Lithography

|

Part of the series on the |

||

| Woodblock printing | 200 CE | |

| Movable type | 1040 | |

| Intaglio | 1430s | |

| Printing press | 1439 | |

| Lithography | 1796 | |

| Chromolithography | 1837 | |

| Rotary press | 1843 | |

| Flexography | 1873 | |

| Mimeograph | 1876 | |

| Linotype typesetting | 1886 | |

| Offset press | 1903 | |

| Screen-printing | 1907 | |

| Dye-sublimation | 1957 | |

| Photocopier | 1960s | |

| Pad printing | 1960s | |

| Laser printer | 1969 | |

| Dot matrix printer | 1970 | |

| Thermal printer | ||

| Inkjet printer | 1976 | |

| 3D printing | 1986 | |

| Stereolithography | 1986 | |

| Digital press | 1993 | |

Lithography (from Greek λίθος - lithos, "stone" + γράφω - graphο, "to write") is a method for printing using a plate or stone with a completely smooth surface. By contrast, in intaglio printing plate is engraved (engraving), etched (etching) or stippled (mezzotint) to make cavities to contain the printing ink, and in woodblock printing and letterpress ink is applied to the raised surfaces of letters or images. Lithography uses oil or fat and gum arabic to divide the smooth surface into hydrophobic regions which reject the ink, and hydrophilic regions which accept it and thus become the background. Invented by Bavarian author Alois Senefelder in 1796,[1][2] it can be used to print text or artwork onto paper or another suitable material. Most books, indeed all types of high-volume text, are now printed using offset lithography, the most common form of printing production. The word "lithography" also refers to photolithography, a microfabrication technique used to make integrated circuits and microelectromechanical systems, although those techniques have more in common with etching than with lithography.

Contents |

The principle of lithography

Lithography uses chemical processes to create an image. For instance, the positive part of an image would be a hydrophobic chemical, while the negative image would be hydrophilic. Thus, when the plate is introduced to a compatible printing ink and water mixture, the ink will adhere to the positive image and the water will clean the negative image. This allows a flat print plate to be used, enabling much longer and more detailed print runs than the older physical methods of printing (e.g., intaglio printing, Letterpress printing).

Lithography was invented by Alois Senefelder in Bohemia in 1796. In the early days of lithography, a smooth piece of limestone was used (hence the name "lithography"—"lithos" (λιθος) is the ancient Greek word for stone). After the oil-based image was put on the surface, a solution of gum arabic in water, was applied, the gum sticking only to the non-oily surface. During printing, water adhered to the gum arabic surfaces and avoided the oily parts, while the oily ink used for printing did the opposite.

Lithography on limestone

Lithography works because of the mutual repulsion of oil and water. The image is drawn on the surface of the print plate with a fat or oil-based medium (hydrophobic), which may be in pigmented to make the drawing visible. A wide range of oil-based media is available, but the durability of the image on the stone depends on the lipid content of the material being used, and its ability to withstand water and acid. Following the drawing of the image, an aqueous solution of gum arabic, weakly acidified with nitric acid HNO3 is applied to the stone. The function of this solution is to create a hydrophilic layer of calcium nitrate salt, Ca(NO3)2, and gum arabic on all non-image surfaces. The gum solution penetrates into the pores of the stone, completely surrounding the original image with a hydrophilic layer that will not accept the printing ink. Using lithographic turpentine, the printer then removes any excess of the greasy drawing material, but a hydrophobic molecular film of it remains tightly bonded to the surface of the stone, rejecting the gum arabic and water, but ready to accept the oily ink.

When printing, the stone is kept wet with water. Naturally the water is attracted to the layer of gum and salt created by the acid wash. Printing ink based on drying oils such as linseed oil and varnish loaded with pigment is then rolled over the surface. The water repels the greasy ink but the hydrophobic areas left by the original drawing material accept it. When the hydrophobic image is loaded with ink, the stone and paper are run through a press which applies even pressure over the surface, transferring the ink to the paper and off the stone.

