Martin Luther

| Martin Luther | |

Luther in 1529 by Lucas Cranach

|

|

| Born | November 10, 1483 Eisleben, Holy Roman Empire |

|---|---|

| Died | February 18, 1546 (aged 62) Eisleben, Holy Roman Empire |

| Occupation | Theologian, priest |

| Religious beliefs | Lutheran (formerly Roman Catholic) |

| Spouse(s) | Katharina von Bora |

| Children | Hans, Elizabeth, Magdalena, Martin, Paul, Margarethe |

| Parents | Hans and Margarethe Luther (née Lindemann) |

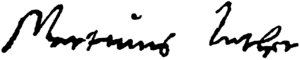

| Signature

|

|

Martin Luther (November 10, 1483 – February 18, 1546) was a German monk,[1] theologian, university professor, Father of Protestantism,[2][3][4][5] and church reformer whose ideas influenced the Protestant Reformation and changed the course of Western civilization.[6]

Luther's theology challenged the authority of the papacy by holding that the Bible is the only infallible source of religious authority[7] and that all baptized Christians under Jesus are a universal priesthood.[8] According to Luther, salvation is a free gift of God, received only by true repentance and faith in Jesus as the Messiah, a faith given by God and unmediated by the church.

At the Diet of Worms assembly over freedom of conscience in 1521, Luther's confrontation with the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V and his refusal to submit to the authority of the Emperor resulted in his being excommunicated from the Roman Catholic Church and being declared an outlaw of the state as a consequence.

His translation of the Bible into the vernacular of the people made the Scriptures more accessible to them, and had a tremendous political impact on the church and on German culture. It furthered the development of a standard version of the German language, added several principles to the art of translation,[9] and influenced the translation of the English King James Bible.[10] His hymns inspired the development of congregational singing within Christianity.[11] His marriage to Katharina von Bora set a model for the practice of clerical marriage within Protestantism.[12]

Much scholarly debate has concentrated on Luther's writings about the Jews. His statements that Jews' homes should be destroyed, their synagogues burned, money confiscated and liberty curtailed were revived and used in propaganda by the Nazis in 1933–45.[13] As a result of this and his revolutionary theological views, his legacy remains controversial.[14]

Early life and the development of his ideas

Birth and education

Martin Luther was born to Hans Luder (or Ludher, later Luther)[15] and his wife Margarethe (née Lindemann) on November 10, 1483 in Eisleben, Germany, then part of the Holy Roman Empire. He was baptized the next morning on the feast day of St. Martin of Tours. His family moved to Mansfeld in 1484, where his father was a leaseholder of copper mines and smelters,[16] and served as one of four citizen representatives on the local council.[15] Martin Marty describes Luther's mother as a hard-working woman of "trading-class stock and middling means," and notes that Luther's enemies would later wrongly describe her as a whore and bath attendant.[15] He had several brothers and sisters, and is known to have been close to one of them, Jacob.[17]

Hans Luther was ambitious for himself and his family, and was determined to see Martin, his eldest son, become a lawyer. He sent Martin to Latin schools in Mansfeld, then Magdeburg in 1497, where he attended a school operated by a lay group called the Brethren of the Common Life, and Eisenach in 1498.[18] The three schools focused on the so-called "trivium": grammar, rhetoric, and logic. Luther later compared his education there to purgatory and hell.[19]

In 1501, at the age of seventeen, he entered the University of Erfurt — which he later described as a beerhouse and whorehouse,[20] — which saw him awakened at four every morning for what has been described as "a day of rote learning and often wearying spiritual exercises."[20] He received his master's degree in 1505.[21]

In accordance with his father's wishes, he enrolled in law school at the same university that year, but dropped out almost immediately, believing that law represented uncertainty.[21] Luther sought assurances about life, and was drawn to theology and philosophy, expressing particular interest in Aristotle, William of Ockham, and Gabriel Biel.[21] He was deeply influenced by two tutors, Bartholomäus Arnoldi von Usingen and Jodocus Trutfetter, who taught him to be suspicious of even the greatest thinkers,[21] and to test everything himself by experience.[22] Philosophy proved to be unsatisfying, offering assurance about the use of reason, but none about the importance, for Luther, of loving God. Reason could not lead men to God, he felt, and he developed a love-hate relationship with Aristotle over the latter's emphasis on reason.[22] For Luther, reason could be used to question men and institutions, but not God. Human beings could learn about God only through divine revelation, he believed, and Scripture therefore became increasingly important to him.[22]

He decided to leave his studies and become a monk, later attributing his decision to an experience during a thunderstorm on July 2, 1505. A lightning bolt struck near him as he was returning to university after a trip home. Later telling his father he was terrified of death and divine judgment, he cried out, "Help! Saint Anna, I will become a monk!"[23] He came to view his cry for help as a vow he could never break.

He left law school, sold his books, and entered a closed Augustinian friary in Erfurt on July 17, 1505.[24] One friend blamed the decision on Luther's sadness over the deaths of two friends. Luther himself seemed saddened by the move. Those who attended a farewell supper walked him to the door of the Black Cloister. "This day you see me, and then, not ever again," he said.[22] His father was furious over what he saw as a waste of Luther's education.[25]

Monastic and academic life

Luther dedicated himself to monastic life, devoting himself to fasting, long hours in prayer, pilgrimage, and frequent confession. Luther tried to please God through this dedication, but it only increased his awareness of his own sinfulness.[26] He would later remark, "If anyone could have gained heaven as a monk, then I would indeed have been among them."[27] Luther described this period of his life as one of deep spiritual despair. He said, "I lost touch with Christ the Savior and Comforter, and made of him the jailor and hangman of my poor soul."[28]

Johann von Staupitz, his superior, concluded that Luther needed more work to distract him from excessive introspection and ordered him to pursue an academic career. In 1507, he was ordained to the priesthood, and in 1508 began teaching theology at the University of Wittenberg.[29] He received a Bachelor's degree in Biblical studies on March 9, 1508, and another Bachelor's degree in the Sentences by Peter Lombard in 1509.[30] On October 19, 1512, he was awarded his Doctor of Theology and, on October 21, 1512, was received into the senate of the theological faculty of the University of Wittenberg, having been called to the position of Doctor in Bible.[31] He spent the rest of his career in this position at the University of Wittenberg.

Indulgences, controversy and the start of the Reformation

- Further information: History of Protestantism

In 1516-17, Johann Tetzel, a Dominican friar and papal commissioner for indulgences, was sent to Germany by the Roman Catholic Church to sell indulgences to raise money to rebuild St Peter's Basilica in Rome.[32] Roman Catholic theology stated that faith alone, whether fiduciary or dogmatic, cannot justify man;[33] and that only such faith as is active in charity and good works (fides caritate formata) can justify man.[34] These good works could be obtained by donating money to the church.

On October 31, 1517, Luther wrote to Albrecht, Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, protesting the sale of indulgences. He enclosed in his letter a copy of his "Disputation of Martin Luther on the Power and Efficacy of Indulgences," which came to be known as The 95 Theses. Hans Hillerbrand writes that Luther had no intention of confronting the church, but saw his disputation as a scholarly objection to church practices, and the tone of the writing is accordingly "searching, rather than doctrinaire."[35] Hillerbrand writes that there is nevertheless an undercurrent of challenge in several of the theses, particularly in Thesis 86, which asks: "Why does the pope, whose wealth today is greater than the wealth of the richest Crassus, build the basilica of St. Peter with the money of poor believers rather than with his own money?"[35]

Luther objected to a saying attributed to Johann Tetzel that "As soon as the coin in the coffer rings, the soul from purgatory springs,"[36] insisting that, since forgiveness was God's alone to grant, those who claimed that indulgences absolved buyers from all punishments and granted them salvation were in error. Christians, he said, must not slacken in following Christ on account of such false assurances.

According to Philipp Melanchthon, writing in 1546, Luther nailed a copy of the 95 Theses to the door of the Castle Church in Wittenberg that same day — church doors acting as the bulletin boards of his time — an event now seen as sparking the Protestant Reformation,[37] and celebrated every October 31 as Reformation Day. Some scholars have questioned the accuracy of Melanchthon's account, noting that no contemporaneous evidence exists for it.[38] Others have countered that no such evidence is necessary, because this was the customary way of advertising an event on a university campus in Luther's day.[39]

The 95 Theses were quickly translated from Latin into German, printed, and widely copied, making the controversy one of the first in history to be aided by the printing press.[40] Within two weeks, the theses had spread throughout Germany; within two months throughout Europe.

