-375-41141-0

- Dawbin, W. H. The seasonal migratory cycle of humpback whales. In K.S. Norris (ed), Whales, Dolphins and Porpoises. University of California Press.

Journal articles

- Best, P. B. (1993) Increase rates in severely depleted stocks of baleen whales. ICES Journal of Marine Science 50:169–186.

- Smith, T.D.; J. Allen, P.J. Clapham, P.S. Hammond, S. Katona, F. Larsen, J. Lien, D. Mattila, P.J. Palsboll, J. Sigurjonsson, P.T. Stevick & N. Oien. (1999) An ocean-basin-wide mark-recapture study of the North Atlantic humpback whale. Marine Mammal Science 15: 1–32.

External links

- General

- ARKive - images and movies of the humpback whale (Megaptera novaeangliae).

- Photos and information about humpback whales and other cetaceans in Mayumba National Park

- Humpbacks of Hervey Bay, Queensland, Australia

- The Dolphin Institute Whale Resource Guide and scientific publications

- Humpback Whale Gallery (Silverbanks)

- (French)Humpback whale videos

- Book about the two humpback whales lost in the Sacramento River in May 2007 -

- The Humpback Whales of Hervey Bay

- Humpback whale songs

- A detailed analysis of the form and function of the humpback whale song, from the University at Buffalo

- The Whalesong Project

- Article from PHYSORG.com on the complex syntax of whalesong phrases

- Conservation

- Estimating the humpback population in the Pacific, from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration

- Estimating the humpback population in the Atlantic, from Dalhousie University

- Recovery plan in Australia: 2005–2010

- Humpback Whales in the Sacramento River by the NOAA

- The Oceania Project, Humpback Whale Research, Hervey Bay

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||