Marginal utility

In economics, the marginal utility of a good or of a service is the utility of the specific use to which an agent would put a given increase in that good or service, or of the specific use that would be abandoned in response to a given decrease. In other words, marginal utility is the utility of the marginal use — which, on the assumption of economic rationality, would be the least urgent use of the good or service, from the best feasible combination of actions in which its use is included.[1][2] Under the mainstream assumptions, the marginal utility of a good or service is the posited quantified change in utility obtained by using one more or one less unit of that good or service.

This concept grew out of attempts by economists to explain the determination of price. The term “marginal utility”, credited to the Austrian economist Friedrich von Wieser by Alfred Marshall,[3] was a translation of Wieser's term “Grenznutzen” (border-use).[1][2]

Contents |

Marginality

Constraints are conceptualized as a border or margin.[4] The location of the margin for any individual corresponds to his or her endowment, broadly conceived to include opportunities. This endowment is determined by many things including physical laws (which constrain how forms of energy and matter may be transformed), accidents of nature (which determine the presence of natural resources), and the outcomes of past decisions made both by others and by the individual himself or herself.

A value that holds true given particular constraints is a marginal value. A change that would be effected as or by a specific loosening or tightening of those constraints is a marginal change, as large as the smallest relevant division of that good or service.[2] For reasons of tractability, it is often assumed in neoclassical analysis that goods and services are continuously divisible. In such context, a marginal change may be an infinitesimal change or a limit. However, strictly speaking, the smallest relevant division may be quite large.

Utility

Different conceptions of utility were and have been employed during and subsequent to the development of theory employing notions of marginal utility. It has been common among economists to describe utility as corresponding to a measure, that is to say, as being quantifiable.[5][6] This has significantly affected the development and reception of theories of marginal utility. Conceptions of utility that entail quantification allow familiar arithmetic operations, and further assumptions of continuity and differentiability greatly increase tractability. However, conceptions without even weak quantification are able to consider rational preferences that would otherwise be excluded.[7]

Benthamite philosophy equated usefulness with the production of pleasure and avoidance of pain,[8] conceptualized as subject to arithmetic operation.[9] British economists, under the influence of this philosophy (especially by way of John Stuart Mill), conceptualized utility as “the feelings of pleasure and pain”[10] and further as a “quantity of feeling” (emphasis added).[11]

The Austrian School more generally attributes value to the satisfaction of needs,[12] did not depend upon a presumption of quantification,[13][7] and sometimes rejects even the possibility of quantification.[14]

The mainstream of contemporary economic theory frequently defers ontological questions, and merely notes or assumes that preference structures conforming to certain rules can be usefully proxied by associating goods, services, or uses thereof with quantities, and defines “utility” as such a quantification.[15] Recognizing that preference may be taken as the determinant of usefulness, this conception doesn't depart from the concept of usefulness.

Under any standard conception, the same object may have different marginal utilities for different people, reflecting different preferences or individual circumstances.

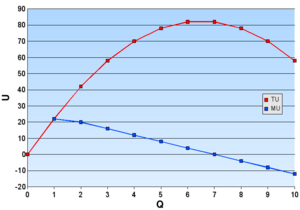

Diminishing marginal utility

An individual will typically be able to partially order the potential uses of a good or service. For example, a ration of water might be used to sustain oneself, a dog, or a rose bush. Say that a given person gives her own sustenance highest priority, that of the dog next highest priority, and lowest priority to saving the roses. In that case, if the individual has two rations of water, then the marginal utility of either of those rations is that of sustaining the dog. The marginal utility of a third unit would be that of watering the roses.

