Macedonia (terminology)

| Macedonia | |

|

|

| The contemporary geographical region of Macedonia is not officially defined by any international organisation or state. In some contexts it appears to span five current sovereign countries: Albania, Bulgaria, Greece, the Republic of Macedonia, and Serbia. For more details see the boundaries and definitions section in Macedonia (region). |

The definition of Macedonia is a major source of confusion and debate due to the overlapping use of the term to describe geographical, political and historical areas, languages and peoples. Ethnic groups inhabiting the area use different terminology for the same entity, or the same terminology for different entities, which is often confusing to other inhabitants of the region and foreigners alike.

Historically, the region has presented markedly shifting borders across the Balkan peninsula. Geographically, no single definition of its borders or the names of its subdivisions is accepted by all scholars and ethnic groups. Demographically, it is mainly inhabited by four ethnic groups, three of which self-identify as Macedonians: two, a Bulgarian[1] and a Greek one at a regional level, while a third ethnic Macedonian one at a national level. Linguistically, the names and origins of the languages and dialects spoken in the region are a source of controversy. Politically, the rights to the extent of the use of the name Macedonia and its derivatives has led to a diplomatic dispute between Greece and the Republic of Macedonia. Despite mediation of the United Nations, the dispute is still pending resolution.

Contents |

Etymology

There are a number of theories regarding the etymology of the name "Macedonia". According to ancient Greek mythology, Makednos was a grandson of Deucalion and son to Aeolus(Hesiod) or a grandson of Hellen (Hellanicus). He gave his name to the tribes of the Macedonians, a group of tribes that occupied and settled parts of what is nowadays considered western, southern and central Macedonia and founded the kingdoms of Macedon.

Homer uses the adjective μακεδνός makednós, translated as "tall", to describe a poplar tree,[2] and which the grammarian Hesychius of Alexandria records as a Doric word meaning "large" or "heavenly".[3] It has been suggested that both the Macedonians (Makedónes) and their Makednoí tribal ancestors were regarded as tall people, hence their name.[4]

According to Herodotus, the Makednoí were a Hellenic tribe that occupied and settled the country that they named Macedonia. Those Macedonians that still chose to migrate south and later invaded Peloponnesus were renamed to Dorians,[5] one of the principal ancient Greek tribes.

Another plausible translation of the adjective "makednos" would be high. According to the World Book Encyclopedia, the Macedonians may have acquired their name because of their mountainous origin. The Online Etymology Dictionary quoting Ernest Klein's etymological dictionary[6] summarizes these theories as:

From Gk. Makedones, lit. "highlanders" or "the tall ones," related to makednos "long, tall," makros "long, large".[7]

There would appear to be a synonymy among the names of different tribes living in the region, since a likely interpretation of the names of the Dorians and the Bryges also is "highlanders". All the previous names are considered to be of Indo-European origin, the root of makednos being *māk-, "long, thin", which becomes "long, large" in Greek.[8] The syllables beyond *māk- are not a compound resulting from the process of production, but are an inherited extension of unknown prehistoric origin; in this case, *-dno-[9]. (Note: the asterisk before a word indicates that it is a hypothetical construction, not an attested form)

History

| Historical Macedonia | |

|

|

| Ancient Macedon | Roman Province |

|

|

| Byzantine province (approximate borders) |

Ottoman period (approximate) |

| "If it were not confusing, it would not have been Macedonia." [10] | |

| Ancient Macedon: Approximate borders of the kingdom before expansion to conquer the whole known world, according to archaeological findings and historic references. c.350 BC Roman province: Macedonia occupied areas outside the contemporary geographical area to the West (approximate borders of maximum extent). There was also a late antique diocese of Macedonia. Byzantine province: Macedonia excluded Thessaloniki and occupied only the Eastern part of the contemporary geographical area (approximate borders). Ottoman period: During the first four centuries of the Ottoman period, western scholars thought of Macedonia in terms of Greco-Roman geography.[11] The Ottoman Empire did not have an administrative unit by that name.[11] In the early 19th century, the definition of Macedonia by most scholars, approximately matched the contemporary region, with occasional farther variations.[11] |

|

The region of Macedonia has been home or a part to several historical political entities, even before the invasion of the Macedonians from the south, as is attested by Herodot; Many non-Hellenic tribes occupied its lands before and after the formation of the first Macedonian kingdoms. The borders of each of these entities were different as well as those of any kingdom or province that through the ages shared this name. The area occupied by ancient Macedon, the kingdom formed by the Argead Macedonians, at its greatest extent, approximately coincided with contemporary Macedonia in Greece.[12]

Early history

- Main articles: History of the region of Macedonia and Macedon

A common misconception about the ancient Macedonians is the fact that they were but a single tribe. They actually comprised a number of tribes, each with its own king and ruling class. What was called kingdom of Macedon was actually the lands occupied by one of these tribes, the Argeads and ruled by the most famous Macedonian kings, the Temenids. These eventually achieved dominance over most Macedonian kingdoms with Philip II and his heir Alexander III. Until then, the Argeads' rule did not usually incorporate upland areas, like Lyncestis. Under Philip II of Macedon, Macedonia expanded markedly, growing to include Chalcidice, parts of Thrace, most Macedonian kingdoms and tribute was extracted by many of the barbarians of the north, like the Paeones and the Agrianes; Philip managed to achieve hegemony over Hellas and was hailed as General of all Greece. After his assassination, his son Alexander the Great led his armies into the vast Persian Empire and Macedon, within a few decades, expanded to an Empire, occupying a huge stretch of lands including the Balcan peninsula up and beyond Istros, the Greek name of the river Danube, the Asian dominions of the Achemenids, Egypt and parts of India and Arabia Deserta. After his death, his empire was contested by his generals and after long wars it was divided into kingdoms that lasted for centuries, initiating what is called the Hellenistic era. Of these kingdoms, Macedonia was not the largest nor the most powerful. After the Roman conquest following the Macedonian Wars, the Roman Senate established a province of Macedonia, which, through the centuries, comprised different lands. Under the Byzantines, the theme of Macedonia was much further to the east, in what would in the past be called Thrace, excluding even Thessalonica. The Ottoman Empire did not include an administrative region by the name of Macedonia.

