Treaty of Lisbon

| Treaty of Lisbon amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community |

|

|---|---|

| Type of treaty | Amender of previous treaties |

| Drafted | 7–8 September 2007 |

| Signed - location |

13 December 2007 Lisbon, Portugal |

| Sealed | 18 December 2007 |

| Effective - condition |

1 January 2009 or later ratified by all Member States |

| Signatories | EU Member States |

| Depositary | Government of Italy |

| Languages | 23 EU languages |

| Website | europa.eu/lisbon_treaty |

| Wikisource original text: Treaty of Lisbon |

|

The Treaty of Lisbon (also known as the Reform Treaty) is a treaty designed to streamline the workings of the European Union (EU) with amendments to the Treaty on European Union (TEU, Maastricht) and the Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC, Rome), the latter being renamed Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union (TFEU) in the process. The stated aim of the treaty is "to complete the process started by the Treaty of Amsterdam and by the Treaty of Nice with a view to enhancing the efficiency and democratic legitimacy of the Union and to improving the coherence of its action."[1]

Prominent changes introduced with the Treaty of Lisbon include more qualified majority voting in the EU Council, increased involvement of the European Parliament in the legislative process through extended codecision with the EU Council, reduction of the number of Commissioners from 27 to 18, eliminating the pillar system, and the creation of a President of the European Union and a High Representative for Foreign Affairs to present a united position on EU policies. If ratified, the Treaty of Lisbon would also make the Union's human rights charter, the Charter of Fundamental Rights, legally binding.

The negotiations on modifying the EU institutions began in 2001, first resulting in the European Constitution, which failed due to rejection in two referendums. The Treaty of Lisbon was signed on 13 December 2007 in Lisbon (as Portugal held the EU Council's Presidency at the time), and was planned to have been ratified in all member states by the end of 2008, so it could come into force before the 2009 European elections. 25 of the total 27 member states have completed the ratification. However, the rejection of the Treaty on 12 June 2008 by the Irish electorate means that the treaty cannot currently come into force.[2]

History

Background

- Further information: History of the European Constitution

The need to review the EU's constitutional framework, particularly in light of the accession of ten new Member States in 2004, was highlighted in a declaration annexed to the Treaty of Nice in 2001. The agreements at Nice had paved the way for further enlargement of the Union by reforming voting procedures. The Laeken declaration of December 2001 committed the EU to improving democracy, transparency and efficiency, and set out the process by which a constitution aiming to achieve these aims could be created. The European Convention was established, presided over by former French President Valéry Giscard d'Estaing, and was given the task of consulting as widely as possible across Europe with the aim of producing a first draft of the Constitution. The final text of the proposed Constitution was agreed upon at the summit meeting on 18–19 June 2004 under the presidency of Ireland.

The Constitution, having been agreed by heads of government from the 25 Member States, was signed at a ceremony in Rome on 29 October 2004. Before it could enter into force, however, it had to be unanimously ratified by each member state. Ratification took different forms in each country, depending on the traditions, constitutional arrangements, and political processes of each country. In 2005, referendums held in the Netherlands and France rejected the European Constitution. While the majority of the Member States already had ratified the European Constitution (mostly through parliamentary ratification, although Spain and Luxembourg held referendums), due to the requirement of unanimity to amend the constitutional treaties of the EU, it became clear that it could not enter into force. This led to a "period of reflection" and the political end of the proposed European Constitution.

New impetus

In 2007, Germany took over the rotating EU Presidency and declared the period of reflection over. By March, the 50th anniversary of the Treaties of Rome, the Berlin Declaration was adopted by all Member States. This declaration outlined the intention of all Member States to agree on a new treaty in time for the 2009 Parliamentary elections, that is to have a ratified treaty before mid-2009.[3]

Already before the Berlin Declaration, the Amato Group (officially the Action Committee for European Democracy, ACED) – a group of European politicians, backed by the Barroso Commission with two representatives in the group – worked unofficially on rewriting the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe (EU Constitution). On 4 June 2007, the group released their text in French – cut from 63,000 words in 448 articles in the Treaty establishing a Constitution for Europe to 12,800 in 70 articles.[4] In the Berlin Declaration, the EU leaders unofficially set a new timeline for the new treaty;

Timetable

- 21–23 June 2007: European Council meeting in Brussels, mandate for IGC

- 23 July 2007: Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) in Lisbon, text of Reform Treaty

- 7–8 September 2007: Foreign Ministers’ meeting

- 18–19 October 2007: European Council in Lisbon, final agreement on Reform Treaty

- 13 December 2007: Signing in Lisbon

- 1 January 2009: Intended date of entry into force

June European Council

On 21 June 2007, the European Council of heads of states met in Brussels to agree upon the foundation of a new treaty to replace the rejected Constitution. The meeting took place under the German Presidency of the EU Council, with Chancellor Angela Merkel leading the negotiations as President-in-Office of the European Council. After the Council quickly dealt with its other business, such as deciding on the accession of Cyprus and Malta to the Eurozone, negotiations on the Treaty took over and lasted until the morning of 23 June 2007. The hardest part of the negotiations was reported to be Poland's insistence on 'square root' voting in the EU Council.[5]

Agreement was reached on a 16-page mandate for an Intergovernmental Conference, that proposed removing much of the constitutional terminology and many of the symbols from the old European Constitution text. In addition it was agreed to recommend to the IGC that the provisions of the old European Constitution should be amended in certain key aspects (such as voting or foreign policy). Due to pressure from the United Kingdom and Poland, it was also decided to add a protocol to the Charter of fundamental human rights within the EU (clarifying that it did not extend the rights of the courts to overturn domestic law in Britain or Poland). Among the specific changes were greater ability to opt-out in certain areas of legislation and that the proposed new voting system that was part of the European Constitution would not be used before 2014 (see Provisions below).[6]

In the June meeting, the name 'Reform Treaty' also emerged, finally clarifying that the Constitutional approach was abandoned. Technically it was agreed that the Reform Treaty would amend both the Treaty on European Union (TEU) and the Treaty establishing the European Community (TEC) to include most provisions of the European Constitution, however not to combine them into one document. It was also agreed to rename the Treaty establishing the European Community, which is the main functional agreement including most of the substantive provisions of European primary law, to "Treaty on the Functioning of the Union". In addition it was agreed, that unlike the European Constitution where a Charter was part of the document, there would only be a reference to the Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union to make that text legally binding.[6]After the council, Poland indicated they wished to re-open some areas. During June, Poland's Prime Minister had controversially stated that Poland would have a substantially larger population were it not for World War II.[7] Another issue was that Dutch prime minister Jan-Peter Balkenende succeeded in a greater role for national parliaments in the EU decision making process, as he declared this to be non-negotiable for Dutch agreement.[8]

Intergovernmental Conference

Portugal had pressed and supported Germany to reach an agreement on a mandate for an Intergovernmental Conference (IGC) under their presidency. After the June negotiations and final settlement on a 16-page framework for the new Reform Treaty, the Intergovernmental conference on actually drafting the new treaty commenced on 23 July 2007. The IGC opened following a short ceremony. The Portuguese presidency presented a 145 page document (with an extra 132 pages of 12 protocols and 51 declarations) entitled the 'Draft Treaty amending the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community' and made it available on the Council of the European Union website as a starting point for the drafting process.[9]

In addition to government representatives and legal scholars from each member state, the European Parliament sent three representatives. These were conservative Elmar Brok, social democratic Enrique Baron Crespo and liberal Andrew Duff.[10]

Before the opening of the IGC, the Polish government expressed a desire to renegotiate the June agreement, notably over the voting system, but relented under political pressure by most other Member States, due to a desire not to be seen as the sole trouble maker over the negotiations.[11]

October European Council

The October European Council, led by Portugal's Prime Minister and then President-in-Office of the European Council, José Sócrates, consisted of legal experts from all Member States scrutinising the final drafts of the Treaty. During the council, it became clear that the Reform Treaty would be called Treaty of Lisbon because its signing would take place in Lisbon, Portugal being the holder of Council presidency at the time.