Justification by faith

From 1510 to 1520, Luther lectured on the Psalms, the books of Hebrews, Romans, and Galatians. As he studied these portions of the Bible, he came to view the use of terms such as penance and righteousness by the Roman Catholic Church in new ways. He became convinced that the church was corrupt in their ways and had lost sight of what he saw as several of the central truths of Christianity, the most important of which, for Luther, was the doctrine of justification — God's act of declaring a sinner righteous — by faith alone through God's grace. He began to teach that salvation or redemption is a gift of God's grace, attainable only through faith in Jesus as the messiah.[41]

This one and firm rock, which we call the doctrine of justification," he wrote, "is the chief article of the whole Christian doctrine, which comprehends the understanding of all godliness.[42]

Luther came to understand justification as entirely the work of God. Against the teaching of his day that the righteous acts of believers are performed in cooperation with God, Luther wrote that Christians receive such righteousness entirely from outside themselves; that righteousness not only comes from Christ but actually is the righteousness of Christ, imputed to Christians (rather than infused into them) through faith.[43] "That is why faith alone makes someone just and fulfills the law," he wrote. "Faith is that which brings the Holy Spirit through the merits of Christ."[44] Faith, for Luther, was a gift from God. He explained his concept of "justification" in the Smalcald Articles:

The first and chief article is this: Jesus Christ, our God and Lord, died for our sins and was raised again for our justification (Romans 3:24-25). He alone is the Lamb of God who takes away the sins of the world (John 1:29), and God has laid on Him the iniquity of us all (Isaiah 53:6). All have sinned and are justified freely, without their own works and merits, by His grace, through the redemption that is in Christ Jesus, in His blood (Romans 3:23-25). This is necessary to believe. This cannot be otherwise acquired or grasped by any work, law or merit. Therefore, it is clear and certain that this faith alone justifies us ... Nothing of this article can be yielded or surrendered, even though heaven and earth and everything else falls (Mark 13:31).[45]

Response of the papacy

In contrast to the speed with which the theses were distributed, the response of the papacy was painstakingly slow.

Cardinal Albrecht of Hohenzollern, Archbishop of Mainz and Magdeburg, with the consent of Pope Leo X, was using part of the indulgence income to pay his bribery debts,[18] and did not reply to Luther’s letter; instead, he had the theses checked for heresy and forwarded to Rome.[46]

Leo responded over the next three years, "with great care as is proper,"[47] by deploying a series of papal theologians and envoys against Luther. Perhaps he hoped the matter would die down of its own accord, because in 1518 he dismissed Luther as "a drunken German" who "when sober will change his mind".[48]

Widening breach

Luther's writings circulated widely, reaching France, England, and Italy as early as 1519, and students thronged to Wittenberg to hear him speak. He published a short commentary on Galatians and his Work on the Psalms. At the same time, he received deputations from Italy and from the Utraquists of Bohemia; Ulrich von Hutten and Franz von Sickingen offered to place Luther under their protection.[49]

This period of Luther's career was one of his most creative and productive.[50] Three of his best known works were published in 1520: To the Christian Nobility of the German Nation, On the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, and On the Freedom of a Christian.

Finally on May 30, 1519, when the Pope demanded an explanation, Luther wrote a summary and explanation of his theses to the Pope. While the Pope may have conceded some of the points, he did not like the challenge to his authority so he summoned Luther to Rome to answer these. At that point Frederick the Wise, the Saxon Elector, intervened. He did not want one of his subjects to be sent to Rome to be judged by Italians so he prevailed on the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V who needed his support to arrange a compromise.

An arrangement was effected, however, whereby that summons was cancelled, and Luther went to Augsburg in October 1518 to meet the papal legate, Cardinal Thomas Cajetan. The argument was long but nothing was resolved.

Excommunication

On June 15, 1520, the Pope warned Luther with the papal bull (edict) Exsurge Domine that he risked excommunication unless he recanted 41 sentences drawn from his writings, including the 95 Theses, within 60 days.

That autumn, Johann Eck proclaimed the bull in Meissen and other towns. Karl von Miltitz, a papal nuncio, attempted to broker a solution, but Luther, who had sent the Pope a copy of On the Freedom of a Christian in October, publicly set fire to the bull and decretals at Wittenberg on December 10, 1520,[51] an act he defended in Why the Pope and his Recent Book are Burned and Assertions Concerning All Articles.

As a consequence, Luther was excommunicated by Leo X on January 3, 1521, in the bull Decet Romanum Pontificem.

Exile

Diet of Worms

The enforcement of the ban on the 41 sentences fell to the secular authorities. On April 18, 1521, Luther appeared as ordered before the Diet of Worms (Reichstag zu Worms). This was a general assembly (a diet, pronounced dee-et) of the estates of the Holy Roman Empire that took place in Worms (pronounced with the W as a V: Vorms), a town on the Rhine. It was conducted from January 28 to May 25, 1521, with Emperor Charles V presiding. Prince Frederick III, Elector of Saxony, obtained an agreement that Luther would be promised safe passage to and from the meeting.

Johann Eck, speaking on behalf of the Empire as assistant of the Archbishop of Trier, presented Luther with copies of his writings laid out on a table, and asked him if the books were his, and whether he stood by their contents. He confirmed he was the author, but requested time to think about the answer to the second question. He prayed, consulted friends, and gave his response the next day: "Unless I shall be convinced by the testimonies of the Scriptures or by clear reason ... I neither can nor will make any retraction, since it is neither safe nor honourable to act against conscience."[52] He is also famously said to have added: "Hier stehe ich. Ich kann nicht anders. Gott helfe mir. Amen." ("Here I stand. I can do no other. God help me. Amen."). This description of the declaration may be apocryphal,[53] as only the last four words appear in contemporaneous accounts.

Over the next five days, private conferences were held to determine Luther's fate. The Emperor presented the final draft of the Edict of Worms on May 25, 1521, declaring Luther an outlaw, banning his literature, and requiring his arrest: "We want him to be apprehended and punished as a notorious heretic".[54] It also made it a crime for anyone in Germany to give Luther food or shelter. It permitted anyone to kill Luther without legal consequence. The Edict was a divisive move that distressed more moderate men, in particular Desiderius Erasmus.

Exile at Wartburg Castle

Luther's disappearance during his return trip was planned. Frederick III, Elector of Saxony had him discreetly intercepted on his way home by masked horsemen and escorted to the security of the Wartburg Castle at Eisenach, where Luther grew a beard and lived incognito for nearly eleven months, pretending to be a knight called Junker Jörg.[55]

During his stay at Wartburg (May 1521-March 1522), which he referred to as "my Patmos",[56] Luther translated the New Testament from Greek into German, and poured out doctrinal and polemical writings, including in October a renewed attack on Archbishop Albrecht of Mainz, whom he shamed into halting the sale of indulgences in his episcopates,[57] and a "Refutation of the argument of Latomus," in which he expounded the principle of justification to a philosopher from Louvain.[58] In a letter to Melanchthon of August 1, 1521, he wrote:

… let your sins be strong, but let your trust in Christ be stronger, and rejoice in Christ who is the victor over sin, death, and the world. We will commit sins while we are here, for this life is not a place where justice resides.[59]

In On the Abrogation of the Private Mass, in the summer of 1521, Luther widened his target from individual pieties like indulgences and pilgrimages to doctrines at the heart of Church practices. His essay Concerning Confession rejected the Roman Catholic Church's requirement of confession, although he affirmed the value of private confession and absolution. In the introduction to his New Testament — published in September 1522 and selling 5,000 copies in two months — he explained that good works spring from faith; they do not produce it.