There have been various political entities which have used the name Macedonia. Macedon, the ancient kingdom, existed in the northernmost part of ancient Greece, bordering the kingdom of Epirus on the west and the region of Thrace to the east. The first Macedonian state emerged in the 8th or early 7th century BCE. Prior to his death in 323 BCE, the Macedon kingdom's most notable ruler Alexander the Great conquered most of the land in southwestern Asia stretching from what is currently Turkey in the west to parts of India in the east. The kingdom lasted until the Romans divided it into four republics in 168 BCE.[13]

The ancient Romans had two different entities called Macedonia, at different levels. Macedonia was established as a Roman province in 146 BC Its boundaries were shifted from time to time for administrative convenience, but it usually extended west to the Adriatic. Diocletian divided it into Macedonia prima and Macedonia salutaris. Macedonia, was a late Roman diocese, organized some time around 300; authorities differ, but it certainly existed under Constantine. In addition to the two Macedonian provinces, it included Epirus vetus, Epirus nova, Thessaly, Achaea, and Crete - almost all of modern Greece and the present Republic, as well as much of Albania. Both the diocese and the provinces ceased to function as administrative units when the late Roman Empire lost control of the Balkans around 600 or 700.

During the Byzantine period, Macedonia was a theme organised by Empress Irene, out of the Theme of Strymon, stretching of Adrianople and the Evros valley east along the Sea of Marmara (ancient Macedon was the Theme of Thessalonica). John I Tzimisces replaced this with a ducate of Adrianople, which included much of his Bulgarian conquests. Themes were not named geographically and the the original sense was "army". They became districts during the military and fiscal crisis of the seventh century, when the Byzantine armies were instructed to find their supplies from the locals, wherever they happened to be. Thus the Armeniac theme was considerably west of Armenia; the Thracesian theme was in Asia Minor, not in Thrace.[14] The Macedonian dynasty of the Byzantine Empire acquired its name from its founder, Basil I the Macedonian; he was born in this theme of Macedonia. His ancestry is disputed; contemporary accounts call him an Armenian by descent.

The Ottomans held Macedonia for five centuries; they did not keep Macedonia as an administrative unit. The region of European Turkey lying between Thessaly and Serbia continued to be called Macedonia, however. In 1904, when most of it was placed under international administration, it contained the districts of Salonica, Monastir, Üsküb, Kossovo, Drama, and Serres. In 1912–3, this was divided among the Balkan states.[15][16][17][18]

The ancient Christian sect, the Macedonians, derived their name from their founder, Bishop Macedonius I of Constantinople, not from any political or geographical region of Macedonia.

Modern history

Since the early stages of the Greek Revolution, the provisional government of Greece claimed Macedonia as part of Greek national territory, but the Treaty of Constantinople (1832), which established a Greek independent state, set its northern boundary between Arta and Volos.[19] When the Ottoman Empire started breaking apart, Macedonia was claimed by all members of the Balkan League (Serbia, Montenegro, Greece and Bulgaria), and by Romania. Under the Treaty of San Stefano that ended the Russo-Turkish War, 1877–78 the entire region, except Thessaloniki, was included in the borders of Bulgaria, but after the Congress of Berlin in 1878 the region was returned to the Ottoman Empire. The armies of the Balkan League advanced and occupied Macedonia in the First Balkan War in 1912. Because of disagreements between the allies about the partition of the region, the Second Balkan War erupted, and in its aftermath the arbitrary region of Macedonia was split into various entities.

Macedonia (as a region of Greece) refers to a region of three peripheries in northern Greece, incorporated in 1913, as a result of the Balkan Wars, between the Ottoman Empire and the Balkan League.[20]

Macedonia (as a People's Republic within Yugoslavia) used to refer to the People's Republic of Macedonia established in 1946, later known as the Socialist Republic of Macedonia, one of the constituent republics of the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, renamed in 1963.[21]

Macedonia (as a contemporary sovereign state) refersN-[3] to the conventional short form name of the Republic of Macedonia, which held a referendum and established its independence from Yugoslavia on September 8, 1991.[22]

Geography

Macedonia (as a current geographical term) refers to a region of the Balkan peninsula in south-eastern Europe, covering some 60,000 or 70,000 square kilometers. Although the region's borders are not officially defined by any international organization or state, in some contexts, the territory appears to correspond to the basins of (from west to east) the Haliacmon (Aliákmonas), Vardar / Axios and Struma / Strymónas rivers, and the plains around Thessaloniki and Serres.

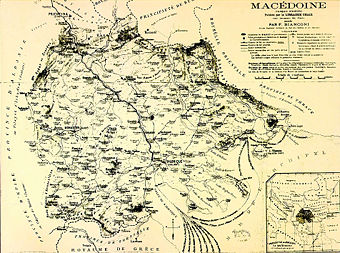

In a historic context, the term Macedonia was used in various ways. Macedonia was not an administrative division of the Ottoman Empire at any time during the five or six centuries it occupied Europe.[10] The geographer H.R. Wilkinson suggests that the region "defies definition" but that many mappers agree "on its general location".[11] Macedonia was well enough defined in 1897 for Gladstone to propose "Macedonia for the Macedonians", implying all the inhabitants of the region, irrespective of their ethnicity.[23] The Balkan nations began to proclaim their rights to it after the Treaty of San Stefano in 1878 and its revision at the Congress of Berlin.

Many ethnographic maps were produced in this period of controversy; these differ primarily in the areas given to each nationality within Macedonia. This was in part a result of the choice of definition: an inhabitant of Macedonia might well have different nationalities depending on whether the basis of classification was denomination, descent, language, self-identification or personal choice. In addition, the Ottoman census, taken on the basis of religion, was misquoted by all sides; descent, or "race", was largely conjectural; inhabitants of Macedonia might speak a different language at the market and at home, and the same Slavic dialect might be called Serbian "with Bulgarian influences", Macedonian, or West-Bulgarian.

These maps would also differ somewhat in the boundaries given to Macedonia. Its only inarguable limits were the Aegean Sea and the Serbian and Bulgarian frontiers (as of 1885); where it bordered on Old Serbia, Albania, and Thrace (all parts of Ottoman Rumelia) was debatable.[11]

The Greek ethnographer Nicolaides, the Austrian Meinhard, and the Bulgarian Kǎnčev placed the northern boundary of Macedonia at the Šar Mountains and the Crna hills, as had scholars before 1878.[11] The Serb Gopčevič preferred a line much further south, assigning the entire region from Skopje to Strumica to "Old Serbia"; and some later Greek geographers have agreed to a more restricted Macedonia.[11] In addition, maps might vary in smaller details: as to whether this town or that was Macedonian. One Italian map included Prizren, where Nicolaides and Meinhard had drawn the boundary just south of it. On the south and west, Grevena, Korçë, and Konitsa varied from map to map; on the east, the usual line is the lower Mesta / Nestos river and then north or northwest, but one German geographer takes the line so far west as to exclude Bansko and Nevrokop / Gotse Delchev.[11]

Subregions

| Geographical Macedonia | |

|

|

|

Major sub-regions: |

|

|

Minor parts: |

The region of Macedonia is commonly divided into three major and two minor sub-regions.[24] The name Macedonia appears under certain contexts on the major regions, while the smaller ones are traditionally referred to by other local toponyms:

Major regions

The region of Macedonia is commonly split geographically into three main sub-regions, especially when discussing the Macedonian Question. The terms are used in non-partisan scholarly works, although they are also used in ethnic Macedonian literature of an irredentist nature.[25]

Aegean MacedoniaN-[1] (or Greek Macedonia) is a term that refers to an area in the south of the Macedonia region. The borders of the area are, overall, those of ancient Macedonia in Greece. It covers an area of 34,200 km²[26] (for discussion of the reported irredentist origin of this term, see Aegean Macedonia).