At the European Council meeting on 18 October and 19 October 2007 in Lisbon, a few last-minute concessions were made to ensure the signing of the treaty.[12] That included giving Poland a slightly stronger wording for the revived Ioannina Compromise, plus a nomination for an additional Advocate General at the European Court of Justice. The creation of the permanent "Polish" Advocate General was formally permitted by an increase of the number of Advocates General from 8 to 11.[13]

Signing

The treaty was signed 13 December 2007 by heads of government for Member States in the Jerónimos Monastery in Lisbon, Portugal. British Prime Minister Gordon Brown did not take part in the main ceremony, instead signing the treaty separately a number of hours after the other delegates. A requirement to appear before a committee of British MPs was cited as the reason for his absence.[14]

Ratification

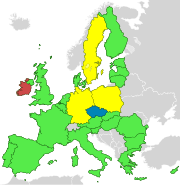

Deposited: 23 countries Ratified, not yet deposited: Germany and Poland Pending: Czech Republic Unauthorised: Ireland

In order to enter into legal force, the Treaty of Lisbon must be ratified in all Member States. If this does not happen as scheduled by the end of 2008, the Treaty will come into force on the first day of the month following the last ratification.[15]

Most states have or will ratify in parliamentary processes. The Irish government decided to put the matter to a referendum on the basis of legal advise that to do otherwise would violate the Irish Constitution. This arose from a 1987 Irish Supreme Court decision that ruled that significant changes to the European Union treaties needed to be authorised by an amendment to the Irish Constitution, always done by referendum. The Irish referendum on the Lisbon Treaty resulted in its rejection by 53.4% of those who voted, against 46.6% for. There were unsuccessful calls to governments to hold referendums in some other member states.

Hungary was the first to ratify the Treaty of Lisbon on 17 December 2007. Since that date, the number of Member States that have completed the ratification has risen to 25 of the total 27, and the number of Member States that have deposited their ratification with the Government of Italy, which is the final step needed in order for the Treaty of Lisbon to enter into force, to 23.[16]

At a glance

| Signatory | Conclusion date | Chamber | AB | Deposited[16] | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 9 April 2008 | National Council | 151 | 27 | 5 | 13 May 2008 | [17] | |

| 24 April 2008 | Federal Council | 58 | 4 | 0 | [18] | ||

| 28 April 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [19] | ||||

| 6 March 2008 | Senate | 48 | 8 | 1 | 15 October 2008 | [20] | |

| 10 April 2008 | Chamber of Representatives | 116 | 11 | 7 | [21] | ||

| 19 June 2008 | Royal Assent | Granted | [22] | ||||

| 14 May 2008 | Walloon Parliament (regional) (community matters) |

56 | 2 | 4 | [23] | ||

| 14 May 2008 | 53 | 3 | 2 | [24] | |||

| 19 May 2008 | German-speaking Community | 22 | 2 | 1 | [25] | ||

| 20 May 2008 | French Community | 67 | 0 | 3 | [26] | ||

| 27 June 2008 | Brussels Regional Parliament | 65 | 10 | 1 | [27] | ||

| 27 June 2008 | Brussels United Assembly | 66 | 10 | 0 | [28] | ||

| 10 July 2008 | Flemish Parliament (regional) (community matters) |

76 | 21 | 2 | [29] | ||

| 78 | 22 | 3 | [29] | ||||

| 11 July 2008 | COCOF Assembly | 52 | 5 | 0 | [30] | ||

| 21 March 2008 | National Assembly | 195 | 15 | 30 | 28 April 2008 | [31] | |

| 3 July 2008 | House of Representatives | 31 | 17 | 1 | 26 August 2008 | [32] | |

| Unknown | Presidential Assent | Granted | [33] | ||||

| 9 December 2008 | Chamber of Deputies | [34] | |||||

| 10 December 2008 | Senate | [35] | |||||

| TBD | Presidential Assent | ||||||

| 24 April 2008 | Parliament | 90 | 25 | 0 | 29 May 2008 | [36] | |

| 30 April 2008 | Royal Assent | Granted | [37] | ||||

| 11 June 2008 | Parliament | 91 | 1 | 9 | 23 September 2008 | [38] | |

| 19 June 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [39] | ||||

| 11 June 2008 | Parliament | 151 | 27 | 21 | 30 September 2008 | [40] | |

| 12 September 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [41] | ||||

| 7 February 2008 | National Assembly | 336 | 52 | 22 | 14 February 2008 | [42] | |

| 7 February 2008 | Senate | 265 | 42 | 13 | [43] | ||

| 13 February 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [44] | ||||

| 24 April 2008 | Federal Diet | 515 | 58 | 1 | [45][46] | ||

| 23 May 2008 | Federal Council | 65 | 0 | 4 | [47][48] | ||

| 8 October 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [49] | ||||

| 11 June 2008 | Parliament | 250 | 42 | 8 | 12 August 2008 | [50] | |

| 17 December 2007 | National Assembly | 325 | 5 | 14 | 6 February 2008 | [51] | |

| 20 December 2007 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [52] | ||||

| 29 April 2008 | Dáil Éireann | Passed | [53] | ||||

| 9 May 2008 | Seanad Éireann | Passed | [53] | ||||

| 12 June 2008 | Referendum* | 46%* | 53%* | N/A* | [53] | ||

| TBD | Presidential Assent | ||||||

| 23 July 2008 | Senate of the Republic | 286 | 0 | 0 | 8 August 2008 | [54] | |

| 31 July 2008 | Chamber of Deputies | 551 | 0 | 0 | [55] | ||

| 2 August 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [56] | ||||

| 8 May 2008 | Parliament | 70 | 3 | 1 | 16 June 2008 | [57] | |

| 28 May 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | |||||

| 8 May 2008 | Parliament | 83 | 5 | 23 | 26 August 2008 | [58] | |

| 14 May 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [59] | ||||

| 29 May 2008 | Chamber of Deputies | 47 | 1 | 3 | 21 July 2008 | [60] | |

| 3 July 2008 | Ducal Assent | Granted | [61] | ||||

| 29 January 2008 | House of Representatives | 65 | 0 | 0 | 6 February 2008 | [62] | |

| 5 June 2008 | Second Chamber | 111 | 39 | 0 | 11 September 2008 | [63] | |

| 8 July 2008 | First Chamber | 60 | 15 | 0 | [64] | ||

| 10 July 2008 | Royal Assent | Granted | [65] | ||||

| 1 April 2008 | House of Representatives | 384 | 56 | 12 | [66] | ||

| 2 April 2008 | Senate | 74 | 17 | 6 | [67] | ||

| 9 April 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [68] | ||||

| 23 April 2008 | Assembly of the Republic | 208 | 21 | 0 | 17 June 2008 | [69] | |