(The diminishing of utility should not necessarily be taken to be itself an arithmetic subtraction. It may be no more than a purely ordinal change.[13][7])

The notion that marginal utilities are diminishing across the ranges relevant to decision-making is called “the law of diminishing marginal utility” (and also known as a “Gossen's First Law”). However, it will not always hold. The case of the person, dog, and roses is one in which potential uses operate independently — there is no complementarity across the three uses. Sometimes an amount added brings things past a desired tipping point, or an amount subtracted causes them to fall short. In such cases, the marginal utility of a good or service might actually be increasing. For example:

- bed sheets, which up to some number may only provide warmth, but after that point may allow one to effect an escape by being tied together into a rope;

- tickets, for travel or theatre, where a second ticket might allow one to take a date on an otherwise uninteresting outing;

- dosages of antibiotics, where having too few pills would leave bacteria with greater resistance, but a full supply could effect a cure.

The fact that a tipping point may be reached does not imply that marginal utility will continue to increase indefinitely thereafter. For example, beyond some point, further doses of antibiotics would kill no pathogens at all.

Independence from presumptions of self-interested behavior

While the above example of water rations conforms to ordinary notions of self-interested behavior, the concept and logic of marginal utility are independent of the presumption that people pursue self-interest.[16] For example, a different person might give highest priority to the rose bush, next highest to the dog, and last to himself. In that case, if the individual has three rations of water, then the marginal utility of any one of those rations is that of watering the person. With just two rations, the person is left unwatered and the marginal utility of either ration is that of the dog. Likewise, a person could give highest priority to the needs of one of her neighbors, next to another, and so forth, placing her own welfare last; the concept of diminishing marginal utility would still apply.

Marginalist theory

Marginalism explains choice with the hypothesis that people decide whether to effect any given change based on the marginal utility of that change, with rival alternatives being chosen based upon which has the greatest marginal utility.

Market price and diminishing marginal utility

If an individual has a stock or flow of a good or service whose marginal utility is less than would be that of some other good or service for which he or she could trade, then it is in his or her interest to effect that trade. Of course, as one thing is traded-away and another is acquired, the respective marginal gains or losses from further trades are now changed. On the assumption that the marginal utility of one is diminishing, and the other is not increasing, all else being equal, an individual will demand an increasing ratio of that which is acquired to that which is sacrificed. (One important way in which all else might not be equal is when the use of the one good or service complements that of the other. In such cases, exchange ratios might be constant.[7]) If any trader can better his or her own marginal position by offering a trade more favorable to complementary traders, then he or she will do so.

In an economy with money, the marginal utility of a quantity is simply that of the best good or service that it could purchase.

Hence, the “law” of diminishing marginal utility provides an explanation for diminishing marginal rates of substitution and thus for the “laws” of supply and demand, as well as essential aspects of models of “imperfect” competition.

The paradox of water and diamonds

The “law” of diminishing marginal utility is said to explain the “paradox of water and diamonds”, most commonly associated with Adam Smith[17] (though recognized by earlier thinkers).[18] Human beings cannot even survive without water, whereas diamonds were in Smith's day mere ornamentation or engraving bits. Yet water had a very low price, and diamonds a very high price, by any normal measure. Marginalists explained that it is the marginal usefulness of any given quantity that determines its price, rather than the usefulness of a class or of a totality. For most people, water was sufficiently abundant that the loss or gain of a gallon would withdraw or add only some very minor use if any; whereas diamonds were in much more restricted supply, so that the lost or gained use would be much greater.

That is not to say that the price of any good or service is simply a function of the marginal utility that it has for any one individual nor for some ostensibly typical individual. Rather, individuals are willing to trade based upon the respective marginal utilities of the goods that they have or desire (with these marginal utilities being distinct for each potential trader), and prices thus develop constrained by these marginal utilities.

The “law” does not tell us such things as why diamonds are naturally less abundant on the earth than is water, but helps us to understand how this affects the value imputed to a given diamond and the price of diamonds in a market.

Quantified marginal utility

Under the special case in which usefulness can be quantified, the change in utility of moving from state  to state

to state  is

is

Moreover, if  and

and  are distinguishable by values of just one variable

are distinguishable by values of just one variable  which is itself quantified, then it becomes possible to speak of the ratio of the marginal utility of the change in

which is itself quantified, then it becomes possible to speak of the ratio of the marginal utility of the change in  to the size of that change:

to the size of that change:

(where “c.p.” indicates that the only independent variable to change is  ).

