Lorentz transformation

In physics, the Lorentz transformation converts between two different observers' measurements of space and time, where one observer is in constant motion with respect to the other. In classical physics (Galilean relativity), the only conversion believed necessary was  , describing how the origin of one observer's coordinate system slides through space with respect to the other's, at speed v and along the x-axis of each frame. According to special relativity, this is only a good approximation at much smaller speeds than the speed of light, and in general the result is not just an offsetting of the x coordinates; lengths and times are distorted as well.

, describing how the origin of one observer's coordinate system slides through space with respect to the other's, at speed v and along the x-axis of each frame. According to special relativity, this is only a good approximation at much smaller speeds than the speed of light, and in general the result is not just an offsetting of the x coordinates; lengths and times are distorted as well.

If space is homogeneous, then the Lorentz transformation must be a linear transformation. Also, since relativity postulates that the speed of light is the same for all observers, it must preserve the spacetime interval between any two events in Minkowski space. The Lorentz transformations describe only the transformations in which the event at  ,

,  is left fixed, so they can be considered as a rotation of Minkowski space. The more general set of transformations that also includes translations is known as the Poincaré group.

is left fixed, so they can be considered as a rotation of Minkowski space. The more general set of transformations that also includes translations is known as the Poincaré group.

Henri Poincaré named the Lorentz transformations after the Dutch physicist and mathematician Hendrik Lorentz (1853–1928) in 1905.[1] They form the mathematical basis for Albert Einstein's theory of special relativity. They were derived by Joseph Larmor in 1897,[2] and Lorentz (1899, 1904).[3] In 1905 Einstein derived them under the assumptions of the principle of relativity and the constancy of the speed of light in any inertial reference frame.

Contents |

Lorentz transformation for frames in standard configuration

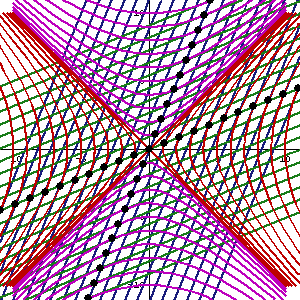

Assume there are two observers O and  , each using their own Cartesian coordinate system to measure space and time intervals. O uses

, each using their own Cartesian coordinate system to measure space and time intervals. O uses  and Q uses

and Q uses  . Assume further that the coordinate systems are oriented so that the x-axis and the x' -axis overlap, the y-axis is parallel to the y' -axis, as are the z-axis and the z' -axis. The relative velocity between the two observers is v along the common x-axis. Also assume that the origins of both coordinate systems are the same. If all these hold, then the coordinate systems are said to be in standard configuration. A symmetric presentation between the forward Lorentz Transformation and the inverse Lorentz Transformation can be achieved if coordinate systems are in symmetric configuration. The symmetric form highlights that all physical laws should be of such a kind that they remain unchanged under a Lorentz transformation.

. Assume further that the coordinate systems are oriented so that the x-axis and the x' -axis overlap, the y-axis is parallel to the y' -axis, as are the z-axis and the z' -axis. The relative velocity between the two observers is v along the common x-axis. Also assume that the origins of both coordinate systems are the same. If all these hold, then the coordinate systems are said to be in standard configuration. A symmetric presentation between the forward Lorentz Transformation and the inverse Lorentz Transformation can be achieved if coordinate systems are in symmetric configuration. The symmetric form highlights that all physical laws should be of such a kind that they remain unchanged under a Lorentz transformation.

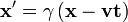

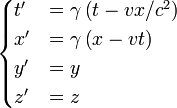

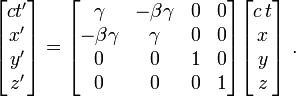

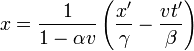

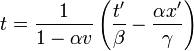

The Lorentz transformation for frames in standard configuration can be shown to be:

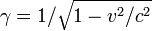

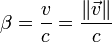

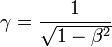

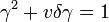

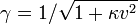

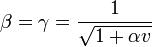

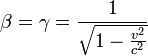

where  is called the Lorentz factor.

is called the Lorentz factor.