| 9 May 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [70] | ||||

| 4 February 2008 | Parliament | 387 | 1 | 1 | 11 March 2008 | [71][72] | |

| 7 February 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [73] | ||||

| 10 April 2008 | National Council | 103 | 5 | 1 | 24 June 2008 | [74][75] | |

| 12 May 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | [76] | ||||

| 29 January 2008 | National Assembly | 74 | 6 | 0 | 24 April 2008 | [77] | |

| 7 February 2008 | Presidential Assent | Granted | |||||

| 26 June 2008 | Congress of Deputies | 322 | 6 | 2 | 8 October 2008 | [78] | |

| 15 July 2008 | Senate | 232 | 6 | 2 | [79] | ||

| 30 July 2008 | Royal Assent | Granted | [80] | ||||

| 20 November 2008 | Parliament | 243 | 39 | 13 | 3 December 2008 | [81][82] | |

| 11 March 2008 | House of Commons | 346 | 206 | 81 | 16 July 2008 | [83][84] | |

| 18 June 2008 | House of Lords | Content | [85] | ||||

| 19 June 2008 | Royal Assent | Granted | [86][87] | ||||

| *Turnout: 53.13% (1,621,037 votes) | |||||||

| *752,451 votes (46.4%) "YES"-votes, 862,415 votes (53.2%) "NO"-votes and 6,171 votes (0.4%) spoilt | |||||||

Consultative votes

The European Parliament and some special territories of EU Member States carry out votes on the treaties. While with respect to these territories a rejection would result in the treaty not applying to the territory in question, such a vote does not affect the overall ratification process. Therefore, the treaty could come into force whether these territories approve or reject the treaty.

| Territory | Conclusion date | Chamber | AB | Ref. | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TBD | Åland Parliament | [88][89] | ||||

| TBD | Gibraltar Parliament | [90] | ||||

| 20 February 2008 | European Parliament | 525 | 115 | 29 | [91][92] |

Specific issues

Czech Republic

Current Czech President, Václav Klaus opposes ratifying the Lisbon Treaty and has called the process to be brought to an end.[93] He has also stated that he would not sign the treaty unless Ireland had ratified before.[94][95]

Under the Czech Constitution ratification requires a presidential signature, though some believe it is unlikely to be withheld should both houses of parliament approve the treaty.[96] The Czech prime minister Mirek Topolánek stated that there is no way for the treaty to be ratified before the end of 2008.[97]

Finland - Åland Islands

The Åland Islands, an autonomous region in Finland, will vote on the Treaty in the regional parliament. A two-thirds majority of the given votes will be required for the Treaty to be accepted. The process has begun, but no date for the vote has yet been set.

The regional (Åland) and the central (Finland) government are currently negotiating how EU-related issues concerning Åland will be treated in the future. The Åland government has put forward four requests that will have to be resolved before accepting the Treaty:

- An own seat in the European Parliament.

- Right to appear before the European Court of Justice (currently Åland is represented by Finland).

- Participation in the control of the principle of subsidiarity.

- Participation in the meetings of the Council.

At a press conference on 2 September 2008, the Åland government presented the current outcome of the negotiations:[98]

- No seat in the European Parliament for now.

- The right to appear in court and the control of the principle of subsidiarity will be added to the autonomy law.

- The representation in the Council is already possible with the current autonomy law, but will be more formalized.

- A new document of principles regarding EU issues will be written.

No changes in the Treaty itself have been proposed. A rejection of the Treaty on Åland would not prevent it in the rest of Finland and the Union.

Finland is set to lose one Member of European Parliament in accordance with both the Treaties of Nice and Lisbon.[99] Åland wishes to maintain their own representative in the European Parliament but this would give the island a disproportionate amount of voter influence, with a value of 30 (relative to Germany), whereas Finland as a whole currently only has a relative influence of 2.[100]

Ireland

- Further information: Twenty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland Bill, 2008

Following a 1987 decision of the Supreme Court of Ireland, international treaties that might be in conflict with the Constitution of Ireland require the assent of the people to amend it so as to permit ratification. Any such amendment needs to be put to a public vote. Thus Ireland was the only Member State that held a referendum on the Treaty of Lisbon, in addition to a parliamentary vote.

All members from the three government parties in the Oireachtas supported the 'Yes' campaign. So did all opposition parties in the parliament, with the exception of Sinn Féin.[101] The Green Party, whilst being a party in the government, did not officially take a line, having failed to reach a two-thirds majority either way at a party congress in January 2008, leaving members free to decide. Most Irish trade unions and business organisations supported the 'yes'-campaign also. Those campaigning for the 'No' vote included political party Sinn Féin, lobby group Libertas and the People Before Profit Alliance.[102]

The result of the referendum on 12 June 2008 was in opposition to the treaty, with 53.4% against the Treaty and 46.6% in favour, in a 53.1% turnout.[103] A week later, Eurobarometer conducted hours after the vote was released,[104] indicating why the electorate voted as they did. 10 September, the government published the more in-depth research analysis on voters' states reasons for voting yes or no.[105]

First plans for a revote appeared in July 2008: The term of the current European Commission would be extended until the Lisbon Treaty comes into force, member states would agree not to reduce the number of Commissioners and Ireland would hold another vote in September or October 2009 after receiving guarantees on abortion, taxation and military neutrality.[106] In a widely-publicised policy paper, published in October 2008, EU specialist Dr. John O'Brennan argued that, presuming that all other 26 member states ratified the Treaty by early 2009, the Irish government would have no option but to hold a second referendum. But the issue will be whether Ireland remains a member of the EU or voluntarily departs.[107] In November 2008 the Irish Foreign Minister Micheal Martin told his parliamentary Subcommittee on Ireland's Future in the European Union that there was "no question" of Ireland's EU partners putting pressure on its government, and that: "There is an appreciation that the result of the referendum reflected serious and genuinely held concerns".[108]

Germany

German ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon was placed on hold on June 30, 2008.[109] While parliamentary ratification has been completed, formal ratification requires the signature of the President, which has been withheld pending a ruling from the Constitutional Court on its compatibility with the Basic Law, Germany's constitution.[110] Which followed a challenge launched by German MP Peter Gauweiler a member of Bavaria's Christian Social Union (CSU), who sits in the Bundestag, claiming the treaty unconstitutional. Mr. Gauweiler launched a similar challenge to the European Constitution in 2005 but after its failure the Constitutional Court made no ruling and a presidential signature was never given. [111]

In October 2008 Germany's president Horst Köhler has signed the German law which prepares the implementation of the treaty on a national level and has agreed to sign the instruments of ratification of the treaty, but will wait to sign and deposit it in Rome until the Constitutional Court has given its approval, which is expected to take place in 2009.[112]

Poland

Ratification in Poland was stalled while awaiting presidential signature (so-called "ratification act"). The President, by that point, did sign the bill which allows him to ratify the treaty[113] (in that bill the procedure for granting consent to ratification was chosen according to Article 90.4 of the Polish constitution.[114]). It did not mean that he finished the ratification of the treaty.[115] The President is not obliged to ratify the treaty.

The president, Lech Kaczyński, has yet to give his final signature and has cited that it would be pointless to do so before a solution to the Irish no vote is found.[116] This situation is generally attributed to a domestic dispute between the two major political parties PO (the current government) and PiS (the presidential party). The PiS want the PO to enact a new law which would oblige the government to consider the opinion of the president and parliament before every summit of the European Council.

The president has come under increasing pressure from the French Presidency to ratify the treaty with President Sarkozy reminding him that he originally negotiated the treaty.