).

Mainstream neoclassical economics will typically assume that

is well defined, and use “marginal utility” to refer to a partial derivative

and diminishing marginal utility is similarly taken to correspond to

History

Proto-marginalist approaches

Perhaps the essence of a notion of diminishing marginal utility can be found in Aristoteles' Πολιτικά, whereïn he writes

external goods have a limit, like any other instrument, and all things useful are of such a nature that where there is too much of them they must either do harm, or at any rate be of no use[19]

A great variety of economists concluded that there was some sort of inter-relationship between utility and rarity that effected economic decisions, and in turn informed the determination of prices.[20]

Marginalists before the Revolution

The first unambiguous published statement of any sort of theory of marginal utility was by Daniel Bernoulli, in “Specimen theoriae novae de mensura sortis”.[21] This paper appeared in 1738, but a draft had been written in 1731 or in 1732.[22][23] In 1728, Gabriel Cramer had produced fundamentally the same theory in a private letter.[24] Each had sought to resolve the St. Petersburg paradox, and had concluded that the marginal desirability of money decreased as it was accumulated, more specifically such that the desirability of a sum were the natural logarithm (Bernoulli) or square root (Cramer) thereof. However, the more general implications of this hypothesis were not explicated, and the work fell into obscurity.

In “A Lecture on the Notion of Value”, delivered in 1833 and included in Lectures on Population, Value, Poor Laws and Rent (1837), William Forster Lloyd explicitly offered a general marginal utility theory, but did not offer its derivation nor elaborate its implications. The importance of his statement seems to have been lost on everyone (including Lloyd) until the early 20th century, by which time others had independently developed and popularized the same insight.[25]

In An Outline of the Science of Political Economy (1836), Nassau William Senior asserted that marginal utilities were the ultimate determinant of demand, yet apparently did not pursue implications, though some interpret his work as indeed doing just that.[26]

In “De la mesure de l’utilité des travaux publics” (1844), Jules Dupuit applied a conception of marginal utility to the problem of determining bridge tolls.[27]

In 1854, Hermann Heinrich Gossen published Die Entwicklung der Gesetze des menschlichen Verkehrs und der daraus fließenden Regeln für menschliches Handeln, which presented a marginal utility theory and to a very large extent worked-out its implications for the behavior of a market economy. However, Gossen's work was not well received in the Germany of his time, most copies were destroyed unsold, and he was virtually forgotten until rediscovered after the so-called Marginal Revolution.

The Marginal Revolution

- “Marginal revolution” redirects here. For the economics weblog, see Marginal Revolution (blog).

Marginalism eventually found a foot-hold by way of the work of three economists, Jevons in England, Menger in Austria, and Walras in Switzerland.

William Stanley Jevons first proposed the theory in “A General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy” (PDF), a paper presented in 1862 and published in 1863, followed by a series of works culminating in his book The Theory of Political Economy in 1871 that established his reputation as a leading political economist and logician of the time. Jevons' conception of utility was in the utilitarian tradition of Jeremy Bentham and of John Stuart Mill, but he differed from his classical predecessors in emphasizing that "value depends entirely upon utility", in particular, on "final utility upon which the theory of Economics will be found to turn."[28] He later qualified this in deriving the result that in a model of exchange equilibrium, price ratios would be proportional to not only to ratios of "final degrees of utility" but costs of production.[29][30]

Carl Menger presented the theory in Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre (translated as Principles of Economics) in 1871. Menger's presentation is peculiarly notable on two points. First, he took special pains to explain why individuals should be expected to rank possible uses and then to use marginal utility to decide amongst trade-offs. (For this reason, Menger and his followers are sometimes called “the Psychological School”, though they are more frequently known as “the Austrian School” or as “the Vienna School”.) Second, while his illustrative examples present utility as quantified, his essential assumptions do not.[13] (Menger in fact crossed-out the numerical tables in his own copy of the published Grundsätze.[31]) Menger's work found a significant and appreciative audience.

