Lithuanian language

| Lithuanian Lietuvių kalba |

||

|---|---|---|

| Spoken in: | Lithuania, Argentina, Australia, Belarus, Brazil, Canada, Estonia, Kazakhstan, Latvia, Poland, Russia, Sweden, United Kingdom, Ireland, Uruguay, USA [1] | |

| Region: | Europe | |

| Total speakers: | 2.96 million (Lithuania) 170,000 (Abroad) 3.13 million (Worldwide)[1] |

|

| Ranking: | 144th | |

| Language family: | Indo-European Balto-Slavic Baltic Eastern Lithuanian |

|

| Writing system: | Roman script | |

| Official status | ||

| Official language in: | ||

| Regulated by: | Commission of the Lithuanian Language | |

| Language codes | ||

| ISO 639-1: | lt | |

| ISO 639-2: | lit | |

| ISO 639-3: | lit | |

| Note: This page may contain IPA phonetic symbols in Unicode. | ||

Lithuanian (lietuvių kalba), is the official state language of Lithuania and is recognised as one of the official languages of the European Union. There are about 2.96 million native Lithuanian speakers in Lithuania and about 170,000 abroad. Lithuanian is a Baltic language, closely related to Latvian, although they are not mutually intelligible. It is written in the Roman script.

Contents |

History

Anyone wishing to hear how Indo-Europeans spoke should come and listen to a Lithuanian peasant.

—Antoine Meillet

Lithuanian still retains many of the original features of the nominal morphology found in the common ancestors of the Indo-European languages, and has therefore been the focus of much study in the area of Indo-European linguistics. Studies in the field of comparative linguistics have shown it to be the most conservative living Indo-European language.[2][3]

Lithuanian and other Baltic languages passed through Proto-Balto-Slavic stage, during which Baltic languages developed numerous exclusive and non-exclusive lexical, morphological, phonological and accentual isoglosses with Slavic languages, which represent their closest living Indo-European relative. Moreover, with Lithuanian being so archaic in phonology, Slavic words can often be deduced from Lithuanian by regular sound laws.

According to some glottochronological speculations the Eastern Baltic languages split from the Western Baltic ones between 400 AD and 600 AD. The differentiation between Lithuanian and Latvian started after 800 AD; for a long period they could be considered dialects of a single language. At a minimum, transitional dialects existed until the 14th or 15th century, and perhaps as late as the 17th century. Also, the 13th- and 14th-century occupation of the western part of the Daugava basin (closely coinciding with the territory of modern Latvia) by the German Sword Brethren had a significant influence on the languages' independent development.

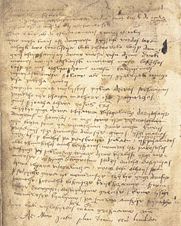

The earliest surviving written Lithuanian text is a translation dating from about 1503–1525 of the Lord's Prayer, the Hail Mary and the Nicene Creed written in the Southern Aukštaitijan dialect. Printed books existed after 1547, but the level of literacy among Lithuanians was low through the 18th century and books were not commonly available. In 1864, following the January Uprising, Mikhail Muravyov, the Russian Governor General of Lithuania, banned the language in education and publishing, and barred use of the Latin alphabet altogether, although books printed in Lithuanian continued to be printed across the border in East Prussia and in the United States. Brought into the country by book smugglers despite the threat of stiff prison sentences, they helped fuel a growing nationalist sentiment that finally led to the lifting of the ban in 1904.

Jonas Jablonskis (1860-1930) made significant contributions to the formation of the standard Lithuanian language. The conventions of written Lithuanian had been evolving during the 19th century, but Jablonskis, in the introduction to his Lietuviškos kalbos gramatika, was the first to formulate and expound the essential principles that were so indispensable to its later development. His proposal for Standard Lithuanian was based on his native Western Aukštaitijan dialect with some features of the eastern Prussian Lithuanians' dialect spoken in Lithuania Minor. These dialects had preserved archaic phonetics mostly intact due to the influence of the neighbouring Old Prussian language, while the other dialects had experienced different phonetic shifts. Lithuanian has been the official language of Lithuania since 1918. During the Soviet occupation (see History of Lithuania), it was used in official discourse along with Russian which, as the official language of the USSR, took precedence over Lithuanian.

Classification

Lithuanian is one of two living Baltic languages, along with Latvian. An earlier Old Prussian Baltic language was extinct by the 19th century; the other Western Baltic languages, Curonian and Sudovian, went extinct earlier. The Baltic languages form their own distinct branch of the Indo-European languages.

