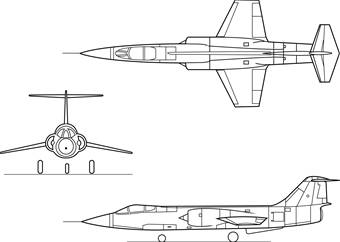

F-104 Starfighter

| F-104 Starfighter | |

|---|---|

|

|

| A Fokker-built, German-owned F-104G in USAF markings in August 1979 | |

| Role | Interceptor aircraft, fighter-bomber |

| Manufacturer | Lockheed |

| Designed by | Clarence "Kelly" Johnson |

| First flight | 4 March 1954 |

| Introduction | 20 February 1958 |

| Retired | 2004 (Italy) |

| Primary users | Luftwaffe United States Air Force Japan Air Self-Defense Force Turkish Air Force |

| Number built | 2,578 |

| Unit cost | US$1.42 million (F-104G)[1] |

| Developed from | Lockheed XF-104 |

| Variants | Lockheed NF-104A Canadair CF-104 Aeritalia F-104S CL-1200 Lancer and X-27 |

The Lockheed F-104 Starfighter was an American single-engined, high-performance, supersonic interceptor aircraft that served with the United States Air Force (USAF) from 1958 until 1967. One of the Century Series of aircraft, it continued in service with Air National Guard units until it was phased out in 1975. The National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) flew a small mixed fleet of F-104 types in supersonic flight tests and spaceflight programs until they were retired in 1994.[2] Several two-seat trainer versions were produced, the most numerous being the TF-104G.

USAF F-104Cs saw service during the Vietnam War, and F-104A aircraft were deployed by Pakistan briefly during the Indo-Pakistani wars. Republic of China Air Force F-104s also engaged the People's Liberation Army Air Force over the disputed island of Kinmen. A set of modifications produced the F-104G model, which won a NATO competition for a new fighter-bomber and saw widespread service with many European air forces into the late 1980s.

Lockheed developed the final and most advanced version for use by the Italian Air Force, the F-104S, which was designed to carry AIM-7 Sparrow missiles. The Italian Air Force was the last remaining Starfighter operator, retiring the last of its fleet in 2004. A projected, highly-modified version of the F-104, known as the CL-1200 Lancer, did not proceed; the project was cancelled at the mock-up stage.

The poor safety record of the Starfighter brought the aircraft into the public eye, especially in Luftwaffe service; the subsequent Lockheed bribery scandals surrounding the original purchase contracts caused considerable political controversy in Europe and Japan. However, a USAF study of other Century Series fighters revealed that the F-100 Super Sabre had a statistically higher accident rate than that of the F-104.[3]

Contents |

Development

Clarence "Kelly" Johnson, the chief engineer at Lockheed's Skunk Works, visited Korea in December 1951 and spoke with fighter pilots about what sort of aircraft they wanted. At the time, the U.S. pilots were confronting the MiG-15 with F-86 Sabres, and many of the American pilots felt that the MiGs were superior to the larger and more complex American design. The pilots requested a small and simple aircraft with excellent performance.[4]

On his return to the United States, Johnson immediately started the design of just such an aircraft. In March, his team was assembled; they studied several aircraft designs, ranging from small designs at 8,000 pounds (3.6 t), to fairly large ones at 50,000 pounds (23 t). The L-246 remained essentially identical to the L-083 Starfighter as eventually delivered.[4]

The design was presented to the Air Force in November 1952, and they were interested enough to create a new proposal and invite several companies to participate. Three additional designs were received: the Republic AP-55, an improved version of its prototype XF-91 Thunderceptor; the North American NA-212, which would eventually evolve into the F-107; and the Northrop N-102 Fang, a new General Electric J79-powered design. Although all were interesting, Lockheed had an insurmountable lead, and was granted a development contract in March 1953. The prototype was given the designation XF-104.[5]

Work progressed quickly, with a mock-up ready for inspection at the end of April, and work starting on two prototypes late in May. At the time, the J79 engine was not ready; both prototypes were instead designed to use the Wright J-65 engine, a licensed version of the Armstrong Siddeley Sapphire. The first prototype was completed by early 1954, and started flying in March. The total time from design to first flight was about two years; this was a very short time then and is an unheard of time today, when several years is typical.

In order to achieve the desired performance, Lockheed chose a minimalist approach: a design that would achieve high performance by wrapping the lightest, most aerodynamically efficient airframe possible around a single powerful engine. The emphasis was on minimizing drag and mass.

Design

Wings and tail surfaces

The F-104 featured a radical wing design. Most jet fighters of the period used a swept-wing or delta-wing planform. This allowed a reasonable balance between aerodynamic performance, lift, and internal space for fuel and equipment. Lockheed's tests, however, determined that the most efficient shape for high-speed, supersonic flight was a very small, straight, mid-mounted, trapezoidal wing. The new wing design was extremely thin, with a thickness-to-chord ratio of only 3.36% and an aspect ratio of 2.45. The wing's leading-edges were so thin (0.016 in / 0.41 mm) and sharp that they presented a hazard to ground crews, and protective guards had to be installed during ground operations. The thinness of the wings meant that fuel tanks and landing gear had to be contained in the fuselage. The hydraulic cylinders driving the ailerons had to be only one inch (25 mm) thick to fit. The wings had both leading- and trailing-edge flaps. The small, highly-loaded wing resulted in an unacceptably high landing speed, so a boundary layer control system (BLCS) of blown flaps was incorporated, bleeding engine air over the trailing-edge flaps to improve lift. The system was a boon to safe landings, although it proved to be a maintenance problem in service, and landing without the BLCS could be a harrowing experience.[6]

The stabilator (horizontal tail surface) was mounted atop the fin to reduce inertia coupling. Because the vertical tailfin was only slightly shorter than the length of each wing and nearly as aerodynamically effective, it could act as a wing on rudder application (a phenomenon known as Dutch roll). To offset this effect, the wings were canted downward, giving 10° anhedral.[6]

Fuselage

The Starfighter's fuselage had a high fineness ratio, i.e., tapering sharply towards the nose, and a small frontal area. The fuselage was tightly packed, containing the radar, cockpit, cannon, fuel, landing gear, and engine. This fuselage and wing combination provided extremely low drag except at high angle of attack (alpha), at which point induced drag became very high. As a result, the Starfighter had excellent acceleration, rate of climb and potential top speed, but its sustained turn performance was very poor. A later modification on the F-104A/B allowed use of the takeoff flap setting to M1.8/550 knots which materially improved maneverability. It was sensitive to control input, and extremely unforgiving to pilot error.