In Wittenberg, Andreas Karlstadt, later supported by the ex-Augustinian Gabriel Zwilling, enacted a divisive programme of reform which exceeded anything envisaged by Luther and provoked disturbances, including a revolt by the Augustinian monks against their prior, the smashing of statues and images in churches, and denunciations of the magistracy. After secretly visiting Wittenberg in early December 1521, Luther wrote A Sincere Admonition by Martin Luther to All Christians to Guard Against Insurrection and Rebellion; but Wittenberg became more volatile after Christmas when a band of visionary zealots, the so-called Zwickau prophets, arrived preaching the equality of man, adult baptism, Christ’s imminent return, and other revolutionary doctrines.[57] Luther decided it was time to act.

Return to Wittenberg

- See also: Radical Reformation

Around Christmas 1521, Anabaptists from Zwickau entered Wittenberg and caused considerable civil unrest. Thoroughly opposed to their radical views and fearful of their results, Luther secretly returned to Wittenberg on March 6, 1522. "During my absence," he wrote to the Elector, "Satan has entered my sheepfold, and committed ravages which I cannot repair by writing, but only by my personal presence and living word."[57]

For eight days in Lent, beginning on March 9, Invocavit Sunday, and concluding the following Sunday, Luther preached eight sermons, which became known as the "Invocavit Sermons." In these sermons, he hammered home the primacy of core Christian values such as love, patience, charity, and freedom, and reminded the citizens to trust God's word rather than violence to bring about necessary change.

Do you know what the Devil thinks when he sees men use violence to propagate the gospel? He sits with folded arms behind the fire of hell, and says with malignant looks and frightful grin: "Ah, how wise these madmen are to play my game! Let them go on; I shall reap the benefit. I delight in it." But when he sees the Word running and contending alone on the battle-field, then he shudders and shakes for fear.[57]

The effect of Luther’s intervention was instantaneous. After the sixth sermon, Jerome Schurf wrote to the elector: "Oh, what joy has Dr. Martin’s return spread among us! His words, through divine mercy, are bringing back every day misguided people into the way of the truth."[57]

Luther next set about reversing or softening some of the new church practices and worked alongside the authorities to restore public order, signaling his reinvention as a conservative force within the Reformation. After banishing the Zwickau prophets, who abused him as a new pope, he now faced a battle not only against the corrupt and distorted practices of the established Church but against those on his own side who threatened the new order by fomenting social unrest and even violence.[57]

Marriage and family

On the evening of June 13, 1525, Luther married Katharina von Bora, one of a group of 12 nuns he had helped escape from the Nimbschen Cistercian convent in April 1523, arranging for them to be smuggled out in herring barrels. "Suddenly, and while I was occupied with far different thoughts," he wrote to his friend Link, "the Lord has plunged me into marriage."[60] Katharina was twenty-six years old, Luther forty-two.

A few priests and former monks had already married, including Andreas Karlstadt and Justus Jonas, but Luther’s marriage set the seal of approval on clerical marriage. He had long condemned vows of celibacy on biblical grounds, but his decision to marry surprised many, not least Melanchthon, who called it reckless.[61] Luther had written to Spalatin on November 30, 1524, "I shall never take a wife, as I feel at present. Not that I am insensible to my flesh or sex (for I am neither wood nor stone); but my mind is averse to wedlock because I daily expect the death of a heretic." Melanchthon reveals in a letter that prior to his marriage, Luther had been living on the plainest food, and that his mildewed bed was not properly made for months at a time.[62]

Luther and Katharina moved into a former monastery "The Black Cloister," a wedding present from the new elector John Frederick, and embarked upon what appears to have been a happy and successful marriage. Between bearing six children, Katharina, whose judgement Luther respected, helped earn the couple a living by farming the land and taking in boarders.[63] Luther confided to Stiefel on August 11, 1526: "Catharina, my dear rib ... is, thanks to God, gentle, obedient, compliant in all things, beyond my hopes. I would not exchange my poverty for the wealth of Croesus."[62]

By the time of Katharina's death, the surviving of the five Luther children were adults. Hans studied law and became a court advisor. Martin studied theology, but never had a regular pastoral call. Paul became a physician. He fathered six children, and the male line of the Luther family continued through him to John Ernest Luther, ending in 1759. Margaretha Luther, born in Wittenberg on December 17, 1534, married into a noble and wealthy Prussian family, to Georg von Kunheim (Wehlau, July 1, 1523 – Mühlhausen, October 18, 1611, the son of Georg von Kunheim (1480 – 1543) and wife Margarethe, Truchsessin von Wetzhausen (1490 – 1527) but died in Mühlhausen in 1570 at the age of thirty-six. However, her descendants have continued to the present, and include President Paul von Hindenburg, the Counts zu Eulenburg, and Princes zu Eulenburg und Hertefeld.

Peasants' War

Despite his victory in Wittenberg, Luther was unable to stifle radicalism further afield. Preachers such as Zwickau prophet Nicholas Storch and Thomas Müntzer — whose rallying cry was "let not your sword grow cold from blood" —[57] helped instigate the Peasants' War in 1524, during which many atrocities were committed, often in Luther's name. This war was being pursued by the peasantry in order to establish a classless society with shared goods. In 1525, Müntzer eventually succeeded in establishing a short-lived communist theocracy.

There had been revolts by the peasantry on a smaller scale since the 15th century;[57] many of the peasants now believed that Luther's attack on the Church and the hierarchy meant that the reformers would support an attack on the upper classes in general, because of the close ties between the secular princes and the princes of the Church. Revolts broke out in Swabia, Franconia, and Thuringia in 1524, gaining support from disaffected nobles too, many of whom were in debt. Gaining momentum and a new leader in Thomas Müntzer, the revolts turned into war.[57]

Luther sympathized with the peasants' grievances, as he showed in his response to the Twelve Articles of the Black Forest in May 1525,[57] but he reminded them to obey the temporal authorities and became enraged at the widespread burning of convents, monasteries, bishops’ palaces, and libraries. In Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants (1525), he explained the Gospel teaching on wealth, condemned the violence as the devil's work, and called for the nobility to put down the rebels like mad dogs:

Therefore let everyone who can, smite, slay, and stab, secretly or openly, remembering that nothing can be more poisonous, hurtful, or devilish than a rebel ... For baptism does not make men free in body and property, but in soul; and the gospel does not make goods common, except in the case of those who, of their own free will, do what the apostles and disciples did in Acts 4 [:32–37]. They did not demand, as do our insane peasants in their raging, that the goods of others—of Pilate and Herod—should be common, but only their own goods. Our peasants, however, want to make the goods of other men common, and keep their own for themselves. Fine Christians they are! I think there is not a devil left in hell; they have all gone into the peasants. Their raving has gone beyond all measure.[64]

In Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants Luther opposed the peasant movement for three reasons. First, instead of conducting themselves appropriately by lawfully submitting to the secular government, the peasants chose to resort to violence, therefore failing to heed Christ's counsel to "Render unto Caesar the things that are Caesar's." Second, due to the peasant's violent actions of rebelling, robbing, and plundering, Luther explained that they were "outside the law of God and Empire," therefore meriting "death in body and soul, if only as highwaymen and murderers." Lastly, Luther presented how the peasants "cloak this terrible and horrible sin with the Gospel" and call themselves "Christian brethren," sins which Luther considered utter blasphemy.[65] Interestingly, according to scholar H.O.J. Brown, Against the Murderous, Thieving Hordes of Peasants was actually published a few weeks after the Battle of Frankenhausen, therefore Luther cannot be blamed for the bloodshed at that key battle. It appears the Nobles would have put down the rebellion with or without Luther's urging.

Without Luther's backing for the uprising, many rebels laid down their weapons; others felt betrayed. Their defeat by the Swabian League at the Battle of Frankenhausen on May 25, 1525, followed by Müntzer’s execution, brought the revolutionary stage of the Reformation to a close.[57] Thereafter, radicalism found a refuge in the anabaptist movement, while Luther's Reformation flourished under the wing of the secular powers.