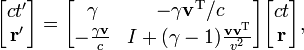

Matrix form

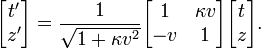

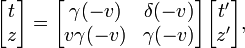

This Lorentz transformation is called a "boost" in the x-direction and is often expressed in matrix form as

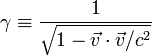

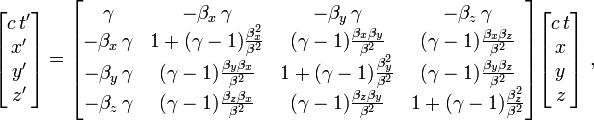

More generally for a boost in an arbitrary direction  ,

,

where  and

and  .

.

Note that this is only the "boost", i.e. a transformation between two frames in relative motion. But the most general proper Lorentz transformation also contains a rotation of the three axes. This boost alone is given by a symmetric matrix. But the general Lorentz transformation matrix is not symmetric.

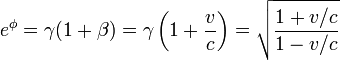

Rapidity

The Lorentz transformation can be cast into another useful form by introducing a parameter  called the rapidity (an instance of hyperbolic angle) through the equation:

called the rapidity (an instance of hyperbolic angle) through the equation:

Equivalently:

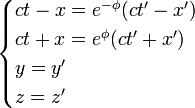

Then the Lorentz transformation in standard configuration is:

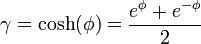

Hyperbolic trigonometric expressions

It can also be shown that:

and therefore,

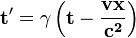

Hyperbolic rotation of coordinates

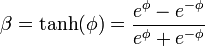

Substituting these expressions into the matrix form of the transformation, we have:

Thus, the Lorentz transformation can be seen as a hyperbolic rotation of coordinates in Minkowski space, where the rapidity  represents the hyperbolic angle of rotation.

represents the hyperbolic angle of rotation.

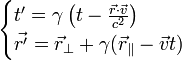

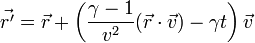

General boosts

For a boost in an arbitrary direction with velocity  , it is convenient to decompose the spatial vector

, it is convenient to decompose the spatial vector  into components perpendicular and parallel to the velocity

into components perpendicular and parallel to the velocity  :

:  . Then only the component

. Then only the component  in the direction of

in the direction of  is 'warped' by the gamma factor:

is 'warped' by the gamma factor:

where now  . The second of these can be written as:

. The second of these can be written as:

These equations can be expressed in matrix form as

where I is the identity matrix, v is velocity written as a column vector and vT is its transpose (a row vector).

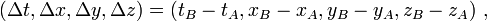

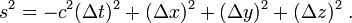

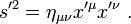

Spacetime interval

In a given coordinate system ( ), if two events

), if two events  and

and  are separated by

are separated by

the spacetime interval between them is given by

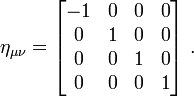

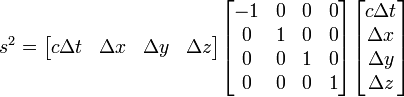

This can be written in another form using the Minkowski metric. In this coordinate system,

Then, we can write

or, using the Einstein summation convention,

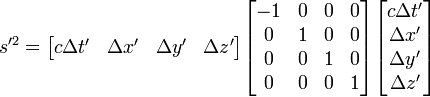

Now suppose that we make a coordinate transformation  . Then, the interval in this coordinate system is given by

. Then, the interval in this coordinate system is given by

or

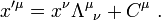

It is a result of special relativity that the interval is an invariant. That is,  . It can be shown[4] that this requires the coordinate transformation to be of the form

. It can be shown[4] that this requires the coordinate transformation to be of the form

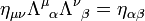

Here,  is a constant vector and

is a constant vector and  a constant matrix, where we require that

a constant matrix, where we require that

Such a transformation is called a Poincaré transformation or an inhomogeneous Lorentz transformation.[5] The  represents a space-time translation. When

represents a space-time translation. When  , the transformation is called an homogeneous Lorentz transformation, or simply a Lorentz transformation.

, the transformation is called an homogeneous Lorentz transformation, or simply a Lorentz transformation.

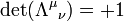

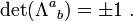

Taking the determinant of  gives us

gives us

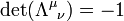

Lorentz transformations with  are called proper Lorentz transformations. They consist of spatial rotations and boosts and form a subgroup of the Lorentz group. Those with

are called proper Lorentz transformations. They consist of spatial rotations and boosts and form a subgroup of the Lorentz group. Those with  are called improper Lorentz transformations and consist of (discrete) space and time reflections combined with spatial rotations and boosts. They don't form a subgroup, as the product of any two improper Lorentz transformations will be a proper Lorentz transformation.

are called improper Lorentz transformations and consist of (discrete) space and time reflections combined with spatial rotations and boosts. They don't form a subgroup, as the product of any two improper Lorentz transformations will be a proper Lorentz transformation.