NACA wind tunnel tested a model of the F-104 to evaluate its stability, and found it became increasingly unstable at higher angles of attack, to the point that there was a recommendation to limit the servo-control power that generated those higher angles, and shake the stick to warn the pilot. In the same report, NACA stated that the wingtip tanks, possibly because of their stabilizing fins, somewhat reduced the model's instability problems at high angles of attack.

Engine

The F-104 was designed to use the General Electric J79 turbojet engine, fed by side-mounted intakes with fixed inlet cones optimized for supersonic speeds. Unlike some supersonic aircraft, the F-104 does not have variable-geometry inlets. Its thrust-to-drag ratio was excellent, allowing a maximum speed well in excess of Mach 2: the top speed of the Starfighter was limited more by the aluminium airframe structure and the temperature limits of the engine compressor than by thrust or drag (which gives an aerodynamic maximum speed of Mach 2.2). Later models used uprated marks of the J79, improving both thrust and fuel consumption significantly.

Ejection seat

Early Starfighters used a downward-firing ejection seat (the Stanley C-1), out of concern over the ability of an upward-firing seat to clear the tailplane. This presented obvious problems in low-altitude escapes, and some 21 USAF pilots failed to escape their stricken aircraft in low-level emergencies because of it. The downward-firing seat was soon replaced by the Lockheed C-2 upward-firing seat, which was capable of clearing the tail, although it still had a minimum speed limitation of 90 knots (170 km/h). Many export Starfighters were later retro-fitted with Martin-Baker zero-zero ejection seats, which had the ability to successfully eject the pilot from the aircraft even at zero altitude and zero airspeed.[7]

Avionics

The initial USAF Starfighters had a basic AN/ASG-14T ranging radar, TACAN, and a AN/ARC-34 UHF radio. The later international fighter-bomber aircraft had a much more advanced Autonetics NASARR radar, a simple infrared sight, a Litton LN-3 inertial navigation system, and an air data computer.

In the late 1960s, Lockheed developed a more advanced version of the Starfighter, the F-104S, for use by the Italian Air Force as an all-weather interceptor. The F-104S received a NASARR R21-G with a moving-target indicator and a continuous-wave illuminator for semi-active radar homing missiles, including the AIM-7 Sparrow and Selenia Aspide. The missile-guidance avionics forced the deletion of the Starfighter's internal cannon. In the mid-1980s surviving F-104S aircraft were updated to ASA standard (Aggiornamento Sistemi d'Arma, or Weapon Systems Update), with a much improved, more compact Fiat R21G/M1 radar.

Armament

The basic armament of the F-104 was the M61 Vulcan 20 mm Gatling gun. The Starfighter was the first aircraft to carry the new weapon, which had a rate of fire of 6,000 rounds per minute. The cannon, mounted in the lower part of the port fuselage, was fed by a 725-round drum behind the pilot's seat. It was omitted in all the two-seat models and some single-seat versions, including reconnaissance aircraft and the early Italian F-104S; the gun bay and ammunition tank were usually replaced by additional fuel tanks. Two AIM-9 Sidewinder air-to-air missiles could be carried on the wingtip stations, which could also be used for fuel tanks. The F-104C and later models added a centerline pylon and two underwing pylons for bombs, rocket pods, or fuel tanks. The centerline pylon could carry a nuclear weapon; a "catamaran" launcher for two additional Sidewinders could be fitted under the forward fuselage, although the installation had minimal ground clearance and made the seeker heads of the missiles vulnerable to ground debris. The F-104S models added a pair of fuselage pylons beneath the intakes available for conventional bomb carriage. The F-104S had an additional pylon under each wing, allowing for a maximum of nine.

Two-seat trainer

Several two-seat training versions of the Starfighter were produced. They were generally similar to the single-seater, but the additional cockpit required removing the cannon and some internal fuel (very early versions of the F-104B did have a cannon fitted but it became impractical for many reasons). The nose landing gear bay was repositioned and the strut retracted rearwards. Two-seaters were combat-capable with Sidewinder missiles, and, despite a slightly larger vertical fin and increased weight, had similar performance to the early model single-seat aircraft.

Operational history

USAF Air Defense Command

The F-104A initially served briefly with the USAF Air Defense Command / Aerospace Defense Command (ADC) as an interceptor, although neither its range nor armament were well-suited for that role. The first unit to become operational with the F-104A was the 83rd Fighter Interceptor Squadron on 20 February 1958, at Hamilton AFB, California. After just three months of service, the unit was grounded after a series of engine-related accidents. The aircraft were then fitted with the J79-3B engine and another three ADC units equipped with the F-104A. The USAF reduced their orders from 722 Starfighters to 155.[8] After only one year of service these aircraft were handed over to ADC-gained units of the Air National Guard, although it should be noted that the F-104 was intended as an interim solution while the ADC waited for delivery of the F-106 Delta Dart.[9]

USAF Tactical Air Command

The subsequent F-104C entered service with Tactical Air Command as a multi-role fighter and fighter-bomber. The 479th Tactical Fighter Squadron at George AFB, California was the first unit to equip with the type in September 1958. Although not an optimum platform for the theater, the F-104 did see limited service in the Vietnam War. Again, in 1967, these TAC aircraft were transferred to the Air National Guard.

