Mastodon

| Mastodon Fossil range: 4–0 Ma Pliocene – Recent |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

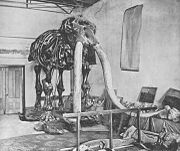

Mounted mastodon skeleton, Museum of the Earth .

|

||||||||||||

| Conservation status | ||||||||||||

|

Prehistoric

|

||||||||||||

| Scientific classification | ||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||

| Species | ||||||||||||

|

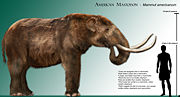

Mastodons or Mastodonts (from Greek μαστός and οδούς, meaning "nipple tooth") are members of the extinct genus Mammut of the order Proboscidea and form the family Mammutidae; they resembled, but were distinct from, the woolly mammoth, which belongs to the family Elephantidae. Mastodons were browsers, while mammoths were grazers.

Contents |

Habitat

Mastodons are thought to have first appeared almost four million years ago. They were native to both Eurasia and North America but the Eurasian species Mammut borsoni died out approximately three million years ago - fossils having been found in England, Germany, the Netherlands, Romania[1] and northern Greece. Mammut americanum is generally reported as having disappeared from North America about 10,000 years ago,[2] at the same time as most other Pleistocene megafauna. However more recent radiocarbon dates have been found, such as 5,200 B.C. in Seneca Michigan,[3] 5,140 B.C. in Utah,[4] 4,150 in Washtenaw Michigan,[5] 4,080 B.C. in Lapeer Michigan,[6]. It is known from fossils found ranging from present-day Alaska and New England in the north, to Florida, southern California, Mexico, and as far south as Honduras.[7]

Though their habitat spanned a large territory, mastodons were most common in the ice age spruce forests of the eastern United States, as well as in warmer lowland environments.[8] Their remains have been found as far as 300 kilometers offshore of the northeastern United States, in areas that were dry land during the low sea level stand of the last ice age.[9] Mastodon fossils have been found on the Olympic Peninsula of Washington State, USA (Manis Mastodon Site),[10] in Kentucky (particularly noteworthy are early finds in what is now Big Bone Lick State Park); the Kimmswick Bone Bed in Missouri; in Stewiacke, Nova Scotia, Canada; at a number of sites in New York State[11];in Richland County, Wisconsin; La Grange, Texas; Southern Louisiana; north of Fort Wayne, Indiana; and Johnstown, Ohio[12] USA.

Description

While mastodons were furry like woolly mammoths and similar in height at roughly three meters at the shoulder, the resemblance was superficial. They differed from mammoths primarily in the blunt, conical, nipple-like projections on the crowns of their molars,[13] which were more suited to chewing leaves than the high-crowned teeth mammoths used for grazing; the name mastodon (or mastodont) means "nipple teeth" and is also an obsolete name for their genus.[14] Their skulls were larger and flatter than those of mammoths, while their skeleton was stockier and more robust.[15] Mastodons also seem to have lacked the undercoat characteristic of mammoths.[15]

The tusks of the mastodon sometimes exceeded five meters in length and were nearly horizontal, in contrast with the more curved mammoth tusks.[15] Young males had vestigial lower tusks that were lost in adulthood.[15] However, it has been proven that female mastodons had lower pairs of tusks. The tusks were probably used to break branches and twigs, although some evidence suggests males may have used them in mating challenges; one tusk is often shorter than the other, suggesting that, like humans and modern elephants, mastodons may have had laterality.[15] Examination of fossilized tusks revealed a series of regularly spaced shallow pits on the underside of the tusks. Microscopic examination showed damage to the dentin under the pits. It is theorized that the damage was caused when the males were fighting over mating rights. The curved shape of the tusks would have forced them downward with each blow, causing damage to the newly forming ivory at the base of the tusk. The regularity of the damage in the growth patterns of the tusks indicates that this was an annual occurrence, probably occurring during the spring and early summer.[16]

Extinction

Recent studies indicate that tuberculosis may have been partly responsible for the extinction of the mastodon 10,000 years ago.[17]

Another influencing factor to their eventual extinction in America during the late Pleistocene may have been the presence of Paleo-Indians, who entered the American continent in relatively large numbers 13,000 years ago. Their hunting caused a gradual attrition to the mastodon and mammoth populations, significant enough that over time the mastodons were hunted to extinction.[18]

In September 2007, Mark Holley, an underwater archeologist with the Grand Traverse Bay Underwater Preserve Council who teaches at Northwestern Michigan College in Traverse City, Michigan, said that they might have discovered a boulder (3.5 to 4 feet (1.2 m) high x 5 feet (1.5 m) long) with a prehistoric carving in the Grand Traverse Bay of Lake Michigan. The granite rock has markings that resemble a mastodon with a spear in its side. Confirmation that the markings are an ancient petroglyph will require more evidence.[19]

Current excavations

Current excavations are going on annually at the Hiscock site in Byron, New York, for mastodon and related paleo-Indian artifacts. The site was discovered in 1959 by the Hiscock family while digging a pond with a backhoe; they found a large tusk and stopped digging. The Buffalo Museum of Science has organized the dig since 1983. It has been called one of the richest sites available for mastodon-related artifacts. The site sits on swampland that was covered by Lake Tonawanda, which was a glacier runoff lake formed over 10,000 years ago. It has been confirmed that mastodons would flock there to eat the sodium-rich clay during one of the last great droughts of the Paleolithic.