Function

binding basis

of Lisbon

binding basis

In line with the nature of most amending treaties, the Treaty of Lisbon is not intended to be read as an autonomous text. It consists of a number of amendments to the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty establishing the European Community, the latter being renamed 'Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union' in the process. The Treaty on European Union would, after being amended by the Treaty of Lisbon, provide a reference to the EU's Charter of Fundamental Rights, making that document legally binding. The Treaty on European Union, the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union and the Charter of Fundamental rights would have equal legal value and combined constitute the European Union's legal basis.

A typical amendment in Treaty of Lisbon text is:

| “ | Article 7 shall be amended as follows:

(a) throughout the Article, the word "assent" shall be replaced by "consent", the reference to breach "of principles mentioned in Article 6(1)" shall be replaced by a reference to breach "of the values referred to in Article 2" and the words "of this Treaty" shall be replaced by "of the Treaties"; |

” |

Fundamental Rights Charter

The fifty-five articles of the Charter of Fundamental Rights list political, social and economic rights for EU citizens. It is intended to make sure that European Union regulations and directives do not contradict the European Convention on Human Rights which is ratified by all EU Member States (and to which the EU as a whole would accede under the Treaty of Lisbon[9]). In the rejected EU Constitution it was integrated into the text of the treaty and was legally binding. The UK, as one of the two countries with a common law legal system in the EU[117] and a largely uncodified Constitution, was against making it legally binding over domestic law.[118] The suggestion by the German presidency that a single reference to it with a single article in the amended treaties, maintaining that it should be legally binding, was implemented.[119] Nevertheless, in an attached protocol, Poland and the United Kingdom have opt-outs from these provisions of the treaty. Article 6 of the Treaty on European Union elevates the Charter to the same legal value as the Treaty on European Union and the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union.

Amendments

Summary |

|

|

|

Central Bank

- Further information: European Central Bank

The European Central Bank would become an official institution. The Treaty of Lisbon would declare the euro to be the official currency of the Union, although in practice not affecting the current Eurozone enlargement process or national opt-outs of the monetary union.

Court of Justice

- Further information: European Court of Justice

The Treaty of Lisbon renames the Court of Justice of the European Communities the 'Court of Justice of the European Union'.

A new 'emergency' procedure will be introduced into the preliminary reference system, which will allow the Court of Justice to act "with the minimum of delay" when a case involves an individual in custody.[120]

The ECJ's jurisdiction will continue to be excluded from matters of foreign policy, though it will have new jurisdiction to review foreign policy sanction measures.[121] It will also have jurisdiction over certain 'Area of Freedom, Security and Justice' (AFSJ) matters not concerning policing and criminal cooperation.[122]

Court of First Instance

- Further information: Court of First Instance

The Court of First Instance would be renamed the 'General Court'.

Council

- Further information: Council of the European Union

The Council of the European Union will still be an organised platform of meetings between national ministers of specific departments (e.g. finance- or foreign ministers). Legislative procedural meetings that include debate and voting will be held in public (televised).

The Treaty of Lisbon would expand the use of qualified majority voting (QMV), by making it the standard voting procedure. Though some areas of policy still require unanimous decisions (notably in foreign policy, defence and taxation). QMV is reached when a majority of all member countries (55%) who represent a majority of all citizens (65%) vote in favour of a proposal. When the Council is not acting on a proposal of the Commission, the necessary majority of all member countries is increased to 72% while the population requirement stays the same. To block legislation at least 4 countries have to be against the proposal.

The current Nice treaty voting rules that include a majority of countries (50% / 67%), voting weights (74%) and population (62%) would remain in place until 2014. Between 2014 and 2017 a transitional phase would take place where the new qualified majority voting rules apply, but where the old Nice treaty voting weights can be applied when a member state wishes so. Also from 2014 a new version of the 1994 "Ioannina Compromise" would take effect, which allows small minorities of EU states to call for re-examination of EU decisions they do not like.[123]

Presidency of the Council

- Further information: Presidency of the Council of the European Union

The Council would have an 18-month rotating Presidency shared by a trio of Member States, with the purpose of providing more continuity. The exception would be the Council's Foreign Affairs configuration, which would be chaired by the newly created post of Representative for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy.

European Council

- Further information: European Council

The European Council of national heads of government or heads of state (either the prime minister or the president), will officially be separated from the Council of the European Union (national ministers for specific areas of policy).

President of the European Council

- Further information: President of the European Council

|

|

The current post of President-in-Office of the European Council is loosely defined, with the Union's treaties stating only that the European Council shall be chaired by the head of government (or state) of the country holding the presidency of the European Union which rotates every six months.[125] If ratified the new President of the European Council would be elected for a two and a half year term. The election would take place by a qualified majority among the members of the body, and the President can be removed by the same procedure. Unlike the President of the European Commission, there is no approval from the European Parliament.[126]

The President's work would be largely administrative in coordinating the work of the Council and organising the meeting. It does however offer external representation of the council and the Union and reports to the European Parliament after Council meetings and at the beginning and end of his or her term.

In many newspapers this new post is inaccurately being called "President of Europe".[127][128]

Parliament

- Further information: European Parliament

The legislative power and relevance of the directly elected European Parliament would, under the provisions of the Treaty of Lisbon, be increased by extending co-decision procedure with the Council to new areas of policy. This procedure would become the ordinary legislative procedure in the work of the Council and the Parliament.

In the few remaining areas (currently called "special legislative procedures"), Parliament either has the right of consent to a Council measure, or vice-versa, except where the few cases where the old Consultation procedure applies (where the Council must consult the European Parliament before voting on the Commission proposal and take its views into account. It is not bound by the Parliament's position but only by the obligation to consult it. Parliament must be consulted again if the Council deviates too far from the initial proposal).

The number of MEPs would be permanently reduced to 750, in addition to the President of the Parliament. If the treaty does not come into effect before 2009, the number of MEPs will be permanently reduced to 732 according to the Treaty of Nice. The Lisbon treaty also reduces the maximum number of MEPs from each member state from 99 to 96 (applies to Germany) and increases the minimal number from 5 to 6 (applies to Estonia, Cyprus, Luxembourg and Malta).

The Parliament also gains greater powers over the entirety of the EU budget, and its competence is extended from 'obligatory' expenditure to include the budget in its entirety. On the other hand, the Commission would not longer be obliged to submit a preliminary draft budget to the Council, but to submit the budget proposal directly.

National parliaments

The Treaty of Lisbon expands the role of Member States' parliaments in the work and legislative processes of the EU institutions and bodies.

Greater role in responding to new applications for membership (new Article 34 replacing Article 49). National parliaments would be able to veto measures furthering judicial cooperation in civil matters (new Article 69d).

Article 8c says among other things that national parliaments are to contribute to the good functioning of the Union:

-

- through being informed by, and receive draft legislation from Union institutions.

- by seeing to it that the principle of subsidiarity is respected.

- by taking part in the evaluation mechanisms for the implementation of the Union policies in the area of freedom, security and justice.

- through being involved in the political monitoring of Europol and the evaluation of Eurojust's activities.

- by being notified of applications for EU accession.

- by taking part in the inter-parliamentary cooperation between national parliaments and with the European Parliament.

Protocol 2 provides for a greater role of national parliaments in ensuring that EU measures comply with the principle of subsidiarity. In comparison with the proposed Constitution, the Reform Treaty allows national parliaments eight rather than six weeks to study European Commission legislative proposals and decide whether to send a reasoned opinion stating why the national parliament considers it to be incompatible with subsidiarity. National parliaments may vote to have the measure reviewed. If one third (or one quarter, where the proposed EU measure concerns freedom, justice and security) of national parliaments are in favour of a review, the Commission would have to review the measure and if it decides to maintain it, must give a reasoned opinion to the Union legislator as to why it considers the measure to be compatible with subsidiarity.

