Legal history

Legal history or the history of law is the study of how law has evolved and why it changed. Legal history is closely connected to the development of civilizations and is set in the wider context of social history. Among certain jurists and historians of legal process it has been seen as the recording of the evolution of laws and the technical explanation of how these laws have evolved with the view of better understanding the origins of various legal concepts, some consider it a branch of intellectual history. Twentieth century historians have viewed legal history in a more contextualized manner more in line with the thinking of social historians. They have looked at legal institutions as complex systems of rules, players and symbols and have seen these elements interact with society to change, adapt, resist or promote certain aspects of civil society. Such legal historians have tended to analyze case histories from the parameters of social science inquiry, using statistical methods, analyzing class distinctions among litigants, petitioners and other players in various legal processes. By analyzing case outcomes, transaction costs, number of settled cases they have begun an analysis of legal institutions, practices, procedures and briefs that give us a more complex picture of law and society than the study of jurisprudence, case law and civil codes can achieve.

Contents |

Ancient World

- See also: Urukagina, Hittite laws, and Ostracism

Ancient Egyptian law, dating as far back as 3000 BCE, had a civil code that was probably broken into twelve books. It was based on the concept of Ma'at, characterised by tradition, rhetorical speech, social equality and impartiality.[1] By the 22nd century BCE, Ur-Nammu, an ancient Sumerian ruler, formulated the first law code, consisting of casuistic statements ("if... then..."). Around 1760 BCE, King Hammurabi further developed Babylonian law, by codifying and inscribing it in stone. Hammurabi placed several copies of his law code throughout the kingdom of Babylon as stelae, for the entire public to see; this became known as the Codex Hammurabi. The most intact copy of these stelae was discovered in the 19th century by British Assyriologists, and has since been fully transliterated and translated into various languages, including English, German, and French. The Torah from the Old Testament is probably the oldest body of law still relevant for modern legal systems, dating back to 1280 BCE. It takes the form of moral imperatives, like the Ten Commandments and the Noahide Laws, as recommendations for a good society. Ancient Athens, the small Greek city-state, was the first society based on broad inclusion of the citizenry, excluding women and the slave class. Athens had no legal science, and Ancient Greek has no word for "law" as an abstract concept.[2] Yet Ancient Greek law contained major constitutional innovations in the development of democracy.[3]

Southern Asia

Ancient India and China represent distinct traditions of law, and had historically independent schools of legal theory and practice. The Arthashastra, dating from the 400 BCE, and the Manusmriti from 100 CE were influential treatises in India, texts that were considered authoritative legal guidance.[4] Manu's central philosophy was tolerance and pluralism, and was cited across South East Asia.[5] But this Hindu tradition, along with Islamic law, was supplanted by the common law when India became part of the British Empire.[6] Malaysia, Brunei, Singapore and Hong Kong also adopted the common law.

Eastern Asia

The eastern Asia legal tradition reflects a unique blend of secular and religious influences.[7] Japan was the first country to begin modernizing its legal system along western lines, by importing bits of the French, but mostly the German Civil Code.[8] This partly reflected Germany's status as a rising power in the late nineteenth century. Similarly, traditional Chinese law gave way to westernization towards the final years of the Ch'ing dynasty in the form of six private law codes based mainly on the Japanese model of German law.[9] Today Taiwanese law retains the closest affinity to the codifications from that period, because of the split between Chiang Kai-shek's nationalists, who fled there, and Mao Zedong's communists who won control of the mainland in 1949. The current legal infrastructure in the People's Republic of China was heavily influenced by soviet Socialist law, which essentially inflates administrative law at the expense of private law rights.[10] Today, however, because of rapid industrialization China has been reforming, at least in terms of economic (if not social and political) rights. A new contract code in 1999 represented a turn away from administrative domination.[11] Furthermore, after negotiations lasting fifteen years, in 2001 China joined the World Trade Organization.[12]

Islamic law

- See also: Fiqh, Islamic ethics, Early reforms under Islam, and Islamic Jurisprudence: An International Perspective

One of the major legal systems developed during the Middle Ages was Islamic law and jurisprudence, now the third most common legal system after the civil law and common law systems.[13] The methodology of legal precedent and reasoning by analogy (Qiyas) used in early Islamic law was similar to that of the later common law system.[14] According to Justice Gamal Moursi Badr, Islamic law is like common law in that it "is not a written law" based entirely on the Qur'an but that the "provisions of Islamic law are to be sought first and foremost in the teachings of the authoritative jurists" (Ulema), hence Islamic law may "be called a lawyer's law if common law is a judge's law."[15] This was particularly the case for the Maliki school of Islamic law active in North Africa, Islamic Spain and the Emirate of Sicily.[16]