Vietnam War

Commencing with the Operation Rolling Thunder campaign, the Starfighter was used both in the air-superiority role and in the air support mission; although it saw little aerial combat and scored no air-to-air kills, Starfighters were successful in deterring MiG interceptors.[10] Starfighter squadrons made two deployments to Vietnam, the first being from April 1965 to November 1965, flying 2,937 combat sorties. During that first deployment, two Starfighters were shot down by ground fire, one was shot down by a Chinese MiG-19 (Shenyang J-6) when the F-104 strayed over the border, and two F-104s were lost to a mid-air collision associated with that air-to-air battle.[11] The 476th Tactical Fighter Squadron deployed to Vietnam in April 1965 through July 1965, losing one Starfighter; and the 436th Tactical Fighter Squadron deployed to Vietnam in July 1965 through October 1965, losing four.[12]

Starfighters returned to Vietnam when the 435th Tactical Fighter Squadron deployed from June 1966 until July 1967, in which time they flew a further 2,269 combat sorties, for a total of 5,206 sorties. Nine more F-104s were lost; two F-104s to ground fire, three to surface-to-air missiles, and the final four losses were operational (engine failures). The Starfighters rotated and/or transitioned to F-4 Phantoms in July 1967, having lost a total of 14 F-104s to all causes in Vietnam.[13] F-104s operating in Vietnam were upgraded in service with APR-25/26 radar warning receiver equipment, and one example is on display in the Air Zoo in Kalamazoo, Michigan.[14]

The USAF was less than satisfied with the Starfighter and procured only 296 examples in single-seat and two-seat versions. At the time, USAF doctrine placed little importance on air superiority (the "pure" fighter mission), and the Starfighter was deemed inadequate for either the interceptor or tactical fighter-bomber role, lacking both payload capability and endurance compared to other USAF aircraft. Its U.S. service was quickly wound down after 1965, and the last USAF Starfighters left active service in 1969, but continued in use with the Puerto Rico ANG until 1975.[14]

The last use of the Starfighter in US markings was training German pilots for the Luftwaffe, with a wing of TF-104Gs and F-104Gs based at Luke Air Force Base, Arizona. Although operated in USAF markings, these aircraft (which included German built aircraft) were actually owned by Germany. They continued in use until 1983.[15]

1967 Taiwan Strait Conflict

On 13 January 1967, four Republic of China (Taiwan) Air Force F-104G aircraft engaged a formation of 12 MiG-19s of the People's Liberation Army Air Force over the disputed island of Kinmen. One MiG-19 was claimed shot down with one F-104 also lost.[16]

India-Pakistan Wars

At dawn on 6 September 1965, Flight Lieutenant Aftab Alam Khan in an F-104 claimed a Dassault Mystère IV destroyed over West Pakistan and another damaged, to mark the start of aerial combat in the Indo-Pakistani War of 1965. At that time it was claimed as the first combat kill by any Mach 2 aircraft, and the first missile kill for the Pakistan Air Force. Indian sources dispute this claim.[17] The PAF lost three F-104 Starfighters during the 1965 operations, scoring two kills in return, during the 1971 war, the Starfighter was no longer considered a dreaded fighter after MIG-21's success in every combat. However the F-104 Starfighter's only victim was an Alize aircraft which belonged to the Indian Navy, which was shot down when a Starfighter was returning home from an aborted mission.[18]

The Starfighter is also believed to have been instrumental in intercepting an Indian Air Force Folland Gnat earlier, on 3 September 1965. F-104s were vectored to intercept the Gnat flying over Pakistan, returning to its home base. The F-104s, closing in at supersonic speed, caused the Gnat pilot to lower the undercarriage and land at a nearby disused Pakistani airfield to surrender. The Indian AF claims Squadron Leader Brij Pal Singh (who later rose to be an Air Marshal) made a navigation error that led him to land on the Pakistani airstrip. Singh was taken as a POW and later released.[18] The IAF Gnat is now displayed at the PAF Museum, Karachi. In the 1971 war, four F-104As were lost in combat against the IAF MiG-21s. One pilot successfully ejected from his F-104 over shark infested waters, but was never found by the Indian rescue team.[19]

International service

At the same time that the F-104 was falling out of U.S. favor, the Federal German Airforce was looking for a multi-role combat aircraft. The Starfighter was presented and reworked to convert it from a fair-weather fighter into an all-weather ground-attack, reconnaissance and interceptor aircraft, as the F-104G. The aircraft found a new market with other NATO countries, and eventually a total of 2,578 of all variants of the F-104 were built in the U.S. and abroad for various nations. Several countries received their aircraft under the U.S.-funded Military Aid Program (MAP). The American engine was retained but built under license in Europe, Canada and Japan. The Lockheed ejector seats were retained initially but were replaced later in some countries by the statistically safer Martin-Baker zero-zero ejection seat.

The so-called "Deal of the Century" produced substantial income for Lockheed. However, the resulting Lockheed bribery scandals caused considerable political controversy in Europe and Japan. In Germany, the Minister of Defence Franz Josef Strauss was accused of having received at least US$10 million for West Germany's purchase of the F-104 Starfighter in 1961.[20] Prince Bernhard of the Netherlands later confessed to having received more than US$1 million in bribes. In the 1970s it was revealed that Lockheed had engaged in an extensive campaign of bribery of foreign officials to obtain sales, a scandal that nearly led to the downfall of the ailing corporation.

The international service of the F-104 began to wind down in the late 1970s, being replaced in many cases by the F-16 Fighting Falcon, but it remained in service with some air forces for another two decades. The last operational Starfighters served with the Italian AMI, which retired them the 31 October 2004.

Flying the F-104

The Starfighter was generally considered a rewarding, if very demanding, "sports car" of a fighter. It was the first combat aircraft capable of sustained Mach 2 flight, and its speed and climb performance remain impressive even by modern standards. If used appropriately, with high-speed surprise attacks and good use of its exceptional thrust-to-weight ratio, it could be a formidable opponent, although being lured into a turning contest with a slower, more maneuverable opponent (as Pakistani pilots were with Indian Hunters in 1965) was perilous. The F-104's large turn radius was mainly due to the high speeds involved, and its high-alpha stalling and pitch-up behavior was known to command respect.

