Larynx

| Larynx | |

|---|---|

|

|

| Anatomy of the larynx, anterolateral view | |

|

|

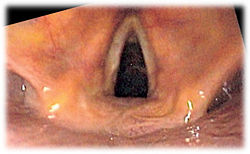

| Endoscopic image of larynx |

The larynx (plural larynges), colloquially known as the voicebox, is an organ in the neck of mammals involved in protection of the trachea and sound production. The larynx houses the vocal folds, and is situated just below where the tract of the pharynx splits into the trachea and the esophagus.

Contents |

Function

Sound is generated in the larynx, and that is where pitch and volume are manipulated. The strength of expiration from the lungs also contributes to loudness, and is necessary for the vocal folds to produce speech [1].

Fine manipulation of the larynx is used in a great way to generate a source sound with a particular fundamental frequency, or pitch. This source sound is altered as it travels through the vocal tract, configured differently based on the position of the tongue, lips, mouth, and pharynx. The process of altering a source sound as it passes through the filter of the vocal tract creates the many different vowel and consonant sounds of the world's languages.

During swallowing, the backward motion of the tongue forces the epiglottis over the laryngeal opening to prevent swallowed material from entering the lungs; the larynx is also pulled upwards to assist this process. Stimulation of the larynx by ingested matter produces a strong cough reflex to protect the lungs.

The vocal folds can be held close together (by adducting the arytenoid cartilages), so that they vibrate (see phonation). The muscles attached to the arytenoid cartilages control the degree of opening. Vocal fold length and tension can be controlled by rocking the thyroid cartilage forward and backward on the cricoid cartilage, and by manipulating the tension of the muscles within the vocal folds. This causes the pitch produced during phonation to rise or fall. In most males the vocal cords are longer, producing a deeper pitch.

The vocal apparatus consists of two pairs of mucosal folds. These folds are false vocal cords (vestibular folds) and true vocal cords (folds). The false vocal cords are covered by respiratory epithelium, while the true vocal cords are covered by stratified squamous epithelium. The false vocal cords are not responsible for sound production, but rather for resonance. These false vocal cords do not contain muscle, while the true vocal cords do have skeletal muscle.

Innervation

The larynx is innervated by branches of the vagus nerve (CN X) on one side. Sensory innervation to the glottis and supraglottis is by the internal branch of the superior laryngeal nerve. The external branch of the superior laryngeal nerve innervates the cricothyroid muscle. Motor innervation to all other muscles of the larynx and sensory innervation to the subglottis is by the recurrent laryngeal nerve.

Injury to the external laryngeal nerve causes weakened phonation because the vocal cords cannot be tightened. Injury to one of the recurrent laryngeal nerves produces hoarseness, if both are damaged the voice is completely lost and breathing becomes difficult.

Muscles associated with the larynx

- Cricothyroid muscle lengthens and stretches the vocal cords.

- Posterior cricoarytenoid muscle abducts the vocal cords.

- Lateral cricoarytenoid muscle adducts the vocal cords.

- Thyroarytenoid muscle (also called vocalis muscle) shortens vocal cords.

- Transverse arytenoid muscle adducts the vocal folds.

Notably, the only muscle capable of separating the vocal cords for normal breathing is the posterior cricoarytenoid. If this muscle is incapacitated on both sides, the inability to pull the vocal cords apart (abduct) will cause difficulty breathing. Bilateral injury to the recurrent laryngeal nerve would cause this condition. It is also worth noting that all muscles are innervated by the recurrent laryngeal branch of the vagus except the cricothyroid muscle, which is innervated by the external laryngeal branch of the vagus.

Descended larynx

In most animals, including infant humans and apes, the larynx is situated very high in the throat — a position that allows it to couple more easily with the nasal passages, so that breathing and eating are not done with the same apparatus. However, some aquatic mammals, large deer, and adult humans have descended larynges. An adult human, unlike apes, cannot raise the larynx enough to directly couple it to the nasal passage. Proponents of the Aquatic ape hypothesis claim that the similarity between the descended larynx in humans and aquatic mammals further supports their theory[2].

Some linguists have suggested that the descended larynx, by extending the length of the vocal tract and thereby increasing the variety of sounds humans could produce, was a critical element in the development of speech and language. Others cite the presence of descended larynges in non-linguistic animals, as well as the ubiquity of nonverbal communication and language among humans, as counterevidence against this claim.

Disorders of the larynx

There are several things that can cause a larynx to not function properly. Some symptoms are hoarseness, loss of voice, pain in the throat or ears, and breathing difficulties.

- Acute laryngitis is the sudden inflammation and swelling of the larynx. It is caused by the common cold or by excessive shouting. It is not serious. Chronic laryngitis is caused by smoking, dust, frequent yelling, or prolonged exposure to polluted air. It is much more serious than acute laryngitis.

- Presbylarynx is a condition in which age-related atrophy of the soft tissues of the larynx results in weak voice and restricted vocal range and stamina. Bowing of the anterior portion of the vocal cords is found on laryngoscopy.

- Ulcers may be caused by the prolonged presence of an endotracheal tube.

- Polyps and nodules are small bumps on the vocal cords caused by prolonged exposure to cigarette smoke and vocal overuse, respectively.

- Two related types of cancer of the larynx, namely squamous cell carcinoma and verrucous carcinoma, are strongly associated with repeated exposure to cigarette smoke and alcohol.

- Vocal cord paresis is weakness of one or both vocal folds that can greatly impact daily life.

- Idiopathic larangyal spasm

- Laryngomalacia is a very common condition of infancy, in which the soft, immature cartilage of the upper larynx collapses inward during inhalation, causing airway obstruction.

- The world's first successful larynx transplant took place in 1999 at the Cleveland Clinic. [3]

Cartilages

There are six in all, three unpaired and three paired.The cartilages of the larynx are the thyroid, cricoid, epiglottis, arytenoids, corniculate, and the cuneiforms.

Images

See also

- Laryngitis

- Epiglottitis

- Intubation

- Phonation

- Voice organ

- Phonetics

- Vocology

- Acoustic phonetics

- Mechanical larynx

|

||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

References

- ↑ Titze, I.R. (1994). Principles of Voice Production, Prentice Hall, ISBN 978-0137178933.

- ↑ Morgan, Elaine (1997). The Aquatic Ape Hypothesis. Souvenir Press Ltd. ISBN 0 285 63518 2.

- ↑ University Circle Inc

Speech and Hearing Science: Anatomy and Physiology 3rd edition. Willard R. Zemlin. 1988. Prentice-Hall, Inc. Englewood Cliffs, New Jersey. ISBN 0-13-827429-0