Senefelder had experimented in the early 1800s with multicolor lithography; in his 1819 book, he predicted that the process would eventually be perfected and used to reproduce paintings.[1] Multi-color printing was introduced through a new process developed by Godefroy Engelmann (France) in 1837 known as Chromolithography.[1] A separate stone was used for each colour, and a print went through the press separately for each stone. The main challenge was of course to keep the images aligned (in register). This method lent itself to images consisting of large areas of flat color, and led to the characteristic poster designs of this period.

The modern lithographic process

The earliest regular use of lithography for text was in countries using Arabic, Turkish and similar scripts, where books, especially the Qu'ran, were sometimes printed by lithography in the nineteenth century, as the links between the characters require compromises when movable type is used which were considered inappropriate for sacred texts.

High-volume lithography is used today to produce posters, maps, books, newspapers, and packaging — just about any smooth, mass-produced item with print and graphics on it. Most books, indeed all types of high-volume text, are now printed using offset lithography.

In offset lithography, which depends on photographic processes, flexible aluminum, polyester, mylar or paper printing plates are used in place of stone tablets. Modern printing plates have a brushed or roughened texture and are covered with a photosensitive emulsion. A photographic negative of the desired image is placed in contact with the emulsion and the plate is exposed to ultraviolet light. After development, the emulsion shows a reverse of the negative image, which is thus a duplicate of the original (positive) image. The image on the plate emulsion can also be created through direct laser imaging in a CTP (Computer-To-Plate) device called a platesetter. The positive image is the emulsion that remains after imaging. For many years, chemicals have been used to remove the non-image emulsion, but now plates are available that do not require chemical processing.

The plate is affixed to a cylinder on a printing press. Dampening rollers apply water, which covers the blank portions of the plate but is repelled by the emulsion of the image area. Ink, which is hydophobic, is then applied by the inking rollers, which is repelled by the water and only adheres to the emulsion of the image area--such as the type and photographs on a newspaper page.

If this image were directly transferred to paper, it would create a negative image and the paper would become too wet. Instead, the plate rolls against a cylinder covered with a rubber blanket, which squeezes away the water,picks up the ink and transfers it to the paper with accurate pressure. The paper rolls across the blanket drum and the image is transferred to the paper. Because the image is first transferred, or offset to the rubber drum, this reproduction method is known as offset lithography or offset printing. http://www.compassrose.com/static/Offset.jpg

Many innovations and technical refinements have been made in printing processes and presses over the years, including the development of presses with multiple units (each containing one printing plate) that can print multi-color images in one pass on both sides of the sheet, and presses that accommodate continuous rolls (webs) of paper, known as web presses. Another innovation was the continuous dampening system first introduced by Dahlgren instead of the old method which is still used today on older presses (conventional dampening), which are rollers covered in molleton (cloth) which absorbs the water. This increased control over the water flow to the plate and allowed for better ink and water balance. Current dampening systems include a "delta effect or vario " which slows the roller in contact with the plate, thus creating a sweeping movement over the ink image to clean impurities known as "hickies".

The advent of desktop publishing made it possible for type and images to be manipulated easily on personal computers for eventual printing on desktop or commercial presses. The development of digital imagesetters enabled print shops to produce negatives for platemaking directly from digital input, skipping the intermediate step of photographing an actual page layout. The development of the digital platesetter in the late twentieth century eliminated film negatives altogether by exposing printing plates directly from digital input, a process known as computer to plate printing.

Microlithography and nanolithography

Microlithography and nanolithography refer specifically to lithographic patterning methods capable of structuring material on a fine scale. Typically features smaller than 10 micrometers are considered microlithographic, and features smaller than 100 nanometers are considered nanolithographic. Photolithography is one of these methods, often applied to semiconductor manufacturing of microchips. Photolithography is also commonly used in fabricating MEMS devices. Photolithography generally uses a pre-fabricated photomask or reticle as a master from which the final pattern is derived.