Takeoff speeds were in the region of 190 knots, with the pilot needing to swiftly raise the landing gear to avoid exceeding the limit speed of 260 knots (480 km/h). Climb and cruise performance were outstanding; unusually, a "slow" light illuminated on the instrument panel at around Mach 2 to indicate that the engine compressor was nearing its limiting temperature and the pilot needed to throttle-back. Returning to the circuit, the downwind leg could be flown at 210 knots (390 km/h) with "land" flap selected, while long flat final approaches were typically flown at speeds around 180 knots (330 km/h) depending on the weight of fuel remaining. High engine power had to be maintained on the final approach to ensure adequate airflow for the BLC system; consequently pilots were warned not to cut the throttle until the aircraft was actually on the ground. A drag chute and effective brakes shortened the Starfighter's landing roll.[21]

Safety record

The safety record of the F-104 Starfighter became high profile news especially in Germany in the mid 1960s, and lingers in the minds of the public even to this day. Some operators lost nearly one third of their aircraft through accidents, although the accident rate varied widely depending on the user and operating conditions; the Spanish Air Force, for example, lost none. The Starfighter was a particular favorite of the Aeronautica Militare Italiana (Italian Air Force), although the AMI's accident rate was far from the lowest of Starfighter users.

Notable U.S. Air Force pilots who lost their lives in F-104 accidents include Major Robert H. Lawrence, Jr. and Captain Iven Kincheloe. Civilian (retired USAAF) pilot Joe Walker died in a midair collision with an XB-70 Valkyrie while flying an F-104. Chuck Yeager was nearly killed when he lost control of an NF-104A during a high-altitude record-breaking attempt. He lost the tips of two fingers and was hospitalized for a long period with severe burns after the flight.

F-104 General characteristics

The F-104 series all had a very high wing loading (made even higher when carrying external stores), which demanded that sufficient airspeed be maintained at all times. The high angle of attack area of flight was protected by a stick shaker system to warn the pilot of an approaching stall, and if this was ignored a stick kicker system would pitch the aircraft's nose down to a safer angle of attack; this was often overridden by the pilot despite flight manual warnings against this practice. At extreme high angles of attack the F-104 was known to "pitch-up" and enter a spin, which in most cases was impossible to recover from. Unlike the twin-engined F-4 Phantom II for example, the F-104 with its single engine lacked the safety margin in the case of an engine failure, and had a very poor glide ratio without thrust.

Early problems

The J79 was a new engine that continued to be developed during the YF-104A test phase and in service with the F-104A. The engine featured variable incidence compressor stator blades, a design feature that altered the angle of the stator blades automatically with altitude and temperature. A condition known as "T-2 reset", a normal function that made large stator blade angle changes, caused several engine failures on takeoff. It was discovered that large and sudden temperature changes (from being parked in the sun to getting airborne) were falsely causing the engine stator blades to close and choke the compressor. The dangers presented by these engine failures were compounded by the downward ejection seat which gave the pilot little chance of a safe exit at low level. The engine systems were subsequently modified and the ejection seat changed to the more conventional upward type. Uncontrolled tip-tank oscillations sheared one wing off of an F-104B; this problem was apparent during testing of the XF-104 prototype and was eventually resolved by filling the tank compartments in a specific order.[22]

Later problems

A further engine problem was that of "uncommanded" opening of the variable thrust nozzle (usually through loss of engine oil); although the engine would be running normally at high power, the opening of the nozzle resulted in a drastic loss of thrust. A modification program installed a manual nozzle closure control which reduced the problem. The engine was also known to suffer from afterburner blow out on takeoff or even non-ignition resulting in a major loss of thrust, which could be detected by the pilot – the recommended action was to abandon the takeoff. The first fatal accident in German service was caused by this. Some aircrews experienced uncommanded "stick kicker" activation at low level when flying straight and level, so F-104 crews often flew with the system de-activated. Asymmetric flap deployment was another common cause of accidents, as was a persistent problem with severe nosewheel "shimmy" on landing which usually resulted in the aircraft leaving the runway and in some cases even flipping over onto its back.[23]

German service

The introduction of a highly technical aircraft type to a newly reformed air force was fraught with problems. Many pilots and ground crew had settled into civilian jobs after World War II and had not kept pace with developments, with pilots being sent on short "refresher" courses in slow and benign-handling first generation jet aircraft. Ground crew were similarly employed with minimal training and experience. Operating in poor North West European weather conditions (vastly unlike the fair weather training conditions at Luke AFB in Arizona) and flying at high speed and low level over hilly terrain, a great many accidents were attributed to CFIT or Controlled Flight Into Terrain (or water), which it is fair to say was no fault of the aircraft. Luftwaffe losses totaled 110 pilots lost.[24]

Many Canadian losses were attributed to the same cause as both air forces were operating in the same country. An additional factor was that the aircraft were parked outside in adverse weather conditions (snow, rain etc) where the moisture affected the delicate avionic systems. It was further noted that the Lockheed C-2 ejection seat was no guarantee of a safe escape and the Luftwaffe retro-fitted the much more capable Martin Baker GQ-7A seat from 1967, and many operators quietly followed suit. In 1966 Johannes Steinhoff took over command of the Luftwaffe and grounded the entire F-104 fleet until he was satisfied that problems had been resolved or at least reduced. In later years the German safety record improved, although a new problem of structural failure of the wings emerged. Original fatigue calculations had not taken into account the high number of g-force loading cycles that the German F-104 fleet was experiencing, and many airframes were returned for depot maintenance where their wings were replaced, while other aircraft were simply retired. Towards the end of Luftwaffe service, some aircraft were modified to carry an ADR or 'Black Box' which could give an indication of what might have caused the accident.[25] It may be noted that the German fighter ace Erich Hartmann had deemed the F-104 to be an unsafe aircraft with poor handling characteristics for aerial combat and had judged the fighter unfit for Luftwaffe use, even before its introduction, to the dismay of his superiors.[26]

Normal operating hazards

The causes of a large number of aircraft losses were the same as for any other similar type. They included: birdstrikes (particularly to the engine), lightning strikes, pilot spatial disorientation, and mid-air collisions with other aircraft. A particularly notable accident occurred on 19 June 1962 when a formation of four F-104F aircraft, practicing for the type's introduction-into-service ceremony, crashed together after descending through a cloud bank. This accident was explained as probable spatial disorientation of the lead pilot, and formation aerobatic teams were consequently banned by the Luftwaffe from that day on.[27]

Safety comparison with other aircraft types

A USAF comparison study of the accident rate of all the Century Series, F-4 Phantom, A-7, and F-111 aircraft over 750,000 flying hours showed that the F-100 Super Sabre led the table with an accident rate over double that of the F-104 (471 accidents for the F-100 versus 196 for the F-104) which had the second-highest rate, closely followed by the F-102 Delta Dagger.[3] It should be noted that the F-104 figures in this study were taken over 600,000 hours since that type had not reached 750,000 hours at the time.