Commission

The Commission of the European Communities would officially be renamed 'European Commission'.[9]

The Treaty of Lisbon would reduce the size of the Commission from the present 27 Commissioners to 18. That would end the arrangement of having at least one for each Member State at all times, which has existed since 1957. Commissioners are appointed for five year terms. The new system would mean that for five years in any fifteen year cycle, each country (regardless of size) would be without a commissioner. The reason for lowering the number of commissioners is that there are not enough tasks for 27, and increased effectiveness.

The person holding the new post of 'High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy' would automatically also be a Vice-President of the Commission.

Foreign relations

The changes in foreign relations have been seen by some as the core changes in the treaty, in the same way as the Single European Act created a single market, the Maastricht Treaty created the euro, or the Treaty of Amsterdam created greater cooperation in justice and home affairs.[129] Foreign Relations is a policy area which under the Treaty of Lisbon still would require unanimity in the European Council.

Foreign High Representative

|

|

The Treaty would merge the post of High Representative for the Common Foreign and Security Policy (currently held by Javier Solana) with the European Commissioner for External Relations and European Neighbourhood Policy (currently held by Benita Ferrero-Waldner), creating a 'High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy' in an effort to reduce the number of Commissioners, and coordinate the Union's foreign policy with greater consistency. The new High Representative would also become a Vice-President of the Commission, the administrator of the European Defence Agency and the Secretary-General of the Council. He or she would also get an External Action Service and a right to propose defence or security missions. The Constitution called this post the 'Union Foreign Minister'.[6][130]

Several Member States feared that this post would undermine their national foreign policy, so the EU summit mandated that the IGC would agree to the following Declaration:

| “ | [...]the provisions covering Common Foreign and Security Policy (CFSP) including in relation to the (new) High Representative would not affect the existing legal basis, responsibilities, and powers of each Member State in relation to the formulation and conduct of its foreign policy, its national diplomatic service, relations with third countries and participation in international organisations, including a Member State's membership of the UN Security Council.

The Conference also notes that the provisions covering CFSP do not give new powers to the Commission to initiate decisions or increase the role of the European Parliament. The Conference also recalls that the provisions governing the CFSP do not prejudice the specific character of the security and defence policy of the Member States. |

” |

|

—Presidency conclusions[6] |

||

Legal personality and pillar consolidation

- See also: Legal person and Three pillars of the European Union

Under the existing treaties, only the European Communities pillar has its own legal personality. Under the new provisions, the three pillars would be merged into one legal personality called the European Union. The Treaty on European Union would after the Treaty of Lisbon state that "The Union shall replace and succeed the European Community." Hence, the existing names of EU institutions would have the word 'Community' removed (e.g. the de facto title 'European Commission' would become official, replacing its treaty name of 'Commission of the European Communities'.)[9]

This merger of the pillars, including the European Community, would partly finalise the progress of establishing various communities and treaty-bodies, that has been going on since around the 1950s. The defence body of Western European Union (WEU) would effectively also be absorbed by the EU, through the European Defence Agency, which would gain a legal role under the Lisbon Treaty.

| 1948 Brussels |

1952 Paris |

1958 Rome |

1967 Brussels (founded EC) |

1987 SEA |

1993 Maastricht (founded EU) |

1999 Amsterdam |

2003 Nice |

2009? Lisbon |

|

| European Atomic Energy Community (EURATOM) | |||||||||

| European Coal and Steel Community (ECSC) | European Union (EU) | ||||||||

| European Economic Community (EEC) | → P I L L A R S → |

European Community (EC) | |||||||

| ↑European Communities↑ | Justice & Home Affairs (JHA) | ||||||||

| Police & Judicial co-operation in Criminal Matters (PJCC) | |||||||||

| European Political Cooperation (EPC) | Common Foreign & Security Policy (CFSP) | ||||||||

| Western European Union (WEU) | |||||||||

Defined policy areas

In the Lisbon Treaty the distribution of competences in various policy areas between Member States and the Union is explicitly stated in the following three categories:

|

Exclusive competence

The Union has exclusive competence to make directives and conclude international agreements when provided for in a Union legislative act.

|

Shared competence

Member States cannot exercise competence in areas where the Union has done so.

|

Supporting competence

The Union can carry out actions to support, coordinate or supplement Member States' actions.

|

Enlargement and secession

- Further information: Enlargement of the European Union

A proposal to enshrine the Copenhagen Criteria for further enlargement in the treaty was not fully accepted as there were fears it would lead to Court of Justice judges having the last word on who could join the EU, rather than political leaders.[130]

The treaty introduces an exit clause for members wanting to withdraw from the Union. This formalises the procedure by stating that a member state must inform the European Council before it can terminate its membership. While there has been one instance where a territory has ceased to be part of the Community (Greenland in 1985), there is currently no regulated opportunity to exit the European Union.

A new provision in the Treaty of Lisbon is that the status of French, Dutch and Danish overseas territories can be changed more easily, by no longer requiring a full treaty revision. Instead, the European Council may, on the initiative of the member state concerned, change the status of an overseas country or territory (OCT) to an outermost region (OMR) or vice versa.[131] This provision was included on a proposal by the Netherlands, which is investigating the future of the Netherlands Antilles and Aruba in the European Union as part of an institutional reform process that is currently taking place in the Netherlands Antilles.

Revision procedures

The Process for revision of the Treaties is divided into the ordinary revision procedure and simplified revision procedure. In the ordinary procedure the government of a Member State, the European Parliament or the Commission submits proposed amendments to the Council which submits them to the European Council. The national parliaments are also notified on the proposal. The European Council, after consulting the European Parliament and Commission, decides by simple majority whether to examine the amendments. If approved, the Presidency of the European Council will then convene a Convention composed of representatives of the national Parliaments, of the Heads of State or Government of the Member States, of the European Parliament and of the Commission. In the case of institutional changes in the monetary area the European Central Bank shall also be consulted. After examining the proposals the Convention will adopt by consensus a recommendation to a conference of representatives of the governments of the Member States convened by the President of the Council to determine by common accord the amendments to be made to the Treaties. Following this the amendments will go through the ratification process in each Member State. The European Council can decide by simple majority after consulting the Commission and with consent of the European Parliament to bypass the Convention process and proceed straight to the conference of representatives.

In the simplified procedure proposals for amendments to Part Three of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union, dealing with internal policy and action of the Union, can be submitted directly to the European Council. The European Council then decides by unanimity on amendments to the provisions after consulting the European Parliament and the Commission, and the European Central Bank in the case of institutional changes in the monetary area. The Treaties also provide for areas decided by unanimity to be changed to qualified majority after unanimous vote by the European Council after getting the consent of the European Parliament except areas with military implications or on defense. The European Council can also decide by unanimity to change areas decided by special legislative procedures to be decided by the ordinary legislative procedure after getting consent of the European Parliament.

Climate change

The Treaty of Lisbon adds explicit sentences stating that combating climate change and global warming are targets of the Union.

Mutual solidarity

Under the Treaty of Lisbon, Member States should assist if a member state is subject to a terrorist attack or the victim of a natural or man-made disaster[132] (but any joint military action is subject to the provisions of Article 31 of the consolidated Treaty of European Union, which recognises various national concerns). In addition, several provisions of the treaties have been amended to include solidarity in matters of energy supply and changes to the energy policy within the EU.