Geographic distribution

Lithuanian is spoken mainly in Lithuania. It is also spoken by ethnic Lithuanians living in today's Belarus, Latvia, Poland, and the Kaliningrad Oblast of Russia, as well by sizable emigrant communities in Argentina, Australia, Brazil, Canada, Denmark, Estonia, France, Iceland, Ireland, Norway, Russia proper, Sweden, the United Kingdom, the United States, and Uruguay.

2,955,200 people in Lithuania (including 3,460 Tatars), or about 80% of the 1998 population, are native Lithuanian speakers; most Lithuanian inhabitants of other nationalities also speak Lithuanian to some extent. The total worldwide Lithuanian-speaking population is about 4,000,000 (1993 UBS).

Official status

Lithuanian is the state language of Lithuania and an official language of the European Union.

Dialects

The Lithuanian language has two dialects (tarmės): Aukštaičių (Aukštaitian, Highland Lithuanian), Žemaičių/Žemaitiu (Samogitian, Lowland Lithuanian), See maps at [1]. There are significant differences between standard Lithuanian and Samogitian. The modern Samogitian dialect formed in the 13th-16th centuries under the influence of the Curonian language. Lithuanian dialects are closely connected with ethnographical regions of Lithuania

Dialects are divided into subdialects (patarmės). Both dialects have 3 subdialects. Samogitian is divided into West, North and South; Aukštaitian into West (Suvalkiečiai), South (Dzūkai) and East. Each subdialect is divided into smaller units - speeches (šnektos).

The standard Lithuanian is derived mostly from Western Aukštaitian dialects, including the Eastern dialect of Lithuania Minor. Influence of other dialects is more significant in vocabulary of the standard Lithuanian.

Sounds

Vowels

Lithuanian has 12 written vowels. In addition to the standard Roman letters, the ogonek ('little tail') accent (conventionally known as the caudata) is used to indicate long vowels, and is a historical relic of a time when these vowels were nasalized (as ogonek vowels are in modern Polish), and at an even earlier time had made diphthongs with an 'n' sound.

| Majuscule | A | Ą | E | Ę | Ė | I | Į | Y | O | U | Ų | Ū |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minuscule | a | ą | e | ę | ė | i | į | y | o | u | ų | ū |

| IPA | ɐ ɐː |

ɐː | æ æː |

æː | eː | i | iː | iː | oː o |

u | uː | uː |

Consonants

Lithuanian uses 20 consonant characters, drawn from the Roman alphabet. In addition, the digraph "Ch" represents a voiceless velar fricative (IPA [x]); the pronunciation of other digraphs can be deduced from their component elements.

| Majuscule | B | C | Č | D | F | G | H | J | K | L | M | N | P | R | S | Š | T | V | Z | Ž |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Minuscule | b | c | č | d | f | g | h | j | k | l | m | n | p | r | s | š | t | v | z | ž |

| IPA | b | ʦ | ʧ | d | f | ɡ | ɣ | j | k | l | m | n | p | r | s | ʃ | t | ʋ | z | ʒ |

Phonology

Consonants

| labial | dental | alveo- dental |

alveolar | alveo- palatal |

velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| plosives | voiceless | p | t | k | |||

| voiced | b | d | ɡ | ||||

| fricatives | voiceless | f | s | ʃ | x | ||

| voiced | z | ʒ | ɣ | ||||

| affricates | voiceless | ʦ | ʧ | ||||

| voiced | ʣ | ʤ | |||||

| nasal | m | n | |||||

| liquid | lateral | l | |||||

| glide | ʋ | j | |||||

| rhotic trill | r | ||||||

Each consonant (except [j]) has two forms: palatalized and non-palatalized ([bʲ] - [b],[dʲ] - [d], [ɡʲ] - [ɡ] and so on). The consonants [f x ɣ] and their palatalized versions are only found in loanwords. The consonants preceding vowels [i] and [e] are always moderately palatalized, a feature common to East Slavic languages and not present in the Latvian language.

Unreleased stops are common in the Lithuanian language over released plosives.

(Adapted from http://www.lituanus.org/1982_1/82_1_02.htm with necessary changes according to Lithuanian Language Encyclopedia[4])

Vowels

There are two possible ways to organize the Lithuanian vowel system. The traditional pattern has six long vowels and five short ones, with length as its distinctive feature:

| Front | Central | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long | Short | Long | Short | ||

| High | iː | i | uː | u | |

| Mid | eː | oː | o | ||

| Mid-low | ɛː | ɛ | |||

| Low | ɐː | ɑ | |||

(Adapted from http://www.lituanus.org/1982_1/82_1_02.htm and http://www.lituanus.org/1972/72_1_05.htm .)