Variants

A total of 2,578 F-104s were produced by Lockheed and under license by various foreign manufacturers. Principal variants included:

- XF-104

- Two prototype aircraft equipped with Wright J65 engines (the J79 was not yet ready); one aircraft equipped with the M61 cannon as an armament test bed. Both aircraft were destroyed in crashes.

- YF-104A

- 17 pre-production aircraft used for engine, equipment, and flight testing. Most were later converted to F-104A standard.

- F-104A

- A total of 153 initial production versions were built. In USAF service from 1958 through 1960, then transferred to ANG until 1963 when they were recalled by the USAF Air Defense Command for the 319th and 331st Fighter Interceptor Squadrons. Some were released for export to Jordan, Pakistan, and Taiwan, each of whom used it in combat. In 1967 the 319th F-104As and Bs were re-engined with the J79-GE-19 engines with 17,900 lb (79.6 kN) of thrust in afterburner; service ceiling with this engine was in excess of 73,000 ft (22,250 m). In 1969 all the F-104A/Bs in ADC service were retired. On 18 May 1958, an F-104A set a world speed record of 1,404.19 mph (2,259.82 km/h).

- NF-104A

- Three demilitarized versions with an additional 6,000 lbf (27 kN) Rocketdyne LR121/AR-2-NA-1 rocket engine, used for astronaut training at altitudes up to 120,800 ft (36,830 m). An accident on 10 December 1963 involving Chuck Yeager was depicted in the motion picture The Right Stuff, although the aircraft in the film was not an actual NF-104A.

- QF-104A

- A total of 22 F-104As converted into radio-controlled drones and test aircraft.

- F-104B

- Tandem two-seat dual-control trainer version of F-104A, 26-built. Enlarged rudder and ventral fin, no cannon and reduced internal fuel, but otherwise combat-capable. A few were supplied to Jordan, Pakistan and Taiwan.

- F-104C

- Fighter bomber versions for USAF Tactical Air Command, with improved fire-control radar (AN/ASG-14T-2), centerline and two wing pylons (for a total of five), and ability to carry one Mk 28 or Mk 43 nuclear weapon on the centerline pylon. The F-104C also had in-flight refuelling capability. On 14 December 1959, an F-104C set a world altitude record of 103,395 ft (31.5 km), 77 built.

- F-104D

- Dual-control trainer versions of F-104C, 21 built.

- F-104DJ

- Dual-control trainer version of F-104J for Japanese Air Self-Defense Force, 20 built by Lockheed and assembled by Mitsubishi.

- F-104F

- Dual-control trainers based on F-104D, but using the upgraded engine of the F-104G. No radar, and not combat-capable. Produced as interim trainers for the Luftwaffe. All F-104F aircraft were retired by 1971, 30-built.

- F-104G

- 1,122 aircraft of the main version produced as multi-role fighter bombers. Manufactured by Lockheed, and under license by Canadair and a consortium of European companies which included MBB, Messerschmitt, Fiat, Fokker and SABCA. The type featured strengthened fuselage and wing structure, increased internal fuel capacity, an enlarged vertical fin, strengthened landing gear with larger tires and revised flaps for improved combat maneuvering. Upgraded avionics included a new Autonetics NASARR F15A-41B radar with air-to-air and ground mapping modes, the Litton LN-3 inertial navigation system (the first on a production fighter) and an infrared sight.

- RF-104G

- 189 tactical reconnaissance models based on F-104G, usually with three KS-67A cameras mounted in the forward fuselage in place of cannon.

- TF-104G

- 220 combat-capable trainer version of F-104G; no cannon or centerline pylon, reduced internal fuel. One aircraft used by Lockheed as a demonstrator with the civil registration number L104L, was flown by Jackie Cochran to set three women’s world speed records in 1964. This aircraft later served in the Netherlands.

- F-104H

- Projected export version based on a F-104G with simplified equipment and optical gunsight. Not built.

- F-104J

- Specialized interceptor version of the F-104G for the Japanese ASDF, built under license by Mitsubishi for the air-superiority fighter role, armed with cannon and four Sidewinders; no strike capability. Some were converted to UF-104J radio-controlled target drones and destroyed. Total of 210 built, three built by Lockheed, 29 built by Mitsubushi for Lockheed built components and 177 built by Mitsubishi.

- F-104N

- Three F-104Gs were delivered to NASA in 1963 for use as high-speed chase aircraft. One, piloted by Joe Walker, collided with an XB-70 on 8 June 1966.

- F-104S

- 246 Italian versions produced by FIAT, one aircraft crashed prior to delivery and is often not included in the total number built. The F-104S was upgraded for the interception role having NASARR R-21G/H radar with moving-target indicator and continuous-wave illuminator for SARH missiles (initially AIM-7 Sparrow), two additional wing and two underbelly hardpoints (increasing the total to nine), more powerful J79-GE-19 engine with 11,870 lbf (53 kN) and 17,900 lbf (80 kN) thrust, and two additional ventral fins for increased stability. The M61 cannon was sacrificed to make room for the missile avionics in the interceptor version but retained for the fighter-bomber variants. Up to two Sparrow; and two, theoretically four or six Sidewinder missiles were carried on all the hardpoints except the central (underbelly), or seven 340 kg bombs (normally two–four 227–340 kg). The F-104S was cleared for a higher maximum takeoff weight, allowing it to carry up to 7,500 lb (3,400 kg) of stores; other Starfighters had a maximum external load of 4,000 lb (1,814 kg). Range was up to 1,250 km with four tanks.[28]

- F-104S-ASA

- (Aggiornamento Sistemi d'Arma – "Weapon Systems Update") – 147 upgraded F-104S with Fiat R21G/M1 radar with frequency hopping, look-down/shoot-down capability, new IFF system and weapon delivery computer, provision for AIM-9L all-aspect Sidewinder and Selenia Aspide missiles.