Pirin MacedoniaN-[2] (or Bulgarian Macedonia) is an area in the east of the Macedonia region. The borders of the area approximately coincide with those of Blagoevgrad Province in Bulgaria.[24] It covers an area of 6,449 km².[27]

Vardar Macedonia (formerly Yugoslav Macedonia) is an area in the north of the Macedonia region. The borders of the area are those of the Republic of Macedonia.[24] It covers an area of 25,333 km².[28]

Minor regions

In addition to the above named sub-regions, there are also two smaller regions, in Albania and Serbia respectively. These regions are also considered geographically part of Macedonia. They are referred to by ethnic Macedonians as follows,[25] but typically aren't referred to by non-partisan scholars.

Mala Prespa and Golo Bardo is a small area in the west of the Macedonia region in Albania, mainly around the Lake Ohrid. It includes parts of the Korçë, Pogradec and Devoll districts. These districts in whole occupy about 3,000 km², but the area concerned is significantly smaller.

Gora and Prohor Pchinski are minor parts in the north of the Macedonia region in Serbia. They roughly correspond to the Serbian municipality of Dragaš (435 km²) and the monastery of Prohor Pčinjski.

Demographics

The region, as defined above, has a total population of about 5 million. The main disambiguation issue in demographics is the self-identifying name of two contemporary groups. The ethnic Macedonian population of the Republic of Macedonia self-identify as Macedonian on a national level, while the Greek Macedonians self-identify as both Macedonian on a regional, and Greek on a national level. According to the Greek arguments, the ancient Macedonians' nationality was Greek and thus, the use of the term on a national level lays claims to their history. This disambiguation problem has led to a wide variety of terms used to refer to the separate groups, more information of which can be found in the terminology by group section.

| Demographic Macedonia | |

| Macedonians c. 5 million |

All inhabitants of the region, irrespective of ethnicity |

| MacedoniansN-[3] c. 1.3 million plus diaspora |

A contemporary ethnic group, also referred to as Slavomacedonians or Macedonian Slavs[29], N-[5] |

| MacedoniansN-[3] c. 2.0 million |

Citizens of the Republic of Macedonia irrespective of ethnicity |

| Macedonians c. 2.6 million plus diaspora |

A Ethnic Greek regional group, also referred to as Greek Macedonians |

| Macedonians (unknown population) |

A group of antiquity, also referred to as Ancient Macedonians. |

| Macedonians c. 0.3 million |

A Bulgarian regional group,[30] also referred to as Piriners. |

| Macedo-Romanians c. 0.3 million |

An alternative name for Aromanians |

The self-identifying Macedonians (collectively referring to the inhabitants of the region) that inhabit or inhabited the area are:

As an ethnic group, Macedonians refersN-[3] to the majority (64.7%, 2002) of the population of the Republic of Macedonia. Statistics for 2002 indicate the population of ethnic Macedonians within Republic of Macedonia as 1,297,981.[28][31] On the other hand, as a legal term, it refers to all the citizens of the Republic of Macedonia, irrespective of their ethnic or religious affiliation.[28] However, the preamble of the constitution[22] distinguishes between "the Macedonian people" and the "Albanians, Turks, Vlachs, Romanics and other nationalities living in the Republic of Macedonia", but for whom "full equality as citizens" is provided. As of 2002 the total population of the country is 2,022,547.[31]

As a regional group in Greece, Macedonians refers to ethnic Greeks (98%, 2001) living in regions referred to as Macedonia, and particularly Greek Macedonia. This group composes the vast majority of the population of the Greek region of Macedonia. The 2001 census for the total population of the Macedonia region in Greece shows 2,625,681.[32]

The same term in antiquity described the inhabitants of the kingdom of Macedon,[23] including their notable rulers Philip II of Macedon and Alexander the Great who self-identified as Greeks.[33]

As a regional group in Bulgaria, Macedonians refers to the inhabitants of Bulgarian Macedonia, who in their vast majority self-identify as Bulgarians at a national level and as Macedonians at a regional, but not ethnic level.[30] As of 2001, the total population of Bulgarian Macedonia is 341,245, while the ethnic Macedonians living in the same region are 3,117.[34] The Bulgarian Macedonians also self-identify as Piriners (пиринци, pirintsi)[35] to avoid confusion with the neighboring ethnic group.

Macedo-Romanians can be used as an alternative name for Aromanians, people living throughout the southern Balkans, especially in northern Greece, Albania, the Republic of Macedonia and Bulgaria, and as an emigrant community in Northern Dobruja, Romania. According to Ethnologue, their total population in all countries is 306,237.[36] This not very frequent appellation is the only one with the disambiguating portmanteau, both within the members of the same ethnic group and the other ethnic groups in the area.[37] To make matters more confusing, Aromanians are often called "Machedoni" by Romanians, as opposed to the citizens of Macedonia, who are called "Macedoneni".

The ethnic Albanians living in the region of Macedonia, as defined above, are mainly concentrated in the Republic of Macedonia (especially in the northwestern part that borders Kosovo and Albania), and less in the Albanian minor sub-region of Macedonia around the Lake Ohrid. As of 2002, the total population of Albanians within the republic is 509,083 or 25.2% of the country's total population.[31]

Linguistics

As language is one of the elements tied in with national identity, the same disputes that are voiced over demographics are also found in linguistics. There are two main disputes about the use of the word Macedonian to describe a linguistic phenomenon, be it a language or a dialect:

| Linguistic Macedonia | |

| MacedonianN-[3] | A contemporary Slavic language, also referred to as Slavomacedonian or Macedonian Slavic[38][39][40], N-[5] |

| Macedonian | A dialect of Modern Greek, typically simply referred to as Greek, since its differences with the Greek spoken in the rest of Greece are only a few words, phrases and a deeper accent. |

| Macedonian | A language or dialect of antiquity, possibly a dialect of ancient Greek |

| Macedo-Romanian | Another name for the Aromanian language |

The origins of the Ancient Macedonian language are currently debated. At this time it is not conclusively determined whether the language / dialect was a Greek dialect related to Doric Greek[41][42] and/or Aeolic Greek[43] dialects among others, a sibling language of ancient Greek forming a Hellenic[44] (i.e. Greco-Macedonian) supergroup, or viewed as an Indo-European language which is a close cousin to Greek and also somewhat related to Thracian and Phrygian languages.[45] The scientific community generally agrees that, although sources are available (e.g. Hesychius' lexicon, Pella curse tablet)[46] there is no decisive evidence to exclude any of the above hypothesis.[47]

The (south Slavic) Macedonian languageN-[3] is unrelated to the Ancient Macedonian language. It is currently the subject of two major disputes. The first is over the name (alternative ways of referring to this language can be found in the terminology by group section and in the article Macedonian language naming dispute). The second dispute is over the existence of a Macedonian language distinct from Bulgarian, the denial of which is a position supported by nationalist groups,[48], Bulgarian and other linguists and also by many ordinary Bulgarians. Further information on this can be found in the Macedonian language article.