However, at least one researcher suggests that a tense vs. lax distinction may be the actual distinguishing feature, or may be at least equally important as vowel length.[5] Such a hypothesis yields the chart below, where 'long' and 'short' have been preserved to parallel the terminology used above.

| Front | Back | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Long | Short | Long | Short | |

| High | iː | ɪ | uː | ʊ |

| Mid | eː | ε | oː | ɔ |

| Low | æː | a | ɐː | ʌ |

Grammar

The Lithuanian language is a highly inflected language in which the relationships between parts of speech and their roles in a sentence are expressed by numerous flexions.

There are two grammatical genders in Lithuanian - feminine and masculine. There is no neuter gender per se, but there are some forms which are derived from the historical neuter gender, notably attributive adjectives. There are five noun and three adjective declensions.

Nouns and other parts of nominal morphology are declined in seven cases: nominative, genitive, dative, accusative, instrumental, locative, and vocative. In older Lithuanian texts three additional varieties of the locative case are found: illative, adessive and allative. The most common are the illative, which still is used, mostly in spoken language, and the allative, which survives in the standard language in some idiomatic usages. The adessive is nearly extinct. These additional cases are probably due to the influence of Finno-Ugric languages with which Baltic languages have had a long-standing contact (Finno-Ugric languages have a great variety of noun cases a number of which are specialised locative cases).

Lithuanian has a free, mobile stress, and is also characterized by pitch accent.

The Lithuanian verbal morphology shows a number of innovations. Namely, the loss of synthetic passive (which is hypothesized based on the more archaic though long-extinct Indo-European languages), synthetic perfect (formed via the means of reduplication) and aorist; forming subjunctive and imperative with the use of suffixes plus flexions as opposed to solely flections in , e. g., Ancient Greek; loss of the optative mood; merging and disappearing of the -t- and -nt- markers for third person singular and plural, respectively (this, however, occurs in Latvian and Old Prussian as well and may indicate a collective feature of all Baltic languages).

On the other hand, the Lithuanian verbal morphology retains a number of archaic features absent from most modern Indo-European languages (but shared with Latvian). This includes the synthetic formation of the future tense with the help of the -s- suffix; three principal verbal forms with the present tense stem employing the -n- and -st- infixes.

There are three verbal conjugations. All verbs have present, past, past iterative and future tenses of the indicative mood, subjunctive (or conditional) and imperative moods (both without distinction of tenses) and infinitive. These forms, except the infinitive, are conjugative, having two singular, two plural persons and the third person form common both for plural and singular. Lithuanian has the richest participle system of all Indo-European languages, having participles derived from all tenses with distinct active and passive forms, and several gerund forms.

In practical terms, the rich overall inflectional system renders word order less important than in more isolating languages such as English. A Lithuanian speaker may word the English phrase "a car is coming" as either "atvažiuoja automobilis" or "automobilis atvažiuoja".

Lithuanian also has a very rich word derivation system and an array of diminutive suffixes.

The first prescriptive grammar book of Lithuanian was commissioned by the Duke of Prussia, Frederick William, for use in the Lithuanian-speaking parishes of East-Prussia. It was written in Latin and German by Daniel Klein and published in Königsberg in 1653/1654. The first scientific Compendium of Lithuanian language was published in German in 1856/57 by August Schleicher, a professor at Prague University. In it he describes Prussian-Lithuanian which later is to become the "skeleton" (Buga) of modern Lithuanian.

Today there are two definitive books on Lithuanian grammar: one in English, the "Introduction to Modern Lithuanian" (called "Beginner's Lithuanian" in its newer editions) by Leonardas Dambriūnas, Antanas Klimas and William R. Schmalstieg, and another in Russian, Vytautas Ambrazas' "Грамматика литовского языка" ("The Grammar of the Lithuanian Language"). Another recent book on Lithuanian grammar is the second edition of "Review of Modern Lithuanian Grammar" by Edmund Remys, published by Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, Chicago, 2003.

Vocabulary

Indo-European vocabulary

Lithuanian is considered one of the most conservative modern Indo-European languages. This conservativism becomes especially apparent when Lithuanian is compared to a Germanic or a Romance language as languages of these groups have greatly simplified their inflectional systems or levelled declension all together. Slavic languages are, on the other hand, more similar to Lithuanian.