Marie-Esprit-Léon Walras introduced the theory in Éléments d'économie politique pure, the first part of which was published in 1874 in a relatively mathematical exposition. Walras's work found relatively few readers at the time but was recognized and incorporated two decades later in the work of Pareto and Barone.[32]

An American, John Bates Clark, is sometimes also mentioned. But, while Clark independently arrived at a marginal utility theory, he did little to advance it until it was clear that the followers of Jevons, Menger, and Walras were revolutionizing economics. Nonetheless, his contributions thereafter were profound.

The second generation

Although the Marginal Revolution flowed from the work of Jevons, Menger, and Walras, their work might have failed to enter the mainstream were it not for a second generation of economists. In England, the second generation were exemplified by Philip Henry Wicksteed, by William Smart, and by Alfred Marshall; in Austria by Eugen von Böhm-Bawerk and by Friedrich von Wieser; in Switzerland by Vilfredo Pareto; and in America by Herbert Joseph Davenport and by Frank A. Fetter.

There were significant, distinguishing features amongst the approaches of Jevons, Menger, and Walras, but the second generation did not maintain distinctions along national or linguistic lines. The work of von Wieser was heavily influenced by that of Walras. Wicksteed was heavily influenced by Menger. Fetter referred to himself and Davenport as part of “the American Psychological School”, named in imitation of the Austrian “Psychological School”. (And Clark's work from this period onward similarly shows heavy influence by Menger.) William Smart began as a conveyor of Austrian School theory to English-language readers, though he fell increasingly under the influence of Marshall.[33]

Böhm-Bawerk was perhaps the most able expositor of Menger's conception.[34][33] He was further noted for producing a theory of interest and of profit in equilibrium based upon the interaction of diminishing marginal utility with diminishing marginal productivity of time and with time preference.[35] (This theory was adopted in full and then further developed by Knut Wicksell[36] and, with modifications including formal disregard for time-preference, by Wicksell's American rival Irving Fisher.[37])

Marshall was the second-generation marginalist whose work on marginal utility came most to inform the mainstream of neoclassical economics, especially by way of his Principles of Economics, the first volume of which was published in 1890. Marshall constructed the demand curve with the aid of assumptions that utility was quantified, and that the marginal utility of money was constant (or nearly so). Like Jevons, Marshall did not see an explanation for supply in the theory of marginal utility, so he synthesized an explanation of demand thus explained with supply explained in a more classical manner, determined by costs which were taken to be objectively determined. (Marshall later actively mischaracterized the criticism that these costs were themselves ultimately determined by marginal utilities.[38])

The Marginal Revolution and Marxism

In his critique of political economy, Marx discussed “use-value”, a concept analogous to utility:

- A use-value has value only in use, and is realized only in the process of consumption. One and the same use-value can be used in various ways. But the extent of its possible application is limited by its existence as an object with distinct properties. It is, moreover, determined not only qualitatively but also quantitatively. Different use-values have different measures appropriate to their physical characteristics; for example, a bushel of wheat, a quire of paper, a yard of linen.[39]

He acknowledged that “nothing can have value, without being an object of utility”,[40][41] but, in his analysis, “use-value as such lies outside the sphere of investigation of political economy”.[42] and labor determined the measure of market value.

The doctrines of marginalism and the Marginal Revolution are often interpreted as somehow a response to Marxist economics. In fact, the first volume of Das Kapital was not published until July 1867, after the works of Jevons, Menger, and Walras were written or well under way; and Marx was still a relatively obscure figure when these works were completed. It is unlikely that any of them knew anything of him. (On the other hand, Hayek or Bartley has suggested that Marx, voraciously reading at the British Museum, may have come across the works of one or more of these figures, and that his inability to formulate a viable critique may account for his failure to complete any further volumes of Kapital before his death.[43])