Catechisms

In 1528, Luther visited parishes and schools in Saxony to determine the quality of pastoral care and Christian education. He wrote in the preface to The Small Catechism: "Mercy! Good God! what manifold misery I beheld! The common people, especially in the villages, have no knowledge whatever of Christian doctrine, and, alas! many pastors are altogether incapable and incompetent to teach."[66]

In response, he prepared the Small Catechism and Large Catechism, instructional and devotional material on the Ten Commandments, the Apostles' Creed, the Lord's Prayer, baptism, confession and absolution, and the Lord's Supper. The Small Catechism was supposed to be read by the people themselves, and the Large Catechism by the pastors; both remain popular instructional materials among Lutherans. Luther, who was modest about the publishing of his collected works, thought his catechisms were one of two works he would not be embarrassed to call his own: "Regarding the plan to collect my writings in volumes, I am quite cool and not at all eager about it because, roused by a Saturnian hunger, I would rather see them all devoured. For I acknowledge none of them to be really a book of mine, except perhaps the one Bondage of the Will and the Catechism."[67]

Luther's translation of the Bible

Luther translated the Bible from Greek into German to make it more accessible to ordinary people, a task he began alone in 1521 during his stay in the Wartburg castle. He was not the first translator of it into German, but he was by far the greatest, according to Philip Shaff, who writes that, had Luther done nothing but this, he would remain one of the "greatest benefactors of the German-speaking race."[68]

His translation of The New Testament was published in September 1522 and, in collaboration with Johannes Bugenhagen, Justus Jonas, Caspar Creuziger, Philipp Melanchthon, Matthäus Aurogallus, and George Rörer, the Old and New Testaments together in 1534. He worked on refining the translation for the rest of his life.

The Luther Bible contributed to the emergence of the modern German language and is regarded as a landmark in German literature. The 1534 edition was influential on William Tyndale's translation,[69] a precursor of the King James Bible.[70] Philip Schaff, the 19th century theologian, said of the work:

The richest fruit of Luther's leisure in the Wartburg, and the most important and useful work of his whole life, is the translation of the New Testament, by which he brought the teaching and example of Christ and the Apostles to the mind and heart of the Germans in life-like reproduction. It was a republication of the gospel. He made the Bible the people's book in the church, school and home.[71]

Liturgy and church government

Luther's German Mass of 1526 provided for weekday services and for catechetical instruction. He strongly objected to making a new law of the forms and urged the retention of other good liturgies. While advocating Christian liberty in liturgical matters, he also spoke out in favor of maintaining and establishing liturgical uniformity among those sharing the same faith in a given area.[72]

He saw in liturgical uniformity a fitting outward expression of unity in the faith, while in liturgical variation, an indication of possible doctrinal variation. He did not consider liturgical change a virtue, especially when it might be made by individual Christians or congregations: he was content to conserve and reform what the Church had inherited from the past. He eliminated and condemned those parts of the Roman Catholic Mass that taught that the Eucharist was a propitiatory sacrifice and the body and blood of Christ by transubstantiation,[73] but retained the use of historic liturgical forms and customs.

Eucharist controversy

Luther's views on the Eucharist — the sacrament of the Lord's Supper — were put to the test in October 1529 at the Marburg Colloquy, an assembly of Protestant theologians gathered by Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, to establish doctrinal unity in the emerging Protestant states. Agreement was achieved on most points, the exception being the nature of the Eucharist, an issue crucial to Luther.[74]

The theologians, including Zwingli, Andreas Karlstadt, Leo Jud, and Johannes Oecolampadius, differed on the significance of the words spoken by Jesus at the Last Supper: "This is my body which is for you," "This cup is the new covenant in my blood" (1 Corinthians 11:23–26). Luther insisted on the Real Presence of the body and blood of Christ in the consecrated bread and wine, but the other theologians believed God to be only symbolically present: Zwingli, for example, denied Jesus's ability to be in more than one place at a time. But Luther, who affirmed the doctrine of Hypostatic Union, that Jesus is both man and God, was clear:

For I do not want to deny in any way that God’s power is able to make a body be simultaneously in many places, even in a corporeal and circumscribed manner. For who wants to try to prove that God is unable to do that? Who has seen the limits of his power?[75]

Even more forcefully, Luther expressed his belief in the real presence in a letter to the Christians in Strassburg, Dec. 15, 1524:

This much I confess: if Dr Karlstadt or any one else could have convinced me five years ago that there was nothing but bread and wine in the sacrament, he would have rendered me a great service. I have undergone great temptations, and struggled and striven to get free of this because I saw clearly that with this I could have given the severest blow to popery. [...][76] But I am bound; I cannot get free of it; the text is too strong, and cannot be wrested from its sense by words.[77]

Despite these disagreements on the Eucharist, the Marburg Colloquy paved the way for the signing in 1530 of the Augsburg Confession, and for the formation of the Schmalkaldic League the following year by leading Protestant nobles such as Philip of Hesse, John Frederick of Saxony, and Georg, Margrave of Brandenburg-Ansbach. According to Luther, agreement in the faith was not necessary prior to entering political alliances. Nevertheless, interpretations of the Eucharist differ among Protestants to this day.

Augsburg Confession

- Further information: Augsburg Confession and Apology of the Augsburg Confession

Charles V, the Holy Roman Emperor, convened an Imperial Diet in Augsburg in 1530 with the goal of uniting the empire against the Ottoman Turks, who had besieged Vienna the previous autumn.

To achieve unity, Charles required a resolution of the religious controversies in his realm. Luther, still under the Imperial Ban, was left behind at the Coburg fortress while his elector and colleagues from Wittenberg attended the diet. The Augsburg Confession, a summary of the Lutheran faith authored by Philipp Melanchthon but influenced by Luther,[78] was read aloud to the emperor. It was the first Lutheran confession included in the Book of Concord of 1580, and is regarded as the principal confession of the Lutheran Church.

Philip of Hesse controversy

In 1539, Luther became involved in controversy surrounding the bigamy of Philip I, Landgrave of Hesse, who wanted to marry one of his wife's ladies-in-waiting. He accordingly wrote Luther for his opinion, alleging as a precedent the polygamy of the patriarchs; but Luther replied that it was not enough for a Christian to consider the acts of the patriarchs, but that he, like the patriarchs, must have special divine sanction. Since, however, such sanction was lacking in the present case, Luther advised against such a marriage, especially for Christians, unless there was extreme necessity, as, for example, if the wife was leprous, or abnormal in other respects. Despite this discouragement, Philip gave up neither his project nor a life of sensuality which kept him for years from receiving communion.

Luther and antisemitism

Historian Robert Michael writes that Luther was concerned with the Jewish question all his life, despite devoting only a small proportion of his work to it.[79] As a Christian pastor and theologian Luther was concerned that people have faith in Jesus as the messiah for salvation. In rejecting that view of Jesus, the Jews became the "quintessential other,"[80] a model of the opposition to the Christian view of God. In an early work, That Jesus Christ was born a Jew, Luther advocated kindness toward the Jews, but only with the aim of converting them to Christianity: what was called Judenmission.[81] When his efforts at conversion failed, he became increasingly bitter toward them.[82] His main works on the Jews were his 60,000-word treatise Von den Juden und Ihren Lügen (On the Jews and Their Lies), and Vom Schem Hamphoras und vom Geschlecht Christi (On the Holy Name and the Lineage of Christ) — reprinted five times within his lifetime — both written in 1543, three years before his death.[83] He argued that the Jews were no longer the chosen people, but were "the devil's people." They were "base, whoring people, that is, no people of God, and their boast of lineage, circumcision, and law must be accounted as filth."[84] The synagogue was a "defiled bride, yes, an incorrigible whore and an evil slut ..."[85] and Jews were full of the "devil's feces ... which they wallow in like swine."[86] He advocated setting synagogues on fire, destroying Jewish prayerbooks, forbidding rabbis from preaching, seizing Jews' property and money, smashing up their homes, and ensuring that these "poisonous envenomed worms" be forced into labor or expelled "for all time."[87] He also seemed to sanction their murder,[88] writing "We are at fault in not slaying them."[89]

Luther successfully campaigned against the Jews in Saxony, Brandenburg, and Silesia. Josel of Rosheim (1480-1554), who tried to help the Jews of Saxony, wrote in his memoir that their situation was "due to that priest whose name was Martin Luther — may his body and soul be bound up in hell!! — who wrote and issued many heretical books in which he said that whoever would help the Jews was doomed to perdition."[90] Michael writes that Josel asked the city of Strasbourg to forbid the sale of Luther's anti-Jewish works; they refused initially, but relented when a Lutheran pastor in Hochfelden argued in a sermon that his parishioners should murder Jews.[91] Luther's influence persisted after his death. Throughout the 1580s, riots saw the expulsion of Jews from several German Lutheran states.[91][92]