Lithuanian retains cognates to many words found in classical languages, such as Sanskrit and Latin. These words are descended from Proto-Indo-European. A few examples are the following:

- Lith. and Skt. sūnus (son)

- Lith. and Skt. avis (sheep)

- Lith. dūmas and Skt. dhumas (smoke)

- Lith. antras and Skt. antaras (second, the other)

- Lith. vilkas and Skt. vrkas (wolf)

- Lith. ratas and Lat. rota (wheel)

- Lith. senis and Lat. senex (an old man)

- Lith. vyras and Lat. vir (a man)

- Lith. angis and Lat. anguis (a snake in Latin, a species of snakes in Lithuanian)

- Lith. linas and Lat. linum (flax, compare with English 'linen')

- Lith. ariu and Lat. aro (I plow)

- Lith. jungiu and Lat. iungeo (I join)

- Lith. gentys and Lat. gentes (tribes)

- Lith. mėnesis and Lat. mensis (month)

- Lith. dantys and Lat. dentes (teeth)

- Lith. naktys and Lat. noctes (nights)

- Lith. sėdime and Lat. sedemus (we sit)

This even extends to grammar, where for example Latin noun declensions ending in -um often correspond to Lithuanian -ų. Many of the words from this list share similarities with other Indo-European languages, including English.

On the other hand, the numerous lexical and grammatical similarities between Baltic and Slavic languages suggest an affinity between these two language groups. However, there exist a number of Baltic (particularly Lithuanian) words, notably those that are similar to Sanskrit or Latin, which lack counterparts in Slavic languages. This fact was puzzling to many linguists prior to the middle of the 19th century, but was later influential in the re-creation of the Proto Indo-European language. In any event, the history of the earlier relations between Baltic and Slavic languages and a more exact genesis of the affinity between the two groups remains in dispute.

Loan words

In a 1934 book entitled Die Germanismen des Litauischen. Teil I: Die deutschen Lehnwörter im Litauischen, K. Alminauskis found 2,770 loan words, of which about 130 were of uncertain origin. The majority of the loan words were found to have been derived from the Polish, Belarussian, and German languages, with some evidence that these languages all acquired the words from contacts and trade with Prussia during the era of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania.[6] Loan words comprised about 20% of the vocabulary used in the first book printed in the Lithuanian language in 1547, Martynas Mažvydas's Catechism.[7] The majority of loan words in the 20th century arrived from the Russian language.[8] Towards the end of the 20th century a number of English language words and expressions entered the spoken vernacular of city dwellers, especially the younger ones.[9]

The Lithuanian government has an established language policy which encourages the development of equivalent vocabulary to replace loan words.[10] However, despite the government's best efforts to avoid the use of loan words in the Lithuanian language, many English words have become accepted and are now included in Lithuanian language dictionaries. [11][12] In particular, words having to do with new technologies have permeated the Lithuanian vernacular, including such words as:

-

- monitorius (computer monitor)

- faksas (fax)

- kompiuteris (computer)

- failas (electronic file)

It is estimated that the number of foreign words, particularly of a technical nature, that have been adapted to the Lithuanian language might reach 70% or more.[13]

Other common foreign words have also been adopted by the Lithuanian language. Some of these include:

-

- taksi (taxi)

- pica (pizza)

- alkoholis (alcohol)

These words have been modified to suit the grammatical and phonetic requirements of the Lithuanian language, but their foreign roots are obvious.

Writing system

Like many of the Indo-European languages, Lithuanian employs a modified Roman script. It is composed of 32 letters. The collation order presents one surprise: "Y" is moved to occur between "Į" (I nosinė) and "J" because "Y" actually represents a prolonged /iː/.

| A | Ą | B | C | Č | D | E | Ę | Ė | F | G | H | I | Į | Y | J | K | L | M | N | O | P | R | S | Š | T | U | Ų | Ū | V | Z | Ž |

| a | ą | b | c | č | d | e | ę | ė | f | g | h | i | į | y | j | k | l | m | n | o | p | r | s | š | t | u | ų | ū | v | z | ž |

Lithuanian writing system is largely phonetical, i.e., one letter usually corresponds to a single phoneme. Nevertheless, there are a few exceptions, for example, the letter i represents either the sound similar to i in the English lit or softens the preceding consonant (iu = ü, io = ö, etc.).

Acute, grave, tilde and macron accents can be used to mark stress and vowel length. However, these are generally not written, except in dictionaries, grammars, and where needed for clarity. In addition, the following digraphs are used, but are treated as sequences of two letters for collation purposes. It should be noted that the "Ch" digraph represents a velar fricative, while the others are straightforward combinations of their component letters.