Nonetheless, it is not unreasonable to suggest that part of what contributed to the success of the generation who followed the preceptors of the Revolution was their ability to formulate straight-forward responses to Marxist economic theory. The most famous of these was that of Böhm-Bawerk, “Zum Abschluss des Marxschen Systems” (1896),[44] but the first was Wicksteed's “The Marxian Theory of Value. Das Kapital: a criticism” (1884,[45] followed by “The Jevonian criticism of Marx: a rejoinder” in 1885[46]). Only a few Marxist replies were made to marginalism, of which the most famous were Rudolf Hilferding's Böhm-Bawerks Marx-Kritik (1904)[47] and Политической экономии рантье (1914) by Никола́й Ива́нович Буха́рин (Nikolai Bukharin).[48]

(It might also be noted that some followers of Henry George similarly consider marginalism and neoclassical economics a reaction to Progress and Poverty, which was published in 1879.[49])

Eclipse

In his 1881 work Mathematical Psychics, Francis Ysidro Edgeworth presented the indifference curve, deriving its properties from marginalist theory which assumed utility to be a differentiable function of quantified goods and services. Later work attempted to generalize the indifference-curve formulation of utility and marginal utility.

In 1915, Евгений Евгениевич Слуцкий (Eugen Slutsky) derived a theory of consumer choice solely from properties of indifference curves.[50] Because of the World War, the Bolshevik Revolution, and his own subsequent loss of interest, Slutsky's work drew almost no notice, but similar work in 1934 by John Richard Hicks and R. G. D. Allen[51] derived much the same results and found a significant audience. (Allen subsequently drew attention to Slutsky's earlier accomplishment.)

Although some of the third generation of Austrian School economists had by 1911 rejected the quantification of utility while continuing to think in terms of marginal utility,[14] most economists presumed that utility must be a sort of quantity. Indifference curve analysis seemed to represent a way of dispensing with presumptions of quantification, albeït that a seemingly arbitrary assumption (admitted by Hicks to be a “rabbit out of a hat”[52]) about decreasing marginal rates of substitution[53] would then have to be introduced to have convexity of indifference curves.

For those who accepted that indifference curve analysis superseded marginal utility analysis, the latter became at best perhaps pedagogically useful, but “old fashioned” and ultimately incorrect.[53][54]

Revival

When Cramer and Bernoulli introduced the notion of diminishing marginal utility, it had been to address a paradox of gambling, rather than the paradox of value. The marginalists of the revolution, however, had been formally concerned with problems in which there was neither risk nor uncertainty. So too with the indifference curve analysis of Slutsky, Hicks, and Allen.

The expected utility hypothesis of Bernoulli et alii was revived by various 20th century thinkers, with early contributions by Ramsey (1926),[55] v. Neumann and Morgenstern (1944),[56] and Savage (1954).[57] Although this hypothesis remains controversial, it not only brings utility, but a quantified conception of utility, back into the mainstream of economic thought.

A major reason why quantified models of utility are influential today is that risk and uncertainty have been recognized as central topics in contemporary economic theory.[58] Quantified utility models simplify the analysis of risky decisions because, under quantified utility, diminishing marginal utility implies “risk aversion”.[59] In fact, many contemporary analyses of saving and portfolio choice require stronger assumptions than diminishing marginal utility, such as the assumption of “prudence”, which means convex marginal utility.[60]

Meanwhile, the Austrian School continues to develop its ordinalist notions of marginal utility analysis, formally demonstrating that from them proceed the decreasing marginal rates of substitution of indifference curves.[7]

See also

- Economics

- Microeconomics

- Diminishing returns

- Utility

- Marginalism

- Human nature

- Economic subjectivism

References

- See also works named in body of article.

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 von Wieser, Friedrich; Über den Ursprung und die Hauptgesetze des wirtschaftlichen Wertes [The Nature and Essence of Theoretical Economics] (1884), p. 128.

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 Wieser, Friedrich von; Der natürliche Werth [Natural Value] (1889), Bk I Ch V “Marginal Utility” (HTML).

- ↑ Marshall, Alfred; Principles of Economics, Bk 3 Ch 3 Note.