A number of important legal institutions were developed by Islamic jurists during the classical period of Islamic law and jurisprudence, known as the Islamic Golden Age, dated from the 7th to 13th centuries. One such institution was the Hawala, an early informal value transfer system, which is mentioned in texts of Islamic jurisprudence as early as the 8th century. Hawala itself later influenced the development of the Aval in French civil law and the Avallo in Italian law.[15] The "European commenda" limited partnerships (Islamic Qirad) used in civil law as well as the civil law conception of res judicata may also have origins in Islamic law.[16]

Several fundamental common law instutitions may have been adapted from similar legal institutions in Islamic law and jurisprudence, and introduced to England after the Norman conquest of England by the Normans, who conquered and inherited the Islamic legal administration of the Emirate of Sicily, and also by Crusaders during the Crusades. In particular, the "royal English contract protected by the action of debt is identified with the Islamic Aqd, the English assize of novel disseisin is identified with the Islamic Istihqaq, and the English jury is identified with the Islamic Lafif" in Maliki law.[16] The English trust and agency institutions in common law were also most likely adapted from the Islamic Waqf and Hawala institutions respectively during the Crusades.[17][15]

Other English legal institutions such as "the scholastic method, the license to teach," the "law schools known as Inns of Court in England and Madrasas in Islam" and the "European commenda" (Islamic Qirad) may have also originated from Islamic law.[16] The methodology of legal precedent and reasoning by analogy (Qiyas) are also similar in both the Islamic and common law systems.[18] These similarities and influences have led some scholars to suggest that Islamic law may have laid the foundations for "the common law as an integrated whole".[16]

European laws

Roman Empire

Roman law was heavily influenced by Greek teachings.[19] It forms the bridge to the modern legal world, over the centuries between the rise and decline of the Roman Empire.[20] Roman law, in the days of the Roman republic and Empire, was heavily procedural and there was no professional legal class.[21] Instead a lay person, iudex, was chosen to adjudicate. Precedents were not reported, so any case law that developed was disguised and almost unrecognised.[22] Each case was to be decided afresh from the laws of the state, which mirrors the (theoretical) unimportance of judges' decisions for future cases in civil law systems today. During the 6th century AD in the Eastern Roman Empire, the Emperor Justinian codified and consolidated the laws that had existed in Rome so that what remained was one twentieth of the mass of legal texts from before.[23] This became known as the Corpus Juris Civilis. As one legal historian wrote, "Justinian consciously looked back to the golden age of Roman law and aimed to restore it to the peak it had reached three centuries before."[24]

Middle Ages

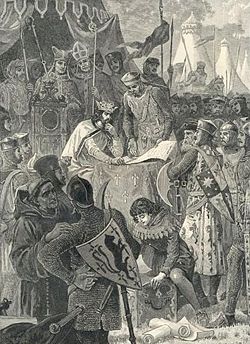

- See also: Germanic tribal laws, Visigothic Code, Dōm, Blutgericht, Magna Carta, and Schwabenspiegel

Roman law was lost through the Dark Ages, but in the eleventh century AD scholars in the University of Bologna rediscovered the texts and were the first to use them to interpret their own laws.[25] Mediæval European legal scholars began researching the Roman law and they began using its concepts[26] and prepared the way for the partial resurrection of Roman law as the modern civil law in a large part of the world.[27] After the Norman conquest of England which introduced Norman and Islamic legal concepts into mediæval England, the English King's powerful judges developed a body of precedent which became the common law.[16] But also, a Europe wide lex mercatoria was formed, so that merchants could trade using familiar standards, rather than the many splintered types of local law. A precursor to modern commercial law, the lex mercatoria emphasised the freedom of contract and alienability of property.[28]

Modern European law

The two main traditions of modern European law are the codified legal systems of most of continental Europe, and the English tradition based on case law.

As nationalism grew in the 18th and 19th centuries, lex mercatoria was incorporated into countries' local law under new civil codes. Of these, the French Napoleonic Code and the German Bürgerliches Gesetzbuch became the most influential. As opposed to English common law, which consists of massive tomes of case law, codes in small books are easy to export and for judges to apply. However, today there are signs that civil and common law are converging. European Union law is codified in treaties, but develops through the precedent laid down by the European Court of Justice.

United States

The United States legal system developed primarily out of the English common law system (with the exception of the state of Louisiana, which continued to follow the French civilian system after being admitted to statehood). Some concepts which originate in Spanish law, such as the prior appropriation doctrine and community property, still persist in some U.S. states, particularly those which were part of the Mexican Cession in 1848.

Under the doctrine of federalism, each state has its own separate court system, and the ability to legislate within areas not reserved to the federal government.

Footnotes

- ↑ Théodoridés "law". Encyclopedia of the Archaeology of Ancient Egypt.