Dz dz [dz](dzė), Dž dž [dʒ](džė), Ch ch [x](cha).

Examples

- Lithuanian: Lietuviškai

- (language) lietuvių

- (nationality) lietuvis (masculine), lietuvė (feminine)

- Hello (informally): labas

- Goodbye (informally): iki!

- Please: prašau

- Thank you: ačiū

- That one: tas (masculine), ta (feminine)

- How much (does it cost)?: kiek kainuoja?

- Yes: taip

- No: ne

- Sorry: atsiprašau

- I don't understand: nesuprantu

- Do you speak English?: ar kalbate angliškai?

- Where is ...?: Kur yra ...?

- Tea: arbata

- Coffee: kava

- Milk: pienas

- How much? : Kiek?

- Example : pavyzdys

- Examples : pavyzdžiai

See also

- Martynas Mažvydas

- Lithuanian dictionaries

- Samogitian language

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 Ethnologue report for language code:lit

- ↑ Zinkevičius, Z. (1993). Rytų Lietuva praeityje ir dabar. Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidykla. pp. p.9. ISBN 5-420-01085-2. "...linguist generally accepted that Lithuanian language is the most archaic among live Indo-European languages...".

- ↑ Lithuanian Language. Encyclopedia Britannica.

- ↑ Lithuanian Language Encyclopedia (in Lithuanian), Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos inst., 1999. pp. 497 - 498. ISBN 5-420-01433-5

- ↑ Girdenis, Aleksas.Teoriniai lietuvių fonologijos pagrindai (The theoretical basics of the phonology of Lithuanian, in Lithuanian), 2nd Edition, Vilnius: Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos inst., 2003. pp. 222 - 232. ISBN 5-420-01501-3

- ↑ Ways of Germanisms into Lithuanian. N. Cepiene, Acta Baltico-Slavica, 2006

- ↑ Martynas Mažvydas' Language. Zigmas Zinkevičius, 1996. Accessed October 26, 2007.

- ↑ Slavic loanwords in the northern sub-dialect of the southern part of west high Lithuanian. V. Sakalauskiene, Acta Baltico-Slavica 2006. Accessed October 26, 2007.

- ↑ The Anglicization of Lithuanian. Antanas Kilmas, Lituanus, Summer 1994. Accessed October 26, 2007.

- ↑ State Language Policy Guidelines 2003–2008. Seimas of Lithuania, 2003. Accessed October 26, 2007.

- ↑ Dicts.com English to Lithuanian online dictionary

- ↑ LingvoSoft-Online-English-Lithuanian-Dictionary|Linvozone English to Lithuanian online dictionary

- ↑ Lithuanian Language discussion

- Leonardas Dambriūnas, Antanas Klimas, William R. Schmalstieg, Beginner's Lithuanian, Hippocrene Books, 1999, ISBN 0-7818-0678-X. Older editions (copyright 1966) called "Introduction to modern Lithuanian".

- Remys, Edmund, Review of Modern Lithuanian Grammar, Lithuanian Research and Studies Center, Chicago, 2nd revised edition, 2003.

- Klimas, Antanas. "Baltic and Slavic revisited". Lituanus vol. 19, no. 1, Spring 1973 . Retrieved on October 23, 2007.

- Zigmas Zinkevičius, "Lietuvių kalbos istorija" ("History of Lithuanian Language") Vol.1, Vilnius: Mokslas, 1984, ISBN 5-420-00102-0.

- Remys, Edmund, General distinguishing features of various Indo-European languages and their relationship to Lithuanian, Indogermanische Forschungen, Berlin, New York, 2007.

External links

- Lithuanian linguistics

- Ethnologue report for Lithuanian

- Academic Dictionary of Lithuanian

- Free English-Lithuanian traveler dictionary for print out

- Lithuanian English Dictionary from Webster's Online Dictionary - the Rosetta Edition

- Online Searchable Dictionary - searchable

- English-Lithuanian-German dictionaries and dialogues

- Lithuanian bilingual dictionaries

- The Historical Grammar of Lithuanian language

- Latvian and Lithuanian language with Japanese translation

- Summer School of Lithuanian at Vilnius University

- Learning Lithuanian in an online Lithuanian school

- Lithuanian Out Loud - Lithuanian lessons in a podcast series

- 2005 analysis of Indo-European lingustic relationships

- French-Lithuanian dictionary free online 36000 entries

- Lithuanian proverbs

|

|||||

|

|||||