Lassen Peak

| Lassen Peak | |

|---|---|

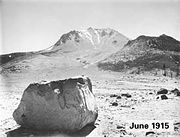

Lassen Peak and Devastated Area from Cinder Cone |

|

|

Lassen Peak

|

|

| Elevation | 10,462 feet (3,189 m) [1][2] |

| Location | California, USA |

| Range | Cascade Range |

| Prominence | 5,229 feet (1,594 m) [2] |

| Parent peak | Mount Whitney [2] |

| Coordinates | |

| Topo map | USGS Lassen Peak |

| Type | Lava dome |

| Volcanic arc/belt | Cascade Volcanic Arc |

| Age of rock | < 27,000 years |

| Last eruption | 1917 |

| Easiest route | hike |

Lassen Peak[3] (also known as Mount Lassen) is the southernmost active volcano in the Cascade Range. It is part of the Cascade Volcanic Arc which is an arc that stretches from northern California to southwestern British Columbia. Located in the Shasta Cascade region of Northern California, Lassen rises 2,000 feet (610 m) above the surrounding terrain and has a volume of half a cubic mile, making it one of the largest lava domes on Earth.[4] It was created on the destroyed northeastern flank of now gone Mount Tehama, a stratovolcano that was at least a thousand feet (300 m) higher than Lassen.

Lassen Peak has the distinction of being the only volcano in the Cascades other than Mount St. Helens to erupt during the 20th century. On May 22, 1915, an explosive eruption at Lassen Peak devastated nearby areas and rained volcanic ash as far away as 200 miles (320 km) to the east.[4] This explosion was the most powerful in a 1914–17 series of eruptions that were the last to occur in the Cascades before the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens in Washington. Lassen Volcanic National Park was created in Shasta County, California to preserve the devastated area and nearby volcanic wonders.

Unlike most lava domes, Lassen is topped by craters. In fact, a series of these craters exist around Lassen's summit, although two of these are now covered by solidified lava and sulfur deposits. Lassen is the largest of a group of more than 30 volcanic domes that have erupted over the past 300,000 years in the Lassen Volcanic Center.

Contents |

Climate

Lassen has the highest known snowfall amounts for California. With an average annual snowfall of 660 inches (16.76 m) , and some years receiving over 1,000 inches (25.4 m) of snow at its base of 8,250 feet (2,515 m) at Lake Helen. Mt. Lassen gets more precipitation (rain, hail, melted snow) anywhere in the Cascades south of the Three Sisters volcanoes.[5] This heavy snowfall allows Lassen to retain 14 permanent patches of snow despite Lassen's modest elevation.[6] Lightning has been known to frequently strike the summit of the volcano during summer thunderstorms.

Geology

- Further information: Lassen Volcanic National Park#Geology and Geology of the Lassen volcanic area

Lassen is the southernmost in the chain of 18 large volcanic peaks that run from southwestern British Columbia to northern California. The peaks formed in the past 35 million years as the Juan De Fuca plate and the tiny Gorda plate to its south have been pulled under the overriding North American plate. As the oceanic crust in the Juan de Fuca plate melts under the pressure, it creates pools of lava that drive up the Cascade Range and power periodic eruptions in its volcanic peaks.

Roughly 27,000 years ago,[4] Lassen started to form as a mound-shaped dacite lava dome pushed its way through Tehama's destroyed north-eastern flank. As the lava dome pushed its way up, it shattered overlaying rock, which formed a blanket of angular talus around the emerging steep-sided volcano (it looked much like the nearby 1,100-year-old Chaos Crags). Lassen rose and reached its present height in a relatively short time, probably in as little as a few years.

From 25,000 to 18,000 years ago, during the last glacial period of the current ice age, Lassen’s shape was significantly altered by glacial erosion. For example, the bowl-shaped depression on the volcano’s northeastern flank, called a cirque, was eroded by a glacier that extended out 7 miles (11 km) from the dome.[4]

Lassen's most recent eruptive period started in 1914 and lasted for seven years (see below). The most powerful of these eruptions was a 1915 episode that sent ash and steam in a ten-kilometer-tall mushroom cloud, making it the largest recent eruption in the contiguous 48 U.S. states until the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. The region remains geologically active, with mud pots, active fumaroles, and boiling water features, several of which are getting hotter. The area around Mount Lassen and nearby Mount Shasta are considered the most likely volcanoes in the Cascade Range to shift from dormancy to active eruptions.[7]

Human history

Before the arrival of white settlers, the areas surrounding Lassen Peak, especially in the east and south, were the traditional home of the (Northeastern) Maidu.

Lassen Peak was named in honor of Danish blacksmith Peter Lassen, who guided immigrants past the peak to Sacramento Valley in the 1830s. Lassen's trail, however, never found general long-term use because it was considered unsafe. Nobles Emigrant Trail, named after William Nobles, which linked Applegate Trail in Nevada to Northern Sacramento Valley, replaced it.

In 1864 Helen Tanner Brodt became the first woman to reach the summit of Lassen Peak. A tarn (lake in a cirque basin) on Lassen was named Lake Helen in her honor.

Starting in 1914 and ending in 1921 Lassen came alive with a series of phreatic eruptions (steam explosions), dacite lava flows, and lahars (volcanic mud flows). There were 200 to 400 volcanic eruptions during this period of activity. First-hand accounts of the time record at least one fatality, in 1915.