- ↑ Wicksteed, Philip Henry; The Common Sense of Political Economy (1910), Bk I Ch 2 and elsewhere.

- ↑ Stigler, George Joseph; “The Development of Utility Theory”, I and II, Journal of Political Economy (1950), issues 3 and 4.

- ↑ Stigler, George Joseph; “The Adoption of Marginal Utility Theory” History of Political Economy (1972).

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 7.2 7.3 7.4 Mc Culloch, James Huston; “The Austrian Theory of the Marginal Use and of Ordinal Marginal Utility”, Zeitschrift für Nationalökonomie 37 (1977) #3&4 (September).

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy; Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Chapter I §I-III.

- ↑ Bentham, Jeremy; Introduction to the Principles of Morals and Legislation, Chapter IV.

- ↑ Jevons, William Stanley; “Brief Account of a General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society v29 (June 1866) §2.

- ↑ Jevons, William Stanley; “Brief Account of a General Mathematical Theory of Political Economy”, Journal of the Royal Statistical Society v29 (June 1866) §4.

- ↑ Menger, Carl; Grundsätze der Volkswirtschaftslehre (Principles of Economics) Chapter 2 §2.

- ↑ 13.0 13.1 13.2 Georgescu-Roegen, Nicholas; “Utility”, International Encyclopedia of the Social Sciences (1968).

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 von Mises, Ludwig Heinrich; Theorie des Geldes und der Umlaufsmittel (1912).

- ↑ Kreps, David Marc; A Course in Microeconomic Theory, “Chapter two: The theory of consumer choice and demand”, “Utility representations”.

- ↑ Wicksteed, Philip Henry; “The Scope and Method of Political Economy in the Light of the ‘Marginal’ Theory of Value and Distribution”, Economic Journal v24 (1914) #94.

- ↑ Smith, Adam; An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations (1776) Chapter IV. “Of the Origin and Use of Money”.

- ↑ Gordon, Scott (1991). "The Scottish Enlightenment of the eighteenth century". History and Philosophy of Social Science: An Introduction. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-09670-7.

- ↑ Aristoteles; Πολιτικά (translated as Politics), Bk 7 Chapter 1.

- ↑ Přibram, Karl; A History of Economic Reasoning (1983).

- ↑ Bernoulli, Daniel; “Specimen theoriae novae de mensura sortis” in Commentarii Academiae Scientiarum Imperialis Petropolitanae 5 (1738); reprinted in translation as “Exposition of a new theory on the measurement of risk” in Econometrica 22 (1954).

- ↑ Bernoulli, Daniel; letter of 4 July 1731 to Nicolas Bernoulli (excerpted in PDF).

- ↑ Bernoulli, Nicolas; letter of 5 April 1732, acknowledging receipt of “Specimen theoriae novae metiendi sortem pecuniariam” (excerpted in PDF).

- ↑ Cramer, Garbriel; letter of 21 May 1728 to Nicolaus Bernoulli (excerpted in PDF).

- ↑ Seligman, Edwin Robert Anderson; “On some neglected British economists”, Economic Journal v. 13 (September 1903).

- ↑ White, Michael V; “Diamonds Are Forever(?): Nassau Senior and Utility Theory” in The Manchester School of Economic & Social Studies 60 (1992) #1 (March).

- ↑ Dupuit, Jules; “De la mesure de l’utilité des travaux publics”, Annales des ponts et chaussées, Second series, 8 (1844).

- ↑ W. Stanley Jevons (1871), The Theory of Political Economy, p. 111.

- ↑ W. Stanley Jevons (1879, 2nd ed.), The Theory of Political Economy, pp. 208.

- ↑ R.D. Collison Brown (1987), "Jevons, William Stanley," The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics, v. 2, pp. 1008-09.

- ↑ Kauder, Emil; A History of Marginal Utility Theory (1965), p76.

- ↑ Donald A. Walker (1987), "Walras, Léon" The New Palgrave: A Dictionary of Economics]], v. 4, p. 862.