The composition of two Poincaré transformations is a Poincaré transformation and the set of all Poincaré transformations with the operation of composition forms a group called the Poincaré group. Under the Erlangen program, Minkowski space can be viewed as the geometry defined by the Poincaré group, which combines Lorentz transformations with translations. In a similar way, the set of all Lorentz transformations forms a group, called the Lorentz group.

A quantity invariant under Lorentz transformations is known as a Lorentz scalar.

Special relativity

One of the most astounding consequences of Einstein's clock-setting method is the idea that time is relative. In essence, each observer's frame of reference is associated with a unique set of clocks, the result being that time passes at different rates for different observers. This was a direct result of the Lorentz transformations and is called time dilation. We can also clearly see from the Lorentz "local time" transformation that the concept of the relativity of simultaneity and of the relativity of length contraction are also consequences of that clock-setting hypothesis.

Lorentz transformations can also be used to prove that magnetic and electric fields are simply different aspects of the same force — the electromagnetic force. If we have one charge or a collection of charges which are all stationary with respect to each other, we can observe the system in a frame in which there is no motion of the charges. In this frame, there is only an "electric field". If we switch to a moving frame, the Lorentz transformation will predict that a "magnetic field" is present. This field was initially unified in Maxwell's concept of the "electromagnetic field".

The correspondence principle

For relative speeds much less than the speed of light, the Lorentz transformations reduce to the Galilean transformation in accordance with the correspondence principle. The correspondence limit is usually stated mathematically as  , so it is usually said that non relativistic physics is a physics of "instant action at a distance"

, so it is usually said that non relativistic physics is a physics of "instant action at a distance"  .

.

History

- See also History of Lorentz transformations.

The transformations were first discovered and published by Joseph Larmor in 1897. In 1905, Henri Poincaré[6] named them after the Dutch physicist and mathematician Hendrik Antoon Lorentz (1853-1928) who had published a first order version of these transformations in 1895[7] and the final version in 1899 and 1904.

Many physicists, including FitzGerald, Larmor, Lorentz and Woldemar Voigt, had been discussing the physics behind these equations since 1887.[8][9] Larmor and Lorentz, who believed the luminiferous aether hypothesis, were seeking the transformations under which Maxwell's equations were invariant when transformed from the ether to a moving frame. In early 1889, Heaviside had shown from Maxwell's equations that the electric field surrounding a spherical distribution of charge should cease to have spherical symmetry once the charge is in motion relative to the ether. FitzGerald then conjectured that Heaviside’s distortion result might be applied to a theory of intermolecular forces. Some months later, FitzGerald published his conjecture in Science to explain the baffling outcome of the 1887 ether-wind experiment of Michelson and Morley. This became known as the FitzGerald-Lorentz explanation of the Michelson-Morley null result, known early on through the writings of Lodge, Lorentz, Larmor, and FitzGerald.[10] Their explanation was widely accepted as correct before 1905.[11] Larmor gets credit for discovering the basic equations in 1897 and for being first in understanding the crucial time dilation property inherent in his equations.[12]

Larmor's (1897) and Lorentz's (1899, 1904) final equations are algebraically equivalent to those published and interpreted as a theory of relativity by Albert Einstein (1905) but it was the French mathematician Henri Poincaré who first recognized that the Lorentz transformations have the properties of a mathematical group.[13] Both Larmor and Lorentz discovered that the transformation preserved Maxwell's equations. Paul Langevin (1911) said of the transformation:

- "It is the great merit of H. A. Lorentz to have seen that the fundamental equations of electromagnetism admit a group of transformations which enables them to have the same form when one passes from one frame of reference to another; this new transformation has the most profound implications for the transformations of space and time".[14]

Derivation

The usual treatment (e.g., Einstein's original work) is based on the invariance of the speed of light. However, this is not necessarily the starting point: indeed (as is exposed, for example, in the second volume of the Course in Theoretical Physics by Landau and Lifshitz), what is really at stake is the locality of interactions: one supposes that the influence that one particle, say, exerts on another can not be transmitted instantaneously. Hence, there exists a theoretical maximal speed of information transmission which must be invariant, and it turns out that this speed coincides with the speed of light in vacuum. The need for locality in physical theories was already noted by Newton (see Koestler's "The Sleepwalkers"), who considered the notion of an action at a distance "philosophically absurd" and believed that gravity must be transmitted by an agent (interstellar aether) which obeys certain physical laws.