* VerSteeg, Law in ancient Egypt - ↑ Kelly, A Short History of Western Legal Theory, 5-6

- ↑ Ober, The Nature of Athenian Democracy, 121

- ↑ Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World, 255

- ↑ Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World, 276

- ↑ Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World, 273

- ↑ Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World, 287

- ↑ Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World, 304

- ↑ Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World, 305

- ↑ Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World, 307

- ↑ Glenn, Legal Traditions of the World, 309

- ↑ Farah, Five Years of China WTO Membership, 263-304

- ↑ Badr, Gamal Moursi (Spring, 1978), "Islamic Law: Its Relation to Other Legal Systems", The American Journal of Comparative Law 26 (2 [Proceedings of an International Conference on Comparative Law, Salt Lake City, Utah, February 24-25, 1977]): 187–198, doi:

- ↑ El-Gamal, Mahmoud A. (2006), Islamic Finance: Law, Economics, and Practice, Cambridge University Press, p. 16, ISBN 0521864143

- ↑ 15.0 15.1 15.2 Badr, Gamal Moursi (Spring, 1978), "Islamic Law: Its Relation to Other Legal Systems", The American Journal of Comparative Law 26 (2 [Proceedings of an International Conference on Comparative Law, Salt Lake City, Utah, February 24-25, 1977]): 187–198 [196–8], doi:

- ↑ 16.0 16.1 16.2 16.3 16.4 16.5 Makdisi, John A. (June 1999), "The Islamic Origins of the Common Law", North Carolina Law Review 77 (5): 1635–1739

- ↑ Gaudiosi, Monica M. (April 1988), "The Influence of the Islamic Law of Waqf on the Development of the Trust in England: The Case of Merton College", University of Pennsylvania Law Review 136 (4): 1231-1261

- ↑ El-Gamal, Mahmoud A. (2006), Islamic Finance: Law, Economics, and Practice, Cambridge University Press, p. 16, ISBN 0521864143

- ↑ Kelly, A Short History of Western Legal Theory, 39

- ↑ As a legal system, Roman law has affected the development of law in most of Western civilization as well as in parts of the Eastern world. It also forms the basis for the law codes of most countries of continental Europe ( "Roman law". Encyclopaedia Britannica.).

- ↑ Gordley-von Mehren, Comparative Study of Private Law, 18

- ↑ Gordley-von Mehren, Comparative Study of Private Law, 21

- ↑ Stein, Roman Law in European History, 32

- ↑ Stein, Roman Law in European History, 35

- ↑ Stein, Roman Law in European History, 43

- ↑ Roman and Secular Law in the Middle Ages

- ↑ Roman law

- ↑ Sealey-Hooley, Commercial Law, 14

References

- Farah, Paolo (August 2006). "Five Years of China WTO Membership. EU and US Perspectives about China's Compliance with Transparency Commitments and the Transitional Review Mechanism". Legal Issues of Economic Integration 33 (3): 263–304. http://papers.ssrn.com/sol3/papers.cfm?abstract_id=916768.

- Barretto, Vicente (2006). Dicionário de Filosofia do Direito. Unisinos Editora. ISBN 85-7431-266-5.

- Glenn, H. Patrick (2000). Legal Traditions of the World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198765754.

- Sadakat Kadri, The Trial: A History from Socrates to O.J. Simpson, HarperCollins 2005. ISBN 0-00-711121-5

- Kelly, J.M. (1992). A Short History of Western Legal Theory. Oxford University Press. ISBN 0198762445.

- Gordley, James R.; von Mehren, Arthur Taylor (2006). An Introduction to the Comparative Study of Private Law. ISBN 9-780-52168-185-8.

- Sealy, L.S.; Hooley, R.J.A. (2003). Commercial Law. LexisNexis Butterworths.

- Stein, Peter (1999). Roman Law in European History. Cambridge University Press. pp. 32. ISBN 0-521-64372-4.

- Kempin, Jr., Frederick G. (1963). Legal History: Law and Social Change. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

See also

- Association of Young Legal Historians (AYLH)

- Constitution of the Roman Republic

External links

- The Legal History Project (Resources and interviews)

- Some legal history materials

- The Schoyen Collection

- The Roman Law Library by Yves Lassard and Alexandr Koptev.

- Law & Justice in Australia - online collection from the State Library of NSW

- Legal History: Evolution of Law

- Centre for Legal History - Edinburgh Law School

- Collection of Historical Statutory Material - Cornell Law Library

- Historical Laws of Hong Kong Online - University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives

- Basic Law Drafting History Online -University of Hong Kong Libraries, Digital Initiatives

- Alan Watson Foundation- A Group of Scholars Dedicated to the Promotion of Legal History and Comparative Law

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||