According to Michael, Luther's work acquired the status of Scripture within Germany, and he became the most widely read author of his generation, in part because of the coarse and passionate nature of the writing.[91] The prevailing view[93] among historians is that his anti-Jewish rhetoric contributed significantly to the development of antisemitism in Germany,[94] and in the 1930s and 1940s provided an ideal foundation for the National Socialist's attacks on Jews.[95] Reinhold Lewin writes that "whoever wrote against the Jews for whatever reason believed he had the right to justify himself by triumphantly referring to Luther." According to Michael, just about every anti-Jewish book printed in the Third Reich contained references to and quotations from Luther. Heinrich Himmler wrote admiringly of his writings and sermons on the Jews in 1940.[96] The city of Nuremberg presented a first edition of On the Jews and their Lies to Julius Streicher, editor of the Nazi newspaper Der Stürmer, on his birthday in 1937; the newspaper described it as the most radically anti-Semitic tract ever published.[97] It was publicly exhibited in a glass case at the Nuremberg rallies and quoted in a 54-page explanation of the Aryan Law by Dr. E.H. Schulz and Dr. R. Frercks.[82] On December 17, 1941, seven Lutheran regional church confederations issued a statement agreeing with the policy of forcing Jews to wear the yellow badge, "since after his bitter experience Luther had already suggested preventive measures against the Jews and their expulsion from German territory."

At the heart of the debate about Luther's influence is whether it is anachronistic to view his work as a precursor of the racial antisemitism of the National Socialists. Some scholars see Luther's influence as limited, and the Nazis' use of his work as opportunistic. Martin Brecht argues that there is a world of difference between Luther's belief in salvation, which depended on a faith in Jesus as the messiah — a belief Luther criticized the Jews for rejecting — and the Nazis' ideology of racial antisemitism.[98] Johannes Wallmann argues that Luther's writings against the Jews were largely ignored in the 18th and 19th centuries, and that there is no continuity between Luther's thought and Nazi ideology.[99] Uwe Siemon-Netto agrees, arguing that it was because the Nazis were already anti-Semites that they revived Luther's work.[100][101] Hans J. Hillerbrand agrees that to focus on Luther is to adopt an essentially ahistorical perspective of Nazi antisemitism that ignores other contributory factors in German history.[102][103] Other scholars argue that, even if his views were merely anti-Judaic, their violence lent a new element to the standard Christian suspicion of Judaism. Ronald Berger writes that Luther is credited with "Germanizing the Christian critique of Judaism and establishing anti-Semitism as a key element of German culture and national identity."[104] Paul Rose argues that he caused a "hysterical and demonizing mentality" about Jews to enter German thought and discourse, a mentality that might otherwise have been absent.[105]

Since the 1980s, Lutheran Church denominations have repudiated Martin Luther's antisemitic views.

Among Luther's antisemitic writings in On the Jews and Their Lies (1543), Chapter XI is the most vitriolic.

Final years and death

Luther had been suffering from ill health for years, including constipation, hemorrhoids, Ménière's disease (vertigo, fainting, and tinnitus), and a cataract in one eye.[106] From 1531–1546, his health deteriorated further. The years of struggle with Rome, the antagonisms with and among his fellow reformers, and the scandal which ensued from the bigamy of the Philip of Hesse incident, in which Luther had played a leading role, all may have contributed. In 1536, he began to suffer from kidney and bladder stones, and arthritis, and an ear infection ruptured an ear drum. In December 1544, he began to feel the effects of angina.[107]

His physical health made him short-tempered and even harsher in his writings and comments. His wife Katie was overheard saying, "Dear husband, you are too rude," and he responded, "They are teaching me to be rude."[108]

His last sermon was delivered at Eisleben, his place of birth, on February 15, 1546, three days before his death.[109] It was "entirely devoted to the obdurate Jews, whom it was a matter of great urgency to expel from all German territory," according to Léon Poliakov.[110] James Mackinnon writes that it concluded with a "fiery summons to drive the Jews bag and baggage from their midst, unless they desisted from their calumny and their usury and became Christians."[111] Luther said, "we want to practice Christian love toward them and pray that they convert," but also that they are "our public enemies ... and if they could kill us all, they would gladly do so. And so often they do."[112]

Luther's final journey, to Mansfeld, was taken due to his concern for his siblings' families continuing in their father Hans Luther's copper mining trade. Their livelihood was threatened by Count Albrecht of Mansfeld bringing the industry under his own control. The controversy that ensued involved all four Mansfeld counts: Albrecht, Philip, John George, and Gerhard. Luther journeyed to Mansfeld twice in late 1545 to participate in the negotiations for a settlement, and a third visit was needed in early 1546 for their completion.

The negotiations were successfully concluded on February 17, 1546. After 8:00 p.m., he experienced chest pains. When he went to his bed, he prayed, "Into your hand I commit my spirit; you have redeemed me, O Lord, faithful God" (Ps. 31:5), the common prayer of the dying. At 1:00 a.m. he awoke with more chest pain and was warmed with hot towels. He thanked God for revealing his son to him in whom he had believed. His companions, Justus Jonas and Michael Coelius, shouted loudly, "Reverend father, are you ready to die trusting in your Lord Jesus Christ and to confess the doctrine which you have taught in his name?" A distinct "Yes" was Luther's reply. (It was believed at the time that sudden cardiac arrest or stroke was a sign that Satan had taken a man's soul; Luther's companions stressed that he had gradually weakened and commended himself into God's hands.[113])

An apoplectic stroke deprived him of his speech, and he died shortly afterwards at 2:45 a.m., February 18, 1546, aged 62, in Eisleben, the city of his birth. He was buried in the Castle Church in Wittenberg, beneath the pulpit.[114]

A piece of paper was later found on which he had written his last statement. The statement was in Latin, apart from "We are beggars," which was in German.

1. No one can understand Vergil's Bucolics unless he has been a shepherd for five years. No one can understand Vergil's Georgics, unless he has been a farmer for five years. 2. No one can understand Cicero's Letters (or so I teach), unless he has busied himself in the affairs of some prominent state for twenty years. 3. Know that no one can have indulged in the Holy Writers sufficiently, unless he has governed churches for a hundred years with the prophets, such as Elijah and Elisha, John the Baptist, Christ and the apostles. Do not assail this divine Aeneid; nay, rather prostrate revere the ground that it treads. We are beggars: this is true.[115][116]

Recent trends in research

Modern Luther scholarship has presented a more diverse view of Luther. Research lead by Tuomo Mannermaa at the University of Helsinki has led to the development of the The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther that describes Luther's views on salvation in terms much closer to Eastern Orthodox notions of theosis rather than established interpretations of German Luther scholarship.[117] This research has recently been presented in English in an anthology of papers edited by Carl E. Braaten and Robert W. Jenson in a work entitled, Union with Christ: The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther. Mannermaa states, "the external impulse for this new wave of Luther studies in Helsinki came surprisingly from outside the boundaries of Luther research. It came from the ecumenical dialogue between the Evangelical Lutheran Church of Finland and the Russian Orthodox Church that was initiated by Archbishop Martti Simojoki at the beginning of the nineteen-seventies."[118] This research has been called into question because it ignores Luther's roots and theological development in Western Christendom, and it characterizes Luther's teaching on Justification as based on Jesus' righteousness which indwells the believer rather than Jesus' righteousness as imputed to the believer.[119]

Beginning in 1955, a new English translation of Luther's major works was carried out as a joint venture of Concordia Publishing House and Fortress, now Augsburg Fortress Press. Known as the "American Edition of Luther's Works,"[120] it has led to the rediscovery of some of Luther's most controversial writings, and a more complete picture has emerged of this prolific writer and his complex personality.

The "American Edition" translation of On the Jews and Their Lies in 1971, possibly the first complete English version,[121] revealed to many readers a side of Luther they had not previously known. Another of Luther's works, Vom Schem Hamphoras, was translated and published independently as part of The Jew In Christian Theology by Gerhard Falk in 1992.[122] Luther's Vom Schem Hamphoras continues his graphic and polemical satire against and his castigation of the Jews, but it does not exceed the violently graphic and religiously zealous anti-Jewish diatribe of On the Jews and Their Lies.