- F-104S-ASA/M

- (Aggiornamento Sistemi d'Arma/Modificato – "Weapon Systems Update/Modified") – 49 airframes upgraded in 1998 to ASA/M standard with GPS, new TACAN and Litton LN-30A2 INS, refurbished airframe, improved cockpit displays. All strike-related equipment was removed. The last Starfighters in combat service, they were withdrawn in December 2004 and temporarily replaced by the F-16 Fighting Falcon, while awaiting Eurofighter Typhoon deliveries.

- CF-104

- 200 Canadian-built versions, built under license by Canadair and optimized for nuclear strike, having NASARR R-24A radar with air-to-air modes, cannon deleted (restored after 1972), additional internal fuel cell, and Canadian J79-OEL-7 engines with 10,000 lbf (44 kN) /15,800 lbf (70 kN) thrust.

- CF-104D

- 38 dual-control trainer versions of CF-104, built by Lockheed, but with Canadian J79-OEL-7 engines. Some later transferred to Denmark, Norway and Turkey.

Production summary table and costs

Production summary table

| Type | Lockheed | Multi-national | Canadair | Fiat | Fokker | MBB | Messerschmitt | Mitsubishi | SABCA | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XF-104 | 2 | 2 | ||||||||

| YF-104A | 17 | 17 | ||||||||

| F-104A | 153 | 153 | ||||||||

| F-104B | 26 | 26 | ||||||||

| F-104C | 77 | 77 | ||||||||

| F-104D | 21 | 21 | ||||||||

| F-104DJ | 20 | 20 | ||||||||

| CF-104 | 200 | 200 | ||||||||

| CF-104D | 38 | 38 | ||||||||

| F-104F | 30 | 30 | ||||||||

| F-104G | 139 | 140 | 164 | 231 | 50 | 210 | 188[a] | 1122 | ||

| RF-104G | 40 | 35 | 119 | 194 | ||||||

| TF-104G (583C to F) | 172 | 27 | 199 | |||||||

| TF-104G (583G and H) | 21 | 21 | ||||||||

| F-104J | 3 | 207 | 210 | |||||||

| F-104N | 3 | 3 | ||||||||

| F-104S | 245[a] | 245 | ||||||||

| Total by manufacturer | 741 | 48 | 340 | 444 | 350 | 50 | 210 | 207 | 188 | 2578 |

Note: [a] One aircraft crashed on test flight and is not included.

Source: Table data taken from Bowman, Lockheed F-104 Starfighter.[29]

Costs

| F-104A | F-104B | F-104C | F-104D | F-104G | TF-104G | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Unit R&D cost | 189,473 | 189,473 | ||||

| Airframe | 1,026,859 | 1,756,388 | 863,235 | 873,952 | ||

| Engine | 624,727 | 336,015 | 473,729 | 271,148 | 169,000 | |

| Electronics | 3,419 | 13,258 | 5,219 | 16,210 | ||

| Armament | 19,706 | 231,996 | 91,535 | 269,014 | ||

| Ordnance | 29,517 | 59,473 | 44,684 | 70,067 | ||

| Flyaway cost | 1.7 million | 2.4 million | 1.5 million | 1.5 million | 1.42 million | 1.26 million |

| Modification costs by 1973 | 198,348 | 196,396 | ||||

| Cost per flying hour | 655 | |||||

| Maintenance cost per flying hour | 395 | 544 | 395 | 395 |

Note: Costs are in approximately 1960 United States dollars and have not been adjusted for inflation.[1]

Operators

A civilian demonstration team in Florida operates three Starfighters,[30] and another is owned and operated by a private collector[31] in Arizona.

The F-104 was operated by the militaries of the following nations.

Belgium

Belgium Canada

Canada Republic of China

Republic of China Denmark

Denmark Germany

Germany Greece

Greece Italy

Italy Japan

Japan Jordan

Jordan Netherlands

Netherlands Norway

Norway Pakistan

Pakistan Spain

Spain Turkey

Turkey United States

United States

Survivors

- F-104C Starfighter, 56-0914, is on display at the USAF Museum in Dayton, Ohio.[32]

- F-104G Starfighter, R-756, is displayed outside at the Midland Air Museum, Coventry, England.[33][34]

- F-104G Starfighter, 22+35 is on display at Lasham airfield, England, 2006.[35]

- F-104G Starfighter, 20+47 is on external display at the Internationales Luftfahrtmuseum, Manfred Pflumm, in Villingen-Schwenningen, Germany.[36]

- F-104G is on static display at the Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey.[37]

- F-104G Starfighter, 26+23, is preserved at the Air Museum of Spain, in Madrid, Spain. The aircraft is an ex-Luftwaffe machine which retains its German markings on the left side but is unusually painted with Spanish markings on the right side.[38]

- F-104G is on static display at The Air Victory Museum, South Jersey Regional Airport, Lumberton, NJ (Painted as RNLAF "D-8090" but is actually ex-Belgian Air Force FX-81).[39]

- F-104G, Royal Netherlands Air Force D-8331, is on static display in the Science Museum Oklahoma in Oklahoma City, OK.[40]

- F-104J Starfighter, 36-8515 is preserved at Kakamigahara Aerospace Museum, Kakamigahara, Japan.[41]

- F-104N, N811NA, flown by Neil Armstrong, is on static display at the Embry-Riddle Aeronautical University Prescott, Arizona campus.[42]

- F-104N, N812NA, is on display at Lockheed Palmdale, Calif. "Skunk Works" facility.[43]

Specifications (F-104G)

Data from Quest for Performance[44]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 54 ft 8 in (16.66 m)

- Wingspan: 21 ft 9 in (6.36 m)

- Height: 13 ft 6 in (4.09 m)

- Wing area: 196.1 sq ft (18.22 m²)

- Airfoil: Biconvex 3.36% root and tip

- Empty weight: 14,000 lb (6,350 kg)

- Loaded weight: 20,640 lb (9,365 kg)