Michelson and Morley in 1887 designed an experiment, which employed an interferometer and a half-silvered mirror, that was accurate enough to detect aether flow. The mirror system reflected the light back into the interferometer. If there were an aether drift, it would produce a phase shift and a change in the interference that would be detected. However, given the results were negative, rather than validating the aether, based upon the findings aether was not confirmed. This was a major step in science that eventually resulted in Einstein's Special Theory of Relativity.

In a 1964 paper,[15] Erik Christopher Zeeman showed that the causality preserving property, a condition that is weaker in a mathematical sense than the invariance of the speed of light, is enough to assure that the coordinate transformations are the Lorentz transformations.

From group postulates

Following is a classical derivation (see, e.g., [1] and references therein) based on group postulates and isotropy of the space.

Coordinate transformations as a group

The coordinate transformations between inertial frames form a group (called the proper Lorentz group) with the group operation being the composition of transformations (performing one transformation after another). Indeed the four group axioms are apparently satisfied:

- Closure: the composition of two transformations is a transformation: consider a composition of transformations from the inertial frame

to inertial frame

to inertial frame  , (denoted as

, (denoted as ![[K\to K']](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/1b7556e399257595538f6c8a6d968fe2.png) ), and then from

), and then from  to inertial frame

to inertial frame  ,

, ![[K'\to K'']](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/bb1385dbd227d7fb6a72810f3c7634bd.png) ; apparently there exists a transformation,

; apparently there exists a transformation, ![[K\to K'']](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/d616f305cf6d38da653bdce773bdd18d.png) , directly from an inertial frame

, directly from an inertial frame  to inertial frame

to inertial frame  .

. - Associativity: the result of

![\big([K\to K'][K'\to K'']\big)[K''\to K''']](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/1989d3a9aa77ebc8e761146fbac0a3fe.png) and

and ![[K\to K']\big([K'\to K''][K''\to K''']\big)](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/dff67f9e28d69032d72bac62984b167e.png) is apparently the same,

is apparently the same,  .

. - Identity element: there is an identity element, a transformation

.

. - Inverse element: for any transformation

there apparently exists an inverse transformation

there apparently exists an inverse transformation  .

.

Transformation matrices consistent with group axioms

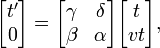

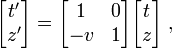

Let us consider two inertial frames, K and K', the latter moving with velocity  with respect to the former. By rotations and shifts we can choose the z and z' axes along the relative velocity vector and also that the events (t=0,z=0) and (t'=0,z'=0) coincide. Since the velocity boost is along the z (and z') axes nothing happens to the perpendicular coordinates and we can just omit them for brevity. Now since the transformation we are looking after connects two inertial frames, it has to transform a linear motion in (t,z) into a linear motion in (t',z') coordinates. Therefore it must be a linear transformation. The general form of a linear transformation is

with respect to the former. By rotations and shifts we can choose the z and z' axes along the relative velocity vector and also that the events (t=0,z=0) and (t'=0,z'=0) coincide. Since the velocity boost is along the z (and z') axes nothing happens to the perpendicular coordinates and we can just omit them for brevity. Now since the transformation we are looking after connects two inertial frames, it has to transform a linear motion in (t,z) into a linear motion in (t',z') coordinates. Therefore it must be a linear transformation. The general form of a linear transformation is

where  and

and  are some yet unknown functions of the relative velocity

are some yet unknown functions of the relative velocity  .

.

Let us now consider the motion of the origin of the frame K'. In the K' frame it has coordinates (t',z'=0), while in the K frame it has coordinates (t,z=vt). These two points are connected by our transformation

from which we get

.

.

Analogously, considering the motion of the origin of the frame K, we get

from which we get

.

.