The "American Edition" also brought to English readers Against the Papacy at Rome Founded by the Devil (1545),[123] which has been described as "one of Luther's most coarse and vehement works." It is said to contain scatological satires of the Pope, with illustrations by Cranach, who is known for painting Luther’s portrait.[124] These "were so inexpressibly vile that a common impulse of decency demanded their summary suppression by his friends."[125]

Against Hanswurst (1541) was also translated as part of the "American Edition"[126] and is described as "rivaling his anti-Jewish treatises for vulgarity and violence of expression."[127]

Literary treatments

- The Nightingale of Wittenburg by August Strindberg (German title, Luther)

See also

- 2008 Europe Taler coin, on which Luther is one of the historical figures featured.

- Christianity and anti-Semitism

- Consubstantiation

- Erasmus' Correspondents

- Jan Hus

- John Calvin

- John Wycliffe

- Luther's Seal

- Martin Luther's views on Mary

- Role of the printing press in the Reformation

- Theology of Martin Luther

References

- ↑ Plass, Ewald M. "Monasticism," in What Luther Says: An Anthology. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1959, 2:964.

- ↑ Challenges to Authority: The Renaissance in Europe: A Cultural Enquiry, Volume 3, by Peter Elmer, page 25

- ↑ "Martin Luther: Biography." AllSands.com. July 26, 2008 http://www.allsands.com/potluck3/martinlutherbi_ugr_gn.htm>.

- ↑ "What ELCA Lutherns Believe." Evangelical Lutheran Church in America. July 26, 2008 [1].

- ↑ Saraswati, Prakashanand. The True History and the Religion of India : A Concise Encyclopedia of Authentic Hinduism. New York: Motilal Banarsidass (Pvt. Ltd), 2001. "His 'protest for reformation' coined the term Protestant, so he was called the father of Protestantism."

- ↑ Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther: Significance," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007.

- ↑ Ewald M. Plass, What Luther Says, 3 vols., (St. Louis: CPH, 1959), 88, no. 269; M. Reu, Luther and the Scriptures, Columbus, Ohio: Wartburg Press, 1944), 23.

- ↑ Luther, Martin. Concerning the Ministry (1523), tr. Conrad Bergendoff, in Bergendoff, Conrad (ed.) Luther's Works. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1958, 40:18 ff.

- ↑ Fahlbusch, Erwin and Bromiley, Geoffrey William. The Encyclopedia of Christianity. Grand Rapids, MI: Leiden, Netherlands: Wm. B. Eerdmans; Brill, 1999–2003, 1:244.

- ↑ Tyndale's New Testament, trans. from the Greek by William Tyndale in 1534 in a modern-spelling edition and with an introduction by David Daniell. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1989, ix–x.

- ↑ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 269.

- ↑ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 223.

- ↑ McKim, Donald K. (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Martin Luther. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 58; Berenbaum, Michael. "Anti-Semitism," Encyclopaedia Britannica, accessed January 2, 2007. For Luther's own words, see Luther, Martin. "On the Jews and Their Lies," tr. Martin H. Bertram, in Sherman, Franklin. (ed.) Luther's Works. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971, 47:268–72.

- ↑ Hendrix, Scott H. "The Controversial Luther", Word & World 3/4 (1983), Luther Seminary, St. Paul, MN, p. 393: "And, finally, after the Holocaust and the use of his anti-Jewish statements by National Socialists, Luther's anti-semitic outbursts are now unmentionable, though they were already repulsive in the sixteenth century. As a result, Luther has become as controversial in the twentieth century as he was in the sixteenth." Also see Hillerbrand, Hans. "The legacy of Martin Luther", in Hillerbrand, Hans & McKim, Donald K. (eds.) The Cambridge Companion to Luther. Cambridge University Press, 2003.

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Marty, Martin. Martin Luther. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 1.

- ↑ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:3–5.

- ↑ Marty, Martin. Martin Luther. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 3.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 18.2 Rupp, Ernst Gordon. "Martin Luther," Encyclopædia Britannica, accessed 2006.

- ↑ Marty, Martin. Martin Luther. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 2-3.

- ↑ 20.0 20.1 Marty, Martin. Martin Luther. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 4.

- ↑ 21.0 21.1 21.2 21.3 Marty, Martin. Martin Luther. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 5.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 Marty, Martin. Martin Luther. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 6.

- ↑ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:48.

- ↑ Schwiebert, E.G. Luther and His Times. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1950, 136.

- ↑ Marty, Martin. Martin Luther. Viking Penguin, 2004, p. 7.

- ↑ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 40-42.

- ↑ Kittelson, James. Luther The Reformer. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishing House, 1986), 53.

- ↑ Kittelson, James. Luther The Reformer. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishing House, 1986, 79.

- ↑ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 44-45.

- ↑ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:93.

- ↑ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:12-27.

- ↑ "Johann Tetzel," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007: "Tetzel's experiences as a preacher of indulgences, especially between 1503 and 1510, led to his appointment as general commissioner by Albrecht, archbishop of Mainz, who, deeply in debt to pay for a large accumulation of benefices, had to contribute a considerable sum toward the rebuilding of St. Peter's Basilica in Rome. Albrecht obtained permission from Pope Leo X to conduct the sale of a special plenary indulgence (i.e., remission of the temporal punishment of sin), half of the proceeds of which Albrecht was to claim to pay the fees of his benefices. In effect, Tetzel became a salesman whose product was to cause a scandal in Germany that evolved into the greatest crisis (the Reformation) in the history of the Western church."

- ↑ (Trent, l. c., can. xii: "Si quis dixerit, fidem justificantem nihil aliud esse quam fiduciam divinae misericordiae, peccata remittentis propter Christum, vel eam fiduciam solam esse, qua justificamur, a.s.")

- ↑ (cf. Trent, Sess. VI, cap. iv, xiv)

- ↑ 35.0 35.1 Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther: Indulgences and salvation," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007.

- ↑ Bainton, Roland. Here I Stand: a Life of Martin Luther. New York: Penguin, 1995, 60; Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:182; Kittelson, James. Luther The Reformer. Minneapolis: Augsburg Fortress Publishing House, 1986),104.

- ↑ "Luther's lavatory thrills experts", BBC News, October 22, 2004.

- ↑ Iserloh, Erwin. The Theses Were Not Posted. Toronto: Saunders of Toronto, Ltd., 1966.

- ↑ Junghans, Helmer. "Luther's Wittenberg," in McKim, Donald K. (ed.) The Cambridge Companion to Martin Luther. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 26.

- ↑ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 1:204-205.

- ↑ Wriedt, Markus. "Luther's Theology," in The Cambridge Companion to Luther. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2003, 88–94.

- ↑ Bouman, Herbert J. A. "The Doctrine of Justification in the Lutheran Confessions", Concordia Theological Monthly, November 26, 1955, No. 11:801.

- ↑ Dorman, Ted M., "Justification as Healing: The Little-Known Luther," Quodlibet Journal: Volume 2 Number 3, Summer 2000. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ "Luther's Definition of Faith".

- ↑ Luther, Martin. "The Smalcald Articles," in Concordia: The Lutheran Confessions. (Saint Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 2005, 289, Part two, Article 1.

- ↑ Treu, Martin. Martin Luther in Wittenberg: A Biographical Tour. Wittenberg: Saxon-Anhalt Luther Memorial Foundation, 2003, 31.

- ↑ Papal Bull Exsurge Domine.

- ↑ Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910, 7:99; Polack, W.G. The Story of Luther. St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1931, 45.

- ↑ Macauley Jackson, Samuel and Gilmore, George William. (eds.) "Martin Luther", The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, New York, London, Funk and Wagnalls Co., 1908–1914; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1951), 71.

- ↑ Spitz, Lewis W. The Renaissance and Reformation Movements, St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1987, 338.

- ↑ Brecht, Martin. (tr. Wolfgang Katenz) "Luther, Martin," in Hillerbrand, Hans J. (ed.) Oxford Encyclopedia of the Reformation. New York: Oxford University Press, 1996, 2:463.

- ↑ Macauley Jackson, Samuel and Gilmore, George William. (eds.) "Martin Luther", The New Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge, New York, London, Funk and Wagnalls Co., 1908–1914; Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Book House, 1951), 72.