Defence

The treaty foresees that the European Security and Defence Policy will lead to a common defence agreement for the EU if and when the European Council (national leaders) resolves unanimously to do so and provided that all member states give their approval through their usual constitutional procedures.[133]

Opt-outs

- Further information: Opt-outs in the European Union

United Kingdom and Poland

The "Charter of Fundamental Rights of the European Union" by the European Court of Justice is not to apply fully to the United Kingdom and Poland, although it would still bind the EU institutions and apply to the field of EU law:

| “ | Article 1 1. The Charter does not extend the ability of the Court of Justice of the European Union, or any court or tribunal of Poland or of the United Kingdom, to find that the laws, regulations or administrative provisions, practices or action of Poland or of the United Kingdom are inconsistent with the fundamental rights, freedoms and principles that it reaffirms. |

” |

|

—Reform Treaty - Protocol (No 7)[134] |

||

Though the Civic Platform party in Poland had signalled during the 2007 parliamentary elections that it would not seek to opt-out from the Charter,[135] Prime Minister Tusk has since stated that Poland will not sign up to the Charter. Tusk declared that the deals negotiated by the previous Polish government will be honoured,[136] though suggested that Poland may eventually sign up to the Charter at a later date.[137]

Ireland and United Kingdom

Ireland and the United Kingdom have opted out from the change from unanimous decisions to qualified majority voting in the sector of police and judicial affairs; this decision will be reviewed in Ireland three years after the treaty enters into force (if the Treaty is ever approved by referendum in Ireland). Both states will be able to opt in to these voting issues on a case-by-case basis.

Member States can have opt-outs from some of these policy areas (e.g. UK opt-out from some legislation in the area of freedom, security and justice).

The Treaty will provide countries with the option to opt out of certain EU policies in the area of police and criminal law.[130] Provisions in the Treaty framework draft from the June 2007 summit stated that the division of power between Member States and the Union is a two-way process, implying that powers can be taken back from the union.

Compared to the Constitutional Treaty

Most of the institutional innovations that were agreed upon in the European Constitution, are kept in the Treaty of Lisbon. The most prominent difference is arguably that the Treaty of Lisbon amends existing EU treaties, rather than re-founding the EU by replacing old texts with a single document with the status of a constitution. Other differences include:

- The planned 'Union Minister for Foreign Affairs' has been renamed 'High Representative of the Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy'.

- EU symbols like the flag, the motto and the anthem, are not made legally binding in the Treaty of Lisbon. All of them are however already in use; e.g. the flag was adopted in the 1980s. Sixteen EU-countries have declared their allegiance to these symbols in the new treaty, although the annexed declaration is not legally binding.[138][139]

- In line with eliminating all 'state-like' terminology and symbols, new names for various types of EU legislation have been dropped, in particular the proposal to rename EU regulations and EU directives as EU 'laws'.[119][118][6][140]

- Three EU Member States have negotiated additional opt-outs from certain areas of policy, particularly the UK (see above).

- Due to Poland's pressure during the June Council in 2007, the new voting system will not enter into force before 2014.

- Combating climate-change is explicitly stated as an objective of EU institutions in the Treaty of Lisbon.

- The EU Constitution would have laid down as an objective of the EU the encouraging of "free and undistorted competition". Due to pressure from the French government, this phrase was not included in the Lisbon Treaty. Instead, the text relating to free and undistorted competition in Article 3 of the EC Treaty is kept and moved to Protocol 6 ("On the Internal Market and Competition"). There has been some debate over whether this will have an impact on EU Competition policy in future. Whilst French President Nicolas Sarkozy declared "We have obtained a major reorientation of the union's objectives",[141] EU commissioner Neelie Kroes has refuted such claims, stating "putting it in a Protocol on the internal market clarifies that one cannot exist without the other. They have moved the furniture round, but the house is still there. The Protocol is of equivalent status to the Treaty."[142]

See also

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Quoted from theTreaty Preamble

- ↑ Results of the Irish Referendum on the The Lisbon Treaty[1]

- ↑ "Constitutional Treaty: the "reflection period"". EurActiv (2007-06-01). Retrieved on 2007-06-26.

- ↑ "http://www.iue.it/RSCAS/e-texts/ACED2007_NewTreatyMemorandum-04_06.pdf" (PDF). Action Committee for European Democracy (2007-06-22). Retrieved on 2008-03-08.

- ↑ "[0712.2699] Square root voting in the Council of the European Union: Rounding effects and the Jagiellonian Compromise". Arxiv.org. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 6.2 6.3 6.4 "Presidency Conclusions Brussels European Council 21/22 June 2007" (PDF). Council of the European Union (23 June 2007). Retrieved on 2007-06-26.; Honor Mahony (21 June 2007). "Stakes high as EU tries to put 2005 referendums behind it". EU Observer. Retrieved on 2007-06-26.

- ↑ George Pascoe-Watson (22 June 2007). "EU can't mention the war", The Sun. Retrieved on 2007-06-26.

- ↑ Bruno Waterfield and Toby Helm (23 July 2007). "EU treaty must be re-written, warn MPs", The Daily Telegraph.

- ↑ 9.0 9.1 9.2 9.3 "Draft Reform Treaty – Projet de traité modificatif". Council of the European Union (24 July 2007). Retrieved on 2007-07-24.

- ↑ "Parliament to give green light for IGC". Euractiv.com (2007-07-09). Retrieved on 2007-07-09.

- ↑ Kubosova, Lucia (2007-07-20). "Poland indicates it is ready to compromise on EU voting rights". EU Observer. Retrieved on 2007-07-20.

- ↑ "EU leaders agree new treaty deal", BBC News Online (19 October 2007).

- ↑ Declaration on Article 222 of the Treaty on the Functioning of the European Union on the number of Advocates-General in the Court of Justice (pdf).

- ↑ AFP: Government wins first round in battle over EU treaty

- ↑ Article 6(2) of the Lisbon Treaty.

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 Article 6, paragraph 1 of the Treaty requires that instruments of ratification be deposited with the Government of Italy in order for the Treaty to enter into force. Each country deposits the instrument of ratification after its internal ratification process is finalized by all required state bodies (parliament and the head of state). Deposition details

- ↑ Press Office of the Parliament of Austria (2008-04-09). "Große Mehrheit für den Vertrag von Lissabon" (in German). Press release. Retrieved on 2008-04-10.

- ↑ PK0365 | Bundesrat gibt grünes Licht für EU-Reformvertrag (PK0365/24.04.2008)

- ↑ (2008-04-28). "Austrian president formally ratifies EU treaty". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-06-23.

- ↑ "Belgian senate approves EU's Lisbon treaty". EUbusiness.com (2008-03-06).

- ↑ "Kamer keurt Verdrag van Lissabon goed" (in Dutch) p. 1. De Morgen. Retrieved on 2008-04-11.

- ↑ "Fiche du dossier" (in French). Sénat de Belgique. Retrieved on 2008-07-10.

- ↑ "Parlement wallon CRA 14 mai 2008" (PDF) (in French) p. 49. Parlement wallon. Retrieved on 2008-05-19.

- ↑ "Parlement wallon CRA 14 mai 2008" (PDF) (in French) p. 50. Parlement wallon. Retrieved on 2008-05-19.

- ↑ "PDG stimmt Vertrag von Lissabon zu" (in German) p. 1. BRF. Retrieved on 2008-05-20.