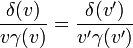

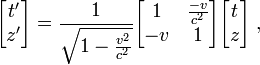

Combining these two gives  and the transformation matrix has simplified a bit,

and the transformation matrix has simplified a bit,

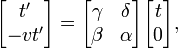

Now let us consider the group postulate inverse element. On one hand the inverse transformation is done simply by the inverse matrix,

On the other hand the inverse transformation is the one where  is substituted by

is substituted by  ,

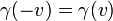

,

Now the function  can not depend upon the direction of

can not depend upon the direction of  because it is apparently the factor which defines the relativistic contraction and time dilation. These two (in an isotropic world of ours) cannot depend upon the direction of

because it is apparently the factor which defines the relativistic contraction and time dilation. These two (in an isotropic world of ours) cannot depend upon the direction of  . Thus,

. Thus,  and comparing the two matrices, we get

and comparing the two matrices, we get

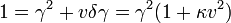

According to the closure group postulate a composition of two coordinate transformations is also a coordinate transformation, thus the product of two of our matrices should also be a matrix of the same form, in particular the diagonal elements should be equal. Calculating the product of two transformation matrices, one with  the other with

the other with  and comparing the diagonal elements and dividing through by the

and comparing the diagonal elements and dividing through by the  terms gives

terms gives

The denominator will be nonzero for nonzero v as  is always nonzero, as

is always nonzero, as  . If v=0 we have the identity matrix which coincides with putting v=0 in the matrix we get at the end of this derivation for the other values of v, making the final matrix valid for all nonnegative v.

. If v=0 we have the identity matrix which coincides with putting v=0 in the matrix we get at the end of this derivation for the other values of v, making the final matrix valid for all nonnegative v.

For the nonzero v, this combination of function must be a universal constant, one and the same for all inertial frames. Let's define this constant as  where

where  has the dimension of

has the dimension of  . Solving

. Solving

we finally get  and thus the transformation matrix, consistent with the group axioms, is given by

and thus the transformation matrix, consistent with the group axioms, is given by

If

If  were positive, then there would be transformations (with

were positive, then there would be transformations (with  ) which transform time into a spatial coordinate and vice versa. We exclude this on physical grounds, because time can only run in the positive direction. Thus two types of transformation matrices are consistent with group postulates: i) with the universal constant

) which transform time into a spatial coordinate and vice versa. We exclude this on physical grounds, because time can only run in the positive direction. Thus two types of transformation matrices are consistent with group postulates: i) with the universal constant  and ii) with

and ii) with  .

.

Galilean transformations

If  then we get the Galilean-Newtonian kinematics with the Galilean transformation,

then we get the Galilean-Newtonian kinematics with the Galilean transformation,

where time is absolute,  , and the relative velocity

, and the relative velocity  of two inertial frames is not limited.

of two inertial frames is not limited.

Lorentz transformations

If  is negative, then we set

is negative, then we set  which becomes the invariant speed, the speed of light in vacuum. This yields

which becomes the invariant speed, the speed of light in vacuum. This yields  and thus we get special relativity with Lorentz transformation

and thus we get special relativity with Lorentz transformation

where the speed of light is a finite universal constant determining the highest possible relative velocity between inertial frames.

If  the Galilean transformation is a good approximation to the Lorentz transformation.

the Galilean transformation is a good approximation to the Lorentz transformation.

Only experiment can answer the question which of the two possibilities,  or

or  , is realised in our world. The experiments measuring the speed of light, first performed by a Danish physicist Ole Rømer, show that it is finite, and the Michelson–Morley experiment showed that it is an absolute speed, and thus that

, is realised in our world. The experiments measuring the speed of light, first performed by a Danish physicist Ole Rømer, show that it is finite, and the Michelson–Morley experiment showed that it is an absolute speed, and thus that  .

.

From physical principles

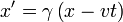

The problem is usually restricted to two dimensions by using a velocity along the x axis such that the y and z coordinates do not intervene. It is similar to that of Einstein.[16] More details may be found in[17] As in the Galilean transformation, the Lorentz transformation is linear : the relative velocity of the reference frames is constant. They are called inertial or Galilean reference frames. According to relativity no Galilean reference frame is privileged. Another condition is that the speed of light must be independent of the reference frame, in practice of the velocity of the light source.

Galilean reference frames

In classical kinematics, the total displacement x in the R frame is the sum of the relative displacement x' in frame R' and of the displacement x in frame R. If v is the relative velocity of R' relative to R, we have v : x = x’+vt or x’=x-vt. This relationship is linear for a constant v, that is when R and R' are Galilean frames of reference.