- ↑ Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther: Diet of Worms," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007.

- ↑ Bratcher, Dennis. "The Edict of Worms (1521)," in The Voice: Biblical and Theological Resources for Growing Christians. Retrieved July 13, 2007.

- ↑ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin," 72.

- ↑ Luther, Martin. "Letter 82," in Luther's Works. Jaroslav Jan Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald and Helmut T. Lehmann (eds), Vol. 48: Letters I, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1999, c1963, 48:246. John, author of Revelation, had been exiled on the island of Patmos.

- ↑ 57.00 57.01 57.02 57.03 57.04 57.05 57.06 57.07 57.08 57.09 57.10 Schaff, Philip, History of the Christian Church, Vol VII, Ch IV.

- ↑ Martin Brecht and James F. Schaaf, Martin Luther, Fortress Press, 1993, p. 7. ISBN 0800628144.

- ↑ Martin Luther, "Let Your Sins Be Strong," a Letter From Luther to Melanchthon, August 1521, Project Wittenberg, retrieved October 1, 2006.

- ↑ Schaff, Philip, History of the Christian Church, Vol VII, Ch V.

- ↑ In a Greek letter to his friend Camerarius. The letter was published in the original Greek by W. Meyer, in the reports of the München Academy of Sciences, Nov. 4, 1876, pp. 601-604.The text is changed in the Corp. Reform ., I. 753. Melanchton calls Luther a very reckless man ( ἀνὴρ ὡς μάλιστα εὐχερής ), but hopes that he will become more solemn ( σεμνότερος).

- ↑ 62.0 62.1 Schaff, Philip. "Luther’s Marriage. 1525.", History of the Christian Church, Volume VII. Modern Christianity. The German Reformation. § 77.

- ↑ "Martin Luther", Encyclopaedia Britannica 1911.

- ↑ Jaroslav J. Pelikan, Hilton C. Oswald, Luther's Works, 55 vols. (St. Louis and Philadelphia: Concordia Pub. House and Fortress Press, 1955-1986), 46: 50-51.

- ↑ Ibid., 46: 47-55

- ↑ Luther, Martin. "Preface", Small Catechism.

- ↑ Luther, Martin. Luther's Works. Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1971, 50:172-173. The remark indicates that he saw himself as the mythological Saturn, who devoured his children; Luther wanted to get rid of many of his writings except for the two mentioned. The Large and Small Catechisms are spoken of as one work by Luther in this letter.

- ↑ Shaff, Philip. "Luther's Translation of the Bible", History of the Christian Church, New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910. Schaff quotes Hegel's Philosophie der Geschichte, p. 503: "Luther hat die Autorität der Kirche verworfen und an ihre Stelle die Bibel und das Zeugniss des menschlichen Geistes gesetzt. Dass nun die Bibel selbst die Grundlage der christlichen Kirche geworden ist, ist von der grössten Wichtigkeit; jeder soll sich nun selbst daraus belehren, jeder sein Gewissen daraus bestimmen können. Diess ist die ungeheure Veränderung im Principe: die ganze Tradition und das Gebäude der Kirche wird problematisch und das Princip der Autorität der Kirche umgestossen. Die Uebersetzung, welche Luther von der Bibel gemacht hat, ist von unschätzbarem Werthe für das deutsche Volk gewesen. Dieses hat dadurch ein Volksbuch erhalten, wie keine Nation der katholischen Welt ein solches hat; sie haben wohl eine Unzahl von Gebetbüchlein, aber kein Grundbuch zur Belehrung des Volks. Trotz dem hat man in neueren Zeiten Streit deshalb erhoben, ob es zweckmässig sei, dem Volke die Bibel indie Hand zu geben; die wenigen Nachtheile, die dieses hat, werden doch bei weitem von den ungeheuren Vortheilen überwogen; die äusserlichen Geschichten, die dem Herzen und Verstande anstössig sein können, weiss der religiöse Sinn sehr wohl zu unterscheiden, und sich an das Substantielle haltend überwindet er sie."

- ↑ Tyndale's New Testament, xv, xxvii.

- ↑ Tyndale's New Testament, ix–x.

- ↑ Schaff, Philip. History of the Christian Church, 8 vols., New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1910.

- ↑ A Christian Exhortation to the Livonians concerning Public Worship and Concord (June 17, 1525) in Luther's Works, 53:47. Translated from Weimar Ausgabe 18:417-421.

- ↑ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin", 73.

- ↑ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin", 74.

- ↑ Luther's Works, 37:223–224.

- ↑ This quotation leaves out this sentence: "There were two who then wrote me, with much more skill than Dr. Karlstadt has, and who did not torture the Word with their own preconceived notions." Cf. Luther's Works 40:68.

- ↑ Quoted in Heinrich Gelzer, Gustav Ferdinand Leopold König,The Life of Martin Luther, the German Reformer 1855, London, Nathaniel Cook, Milford House, Strand, p. 145. Philip Schaff gives the German: "Das bekenne ich," he wrote, December 15, 1524, to the Christians in Strassburg (De Wette, II. 577), "wo D. Carlstadt oder jemand anders vor fünf Jahren mich hätte mögen berichten, dass im Sacrament nichts denn Brot und Wein wäre, der hätte mir einen grossen Dienst gethan. Ich habe wohl so harte Anfechtungen da erlitten und mich gerungen und gewunden, dass ich gern heraus gewesen wäre, weil ich wohl sah, dass ich damit dem Papstthum hätte den grössten Puff können geben. Ich hab auch zween gehabt, die geschickter davon zu mir geschrieben haben denn D. Carlstadt, und nicht also die Worte gemartert nach eigenem Dünken. Aber ich bin gefangen, kann nicht heraus: der Text ist zu gewaltig da, und will sich mit Worten nicht lassen ans dem Sinn reissen." [2]; cf. Weimar Ausgabe 15:391-397 and Luther's Works 40:68.

- ↑ Schaff-Herzog, "Luther, Martin", 74.

- ↑ Stöhr, Martin. "Die Juden und Martin Luther," in Kremers, Heinz et al (eds.) Die Juden und Martin Luther; Martin Luther und die Juden. Neukirchener publishing house, Neukirchen Vluyn 1985, 1987 (second edition). p. 90. Taken from Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 109. See also Oberman, Heiko. Luther: Between Man and Devil. New Haven, 1989.

- ↑ Hsia, R. Po-chia. "Jews as Magicians in Reformation Germany," in Gilman, Sander L. and Katz, Steven T. Anti-Semitism in Times of Crisis, New York: New York University Press, 1991, pp. 119-120, cited in Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 109.

- ↑ Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 109.

- ↑ 82.0 82.1 Noble, Graham. "Martin Luther and German anti-Semitism," History Review (2002) No. 42:1-2.

- ↑ Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 110.

- ↑ Luther, Martin. On the Jews and their Lies, 154, 167, 229, cited in Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 111.

- ↑ Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 112.

- ↑ Obermann, Heiko. Luthers Werke. Erlangen 1854, 32:282, 298, in Grisar, Hartmann. Luther. St. Louis 1915, 4:286 and 5:406, cited in Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 113.

- ↑ Luther, Martin. "On the Jews and Their Lies," Luthers Werke. 47:268-271.

- ↑ Michael, Robert. "Luther, Luther Scholars, and the Jews," Encounter, 46 (Autumn 1985) No.4:343.

- ↑ Luther, Martin. On the Jews and Their Lies, cited in Michael, Robert. "Luther, Luther Scholars, and the Jews," Encounter 46 (Autumn 1985) No. 4:343-344.

- ↑ Marcus, Jacob Rader. The Jew in the Medieval World, p. 198, cited in Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 110.

- ↑ 91.0 91.1 91.2 Michael, Robert. Holy Hatred: Christianity, Antisemitism, and the Holocaust. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2006, p. 117.

- ↑ Vincent Fettmilch, a Calvinist, reprinted On the Jews and their Lies in 1612 to stir up hatred against the Jews of Frankfurt. Two years later, riots in Frankfurt saw the deaths of 3,000 Jews and the expulsion of the rest. Fettmilch was executed by the Lutheran city authorities, but Robert Michael writes that his execution was for attempting to overthrow the authorities, not for his offenses against the Jews.