Early 20th century eruptions

Initial rumblings (May 1914 to May 1915)

On May 30, 1914, Lassen became active again after 27,000 years dormancy when it was shaken by a steam explosion. Such steam blasts occur when molten rock (magma) rises toward the surface of a volcano and heats shallow ground water. The hot water rises under pressure through cracks and, on nearing the surface, vaporizes and vents explosively. By mid-May 1915, more than 180 steam explosions had blasted out a 1,000 ft (300 m) wide crater near the summit of Lassen Peak.[4]

Then the character of the eruption changed dramatically. On the evening of May 14, 1915, incandescent blocks of lava could be seen bouncing down the flanks of Lassen from as far away as the town of Manton, California 20 miles (30 km) to the west.[4] By the next morning, a growing dome of dacite lava (lava containing 63 to 68% silica) had filled the volcano’s crater.

Events of May 19–20, 1915

Late on the evening of May 19, a large steam explosion fragmented the dacite dome, creating a new crater at the summit of Lassen Peak. No new magma was ejected in this explosion, but glowing blocks of hot lava from the dome fell on the summit and snow-covered upper flanks of Mount Lassen. These falling blocks launched a half mile (800 m) wide avalanche of snow and volcanic rock that roared 4 mi (6 km) down the volcano’s steep northeast flank and over a low ridge at Emigrant Pass into Hat Creek.[4]

As the hot lava blocks broke into smaller fragments, the snow melted, generating a mudflow of volcanic materials, called a lahar. The bulk of this lahar was deflected northwestward at Emigrant Pass and flowed 7 miles (11 km) down Lost Creek.[4] Even after coming to rest, both the avalanche and lahar released huge volumes of water, flooding the lower Hat Creek Valley during the early morning hours of May 20. The lahar and flood destroyed six mostly not-yet-occupied summer ranch houses. Fortunately, the few people in these houses escaped with only minor injuries.

Also during the night of May 19–20, dacite lava somewhat more fluid than that erupted on the night of May 14–15 welled up into and filled the new crater at Lassen’s summit, spilled over low spots on its rim, and flowed 1,000 feet (300 m) down the steep west and northeast flanks of the volcano.[4]

Climactic eruption of May 22, 1915

Then at 4:30 p.m. on May 22, after two quiet days, Lassen exploded in a powerful eruption (referred to as "the Great Explosion") that blasted volcanic ash, rock fragments and pumice high into the air. This created the larger and deeper of the two craters seen near the summit of the volcano today. A huge column of volcanic ash and gas rose more than 30,000 feet (9,000 m) into the air and was visible from as far away as Eureka, California 150 miles (241 km) to the west.[4]

Pumice falling onto the northeastern slope of Lassen Peak generated a high-speed avalanche of hot ash, pumice, rock fragments, and gas, called a pyroclastic flow, that swept down the side of the volcano, devastating a 3 square miles (8 km2) area.[4] The pyroclastic flow rapidly incorporated and melted snow in its path. The water from the melted snow transformed the flow into a highly fluid lahar that followed the path of the May 19–20 lahar and rushed nearly 10 miles (16 km) down Lost Creek to Old Station. This new lahar released a large volume of water that flooded lower Hat Creek Valley a second time.

The powerful climactic eruption of May 22 also swept away the northeast lobe of the lava flow extruded two days earlier. The eruption produced smaller mudflows on all flanks of Lassen Peak, deposited a layer of volcanic ash and pumice traceable for 25 miles (40 km) to the northeast, and rained fine ash at least as far away as Winnemucca, Nevada, 200 miles (320 km) to the east.[4] Together these events created the Devastated Area which is still sparsely populated by trees due to the low nutrient and high porosity of the soil there.

Later volcanic activity

For several years after the May 22, 1915, eruption, spring snowmelt percolating down into Mount Lassen triggered steam explosions, an indication that rocks beneath the volcano’s surface remained hot. Particularly vigorous steam explosions in May 1917 blasted out the second of the two craters now seen near the northwest corner of the volcano’s summit (two older craters are buried).[4]

Steam vents could be found in the area of these craters into the 1950s but gradually waned and are difficult to locate today. Since then, the USGS in cooperation with the United States Park Service have been monitoring Lassen and other volcanic and geothermal areas in the park.

See also

- High Cascades

- Geology of the Pacific Northwest

- Lassen Volcanic National Park

- Volcanic Legacy Scenic Byway

- List of highest points in California by county

References

Major works cited

- Geology of National Parks: Fifth Edition, Ann G. Harris, Esther Tuttle, Sherwood D., Tuttle (Iowa, Kendall/Hunt Publishing; 1997) ISBN 0-7872-5353-7

- EO Newsroom (NASA), New Images of Lassen Volcanic National Park (adapted public domain text; Retrieved 18 September 2006)

- Eruptions of Lassen Peak, California, 1914 to 1917, U.S. Geological Survey Fact Sheet 173-98 (adapted public domain text; Retrieved 18 September 2006)

Notes

- ↑ The elevation of this summit has been converted from its National Geodetic Vertical Datum of 1929 (NGVD 29) elevation of 10,457 feet (3,187 m) to the North American Vertical Datum of 1988 (NAVD 88) elevation of 10,462 feet (3,189 m). National Geodetic Survey

- ↑ 2.0 2.1 2.2 "AMERICA'S 57 - THE ULTRAS". Peaklist.org. Retrieved on 2008-09-28.

- ↑ USGS GNIS: Lassen Peak

- ↑ 4.00 4.01 4.02 4.03 4.04 4.05 4.06 4.07 4.08 4.09 4.10 4.11 4.12 USGS: Eruptions of Lassen Peak, California, 1914 to 1917

- ↑ Ski Mountaineer

- ↑ Glaciers of California, glaciers.pdx.edu (accessed 4 January 2008)

- ↑ EO Newsroom

External links

- The Official Lassen Volcanic National Park Web Site

- USGS: Eruptions of Lassen Peak, California, 1914 to 1917

|

||||||||||||||||