Macedonian is also the name of a dialect of Modern Greek, a language of the Indo-European family. Additionally, Macedo-Romanian is an Eastern Romance language, spoken in Southeastern Europe by the Aromanians.[37]

Politics

- See also: Macedonia naming dispute

The controversies in geographic, linguistic and demographic terms, are also manifested in international politics. Among the autonomous countries that were formed as a result of the break up of Yugoslavia in the 1990s, was the (until then) subnational entity of SFRJ, by the official name of Socialist Republic of Macedonia, the others being Serbia, Slovenia, Croatia, Bosnia and Herzegovina and Montenegro. The peaceful break-away of that nation resulted in a necessary change for its name, to signify disassociation from federal Yugoslavia.

| Political Macedonia | |

|

|

| Μακεδονία (Macedonia) (Macedonia in Greece) |

|

|

|

| Македонија (Macedonia) (Republic of Macedonia) |

|

Republic of MacedoniaN-[3] is the constitutional name[22] of the sovereign state which occupies the northern part of the geographical region of Macedonia, which roughly coincides with the geographic subregion of Vardar Macedonia. The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) is a term used to refer to this state by the main international organisations, including United Nations,[49] European Union,[50] NATO,[51] IMF,[52] WTO,[53] IOC,[54] World Bank,[55] EBRD,[56] OSCE,[57] FIFA,[58] and FIBA.[59] The term was introduced in 1993 by the United Nations, following a naming dispute with Greece. Some countries use this term as a stop-gap measure, pending resolution of the naming dispute.[60]

Greece and the Republic of Macedonia each consider this name a compromise:[61] it is opposed by some Greeks for containing the Greek self-identifying name Macedonia, and by many in the Republic of Macedonia for not being the short self-identifying name.[62] Greece uses it in both the abbreviated (FYROM or ΠΓΔΜ)N- and spellout form (πρώην Γιουγκοσλαβική Δημοκρατία της Μακεδονίας).

Macedonia refers also to a geographic region in Greece, which roughly coincides with the southernmost major geographic subregion of Macedonia. It is divided in the three administrative sub-regions (peripheries) of West, Central, and East Macedonia. The region is overseen by the Ministry for Macedonia–Thrace. The capital of Greek Macedonia is Thessaloniki, which is the largest city in the region of Macedonia. Thessaloniki is also the joint capital city ("συμπρωτεύουσα"-symprotévousa)[63] of Greece, the capital being Athens.

Ethnic Macedonian nationalism

Extremist ethnic Macedonian nationalists of the "United Macedonia" movement have expressed irredentist claims to what they refer to as "Aegean Macedonia" (in Greece),[64][65][66] "Pirin Macedonia" (in Bulgaria),[67] "Mala Prespa and Golo Bardo" (in Albania),[68] and "Gora and Prohor Pchinski" (in Serbia).[69] Greek Macedonians, Bulgarians, Albanians and Serbs form the overwhelming majority of the population of each part of the region respectively.

Loring M. Danforth, a professor of anthropology working at Bates College in the United States who has written many award winning books and articles on Republic of Macedonia, Greece, Australia and nationalism, reports:

Extreme Macedonian nationalists, who are concerned with demonstrating the continuity between ancient and modern Macedonians, deny that they are Slavs and claim to be the direct descendants of Alexander the Great and the ancient Macedonians. The more moderate [ethnic] Macedonian position, generally adopted by better educated Macedonians and publicly endorsed by Kiro Gligorov, the first president of the newly independent Republic of Macedonia, is that modern Macedonians have no relation to Alexander the Great, but are a Slavic people whose ancestors arrived in Macedonia in the sixth century AD. Proponents of both the extreme and the moderate Macedonian positions stress that the ancient Macedonians were a distinct non-Greek people.

In addition to affirming the existence of the Macedonian nation, Macedonians are concerned with affirming the existence of a unique Macedonian language as well. While acknowledging the similarities between Macedonian and other South Slavic languages, they point to the distinctions that set it apart as a separate language. They also emphasize that although standard literary Macedonian was only formally created and recognized in 1944, the Macedonian language has a history of over a thousand years dating back to the Old Church Slavonic used by Sts. Cyril and Methodius in the ninth century.

Although all Macedonians agree that Macedonian minorities exist in Bulgaria and Greece and that these minorities have been subjected to harsh policies of forced assimilation, there are two different positions with regard to what their future should be. The goal of more extreme Macedonian nationalists is to create a "free, united, and independent Macedonia" by "liberating" the parts of Macedonia "temporarily occupied" by Bulgaria and Greece. More moderate Macedonian nationalists recognize the inviolability of the Bulgarian and Greek borders and explicitly renounce any territorial claims against the two countries. They do, however, demand that Bulgaria and Greece recognize the existence of Macedonian minorities in their countries and grant them the basic human rights they deserve.[70]

Schoolbooks and official government publications in the Republic have shown the country as part of an "unliberated" whole,[71][72][73][74][75][76][77][78] although the constitution of the Republic, especially after its amendment in 1995, does not include any territorial claims.[22][61]

Greek nationalism

Professor Danforth describes the Greek position on Macedonia as follows:

According to the Greek nationalist position on the Macedonian Question, because Alexander the Great and the ancient Macedonians were Greeks, and because ancient and modern Greece are bound in an unbroken line of racial and cultural continuity, it is only Greeks who have the right to identify themselves as Macedonians, not the Slavs of southern Yugoslavia, who settled in Macedonia in the sixth century AD and who called themselves "Bulgarians" until 1944. Greeks, therefore, generally refer to Macedonians as "Skopians", (from Skopje, the capital of the Republic of Macedonia) a practice comparable to calling Greeks "Athenians." The negation of Macedonian identity in Greek nationalist ideology focuses on three main points: the existence of a Macedonian nation, a Macedonian language, and a Macedonian minority in Greece. From the Greek nationalist perspective there cannot be a Macedonian nation since there has never been an independent Macedonian state: the Macedonian nation is an "artificial creation", an "invention", of Tito, who "baptized" a "mosaic of nationalities" with the Greek name "Macedonians".