In August 2008, miners in Romania have unearthed the skeleton of a 2.5 million-year-old mastodon, believed to be one of the best preserved in Europe[20]. Ninety percent of the skeleton's bones were intact, with damage to the skull and tusks[20].

See also

References

- ↑ 2.5 million-year-old mastodon unearthed in Romania

- ↑ "Greek mastodon find 'spectacular'", BBC News (24 July 2007). Retrieved on 2007-07-24.

- ↑ Richard E. Morlan, Bruggeman Mastodon, Canadian Archaeological Radiocarbon Database, www.canadianarchaeology.ca/localc14/c14search.htm, (Hull Quebec: Canadian Museum of Civilization), retrieved online October 2008).

- ↑ Wade E. Miller, “Mammut Americanum: Utah’s First Record of the American Mastodon”, Journal of Paleontology, Volume 61, Number 1, (The Paleontological Society, 1987), 168-183.

- ↑ Margaret Ann Skeels, “The Mastodons and Mammoths of Michigan”, Michigan Academician, Volume XXXIV, Number 3, (Ann Arbor: Michigan Academy of Science, 2002), 254.

- ↑ H. R. Crane and James B. Griffin, Russell Farm, “University of Michigan Radiocarbon Dates IV”, Radiocarbon, Volume 1, Number 1, (New Haven: Yale, 1959), 178.

- ↑ Polaco, O. J.; Arroyo-Cabrales, J.; Corona-M., E.; López-Oliva, J. G. (2001), "The American Mastodon Mammut americanum in Mexico", in Cavarretta, G.; Gioia, P.; Mussi, M. et al., The World of Elephants - Proceedings of the 1st International Congress, Rome October 16-20 2001, Rome: Consiglio Nazionale delle Ricerche, pp. 237-242, ISBN 88-8080-025-6, http://www.cq.rm.cnr.it/elephants2001/pdf/237_242.pdf, retrieved on 2008-07-25

- ↑ Kurtén, Björn and Elaine Anderson. Pleistocene Mammals of North America. New York: Columbia University Press, 1980, p. 344.

- ↑ Kurtén and Anderson, p. 344.

- ↑ Kirk, Ruth and Richard D. Daugherty. Archaeology in Washington. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2007.

- ↑ Allmon, Warren D. and Peter L. Nester, editors. Mastodon Paleobiology, Taphonomy, and Paleoenvironment in the Late Pleistocene of New York State: Studies on the Hyde Park, Chemung, and North Java Sites. Ithaca, N.Y.: Paleontological Research Institution, 2008.

- ↑ http://www.villageofjohnstown.org/history.html

- ↑ Mastodons

- ↑ Agusti, Jordi and Mauricio Anton (2002). Mammoths, Sabretooths, and Hominids. New York: Columbia University Press. pp. 106. ISBN 0-231-11640-3.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 15.3 15.4 Kurtén and Anderson, p. 345

- ↑ Fisher, D. (Oct. 18-21, 2006). "Tusk cementum defects record musth battles in American mastodons". Sixty-Sixth Annual Meeting of the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology.

- ↑ Mastodons Driven to Extinction by Tuberculosis, Fossils Suggest

- ↑ Ward, Peter (1997). "The Call of Distant Mammoths".

- ↑ Flesher, John (2007-09-04). "Possible mastodon carving found on rock", Associated Press. Retrieved on 2007-09-05.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 2.5 million-year-old mastodon unearthed in Romania, USA Today, 2008-08-08, Retrieved on 11 August 2008

External links

- http://www.rmsc.org/MuseumAndScienceCenter/exhibits/GlaciersAndGiants/

- http://www.museum.state.il.us/exhibits/larson/mammut.html

- http://www.calvin.edu/academic/geology/mastodon/calvin_c.htm

- http://www.amnh.org/exhibitions/expeditions/treasure_fossil/Treasures/Warren_Mastodon/warren.html?acts

- http://www.bbc.co.uk/nature/wildfacts/factfiles/3004.shtml

- Greek Mastodon find 'spectacular' (BBC)

- http://www.priweb.org/mastodon/mastodon_home.html

- http://www.mostateparks.com/mastodon.htm

- http://www.slfp.com/Mastodon.htm

- http://www.flmnh.ufl.edu/exhibits

- worlds longest tuska

- [http://westerncentermuseum.org Western Center for Archaeology & Paleontology, home of the largest mastodon ever found in the Western United States