- ↑ "The assertion that Luther's expressions of anti-Jewish sentiment have been of major and persistent influence in the centuries after the Reformation, and that there exists a continuity between Protestant anti-Judaism and modern racially oriented anti-Semitism, is at present wide-spread in the literature; since the Second World War it has understandably become the prevailing opinion." Johannes Wallmann, "The Reception of Luther's Writings on the Jews from the Reformation to the End of the 19th century", Lutheran Quarterly, n.s. 1 (Spring 1987) 1:72-97.

- ↑ For similar views, see:

- Berger, Ronald. Fathoming the Holocaust: A Social Problems Approach (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 2002), 28.

- Rose, Paul Lawrence. "Revolutionary Antisemitism in Germany from Kant to Wagner," (Princeton University Press, 1990), quoted in Berger, 28);

- Shirer, William. The Rise and Fall of the Third Reich, (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1960).

- Johnson, Paul. A History of the Jews (New York: HarperCollins Publishers, 1987), 242.

- Poliakov, Leon. History of Anti-Semitism: From the Time of Christ to the Court Jews. (N.P.: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2003), 216.

- Berenbaum, Michael. The World Must Know. (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press and the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 1993, 2000), 8–9.

- ↑ Grunberger, Richard. The 12-Year Reich: A Social History of Nazi German 1933-1945 (NP:Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1971), 465.

- ↑ Himmler wrote: "what Luther said and wrote about the Jews. No judgment could be sharper."

- ↑ Ellis, Marc H. Hitler and the Holocaust, Christian Anti-Semitism", (NP: Baylor University Center for American and Jewish Studies, Spring 2004), Slide 14. [3]

- ↑ Brecht 3:351.

- ↑ Johannes Wallmann, "The Reception of Luther's Writings on the Jews from the Reformation to the End of the 19th century", Lutheran Quarterly, n.s. 1 (Spring 1987) 1:72-97.

- ↑ Siemon-Netto, The Fabricated Luther, 17-20.

- ↑ Siemon-Netto, "Luther and the Jews," Lutheran Witness 123 (2004) No. 4:19, 21.

- ↑ Hillerbrand, Hans J. "Martin Luther," Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2007. Hillerbrand writes: "His strident pronouncements against the Jews, especially toward the end of his life, have raised the question of whether Luther significantly encouraged the development of German anti-Semitism. Although many scholars have taken this view, this perspective puts far too much emphasis on Luther and not enough on the larger peculiarities of German history."

- ↑ For similar views, see:

- Bainton, Roland, 297;

- Briese, Russell. "Martin Luther and the Jews," Lutheran Forum (Summer 2000):32;

- Brecht, Martin Luther, 3:351;

- Edwards, Mark U. Jr. Luther's Last Battles: Politics and Polemics 1531-46. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1983, 139;

- Gritsch, Eric. "Was Luther Anti-Semitic?", Christian History, No. 3:39, 12.;

- Kittelson, James M., Luther the Reformer, 274;

- Marius, Richard. Martin Luther, 377;

- Oberman, Heiko. The Roots of Anti-Semitism: In the Age of Renaissance and Reformation. Philadelphia: Fortress, 1984, 102;

- Rupp, Gordon. Martin Luther, 75;

- Siemon-Netto, Uwe. Lutheran Witness, 19.

- ↑ Berger, Ronald. Fathoming the Holocaust: A Social Problems Approach (New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 2002), 28.

- ↑ Rose, Paul Lawrence. Revolutionary Antisemitism in Germany from Kant to Wagner. Princeton University Press, 1990. Cited in Berger, Ronald. Fathoming the Holocaust: A Social Problems Approach. New York: Aldine De Gruyter, 2002, 28.

- ↑ Iversen OH (1996). "[Martin Luther's somatic diseases. A short life-history 450 years after his death]" (in Norwegian). Tidsskr. Nor. Laegeforen. 116 (30): 3643–6. PMID 9019884.

- ↑ Edwards, 9.

- ↑ Spitz, 354.

- ↑ Luther, Martin. Sermon No. 8, "Predigt über Mat. 11:25, Eisleben gehalten," February 15, 1546, Luthers Werke, Weimar 1914, 51:196-197.

- ↑ Poliakov, Léon. From the Time of Christ to the Court Jews, Vanguard Press, p. 220.

- ↑ Mackinnon, James. Luther and the Reformation. Vol. IV, (New York: Russell & Russell, 1962, p. 204.

- ↑ Luther, Martin. Admonition against the Jews, added to his final sermon, cited in Oberman, Heiko. Luther: Man Between God and the Devil, New York: Image Books, 1989, p. 294.

- ↑ Oberman, Heiko, Luther: Man Between God and the Devil. New York; Doubleday, 1990, 3-4

- ↑ Brecht, Martin. Martin Luther. tr. James L. Schaaf, Philadelphia: Fortress Press, 1985–93, 3:369-379.

- ↑ Kellermann, James A. (translator) "The Last Written Words of Luther: Holy Ponderings of the Reverend Father Doctor Martin Luther". February 16, 1546.

- ↑ Original German and Latin of Luther's last written words is: "Wir sein pettler. Hoc est verum." Heinrich Bornkamm, Luther's World of Thought, tr. Martin H. Bertram (St. Louis: Concordia Publishing House, 1958), 291.

- ↑ Dorman, Ted. Review of "Union With Christ: The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther". First Things, 1999. Retrieved 2007-05-31.

- ↑ Tuomo Mannermaa, "Why Is Luther So Fascinating? Modern Finnish Luther Research," Union with Christ, (Grand Rapids: Eerdmans, 1998), 1.

- ↑ William Wallace Schumacher, "'Who Do I Say That You Are?' Anthropology and the Theology of Theosis in the Finnish School of Tuomo Mannermaa" (Ph.D. diss., Concordia Seminary, St. Louis, Missouri, 2003), 260 et passim. Cf. also the papers that constitute Union with Christ: The New Finnish Interpretation of Luther by various authors; cf. also Robert Kolb and Charles P. Arand, The Genius of Luther's Theology: A Wittenberg Way of Thinking for the Contemporary Church, (Grand Rapids, Michigan: Baker Academic, 2008), 48: "These views ignore the radically different metaphysical base of Luther's understanding and that of the Eastern church, and they ignore Luther's understanding of the dynamic, re-creative nature of God's Word."

- ↑ Jaroslav Pelikan and Helmut T. Lehmann, general editors, Luther's Works, 55 vols., (CPH: St. Louis, AF: Minneapolis, 1955-1986), 1:v.

- ↑ Jaroslav Pelikan and Helmut T. Lehmann, general editors, Luther's Works, 55 vols., (CPH: St. Louis, AF: Minneapolis, 1955-1986), 47:136, 137-306.

- ↑ Falk, Gerhard, The Jew in Christian Theology: Martin Luther's Anti-Jewish Vom Schem Hamphoras, Previously Unpublished in English, and Other Milestones in Church Doctrine Concerning Judaism, McFarland: Jefferson, NC, 1992. ISBN 0899507166.

- ↑ Jaroslav Pelikan and Helmut T. Lehmann, general editors, Luther's Works, 55 vols., (CPH: St. Louis, AF: Minneapolis, 1955-1986), 41:257-376.

- ↑ "Martin Luther", Onlineliterature.com, accessed May 2007.

- ↑ Luther, The Catholic Encyclopedia, Vol. 9, 1913.

- ↑ Jaroslav Pelikan and Helmut T. Lehmann, general editors, Luther's Works, 55 vols., (CPH: St. Louis, AF: Minneapolis, 1955-1986), 41:179-255.

- ↑ Edwards, Mar U. "Luther's Last Battles", Concordia Theological Quarterly, Vol. 48, Nos. 2 & 3, April-July 1984.

Further reading

For works by and about Luther, see Martin Luther (resources).

|

|||||||||||||

| Persondata | |

|---|---|

| NAME | Luther, Martin |

| ALTERNATIVE NAMES | |

| SHORT DESCRIPTION | German theologian and priest |

| DATE OF BIRTH | November 10, 1483 |

| PLACE OF BIRTH | Eisleben, Germany |

| DATE OF DEATH | February 18, 1546 |

| PLACE OF DEATH | Eisleben, Germany |