Similarly Greek nationalists claim that because the language spoken by the ancient Macedonians was Greek, the Slavic language spoken by the "Skopians" cannot be called "the Macedonian language." Greek sources generally refer to it as "the linguistic idiom of Skopje" and describe it as a corrupt and impoverished dialect of Bulgarian. Finally, the Greek government denies the existence of a Macedonian minority in northern Greece, claiming that there exists only a small group of "Slavophone Hellenes" or "bilingual Greeks", who speak Greek and "a local Slavic dialect" but have a "Greek national consciousness".

From the Greek nationalist perspective, then, the use of the name "Macedonian" by the "Slavs of Skopje" constitutes a "felony", an "act of plagiarism" against the Greek people. By calling themselves "Macedonians" the Slavs are "stealing" a Greek name; they are "embezzling" Greek cultural heritage; they are "falsifying" Greek history. As Evangelos Kofos, a historian employed by the Greek Foreign Ministry told a foreign reporter, "It is as if a robber came into my house and stole my most precious jewels - my history, my culture, my identity". Greek fears that use of the name "Macedonia" by Slavs will inevitably lead to the assertion of irredentist claims to territory in Greek Macedonia are heightened by fairly recent historical events. During World War II Bulgaria occupied portions of northern Greece, while one of the specific goals of the founders of the People's Republic of Macedonia in 1944 was "the unification of the entire Macedonian nation", to be achieved by "the liberation of the other two segments" of Macedonia.[70]

Demetrius Andreas M.-A. Floudas, of Hughes Hall, Cambridge, a leading commentator on the naming dispute from the Greek side, sums up the reaction thus:

Skopje was accused of usurping the historical and cultural patrimony of Hellas in order to furnish a nucleus of national self-esteem for the new state and provide its citizens with a new, distinct, non-Bulgarian, non-Serbian, non-Albanian identity. FYROM emerges thus to Greek eyes as a country with a personality crisis, a nondescript parasitic state that lives off the historical grandeur of its neighbours, because it lacks an illustrious past of its own, for the sake of achieving cohesion for the unhomogeneous little new nation.

What appeared to go unquestioned in Greece nevertheless was whether there was indeed substance in the claims of FYROM that their citizens do feel members of a distinct 'Macedonian' nationality. To answer this appropriately, neither the decades of persistent indoctrination [during Tito's time] should be left out of consideration, nor Greece's violent struggle since 1991 in contrast to her complacency for the 45 years before this. If it was a common bond that the people in Skopje wanted, they found it by claiming this name and rallying the whole population in a united resistance front under a common cause against pugnacious Greece. After this bitter and protracted struggle, even the ones in FYROM who might have not initially been infused with any distinct Macedonian ethnic identity must be feeling very Macedonian now, thanks to Greece[79]

As of early 2008, the official position of Greece, adopted unanimously by the four largest political parties, has made a more moderate shift towards accepting a "composite name solution" (i.e. the use of the name "Macedonia" plus some qualifier), so as to disambiguate the former Yugoslav Republic from the Greek region of Macedonia and the wider geographic region of the same name.[80][81][82]

Names in the languages of the region

Macedonia

| Albanian: | Maqedonia | Greek: | Μακεδονία (Makedonia) | Russian: | Македония (Makedoniya) | ||

| Armenian: | Մակեդոնիա (Makedonia) | Ladino: | Makedonia, מקדוניה | Serbian: | Македонија, Makedonija | ||

| Aromanian: | Machidunia/Machedonia | Macedonian: | Македонија (Makedonija) | Turkish: | Makedonya | ||

| Bulgarian: | Македония (Makedoniya) | Romany: | Makedoniya | Ukrainian: | Македонія (Makedoniya) |

Terminology by group

All these controversies have led ethnic groups in Macedonia to use terms in conflicting ways. Despite the fact that these terms may not always be used in a pejorative way, they may be perceived as such by the receiving ethnic group. Both Greeks and ethnic Macedonians generally use all terms deriving from Macedonia to describe their own regional or ethnic group, and have devised several other terms to disambiguate the other side, or the region in general.

A proportion of Bulgarians and ethnic Macedonians have extremist views about their inter-relatedness. On the one hand, extremist ethnic Macedonians[83] seek to deny the possibility of any national, linguistic and historical relatedness to the Bulgarians. On the other hand, extremist Bulgarians seek to downplay this distinctiveness,[84] and are often supported by extremist Greeks.[85] Bulgarians and ethnic Macedonians seek to deny the self-identification of the Slavic speaking minority in northern Greece,[86] which mostly self-identifies as Greek. Extremists on all sides have been known to fabricate and reproduce falsified information, along with denying genuine information and propagating unscientific and pseudoscientific theories.[87][88][89]

Certain terms are in use by these groups as outlined below. Any denial of self-identification by any side, or any attribution of Macedonia related terms by third parties to the other side, can be seen as highly offensive. General usage of these terms follows:

|

|

|

Notes

n-[1] a b c During the Greek Civil War, in 1947, the Greek Ministry of Press and Information published a book, I Enandion tis Ellados Epivoulis ("Designs on Greece"), namely of documents and speeches on the ongoing Macedonian issue, many translations from Yugolsav officials. It reports Josip Broz Tito using the term "Aegean Macedonia" on the October 11, 1945 in the build up to the Greek Civil War; the original document is archived in ‘GFM A/24581/G2/1945’. For Athens, the "new term, Aegean Macedonia", (also "Pirin Macedonia"), was introduced by Yugoslavs. Contextually, this observation indicates this was part of the Yugoslav offensive against Greece, laying claim to Greek Macedonia, but Athens does not take issue with the term itself. The 1945 date concurs with Bulgarian sources. Further information on this can be found in the article Aegean Macedonia.

n-[2] a b Despite a history of use by Bulgarian nationalists,[111] the term "Pirin Macedonia" is today regarded as offensive by certain Bulgarians,[112] who assert that it is widely used by Macedonists as part of the irredentist concept of United Macedonia. However, many people in the country also think of the name as a purely geographical term, which it has historically been. Its use is, thus, controversial.

n-[3] a b c d e f g The constitutional name of the country "Republic of Macedonia" and the short name "Macedonia" when referring to the country, can be considered offensive by most Greeks, especially inhabitants of the Greek province of Macedonia. The official reasons for this, as described by the Greek Ministry of Foreign Affairs, are:

"The choice of the name Macedonia by FYROM directly raises the issue of usurpation of the cultural heritage of a neighbouring country. The name constitutes the basis for staking an exclusive rights claim over the entire geographical area of Macedonia. More specifically, to call only the Slavo-Macedonians Macedonians monopolizes the name for the Slavo-Macedonians and creates semiological confusion, whilst violating the human rights and the right to self-determination of Greek Macedonians. The use of the name by FYROM alone may also create problems in the trade area, and subsequently become a potential springboard for distorting reality, and a basis for activities far removed from the standards set by the European Union and more specifically the clause on good neighbourly relations. The best example of this is to be seen in the content of school textbooks in the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia."[80]

n-[4]^ The abbreviated term "FYROM" can be considered offensive when used to refer to the Republic of Macedonia. The spellout of the term, the "former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", is not necessarily considered offensive, but some ethnic Macedonians may still find it offensive due to their right of self-identification being ignored. The term can also be offensive for Greeks under certain contexts, since it contains the word Macedonia.

n-[5] a b c d Although acceptable in the past, current use of the name "Slavomacedonian" in reference to both the ethnic group and the language can be considered pejorative and offensive by ethnic Macedonians living in Greece. The Greek Helsinki Monitor reports:

"…the term Slavomacedonian was introduced and was accepted by the community itself, which at the time had a much more widespread non-Greek Macedonian ethnic consciousness. Unfortunately, according to members of the community, this term was later used by the Greek authorities in a pejorative, discriminatory way; hence the reluctance if not hostility of modern-day Macedonians of Greece (i.e. people with a Macedonian national identity) to accept it."[100]

Footnotes

- ↑ Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe - Southeast Europe (CEDIME-SE) - Macedonians of Bulgaria

- ↑ Odyssey VII 106

- ↑ LSJ, s.v.

- ↑ Hammond, N. G. L. (Dec., 1962). Classical Review, New Ser., Vol. 12, No. 3. pp. pp. 270–271.

- ↑ "Perseus encyclopedia" (in Ancient Greek & English translation). Herodotus, The Histories 1.56, 8.43. Retrieved on August, 3, 2006.

- ↑ Klein, Dr. Ernest (1967). A Comprehensive Etymological Dictionary of the English Language. Amsterdam, London, New York: Elsevier Publishing Company, Vol. II L - Z. p. p 919, Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 65-13229.

- ↑ "Online Etymology Dictionary". Macedonia. © November 2001 Douglas Harper. Retrieved on June, 20, 2007.

- ↑ "*māk-". The American Heritage Dictionary: Appendix I: Indo-European Roots (2004). Retrieved on 2007-12-22.

- ↑ Hoffman, J.B. (1950). Etymologischen Wörterbuch des Griechischen. München: Verlag von R. Oldenbourg. pp. under Μακρός.

- ↑ 10.0 10.1 McCarthy, J., 2001: The Ottoman Peoples and the End of Empire, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-340-70657-0, p.55.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 11.2 11.3 11.4 11.5 11.6 11.7 Wilkinson, H.R. (1951). Maps and Politics; a review of the ethnographic cartography of Macedonia. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press. pp. (a) p.1; (b) pp.2–4, 99, 121 ff.; (c) p.120; (d) pp.4, 99, 137; (e) pp. 2, 4. LCC DR701.M3 W5. http://worldcatlibraries.org/wcpa/oclc/244268?tab=holdings.

- ↑ Lane Fox, Robin (2004). Alessandro Magno. Turin: Einaudi. pp. pp. 17–21.

- ↑ Rostovtseff, History of the Ancient World, ii, 78.

- ↑ Warren Treadgold, A History of the Byzantine State and society (1997), pp. 421, 478, et passim.

- ↑ Imber, Colin (2002). The Ottoman Empire, 1300–1650: The structure of Power. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

- ↑ Inalcik, Halil; Translation by Norman Itzkowitz and Colin Imber (1973). The Ottoman Empire: The Classical Age 1300–1600. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

- ↑ Pitcher, Donald Edgar (1972). An Historical Geography of the Ottoman Empire. Leiden, Netherlands: E.J.Brill.

- ↑ Miller, William (1936). The Ottoman empire and its successors. Cambridge [Eng.]: The University Press. pp. 9, 447–9

- ↑ Comstock, John (1829). History of the Greek Revolution complied from official documents of the Greek Government... and other authentic sources. New York. p.5

- ↑ Poulton, Hugh (2000). "Greece". Who Are the Macedonians?. Indiana University Press. pp. 85–86. ISBN 0-253-21359-2. http://books.google.com/books?ie=UTF-8&hl=en&id=8_zeaeTOz6YC&pg=PA85&lpg=PA85&dq=85&prev=http://books.google.com/books%3Fq%3D%2522Who%2Bare%2Bthe%2BMacedonians%2522%2BPoulton&sig=NobKDU7Unvc2AqCZLCn0vSM5VIo.

- ↑ This article contains material from the Library of Congress Country Studies, which are United States government publications in the public domain. "The Library of Congress, Country Studies". Yugoslavia. Retrieved on July 17, 2006.

- ↑ 22.0 22.1 22.2 22.3 "International Constitutional Law" (in English translation). Macedonia — Constitution. Retrieved on July 20, 2006.

- ↑ 23.0 23.1 Oxford English Dictionary Unabridged — Draft Revision (Mar. 2005) — "Macedonian"

- ↑ 24.0 24.1 24.2 Danforth, L. M. (1997) The Macedonian Conflict: Ethnic Nationalism in a Transnational World, Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-04356-6, p.44

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 "myMacedonia.net". Retrieved on July 22, 2006.

- ↑ "Encyclopædia Britannica". Macedonia (2006). Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ "Official site: District of Blagoevgrad". Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ 28.0 28.1 28.2 "CIA — The World Factbook". Macedonia. Retrieved on July 18, 2006.

- ↑ "MSN Encarta". Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Retrieved on September 9, 2006.

- ↑ 30.0 30.1 30.2 "British Council — Bulgaria". Macedonians of Bulgaria. Retrieved on September 11, 2006.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 31.2 "State Statistical Office of the Republic of Macedonia" (pdf) (in English). 2002 census p.34. Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ (Greek) "General Secretariat of National Statistical Service of Greece" (zip xls). 2001 census. Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ Pomeroy, S., Burstein, S., Dolan, W., Roberts, J. (1998) Ancient Greece: A Political, Social, and Cultural History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-509742-4

- ↑ (Bulgarian) "National Statistical Institute (of Bulgaria)". 2001 census. Retrieved on August, 3, 2006.

- ↑ (Bulgarian) "Български новини". Поне един ден веселие и безгрижие. Retrieved on September 12, 2006.

- ↑ "Ethnologue". Report for Macedo-Romanian language. Retrieved on August, 3, 2006.