- ↑ 33.0 33.1 Salerno, Joseph T. 1999; “The Place of Mises’s Human Action in the Development of Modern Economic Thought.” Quarterly Journal of Economic Thought v. 2 (1).

- ↑ Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen Ritter von. “Grundzüge der Theorie des wirtschaftlichen Güterwerthes”, Jahrbüche für Nationalökonomie und Statistik v 13 (1886). Translated as Basic Principles of Economic Value.

- ↑ Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen Ritter von; Kapital Und Kapitalizns. Zweite Abteilung: Positive Theorie des Kapitales (1889). Translated as Capital and Interest. II: Positive Theory of Capital with appendices rendered as Further Essays on Capital and Interest.

- ↑ Wicksell, Johan Gustaf Knut; Über Wert, Kapital unde Rente (1893). Translated as Value, Capital and Rent.

- ↑ Fisher, Irving; Theory of Interest (1930).

- ↑ Schumpeter, Joseph Alois; History of Economic Analysis (1954) p 922-3.

- ↑ Marx, Karl Heinrich; A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859).

- ↑ Marx, Karl Heinrich; Capital V1 Ch 1 §1.

- ↑ Marx, Karl Heinrich; Grundrisse (completed in 1857 though not published until much later).

- ↑ Marx, Karl Heinrich; A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy] (1859), p276.

- ↑ Hayek, Friedrich August von, with William Warren Bartley III; The Fatal Conceit: The Errors of Socialism (1988) p150.

- ↑ Böhm-Bawerk, Eugen Ritter von; “Zum Abschluss des Marxschen Systems” [“On the Closure of the Marxist System”], Staatswiss. Arbeiten. Festgabe für K. Knies (1896).

- ↑ Wicksteed, Philip Henry; “Das Kapital: A Criticism”, To-day 2 (1884) p. 388-409.

- ↑ Wicksteed, Philip Henry; “The Jevonian criticism of Marx: a rejoinder”, To-day 3 (1885) p. 177-9.

- ↑ Hilferding, Rudolf; Böhm-Bawerks Marx-Kritik (1904). Translated as Böhm-Bawerk's Criticism of Marx.

- ↑ Буха́рин, Никола́й Ива́нович (Nikolai Ivanovich Bukharin); Политической экономии рантье (1914). Translated as The Economic Theory of the Leisure Class.

- ↑ Gaffney, Mason, and Fred Harrison; The Corruption of Economics (1994).

- ↑ Слуцкий, Евгений Евгениевич (Slutsky, Eugen E.); “Sulla teoria del bilancio del consumatore”, Giornale degli Economisti 51 (1915).

- ↑ Hicks, John Richard, and Roy George Douglas Allen; “A Reconsideration of the Theory of Value”, Economica 54 (1934).

- ↑ Hicks, Sir John Richard; Value and Capital, Chapter I. “Utility and Preference” §8, p23 in the 2nd edition.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 Hicks, Sir John Richard; Value and Capital, Chapter I. “Utility and Preference” §7-8.

- ↑ Samuelson, Paul Anthony; “Complementarity: An Essay on the 40th Anniversary of the Hicks-Allen Revolution in Demand Theory”, Journal of Economic Literature vol 12 (1974).

- ↑ Ramsey, Frank Plumpton; “Truth and Probability” (PDF), Chapter VII in The Foundations of Mathematics and other Logical Essays (1931).

- ↑ von Neumann, John and Oskar Morgenstern; Theory of Games and Economic Behavior (1944).

- ↑ Savage, Leonard Jimmie; Foundations of Statistics (1954).

- ↑ Diamond, Peter, and Michael Rothschild, eds.; Uncertainty in Economics (1989). Academic Press.

- ↑ Demange, Gabriel, and Guy Laroque; Finance and the Economics of Uncertainty (2006), Ch. 3, pp. 71-72. Blackwell Publishing.

- ↑ Kimball, Miles (1990), “Precautionary Saving in the Small and in the Large”, Econometrica, 58 (1) pp. 53-73.