- Max takeoff weight: 29,027 lb (13,170 kg)

- Powerplant: 1× General Electric J79-GE-11A afterburning turbojet

- Dry thrust: 10,000 lbf (48 kN)

- Thrust with afterburner: 15,600 lbf (69 kN)

- Zero-lift drag coefficient: 0.0172

- Drag area: 3.37 sq ft (0.31 m²)

- Aspect ratio: 2.45

Performance

- Maximum speed: 1,328 mph (1,154 knots, 2,125 km/h)

- Combat radius: 420 mi (365 NM, 670 km)

- Ferry range: 1,630 mi (1,420 nm, 2,623 km)

- Service ceiling 50,000 ft (15,000 m)

- Rate of climb: 48,000 ft/min (244 m/s)

- Wing loading: 105 lb/sq ft (514 kg/m²)

- Thrust/weight: 0.54 with max. takeoff weight (0.76 loaded)

- Lift-to-drag ratio: 9.2

Armament

- Guns: 1× 20 mm (0.787 in) M61 Vulcan gatling gun, 725 rounds

- Hardpoints: 7 with a capacity of 4,000 lb (1,800 kg),with provisions to carry combinations of:

- Missiles: 4× AIM-9 Sidewinder* Other: Bombs, rockets, or other stores

Popular culture

The Starfighter was featured in music and film. The German controversy over the Starfighter's contract and its toll on pilots inspired a rock concept album by Robert Calvert of Hawkwind, called Captain Lockheed and the Starfighters. It repeated the commonplace grim joke in Germany that the cheapest way of obtaining a Starfighter was to buy a small patch of land and simply wait.[45] After Kai-Uwe von Hassel succeeded Strauss as minister of defence, his son Oberleutnant Joachim von Hassel died in a Starfighter crash. This event was the topic of the Welle:Erdball song, "Starfighter F-104G".

Stock footage of F-104s was used when a U.S. Air Force F-104 intercepted the USS Enterprise in the Star Trek first season episode, "Tomorrow is Yesterday". In the remastered version of the episode, the stock footage was replaced by Computer-Generated Imagery. An F-104G Starfighter in the guise of an NF-104A was featured in the 1983 film The Right Stuff. The 1964 movie The Starfighters, about the training and operations of F-104 crews was subsequently featured in episode #612 of Mystery Science Theater 3000. The film starred future US Congressman Robert Dornan.

Nicknames

The Starfighter was commonly called the "missile with a man in it"; a name swiftly trademarked by Lockheed for marketing purposes. The term "Super Starfighter" was used by Lockheed to describe the F-104G in marketing campaigns, but fell into disuse. In service, American pilots called it the "Zipper" or "Zip-104" because of its prodigious speed. The Japan Air Self-Defense Force called it Eiko ("Glory"). A less charitable name appeared, "The Flying Coffin" from the translation of the common German public name of Fliegender Sarg. The F-104 was also called Witwenmacher ("Widowmaker"), or Erdnagel ("ground nail") – the official military term for a tent peg.[46] The Pakistani AF name was Badmash ("Hooligan"), while among Italian pilots its spiky design earned it the nickname Spillone ("Hatpin"), along with Bara volante ("Flying coffin"). Canadian pilots sometimes referred to it as the "flying lawn dart" or "Widowmaker".[47]

The engine made a unique howling sound at certain throttle settings which led to NASA F-104B Starfighter N819NA being named Howling Howland.[46]

See also

- Century Series

- Zero length launch

- North American Eagle

Related development

- Lockheed XF-104

- Lockheed NF-104A

- Canadair CF-104

- Aeritalia F-104S

- CL-1200 Lancer and X-27

Comparable aircraft

- F-11 Tiger

- Dassault Mirage III

- Northrop F-5

- EWR VJ 101

- English Electric Lightning

Related lists

- List of F-104 Starfighter operators

- List of fighter aircraft

- List of military aircraft of the United States

References

Notes

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Knaack 1978.

- ↑ F-104 Starfighter, NASA, 1 February 2005.

- ↑ 3.0 3.1 Bowman 2000, p. 21.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 Bowman 2000, p. 26.

- ↑ Bowman 2000, p. 32.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Bowman 2000, p. 28.

- ↑ Ejection seats of the F-104 Retrieved: 6 February 2008

- ↑ Ferdinand C.W. Käsmann 1994 p.84

- ↑ Bowman 2000, p. 39.

- ↑ Thompson 2004, p. 155.

- ↑ Smith and Herz 1992.

- ↑ Thompson 2004, p. 157.

- ↑ Two Cs from the 435th Retrieved: 6 February 2008.

- ↑ 14.0 14.1 Hobson 2001

- ↑ Fricker and Jackson 1996, p.74.

- ↑ Bowman 2000, p. 165.

- ↑ Jagan and Chopra, 2006.

- ↑ 18.0 18.1 Claims and Counter Claims, Pakdef.info. Retrieved: 6 February 2008.

- ↑ Indian Air Force : Down the Memory Lane, Indian MoD. Retrieved: 29 July 2008

- ↑ "The Lockheed Mystery", Time magazine, September 13, 1976. Retrieved: 6 February 2008.

- ↑ Bowman 2000, pp. 40, 43.

- ↑ Drendel 1976, p. 22.

- ↑ Bowman 2000

- ↑ New Scientist, "Too gung-ho", Vol 199 No. 2666, 26 July 2008, p17

- ↑ Reed 1981, p. 46.

- ↑ Toliver & Constable 1985, p. 285–286 (German)

- ↑ Kropf 2002, Ch. 10.

- ↑ Sgarlato 2004

- ↑ Bowman 2000, Appendix II.

- ↑ Starfighters F-104 Demo Team web site Retrieved: 6 February 2008

- ↑ See 5303 (104633), civil registry: N104JR on Lockheed CF-104D Starfighter, J Baugher, January 20, 2003.

- ↑ http://www.nationalmuseum.af.mil/factsheets/factsheet.asp?id=377 Retrieved: 18 May 2008.

- ↑ On loan from the USAF Museum.

- ↑ Midland Air Museum Retrieved: 6 February 2008.