- ↑ 37.0 37.1 Oxford English Dictionary Unabridged — Draft Revision (Mar. 2005) — "Macedo-"

- ↑ Poulton, Hugh (1995, 2000). Who Are the Macedonians?. United Kingdom: C. Hurst & Co. Ltd.. pp. p. ix. ISBN 1-85065-534-0. http://books.google.com/books?id=ppbuavUZKEwC&vid=ISBN1850655340&dq=&pg=PR9&lpg=PR9&sig=pQh0ojlZmc7RraIH3hHiYmxCvX4&q.

- ↑ "Ethnologue". Report for Macedonian language. Retrieved on September 10, 2006.

- ↑ "The Linguist List". Retrieved on September 10, 2006.

- ↑ Masson, Olivier (2003) [1996]. S. Hornblower and A. Spawforth (eds.). ed.. The Oxford Classical Dictionary (revised 3rd ed. ed.). USA: Oxford University Press. pp. 905–906. ISBN 0-19-860641-9.

- ↑ Hammond, N.G.L. (1989), The Macedonian State. Origins, Institutions and History, Oxford University Press, ISBN 0-19-814927-1, pp 12–13

- ↑ (German) Ahrens, F. H. L. (1843), De Graecae linguae dialectis, Göttingen, 1839–1843 ; Hoffmann, O. Die Makedonen. Ihre Sprache und ihr Volkstum, Göttingen, 1906

- ↑ B. Joseph (2001): "Ancient Greek". In: J. Garry et al. (eds.) Facts about the world's major languages: an encyclopedia of the world's major languages, past and present. Online paper

- ↑ Mallory, J.P. and Adams, D.Q. (eds.) (1997), Encyclopedia of Indo-European culture, Taylor & Francis Inc., ISBN 1-884964-98-2, p.361

- ↑ (French) Dubois L. (1995) Une tablette de malédiction de Pella: s'agit-il du premier texte macédonien ?, Revue des Études Grecques (REG) 108:190–197

- ↑ (French) Brixhe C., Panayotou A. (1994) Le Macédonien in: Langues indo-européennes, ed. Bader, Paris, pp 205–220

- ↑ Lunt, H. (1986) "On Macedonian Nationality" in Slavic Review, Vol. 45, No. 4. pp. 729–734

- ↑ "United Nations". Admission of the State whose application is contained in document A/47/876-S/25147 to membership in the United Nations. Retrieved on July 17, 2006.

- ↑ "European Union". European Commission, Enlargement, The former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Retrieved on September, 5, 2006.

- ↑ "NATO". Enlargement. Retrieved on July 18, 2006.

- ↑ "International Monetary Fund". former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia and the IMF. Retrieved on July 18, 2006.

- ↑ "World Trade Organization". Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) and the WTO. Retrieved on July 20, 2006.

- ↑ "International Olympic Committee". Olympic Committee of the Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia. Retrieved on July 18, 2006.

- ↑ "World Bank". Countries & Regions. Retrieved on July 18, 2006.

- ↑ "EBRD European Bank for Reconstruction and Development". ebrd and fyr Macedonia. Retrieved on July 18, 2006.

- ↑ "The Organization for Security and Co-operation in Europe". Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia admitted to OSCE. Retrieved on July 18, 2006.

- ↑ "FIFA Organisation". FYR Macedonia. Retrieved on July 20, 2006.

- ↑ "FIBA Organisation". FYR Macedonia. Retrieved on July 20, 2006.

- ↑ Floudas, Demetrius Andreas; ""FYROM's Dispute with Greece Revisited"" (PDF). in: Kourvetaris et al (eds.), The New Balkans, East European Monographs: Columbia University Press, 2002, p. 85.

- ↑ 61.0 61.1 "Interim Accord between the Hellenic Republic and the former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia", United Nations, 13 September 1995.

- ↑ Gatzoulis, B.; Templar, M., A. (2000). "MACEDONIA? What's in a Name — A Rose by Any Other Name, Is It Still A Rose?". Pan-Macedonian Association USA, Inc. Retrieved on July 25, 2006.

- ↑ (Greek)"Official site of the Municipality of Thessaloniki". Speech by Thessaloniki Mayor Vassilis Papageorgopoulos in the protocol signing ceremony for sisterhood with Kolkata, India. Retrieved on July 25, 2006.

- ↑ Greek Macedonia "not a problem", The Times (London), August 5, 1957

- ↑ Patrides, Greek Magazine of Toronto, September — October, 1988, p. 3.

- ↑ Simons, Marlise (February 3 1992). "As Republic Flexes, Greeks Tense Up", New York Times.

- ↑ Lenkova, M.; Dimitras, P., Papanikolatos, N., Law, C. (eds) (1999). "Greek Helsinki Monitor: Macedonians of Bulgaria" (pdf). Minorities in Southeast Europe. Greek Helsinki Monitor, Center for Documentation and Information on Minorities in Europe — Southeast Europe. Retrieved on July 24, 2006.

- ↑ "Rainbow — Vinozhito political party". The Macedonian minority in Albania. Retrieved on July 22, 2006.

- ↑ "Makedonija — General Information". Retrieved on July 22, 2006.

- ↑ 70.0 70.1 Danforth, Loring M.. How can a woman give birth to one Greek and one Macedonian?. http://www.gate.net/~mango/How_can_a_woman_give_birth.htm. Retrieved on 2006-12-26. Most quotations within the text are from Evangelos Kofos: "Most precious jewels" from a Boston Globe article of January 5, 1993, the others from Nationalism and communism, Thessalonica, 1964

- ↑ "The vision of "Greater Macedonia"". Retrieved on September 14, 2006.

- ↑ "The vision of "Greater Macedonia"". Specific examples (I). Retrieved on September 14, 2006.

- ↑ "The vision of "Greater Macedonia"". Specific examples (II). Retrieved on September 14, 2006.

- ↑ The Macedonian Times, semi-governmental monthly periodical, Issue number 23, July-August 1996:14, Leading article: Bishop Tsarknjas

- ↑ Facts About the Republic of Macedonia - annual booklets since 1992, Skopje, Republic of Macedonia Secretariat of Information, Second edition, 1997, ISBN 9989-42-044-0. p.14. 2 August 1944.

- ↑ MIA (Macedonian Information Agency), Macedonia marks 30th anniversary of Dimitar Mitrev's death, Skopje, February 24 2006

- ↑ "Official site of the Embassy of the Republic of Macedonia in London". An outline of Macedonian history from Ancient times to 1991. Retrieved on 2006-12-26.

- ↑ Society for Macedonian Studies, Macedonianism FYROM'S Expansionist Designs against Greece, 1944-2006, Ephesus - Society for Macedonian Studies, 2007 ISBN 978-960-8326-30-9, Retrieved on 2007-12-05.

- ↑ Floudas, Demetrius Andreas; ""A Name for a Conflict or a Conflict for a Name? An Analysis of Greece's Dispute with FYROM",". 24 (1996) Journal of Political and Military Sociology, 285. Retrieved on 2007-01-24.