- ↑ "Compte rendu intégral de la séance du mardi 20 mai 2008 (après-midi)" (in French) p.32. Parlement de la Communauté française. Retrieved on 2008-05-21.

- ↑ "Compte rendu intégral de la séance du vendredi 27 juin 2008 (après-midi)" (PDF) (in French). Retrieved on 2008-07-03.

- ↑ French language group: 56 yes, 5 no; Dutch language group: 10 yes, 5 no; "CRI IV" (PDF) (in French and Dutch). Retrieved on 2008-07-03.

- ↑ 29.0 29.1 "Plenaire Vergadering van 10-07-2008" (in Dutch). Retrieved on 2008-07-10.

- ↑ "Compte rendu: séance plénière du vendredi 11 juillet 2008 (version provisoire du 17.07.2008)" (PDF) (in French) pp. 45-46. Parlement francophone bruxellois. Retrieved on 2008-07-17.

- ↑ Press release of the National Assembly of Bulgaria

- ↑ AFP: "Cyprus ratifies EU treaty". Retrieved on 3 July 2008.

- ↑ Press and information office. Retrieved on 10 October 2008.

- ↑ "Czech lower house to meet on Dec 9 over Lisbon treaty". Czech Press Agency (2008-12-01). Retrieved on 2008-12-01.

- ↑ Czech Radio - Český rozhlas

- ↑ "Danish parliament ratifies EU's Lisbon Treaty" (2008-04-24). Retrieved on 2008-04-24.

- ↑ "Lov om ændring af lov om Danmarks tiltrædelse af De Europæiske Fællesskaber og Den Europæiske Union", retsinformation.dk (2008-04-30). Retrieved on 2008-07-12.

- ↑ Parliament of Estonia

- ↑ (2008-06-19). "Factbox: Lisbon's fate around the EU". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-07-01.

- ↑ Parliament of Finland

- ↑ Finland ratifies EU's Lisbon Treaty

- ↑ Assemblée nationale - Analyse du scrutin n°83 - Séance du : 07/02/2008

- ↑ Sénat - Compte rendu analytique officiel du 7 février 2008

- ↑ Official Journal of the French Republic, 14 February 2008, page 2712

- ↑ "Deutscher Bundestag: Fehlermeldung". Bundestag.de. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ Deutscher Bundestag: Ergebnisse der namentlichen Abstimmungen

- ↑ Honor Mahony. "EUobserver.com". Euobserver.com. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ Report of "der Spiegel" about the Bundesrat vote

- ↑ "Germany a Step Closer to Ratifying Lisbon Treaty" (8 October 2008). Retrieved on 2008-10-12.

- ↑ "Greek Parliament ratifies Lisbon Treaty", Athens News Agency (2008-09-14). Retrieved on 2008-07-11.

- ↑ "Híradó". Hirado.hu. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "Az Európai Unióról szóló szerződés és az Európai Közösséget létrehozó szerződés módosításáról szóló lisszaboni szerződés kihirdetéséről". Hungarian National Assembly. Retrieved on 2008-09-29.

- ↑ 53.0 53.1 53.2 Twenty-eighth Amendment of the Constitution of Ireland Bill, 2008

- ↑ "Italy's Senate approves EU treaty". eubusiness.com (2008-07-23). Retrieved on 2008-07-25.

- ↑ "Italian MPs give thumbs-up to EU's Lisbon treaty". FOCUS Information Agency. Retrieved on 2008-07-30.

- ↑ "Atti firmati; Settimana 28 Luglio - 03 Agosto 2008", Quirinale (2008-08-05).

- ↑ "Latvia, Lithuania ratify Lisbon treaty", The Irish Times (2008-05-08).

- ↑ "Lithuania ratifies Lisbon treaty", RTE (2008-05-08).

- ↑ (2008-05-14). "Lisbon Treaty is another step forward on the European road, says the President". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-07-11.

- ↑ EUbusiness.com - Luxembourg is 15th EU state to ratify treaty in parliament

- ↑ "Approbation du Traité de Lisbonne du 13 décembre 2007". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-08-14.

- ↑ "Javno - World". Javno.com. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ It follows from the official parliamentary report [2] that following the vote, the chairwoman has stated (translation) : "I notice that the Members of the parliamentary groups of PvdA, GroenLinks, D66, VVD, ChristenUnie and CDA who are present have voted in favour and that those of the other parliamentary groups have voted against; the Bill has therefore been adopted."

- ↑ NU.nl

- ↑ Staatsblad 2008, number 301 of 24th of July 2008: [3]

- ↑ Elitsa Vucheva. "EUobserver.com". Euobserver.com. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "Polish parliament ratifies EU treaty", EUobserver.com (2008-04-02). Retrieved on 2008-07-29.

- ↑ (in Polish) http://isip.sejm.gov.pl/servlet/Search?todo=file&id=WDU20080620388&type=2&name=D20080388.pdf

- ↑ "Portuguese parliament ratifies EU's Lisbon treaty". EUbusiness (2008-04-23). Retrieved on 2008-04-23.

- ↑ {{{author}}}, Ratification of the Treaty of Lisbon, [[{{{publisher}}}]], 2008-07-04.

- ↑ Pursuant to the Constitution, the ratification occurred in a joint session of both houses.

- ↑ Romanian parliament ratifies Lisbon Treaty

- ↑ "Proiect de Lege pentru ratificarea Tratatului de la Lisabona de modificare a Tratatului privind Uniunea Europeană şi a Tratatului de instituire a Comunităţii Europene, semnat la Lisabona la 13 decembrie 2007". Camera Deputaţilor (2008-02-12). Retrieved on 2008-07-07.

- ↑ Lucia Kubosova. "EUobserver.com". Euobserver.com. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ (Slovak) The treaty of Lisbon was ratified thanks to opposition party

- ↑ (2008-05-12). "Slovak President ratifies EU's reforming Lisbon Treaty". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-06-23.

- ↑ Slovenia ratifies Lisbon treaty : Europe World

- ↑ "AFTER IRISH ‘NO’: Spanish Congress ratifies Lisbon Treaty", Newstin (2008-06-26). Retrieved on 2008-06-27.

- ↑ "UE.- El Senado celebrará un pleno extraordinario el 15 de julio para completar la ratificación del Tratado de Lisboa".

- ↑ {{{author}}}, Ley Orgánica 1/2008, de 30 de julio, [[{{{publisher}}}]], 2008-07-31.

- ↑ "Ja till Lissabonfördraget" (in swedish). SVT (2008-11-20). Retrieved on 2008-11-20.

- ↑ Ja till Lissabonfördraget, TT via Aftonbladet, November 20, 2008.

- ↑ House of Commons voting does not permit Members to abstain. 81 Members were able to vote but did not do so.

- ↑ EU treaty bill clears the Commons

- ↑ "Bills and Legislation - European Union (Amendment) Bill". Services.parliament.uk. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ Lords Hansard

- ↑ Written Ministerial Statement by Jim Murphy MP confirming the UK's Ratification

- ↑ The Åland Islands are an autonomous province of Finland. It is part of the European Union, but is subject of certain exemptions. Åland Islands Parliament ratification is not necessary for the Treaty to enter into force, but is needed for its provisions to apply on the territory of the Åland Islands.

- ↑ "Finnish islands cause headache for EU treaty approval". Press release. Retrieved on 2008-08-13.

- ↑ Gibraltar is a British overseas territory. It is part of European Union, but is subject of certain exemptions. Gibraltar Parliament ratification is not necessary for the Treaty to enter into force, but changes in the legislation are needed for its provisions to apply on the territory of Gibraltar.