- ↑ Luftfahrt Museum: Second World War Aircraft Preservation Society Retrieved: 6 February 2008.

- ↑ Flugplatz-Scwenningen.de (German language) Retrieved: 22 October 2008.

- ↑ F-104 Starfighter photos on METU campus, metu.edu.tr.

- ↑ 916.de Retrieved: 22 October 2008

- ↑ Wreckhunters.be Retrieved: 22 October 2008

- ↑ International F-104 Society Retrieved: 22 October 2008

- ↑ Kakamigahara Aerospace Museum Retrieved: 12 April 2008

- ↑ Where Are They Now? The NASA Dryden Flight Research Center's Historic Aircraft, NASA/Dryden Flight Research Center, October 8, 2008.

- ↑ Airliners.net Retrieved: 22 October 2008

- ↑ Loftin, LK, Jr. Quest for Performance: The Evolution of Modern Aircraft. NASA SP-468 Quest for Performance Retrieved: 22 April 2006.

- ↑ Bashow 1990, p. 93. Quote: "...just buy an acre of land anywhere in Germany, Sooner or later..."

- ↑ 46.0 46.1 Bashow 1986, p. 16.

- ↑ Cold Lake Airforce Museum, Cold Lake Airforce Museum.

Bibliography

- Bashow, David L. Starfighter: A Loving Retrospective of the CF-104 Era in Canadian Fighter Aviation, 1961-1986. Stoney Creek, Ontario: Fortress Publications Inc., 1990. ISBN 0-91919-512-1.

- Bashow, David L. "Starwarrior: A First Hand Look at Lockheed's F-104, One of the Most Ambitious Fighters ever Designed!" Wings Vol. 16, no. 3, June 1986.

- Bowman, Martin W. Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. Ramsbury, Marlborough, Wiltshire, UK: Crowood Press Ltd., 2000. ISBN 1-86126-314-7.

- Donald, David, ed. Century Jets. Norwalk, Connecticut: AIRtime Publishing, 2003. ISBN 1-880588-68-4.

- Drendel, Lou. F-104 Starfighter in action, Aircraft No. 27. Carrollton, Texas: Squadron/Signal Publications, 1976. ISBN 0-89747-026-5.

- Fricker, John and Jackson, Paul. "Lockheed F-104 Starfighter". Wings of Fame. Volume 2 1996., p. 38-99. Aerospace Publishing. London. ISBN 1-874023-69-7.

- Green, William and Swanborough, Gordon. The Great Book of Fighters. St. Paul, Minnesota: MBI Publishing, 2001. ISBN 0-7603-1194-3.

- Higham, Robin and Williams, Carol. Flying Combat Aircraft of USAAF-USAF (Vol.2). Manhattan, Kansas: Sunflower University Press, 1978. ISBN 0-8138-0375-6.

- Hobson, Chris. Vietnam Air Losses, USAF, USN, USMC, Fixed-Wing Aircraft Losses in Southeast Asia 1961–1973. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2001. ISBN 1-85780-1156.

- Jackson, Paul A. German Military Aviation 1956-1976. Hinckley, Leicestershire, UK: Midland Counties Publications, 1976. ISBN 0-904597-03-2.

- Jagan, Mohan P.V.S. and Chopra, Samir. The India-Pakistan Air War of 1965. New Delhi: Manohar, 2006. ISBN 8-17304-641-7.

- Käsmann, Ferdinand C.W. Die schnellsten Jets der Welt (German language) Planegg 1994 ISBN 3-925505-26-1.

- Kinzey, Bert. F-104 Starfighter in Detail & Scale. Blue Ridge Summit, Pennsylvania: TAB books, 1991. ISBN 1-85310-626-7.

- Knaack, Marcelle Size. Encyclopedia of USAF Aircraft and Missile Systems: Vol 1 Post-WW II Fighters 1945-1973. Washington, DC: Office of Air Force History, 1978. ISBN 0-912799-59-5

- Kropf, Klaus. German Starfighters. Hinckley, Leicestershire, UK: Midland Counties Publications, 2002. ISBN 1-85780-124-5.

- Nicolli, Ricardo. "Starfighters in the AMI". Air International Volume 31, No. 6, December 1986, p. 306-313, 321-322.

- Pace, Steve. Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. Oscela, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International, 1992. ISBN 0-87938-608-8.

- Pace, Steve. X-Fighters: USAF Experimental and Prototype Fighters, XP-59 to YF-23. St. Paul, Minnesota: Motorbooks International, 1991. ISBN 0-87938-540-5.

- Reed, Arthur. F-104 Starfighter – Modern Combat Aircraft 9. London: Ian Allan Ltd., 1981. ISBN 0-7110-1089-7.

- Sgarlato, Nico. "F-104 Starfighter" (in Italian). Delta editions, Great Planes Monograph series, February 2004.

- Smith, Philip E. and Herz, Peggy. Journey Into Darkness. 1992. ISBN 067-172-8237.

- Stachiw, Anthony L. and Tattersall, Andrew. CF104 Starfighter (Aircraft in Canadian Service). St. Catharine's, Ontario: Vanwell Publishing Limited, 2007. ISBN 1-55125-114-0.

- Thompson, Warren. "Starfighter in Vietnam". International Air Power Review. Volume 12, Spring 2004. Norwalk, Connecticut, USA: AirTime Publishing. 2004. ISBN 1-880588-77-3.

- Toliver, Raymond F. & Constable, Trevor J. (1985). Holt Hartmann vom Himmel!. Stuttgart, Germany: Motorbuch Verlag. ISBN 3-87943-216-3

- Upton, Jim. Warbird Tech - Lockheed F-104 Starfighter. North Branch, Minnesota: Specialty Press, 2003. ISBN 1-58007-069-8.

External links

- Lockheed XF-104 to F-104A, F-104B/D, F-104C, and F-104G pages on USAF National Museum site

- Baugher's F-104 Index Page variants and operators

- Photos from F-104N Joe Walker crash site

- Site of Chuck Yeager NF-104A crash

- List of F-104s on display and list of Canadair CF-104 Starfighters on display in Canada from Aero-Web.org

- F-104F Starfighter at the Deutsches Museum, Munich

|

||||||||

|

||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||