- ↑ 80.0 80.1 "Hellenic Republic, Ministry of Foreign Affairs" (in English). Former Yugoslav Republic of Macedonia (FYROM) — The Name Issue. Retrieved on July 17, 2006.

- ↑ (Greek) Skai News, ΠΑΣΟΚ: Βετό σε περίπτωση διπλής ονομασίας (Machine translation: PASOK: Veto in the case of dual designation), Retrieved on 2008-06-03.

- ↑ (Greek) Skai News, KΚΕ για Κόσοβο - ΠΓΔΜ (Machine translation: KKE for Kosovo - FYROM), Retrieved on 2008-06-03.

- ↑ "Macedonian Info". Retrieved on July 19, 2006.

- ↑ "Macedonian Scientific Institute". Retrieved on July 19, 2006.

- ↑ 85.0 85.1 (Greek) "Ελληνικές Γραμμές ("Hellenic Lines")". Retrieved on July 17, 2006.

- ↑ "Bulgarian Human Rights in Macedonia". Retrieved on July 19, 2006.

- ↑ Arnaiz-Villena, A.; Dimitroski K., Pacho A. et al (2001). "HLA genes in Macedonians and the sub-Saharan origin of the Greeks". (theory considered to "lack scientific merit", see below). Blackwell Publishing, Inc.. doi:10.1034/j.1399-0039.2001.057002118.x. Retrieved on July 23, 2006.

- ↑ Cavalli-Sforza, Luca, L.; Piazza A., Risch, N. (10 January 2002). "Comment on the above theory: Dropped genetics paper lacked scientific merit". Nature (Nature Publishing Group) 415 (415): 115. doi:. http://www.nature.com/cgi-taf/DynaPage.taf?file=/nature/journal/v415/n6868/full/415115b_r.html. Retrieved on 2006-07-23.

- ↑ McKie, Robin (November 25 2001). "Article regarding above theory". Journal axes gene research on Jews and Palestinians. The Observer International. Retrieved on July 23, 2006.

- ↑ (Bulgarian) Giza, Antony The Balkan Countries and the Macedonian Question , from: http://vmro[dot]150m.com/ag/ag_2_5.html (blocked by the spam blacklist)

- ↑ AIMpress Sofia — Skopje (22 February 2006). "Article: Bulgaria recognises Macedonian language". Press release. Retrieved on 2006-07-25.

- ↑ 92.0 92.1 (Bulgarian) Dimitrov, Bozhidar (2003). The Ten Lies of Macedonism. Strumica, Republic of Macedonia: Blaže Koneski. ISBN 954-07-1807-4. http://www.macedoniainfo.com/10_Lies_Macedonism2.htm.

- ↑ (Bulgarian) Todorov, Georgi. "Article: The construction of "Zograf" by Stefan the Great". Retrieved on July 25, 2006.

- ↑ 94.0 94.1 94.2 Tegopoulos, Fytrakis (1997). Μείζον Ελληνικό Λεξικό ("Mízon Hellinikó Lexikó"). Ekdoseis Armonia A.E.. pp. 674, 1389. ISBN 960-7598-04-0.

- ↑ "Greek Helsinki Monitor & Minority Rights Group-Greece (MRG-G)" (rtf). EBLUL and EUROLANG drop references to "Slavo-Macedonia Language" in favor of " Macedonian Language" following criticism by Macedonian diaspora and Minority rights NGOs (13 March 2002). Retrieved on July 25, 2006.

- ↑ Nystazopoulou — Pelekidou, M.; translated by: Kyzirakos I. (1992). "The republic of Skopje and the northest geographical boundaries of Macedonia" (in English). The "Macedonian Question": A Historical Review. Ionian University, ISBN 960-7260-01-5. Retrieved on July 23, 2006.

- ↑ His Beatitude the Archbishop of Athens and All Greece, Christodoulos (17 November 2004). "The Archbishop on the problem of the naming of the FYROM" (in English). Letters. Ecclesia: the official site of the Church of Greece. Retrieved on July 25, 2006.

- ↑ 98.0 98.1 (Greek) "Ελληνικές Γραμμες ("Hellenic Lines")". Retrieved on July 18, 2006.

- ↑ "Macedonian in different languages" (in English). Retrieved on July 19, 2006.

- ↑ 100.0 100.1 Greek Helsinki Monitor, MRG-G (1993–1996). "The Macedonians" (pdf). Retrieved on July 25, 2006.

- ↑ (Greek) "antibaro.gr". η επιστροφή των «Σλαβομακεδόνων» (the return of the «Slavomacedonians»). Retrieved on September 10, 2006.

- ↑ 102.0 102.1 (Macedonian) "Maкедонија (Macedonia)". ЕНЦИКЛОПЕДИЈА Британика (Encyclopedia Britannica). Скопје: Топер. 2005.

- ↑ (Macedonian) "A1 TV". Средба на Македонците од Егејска Македонија во Трново. Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ 104.0 104.1 (Macedonian) "Official webpage of the President of the Republic of Macedonia". Остварени средби на Претседателот Бранко Црвенковски за време на неговата посета на Канада. Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ (Bulgarian) Вѣнко Марковски. "Македонска Трибуна (Makedonska Tribuna)". Народ, който не познава своята собствена история, се поддава на асимилация. Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ 106.0 106.1 (Macedonian) "Vest Macedonia daily newspaper". Бугарофили и србофили се тепале за црквата Свети Никола. Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ (Macedonian) "Tribune". Кој го ослободи Марјановиќ од вистината? Кој за што, професорот за “најодвратните бугараши”. Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ (Macedonian) "A1 TV". Протест на „Виножито“ и на Македонците Егејци на Меџитлија. Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ "Biser Balkanski, Canadian Macedonian Internet Community". Definition of a Gerkoman. Retrieved on July 17, 2006.

- ↑ Malinovski, I. (May 23 2002). ""MARKOVGRAD"-Political Thought of the Serbian South.". Skoplje, FYROM. Retrieved on July 19, 2006.

- ↑ (Bulgarian) "VMRO-BND (Bulgarian National Party)". Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

- ↑ (Bulgarian) "Club for Fundamental Initiatives". КАК СТАВАХ НАЦИОНАЛИСТ. Retrieved on July 21, 2006.

Principal sources

- Borza, Eugene N. (1999). Before Alexander: constructing early Macedonia. Claremont, CA: Regina Books. ISBN 0-941690-97-0. (pb)

- Fox, Robin Lane (1973). Alexander the Great. Peinguin Books. ISBN 0-14-008878-4. (pb)

- Wilkinson, Henry Robert (1951). Maps and politics; a review of the ethnographic cartography of Macedonia. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press.