Although photolithographic technology is the most commercially advanced form of nanolithography, other techniques are also used. Some, for example electron beam lithography, are capable of much higher patterning resolution (sometime as small as a few nanometers). Electron beam lithography is also commercially important, primarily for its use in the manufacture of photomasks. Electron beam lithography as it is usually practiced is a form of maskless lithography, in that no mask is required to generate the final pattern. Instead, the final pattern is created directly from a digital representation on a computer, by controlling an electron beam as it scans across a resist-coated substrate. Electron beam lithography has the disadvantage of being much slower than photolithography.

In addition to these commercially well-established techniques, a large number of promising microlithographic and nanolithographic technologies exist or are emerging, including nanoimprint lithography, interference lithography, X-ray lithography, extreme ultraviolet lithography, and scanning probe lithography. Some of these emerging techniques have been used successfully in small-scale commercial and important research applications.

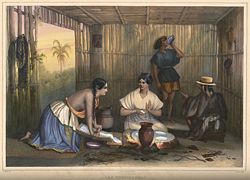

Lithography as an artistic medium

During the first years of the nineteenth century, lithography made only a limited impact on printmaking, mainly because technical difficulties remained to be overcome. Germany was the main centre of production during this period. Godefroy Engelmann, who moved his press from Mulhouse to Paris in 1816, largely succeeded in resolving the technical problems, and in the 1820s lithography was taken up by artists such as Delacroix and Géricault. London also became a centre, and some of Géricault's prints were in fact produced there. Goya in Bordeaux produced his last series of prints in lithography - The Bulls of Bordeaux of 1828. By the mid-century the initial enthusiasm had somewhat died down in both countries, although lithography continued to gain ground in commercial applications, which included the great prints of Daumier, published in newspapers. Rodolphe Bresdin and Jean-Francois Millet also continued to practice the medium in France, and Adolf Menzel in Germany.

In 1862 the publisher Cadart tried to launch a portfolio of lithographs by various artists which flopped, but included several superb prints by Manet. The revival began in the 1870s, especially in France with artists such as Odilon Redon, Henri Fantin-Latour and Degas producing much of their work in this way. The need for strictly limited editions to maintain the price had now been realized, and the medium become more accepted.

In the 1890s colour lithography became enormously popular with French artists, Toulouse-Lautrec most notably of all, and by 1900 the medium in both colour and monotone was an accepted part of printmaking, although France and the US have used it more than other countries. George Bellows, Alphonse Mucha, Pablo Picasso, Jasper Johns, David Hockney and Robert Rauschenberg are a few of the artists who have produced most of their prints in the medium. M.C. Escher is considered a master in lithography, and many of his prints were created using this process. More than other printmaking techniques, printmakers in lithography still largely depend on access to a good printer, and the development of the medium has been greatly influenced by when and where these have been established. See the List of Printmakers for more practitioners.

As a special form of lithography, the Serilith process is sometimes used. Serilith are mixed media original prints created in a process where an artist uses the lithograph and serigraph process. The separations for both processes are hand drawn by the artist. The serilith technique is used primarily to create fine art limited print editions.[3]

References

- ↑ 1.0 1.1 1.2 Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design. (1998) John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p 146 ISBN 0-471-291-98-6

- ↑ Carter, Rob, Ben Day, Philip Meggs. Typographic Design: Form and Communication, Third Edition. (2002) John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p 11

- ↑ What is a Serilith?

See also

- Photochrom

- Letterpress printing

- Block printing

- Flexography

- Etching (disambiguation)

- Color printing

- Lineography

- Rotogravure

- Typography

- Stereolithography

External links

- Åke Westins Ateljé, Swedish lithography artist

- Museum of Modern Art information on printing techniques and examples of prints

- The Invention of Lithography, Aloys Senefelder, (Eng. trans. 1911)(a searchable facsimile at the University of Georgia Libraries; DjVu and layered PDF format)

- Theo De Smedt's website, author of "What's lithography"

- Extensive information on Honoré Daumier and his life and work, including his entire output of lithographs

- Digital work catalog to 4000 lithographs and 1000 wood engravings

- Detailed examination of the processes involved in the creation of a typical scholarly lithographic illustration in the 19th century

- Nederlands Steendrukmuseum

- Delacroix's Faust lithographs at the Davison Art Center, Wesleyan University