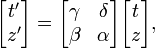

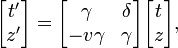

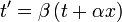

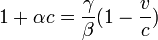

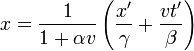

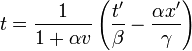

In Einstein's relativity, the main difference with Galilean relativity is that space is a function of time and vice-versa: t ≠ t’. The most general linear relationship is obtained with four constant coefficients, α, β, γ and v:

The Lorentz transformation becomes the Galilan transformation when β = γ = 1 and α = 0.

Speed of light independent of the velocity of the source

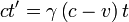

Light being independent of the reference frame as was shown by Michelson, we need to have x = ct if x’ = ct’. Replacing x and x' in the preceding equations, one has:

Replacing t’ with the help of the second equation, the first one writes:

After simplification by t and dividing by cβ, one obtains:

Principle of relativity

According to the principle of relativity, there is no privileged Galilean frame of reference. One has to find the same Lorentz transformation from frame R to R' or from R' to R. As in the Galilean transformation, the sign of the transport velocity v has to be changed when passing from one frame to the other.

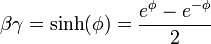

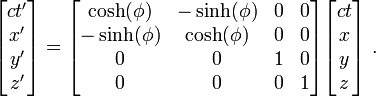

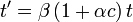

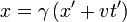

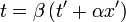

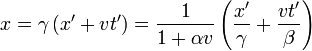

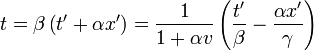

The following derivation uses only the principle of relativity which is independent of light velocity constancy. The inverse transformation of

is :

In accordance with the principle of relativity, the expressions of x and t are:

They have to be identical to those obtained by inverting the transformation except for the sign of the velocity of transport v:

We thus have the identities, verified for any x’ and t’ :

Finally we have the equalities :

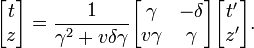

Expression of the Lorentz transformation

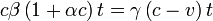

Using the relation

obtained earlier, one has :

and, finally:

We have now all the coefficients needed and, therefore, the Lorentz transformation :

The inverse Lorentz transformation writes, using the Lorentz factor γ:

See also

- Electromagnetic field

- Galilean transformation

- Hyperbolic rotation

- Invariance mechanics

- Lorentz group

- Principle of relativity

- Velocity-addition formula

- Algebra of physical space

References

- ↑ The reference is within the following paper: Poincaré, Henri (1905), "Sur la dynamique de l'électron", Comptes rendus hebdomadaires des séances de l'Académie des Sciences 140: 1504–1508

- ↑ Larmor, J. (1897), "A dynamical theory of the electric and luminiferous medium — Part III: Relations with material media", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 190: 205–300, doi:

- ↑ Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon (1899), "Simplified theory of electrical and optical phenomena in moving systems", Proc. Acad. Science Amsterdam I: 427–443; and Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon (1904), "Electromagnetic phenomena in a system moving with any velocity less than that of light", Proc. Acad. Science Amsterdam IV: 669–678

- ↑ Weinberg, Steven (1972), Gravitation and Cosmology, New York, [NY.]: Wiley, ISBN 0-471-92567-5: (Section 2:1)

- ↑ Weinberg, Steven (1995), The quantum theory of fields (3 vol.), Cambridge, [England] ; New York, [NY.]: Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-55001-7 : volume 1.

- ↑ Fric, Jacques (2003), Henri Poincaré: A Decisive Contribution to Special Relativity: the short story, http://www.everythingimportant.org/relativity/Poincare.htm

- ↑ See History of Special Relativity The work is contained within Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon (1895), Versuch einer theorie der electrischen und optischen erscheinungen in bewegten köpern, Leiden, [The Netherlands]: E.J. Brill, http://www.historyofscience.nl/search/detail.cfm?pubid=2690&view=image&startrow=1

- ↑ O'Connor, John J.; Robertson, Edmund F., A History of Special Relativity, http://www-groups.dcs.st-and.ac.uk/~history/HistTopics/Special_relativity.html

- ↑ Sinha, Supurna (2000), "Poincaré and the Special Theory of Relativity", Resonance 5: 12–15, doi:, http://www.iisc.ernet.in/academy/resonance/Feb2000/pdf/Feb2000p12-15.pdf

- ↑ Brown, Harvey R., Michelson, FitzGerald and Lorentz: the Origins of Relativity Revisited, http://philsci-archive.pitt.edu/archive/00000987/00/Michelson.pdf