- ↑ The European Parliament's vote is advisory only and has no legal basis. I Lisbon comes into force the Parliament's consent will be required for future treaty changes.

- ↑ European Parliament approve EU's Lisbon Treaty

- ↑ Justin Stares (14 June 2008). "EU referendum: Czech president says Lisbon Treaty project is over", The Telegraph. Retrieved on 2008-12-02.

- ↑ "Czech president digs his heels in against EU Treaty". Euractiv.com (25 July 2008). Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "Czech president might sign Lisbon treaty only after Irish "yes"". Czech Press Agency (2008-11-24). Retrieved on 2008-11-24.

- ↑ "The thorny question of the EU treaty and the Czech Republic". EUobserver (2008-08-05). Retrieved on 2008-10-30.

- ↑ "Czechs not to ratify Lisbon treaty in 2008 - PM Topolanek". Czech Press Agency (2008-11-04). Retrieved on 2008-11-04.

- ↑ Flera ändringar på gång i självstyrelselagen, Nya Åland (Swedish)

- ↑ Composition of the European Parliament after European elections in June 2009

- ↑ Relative influence of voters from different EU countries

- ↑ "FG calls on public to back Lisbon Treaty", RTÉ News (22 January 2008).

- ↑ "Ireland rejects EU reform treaty", BBC News (13 June 2008).

- ↑ "Results received at the Central Count Centre for the Referendum on The Lisbon Treaty from Referendum Ireland". Retrieved on 2008-06-13.

- ↑ "FL245_Irish referendum_preliminary findingsfinal mr_changes in intro 20.06.08 final.doc" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "Microsoft Word - Post Lisbon Treaty Referendum Research Findings.doc" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "Ireland mulls autumn 2009 Lisbon revote", EUobserver (2008-07-30). Retrieved on 2008-09-11.

- ↑ See John O'Brennan, 'Ireland and the Lisbon Treaty: Quo Vadis? CEPS Policy Brief No.175, Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies, 23 October 2008, http://shop.ceps.eu/BookDetail.php?item_id=1741

- ↑ Irish Times, 12 November 2008, p.7.

- ↑ (German) Köhler stoppt EU-Vertrag, Sueddeutsche Zeitung, June 30, 2008.

- ↑ DW staff (sp). "German President Suspends Ratification of EU Lisbon Treaty | Germany | Deutsche Welle | 30.06.2008". Dw-world.de. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "the tap: German Lisbon Ratification Also Uncertain". The-tap.blogspot.com (June 14, 2008). Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "Germany a Step Closer to Ratifying Lisbon Treaty" (8 October 2008). Retrieved on 2008-10-12.

- ↑ (Polish) http://isip.sejm.gov.pl/servlet/Search?todo=file&id=WDU20080620388&type=2&name=D20080388.pdf

- ↑ "The Constitution of the Republic of Poland". Sejm.gov.pl. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "Prezydent RP - Dokument docelowy kroniki Strony głównej". Prezydent.pl. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ Philippa Runner. "EUobserver". Euobserver.com. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "untitled" (PDF). Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ 118.0 118.1 Mark Tran (21 June 2007). "How the German EU proposals differ from the constitution". The Guardian. Retrieved on 2007-06-26.

- ↑ 119.0 119.1 "LinksDossier: EU in search of a new Treaty". EurActiv.com (26 April 2007). Retrieved on 2007-06-26.

- ↑ Amended Article 234 EC, to become Article 266 TEFU

- ↑ Amended Article 240a, to become Article 274 TEFU

- ↑ Amended Article 240b, to become Article 275 TEFU

- ↑ Honor Mahony (23 June 2007). "EU leaders scrape treaty deal at 11th hour". EU Observer. Retrieved on 2007-06-26.

- ↑ Mardell, Mark. Tony Blair and the race for the presidency, BBC News, 6 February 2008. Accessed 18 June 2008.

- ↑ Eur-Lex. "Consolidated EU Treaties" (PDF). Retrieved on 2007-06-27.

- ↑ Europa website. "SCADPlus: The Institutions of the Union". Retrieved on 2007-06-27.

- ↑ "Sarkozy suggests Blair as first president of the EU". Retrieved on 2008-03-28.

- ↑ "Blair for president...". Retrieved on 2008-03-28.

- ↑ Richard Lamming (28 June 2007). "A treaty for foreign policy" (PDF). EU Observer. Retrieved on 2007-08-19.

- ↑ 130.0 130.1 130.2 Honor Mahony (20 June 2007). "EU treaty blueprint sets stage for bitter negotiations". EU Observer. Retrieved on 2007-06-26.

- ↑ The provision reads:

Article 311 shall be repealed. A new Article 311a shall be inserted, with the wording of Article 299(2), first subparagraph, and Article 299(3) to (6); the text shall be amended as follows:

[...]

(e) the following new paragraph shall be added at the end of the Article:

"6. The European Council may, on the initiative of the Member State concerned, adopt a decision amending the status, with regard to the Union, of a Danish, French or Netherlands country or territory referred to in paragraphs 1 and 2. The European Council shall act unanimously after consulting the Commission."—Treaty of Lisbon Article 2, point 293 - ↑ Article 222 of consolidated "Functioning of the European Union"

- ↑ Preamble and Article 42 of the (consolidated) Treaty of European Union

- ↑ IGC 2007 (October 2007). "Protocol (No 7) - On the Application of the Charter of Fundamental Rights to Poland and to the United Kingdom" (PDF). Projet de traité modifiant le traité sur l'Union européenne et le traité instituant la Communauté européenne - Protocoles. European Union.

- ↑ Staff writer (2007-10-22). "Poland's new government will adopt EU rights charter: official", EUbusiness. Retrieved on 2007-10-22.

- ↑ Staff writer (2007-11-23). "No EU rights charter for Poland", BBC News. Retrieved on 2007-11-23.

- ↑ "Russia poll vexes EU and Poland", BBC News Online (4 December 2007).

- ↑ "Germany seeks to enshrine EU flag", The Daily Telegraph (2007-12-11). Retrieved on 2007-12-11.

- ↑ "Final Act" (PDF). Council of the European Union (2007-12-03). Retrieved on 2007-12-11.

- ↑ Beunderman, Mark (2007-07-11). "MEPs defy Member States on EU symbols". EU Observer. Retrieved on 2007-07-12.

- ↑ "France's hyperactive president | The Sarko show | Economist.com". Economist.com. Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

- ↑ "EurActiv.com - Brussels plays down EU Treaty competition fears | EU - European Information on Competition". Euractiv.com (Published: Wednesday 27 June 2007). Retrieved on 2008-09-16.

External links

Official websites

- Official website – Europa

- Treaty of Lisbon (the amendments)

- Consolidated treaties (the result of the amendments)

- Ceremony of the signature of the Treaty of Lisbon (video)

- Treaty of Lisbon – European Commission Representation to Ireland

- Irish Government information site for the Reform Treaty – Irish Department of Foreign Affairs

- 10 Myths about the Reform Treaty – British Foreign and Commonwealth Office

Media overviews

- Q&A: The Lisbon Treaty – BBC News

- The 'Treaty of Lisbon' – EurActiv

- The EU following the Lisbon Treaty – Eur-charts visualization

- The new EU reform treaty – Federal Union

- Q&A: the EU reform treaty – The Times

- Ratification Monitor – Bertelsmann Foundation

|

|||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||