- ↑ Rothman, Tony (2006), "Lost in Einstein's Shadow", American Scientist 94 (2): 112f., http://www.americanscientist.org/libraries/documents/200622102452_866.pdf

- ↑ Macrossan, Michael N. (1986), "A Note on Relativity Before Einstein", Brit. Journal Philos. Science 37: 232–34, http://espace.library.uq.edu.au/view.php?pid=UQ:9560

- ↑ Katzir, Shaul (2005), "Poincaré’s Relativistic Physics: Its Origins and Nature", Physics in Perspective 7: 268–292, doi:, http://www.everythingimportant.org/relativity/Poincare.pdf

- ↑ The citation is within the following paper: Langevin, P. (1911), "L'évolution de l'éspace et du temps", Scientia X: 31–54

- ↑ Zeeman, Erik Christopher (1964), "Causality implies the Lorentz group", Journal of Mathematical Physics 5 (4): 490–493, doi:

- ↑ Einstein, Albert (1916). "Relativity: The Special and General Theory" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-11-01.

- ↑ Bernard Schaeffer, Relativités et quanta clarifiés

Further reading

- Einstein, Albert (1961), Relativity: The Special and the General Theory, New York: Three Rivers Press (published 1995), ISBN 0-517-88441-0, http://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/einstein/works/1910s/relative/

- Ernst, A.; Hsu, J.-P. (2001), "First proposal of the universal speed of light by Voigt 1887", Chinese Journal of Physics 39 (3): 211–230, http://psroc.phys.ntu.edu.tw/cjp/v39/211.pdf

- Langevin, P. (1911), "L'évolution de l'éspace et du temps", Scientia X: 31–54

- Larmor, J. (1897), "Upon a dynamical theory of the electric and luminiferous medium", Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society 190: 205–300, doi:

- Larmor, J. (1900), Aether and matter, Cambridge, [England]: Cambridge University Press

- Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon (1899), "Simplified theory of electrical and optical phenomena in moving systems", Proc. Acad. Science Amsterdam I: 427–443

- Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon (1904), "Electromagnetic phenomena in a system moving with any velocity less than that of light", Proc. Acad. Science Amsterdam IV: 669–678

- Lorentz, Hendrik Antoon (1909), The theory of electrons and its applications to the phenomena of light and radiant heat; a course of lectures delivered in Columbia university, New York, in March and April 1906, Leipzig, [Germany] ; New York, [NY.]: B.G. Teubner ; G.E. Stechert

- Poincaré, Henri (1905), "Sur la dynamique de l'électron", Comptes Rendues 140: 1504–1508, http://www.soso.ch/wissen/hist/SRT/P-1905-1.pdf

- Thornton, Stephen T.; Marion, Jerry B. (2004), Classical dynamics of particles and systems (5th ed.), Belmont, [CA.]: Brooks/Cole, pp. 546–579, ISBN 0-534-40896-6

- Voigt, Woldemar (1887), "Über das Doppler'sche princip", Nachrichten von der Königlicher Gesellschaft den Wissenschaft zu Göttingen 2: 41–51

External links

- Derivation of the Lorentz transformations. This web page contains a more detailed derivation of the Lorentz transformation with special emphasis on group properties.

- The Paradox of Special Relativity. This webpage poses a problem, the solution of which is the Lorentz transformation, which is presented graphically in its next page.

- Relativity - a chapter from an online textbook

- Special Relativity: The Lorentz Transformation, The Velocity Addition Law on Project PHYSNET

- Warp Special Relativity Simulator. A computer program demonstrating the Lorentz transformations on everyday objects.

- Animation clip visualizing the Lorentz transformation.

![\phi = \ln \left[\gamma(1+\beta)\right] , -\phi = \ln \left[\gamma(1-\beta)\right] \,](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/50a7387ec59d9c33a4202883b6089785.png)

![\mathbf{ x=\frac{x' + vt'}{ \sqrt[]{1 -\frac{v^2}{c^2}} }}](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/ff13ec077ccdb7822145058decb6bb69.png)

![t=\mathbf{\frac{t' + \frac{vx'}{c^2}}{ \sqrt[]{1 -\frac{v^2}{c^2}}}}](/2009-wikipedia_en_wp1-0.7_2009-05/I/88c7b6dec9ed329d6b0d42df113822fa.png)